Greenwood-I_Read_It - California State University, Northridge

advertisement

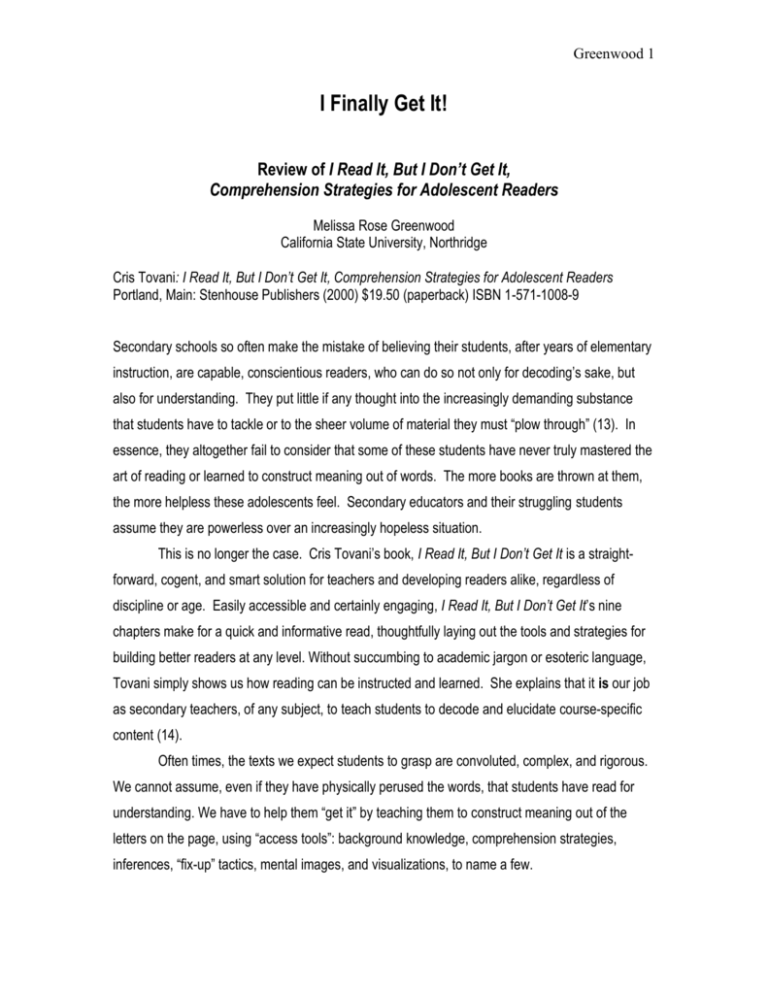

Greenwood 1 I Finally Get It! Review of I Read It, But I Don’t Get It, Comprehension Strategies for Adolescent Readers Melissa Rose Greenwood California State University, Northridge Cris Tovani: I Read It, But I Don’t Get It, Comprehension Strategies for Adolescent Readers Portland, Main: Stenhouse Publishers (2000) $19.50 (paperback) ISBN 1-571-1008-9 Secondary schools so often make the mistake of believing their students, after years of elementary instruction, are capable, conscientious readers, who can do so not only for decoding’s sake, but also for understanding. They put little if any thought into the increasingly demanding substance that students have to tackle or to the sheer volume of material they must “plow through” (13). In essence, they altogether fail to consider that some of these students have never truly mastered the art of reading or learned to construct meaning out of words. The more books are thrown at them, the more helpless these adolescents feel. Secondary educators and their struggling students assume they are powerless over an increasingly hopeless situation. This is no longer the case. Cris Tovani’s book, I Read It, But I Don’t Get It is a straightforward, cogent, and smart solution for teachers and developing readers alike, regardless of discipline or age. Easily accessible and certainly engaging, I Read It, But I Don’t Get It’s nine chapters make for a quick and informative read, thoughtfully laying out the tools and strategies for building better readers at any level. Without succumbing to academic jargon or esoteric language, Tovani simply shows us how reading can be instructed and learned. She explains that it is our job as secondary teachers, of any subject, to teach students to decode and elucidate course-specific content (14). Often times, the texts we expect students to grasp are convoluted, complex, and rigorous. We cannot assume, even if they have physically perused the words, that students have read for understanding. We have to help them “get it” by teaching them to construct meaning out of the letters on the page, using “access tools”: background knowledge, comprehension strategies, inferences, “fix-up” tactics, mental images, and visualizations, to name a few. Greenwood 2 According to Tovani, reading instruction at the secondary level must reflect the rigors of the material, moving away from sophomoric decoding toward meaning uncovery, a more advanced skill. Modeling how we, as skilled readers, access and unearth meaning is one excellent way to help adolescents learn this skill. “Think about what you as a good reader do to construct meaning and model it for your students,” Tovani suggests (21). But don’t assign material that’s so difficult it is inaccessible for students. This, according to Tovani, is a waste of time (19). We educators need to prepare ourselves to re-teach the fundamentals that students can access before we require texts that are beyond their reach, all the while teaching them advanced strategies to help them eventually tackle more complex materials on their own. One of Tovani’s favorite strategies for helping students to unveil meaning is thinking out loud, what researchers Pearson et. al (1992) dub “mental modeling” (26). Tovani recommends stopping often to think out loud for students to describe what is going on in your own head and to verbally demonstrate the comprehension strategies you, the teacher, use to construct meaning when you are stuck (27). Students may be surprised to learn that even their instructors are not above struggling through a text. When they see that we don’t simply give up when we are confused, they will be more inclined to stick with a text the next time they are puzzled, fighting to gain understanding rather than shutting their books in frustration. This modeling strategy is especially effective if students can see, with visual aids, what they hear us reading. We can make these aids available by putting a text up on a transparency or by providing students with hard copies of their own to mark up and annotate, which “gives them a way to stay engaged in their reading…[and to] remember what they were thinking when they read (29, 87). Ultimately, what thinking out loud does is help “to take away some of the comprehension guess work they [students] encounter” at the secondary level, when reading becomes increasingly difficult and even convoluted (28). Often, Tovani says, when an activity fails, it is because the teacher has not done enough modeling to “give students words and examples to frame their thinking” (82). Tovani’s double entry diary is an easy and effective tool to implement in the classroom, by forcing students to infer meaning directly from the text, an essential school and life skill. Folding a piece of paper in half, lengthwise, students can write quotations on one side of the page and their thoughts on the other, using phrases such as “this reminds me of,” “I wonder,” and “this means” to focus their understanding. This is a strategy they so need to master in the world of academic writing. How nice that we can collectively aid our comprehension as readers by doing Greenwood 3 the very thing we have always done to gain understanding and generate ideas—write. Tovani puts it succinctly: “writing down [thoughts]…allows readers to clarify their thinking” (53). Another of Tovani’s simple strategies geared at improving comprehension is a highlighting activity. She gives students two different colored highlighters, instructing them to highlight everything they‘ve understood in one color and everything they haven’t in another. This easy to implement tool makes students directly responsible for their own learning as well as resources for their peers, both of which are empowering. Each student must identify his/her confusion (half the battle), and gain clarity through peer tutorials, at the same time as he/she helps other students repair meaning. This tool and others are interdisciplinary—they are accessible to diverse content areas: science, history, drama, etc. No matter the subject, they help to aid student comprehension. Tovani urges teachers in every discipline to take responsibility for teaching student reading, as it is not a task to be tackled by English professionals alone, but one in which students arguably need explicit, specialized instruction. “It is vital that students make connections when they read. It is up to teachers [of all disciplines] to show them how…middle and high school teachers can and must teach students to be better readers of their [specific] course material (64, 14). It is no more reasonable to expect English teachers to help students access their science books than it is to ask math teachers to help students understand their history books. Each content area is replete with subject-specific jargon and thus, must include subject-specific reading instruction. One way to engage students and improve their comprehension is by providing them with ample background knowledge: “a repository of memories, experiences, and facts [which help them to]…assimilate new information” (64). Again, this information is field-specific and should, according to Tovani, be taught in all subject areas. Forcing students to leap into a text without any information is like asking them to walk a tightrope, blind—unreasonable and hazardous at best. If we teachers expect students to succeed, we must not only provide them with background information, but also elicit the personal knowledge and experience they already bring with them to the table. Facilitating student questions and connections are two additional tools Tovani advocates in her book. Texts are not meant to be read and understood in a bubble. Quite the contrary—they are meant to be relevant to ourselves, to the world, and to other texts (69). Making connections allows readers to relate to characters, visualize scenes, avoid boredom, pay attention, listen to Greenwood 4 others, and read actively (73). It also greatly improves understanding, especially when modeled by the teacher. Students understand a story better when they have heard it read from another perspective (75). By first showing students how to make connections to the text, we give them the tools to next do it on their own. They need this guided practice or scaffolding before they can be expected to perform without help (89). Finally, when we model questioning, we require our students “to think and actively engage in the reading” (92). They begin to learn that often times, the “answers” are found in their own minds, and not necessarily supplied by words in the texts alone (93). This is not to say that any unsubstantiated answer is correct (readers still need “evidence from the text to support their thinking”), but rather that probing and analysis are necessary tools for enhancing reading comprehension. In essence, “the reader is forced to go beyond the words to find the answer” (53). Again, as teachers it is our responsibility to “renew…students’ curiosity and guide them toward inquiry,” especially when presenting them with “difficult or uninteresting material” (93, 85). By providing concrete examples and strategies that she herself has successfully employed in the classroom, Tovani, a reading expert, provides fellow teachers of all disciplines with a valuable gift—tools to enhance student reading comprehension at any level. She diverts responsibility to us, the instructors, and entrusts us to disseminate, demystify, and illuminate course-specific content for our students, lest they give up on reading entirely. I Read It, But I Don’t Get It is a must read for any educator who cares about student success.