national qualifications curriculum support

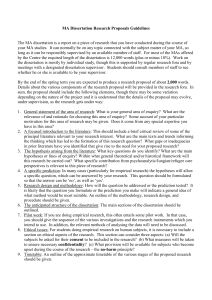

advertisement

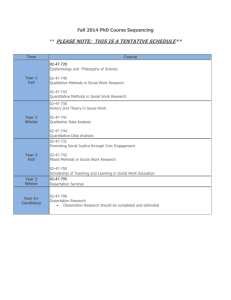

NAT IONAL QUALIFICAT IONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT History Student Guide to Historical Research, Dissertation Writing and Assessment [ADVANCED HIGHER] Elizabeth Trueland Acknowledgements This document is produced by Learning and Teaching Scotland as part of the National Qualifications support programme for History. First published 2002 Electronic version 2002 © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2002 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educati onal purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. ISBN 1 85955 916 6 CONTENTS Introduction iv Section 1: The Historical Research unit 1 Section 2: Getting started on the research 3 Section 3: Reading and note maki ng 7 Section 4: Writing the dissertation 11 Section 5: Bibliography 17 Appendi x: Student guide to assessment 19 HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) iii INTRODUCTION Introduction This student guide aims to provide practical suggestions about how to tackle the Historical Research unit for Advanced Higher History. It takes students through the processes involved in planning, researching and preparing a major piece of historical writing. It shows how these stages will enable students to meet the two Outcomes identifie d for Historical Research as part of the ongoing process of working on their dissertation. It also tackles some of the issues involved in writing the dissertation that is assessed externally as part of the National Qualification in Advanced Higher History. It is hoped that this guide will be of use to all students working on Advanced Higher History Historical Research, whatever their chosen field of study. The Appendix The Appendix contains information handed out to S6 students in one school that presented a number of candidates for Advanced Higher History in the first year of the examination. The information therefore reflects the particular circumstances of that school and it is included here as exemplars of the sort of material that may prove helpf ul to students who are taking the Advanced Higher course. Similarly, the syllabus outlines are one History Department’s approach to teaching and learning in Field of Study 10, South Africa 1910 –1984. They represent an attempt to flesh out the course and to provide a range of focused topics for study/discussion, while ensuring good coverage of all of the main themes of the course. It should be stressed, however, that this is simply one possible approach and that there are many other ways of teaching this topic. iv HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) TH E H I S TO R I CA L R E S EA RCH U NI T SECTION 1 The Historical Research unit Historical Research is a 40-hour unit that forms part of the National Qualification in Advanced Higher History. You research, plan and prepare a dissertation on an issue relevant to your chosen field of study. The process of researching, planning and preparing the dissertation is assessed internally. Your completed dissertation will be submitted to SQA for external assessment, together with an annotated bibliography, which will be taken into account in the assessment of the dissertation. The dissertation is worth 50 marks out of a total of 140 in the external assessment. It should be no more than 4,000 words long, excluding footnotes. If the dissertation exceeds 4,000 words, up to 10% of the available marks can be deducted. Choosing an issue to research You should start thinking about your choice of issue at the very beginning of the Advanced Higher course. Your teacher will give you a list produced by SQA of possible dissertation issues from which you can choose one that interests you. Alternatively, you may wish to research an issue that is not included on the SQA list. It may be that you have already done some background reading that has raised significant questions about an aspect of your chosen field of study, or your teacher may be aware of interesting resources, available locally, that would facilitate the study of a particular, worthwhile issue. If you do choose an issue that is not included on the SQA list, it is very important that your alternative choice of issue should be submitted to the SQA for approval by 1 October of the academic year in which you are completing the Historical Research unit. This is to ensure that your choice of topic is realistic and that it is in accordance with th e requirements of the Advanced Higher course. Whether you choose an issue from the relevant SQA list of topics, or submit your own choice of issue for approval, it is important that you choose an issue that interests you and about which you wish to understand more. A good issue gives rise to further challenging questions that may involve controversy, or be open to more than one HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 1 TH E H I S TO R I CA L R E S EA RCH U NI T interpretation. A good issue should lead you into analysis rather than narrative. If you have some prior knowledge of your chosen field of study (perhaps from your Higher History course, or from your own reading), you might already have some ideas about what particular issues will involve. However, if your chosen field of study is not familiar to you, you will need to do some basic fact-finding research before you can make an informed decision about your choice of issue. This might take the form of reading a short, general overview history of the whole field of study. For some topics, books written primarily as school textbooks could provide a suitable introduction. It might also be possible to view a video that provides an introduction to some of the issues raised by the field of study. For some fields of study, there might also be useful CD Roms or websites that provide background information to give you an idea about what is involved. Biographical dictionaries and encyclopaedias are also worth consulting at this stage. Discuss possible issues with your teacher/lecturer. S/he may be able to give advice about the availability of resources that might affect your final decision. Having chosen your issue, you are required to explain how it relates to the field of study as a whole. In other words, you need to place the chosen issue in its historical context (Outcome 1 PC (a)). This can be done in a few sentences. It is enough to show that you understand how the detailed aspect of the field of study you have chosen relates to the overall period which you are studying. You might already be aware of controversies arising out of the issue, in which case these can be mentioned in the statement, although this is not a requirement at this early stage in your wor k. 2 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) G E T T IN G S T AR T E D O N T H E RE S E AR CH SECTION 2 Getting started on the research Initial brainstorming Having decided on your issue, you need to co nsider how you will carry out your research. Even if your knowledge of your chosen issue is limited, it is a good idea at this stage to put down on paper some of the questions that you think you should consider. You might subsequently reject some of the id eas that you include in this initial brainstorming, and you will certainly add others of which you are not already aware. Nevertheless, brainstorming helps to give your work an initial focus. Mind mapping is one way of brainstorming. This is how an initi al mind map might look (for a dissertation relating to the black contribution to the American Civil War – Field of Study 7): Historiography: recent views of black/white military historians Romanticised, Hollywood view Impact of the emancipation proclamation How important was the contribution of black soldiers in the US Civil War? Racist attitudes towards blacks in Union army Contribution to Union war effort Treatment of blacks in the Union army Treatment of black soldiers by the Confederate armies Factors limiting impact of black soldiers Revisit these ideas frequently. Above all, be prepared to amend them in the future! Selecting resources You should also make a list of the sources of information that you intend to use when researching your dissertation. These should include primary as well as secondary sources. HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 3 G E T T IN G S T AR T E D O N T H E RE S E AR CH In most cases your main sources of information will be books and articles published in historical journals. However, some of the following might also be of relevance: site visits artefacts maps newspapers websites art galleries The relevant Advanced Higher annotated bibliography is a good starting point. This helps identify the key works that you should consult. Some of these will be in the departmental or school/college lib rary. Others will be less accessible and you will need to consider how you will be able to consult them. Forward planning is important; you are unlikely to be able to obtain at short notice a book that is not in the school/college library. Given sufficien t notice, however, the school/college librarian might be able to obtain a specific title for you through inter -library loans, although this can take several months – so plan ahead! If you are fortunate enough to have access to a university library, you will be able to go there to consult many of the books that you need. Most university library catalogues can now be consulted on-line, so you can find out: • whether the library has a copy of the book you require • whether it is available for consultation. In some cases, the Advanced Higher bibliography will only provide a starting point. You should also consult the bibliographies provided in recent textbooks on the period/topic that you are researching. Footnotes can also provide useful further references. Your choice of issue could mean that there are relatively few specialist studies directly relevant to your chosen topic. In other cases, however, you will find that there are enormous numbers of published works, and you will have to be selective about what you consult. After all, it is said that there have been well over 50,000 works published on the American Civil War! As a general rule: • Use recently published books in preference to older ones, unless you know that a particular older title is historiographically important, or will provide information or analysis not available in later works. 4 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) G E T T IN G S T AR T E D O N T H E RE S E AR CH • Use texts written by academic (i.e. university) historians, rather than books written by non-specialists. An academic historian is likely to base what s/he writes on his or her own recent research. Often either the cover, or the preface, will provide important information about the author of a book. (Note that many high quality textbooks for school students are written by non-specialists. You should treat these as a good starting point, but do not expect such non-specialist books to entirely replace books by academic historians.) • Consult primary as well as secondary sources of information. The range and availability of primary sources will depend on your f ield of study. For Field of Study 1 (Northern Britain from the Romans to AD1000), fieldwork observations and the analysis of archaeological evidence are likely to be relevant. • Where possible, identify the historian’s viewpoint. Again, the Advanced Higher annotated bibliography should be helpful here. You should also consult the Advanced Higher guide to historiography. A Marxist view of the past will be very different from that of a right -wing historian. Always discuss your proposed reading with your teacher/lecturer. S/he may want to suggest additional, or alternative, titles that you should consult. S/he may also be able to help you with regard to the availability of particular resources in your area. Remember that you should make a list of the p rimary and secondary sources you have consulted, and that you should be able to comment on the relevance of each to your dissertation topic. Make a note of the title of each book you have consulted, the name of the author and the date and place of publicat ion. This will enable you to show you have met Outcome 1 PC(b), ‘information is sought from a range of primary and secondary sources’. HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 5 6 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) RE AD I N G AN D NO T E M AK IN G SECTION 3 Reading and note making This will be a major part of your work for your dissertation. It is also the aspect of your work that is most personal, in that the notes you make are meant to help you remember key pieces of relevant information and important analysis. They are not meant to be a shortened version of a whole book! Notes that are too brief will not help you when you come to write your dissertation. On the other hand, notes that are too detailed will not help you recognise the main points in an author’s argument. Too much detail will also mean that your research becomes too lengthy and time-consuming a process. There is no single ‘right’ way of note making. However, the following should provide useful guidance: • For any book that you are consulting, always note down the title of the book, the name of the author and the date and place of publica tion. • Make a brief note of factual evidence that is relevant to your chosen topic. • Note down statements of opinion. You should identify opinion by using terms such as ‘According to Davenport …’ or ‘In Kershaw’s opinion …’. • Try to read a section of the book through before starting to make notes. A section might be a whole chapter, or just part of a chapter. Then, if you think that the information or the argument is relevant to your dissertation, go back and summarise the main points while they are still fresh in your mind. • Remember that you do not have to make notes on everything you read! It is also important that you should learn to rely on your memory and your growing understanding of a particular issue. • If you come across a reference to differences between professional historians, note down the names of those involved in the debate, and a summary of what each has argued. HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 7 RE AD I N G AN D NO T E M AK IN G Your teacher/lecturer may ask to see your notes as part of her/his assessment of Outcome 1 PC(c ) – ‘relevant information is selected from the sources’. Planning the dissertation Although the initial ‘brainstorming’ should have given you some ideas about what you hope to consider in your dissertation, as you read around the topic you will have a clearer idea of the issues that are involved. You must be willing to amend your initial plan in the light of your research. You should also be prepared to discuss your ideas with your teacher who might suggest other aspects of the topic that could be important. You might reali se that your initial plan covers too much and decide to focus on those aspects of the issue which emerge from your reading as being the most significant. Once you have done sufficient reading to be able to make a confident start on your dissertation, you should draw up a clear plan, outlining how you intend to approach your chosen issue. • You will need to have a clear introduction that sets the issue in its historical context and identifies the approach that you intend to take. • It is recommended that you divide your work into chapters, or sections, with each chapter/section examining one aspect of the topic. • Obviously you will also need a conclusion that draws together your findings and provides your researched, analytical answer to the issue y ou have been considering. It is suggested that your plan should be about 150–200 words in length. Where appropriate, it should include references to the views of different historians. It is also important that you analyse the evidence available to you a nd reach an informed judgement about the issue. Planning your dissertation in this way will ensure that you produce a structured, well argued dissertation. It will also help your teacher to provide you with advice at this stage since the approach that yo u intend to take should be clearly identifiable from your plan. 8 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) RE AD I N G AN D NO T E M AK IN G Example 1 Issue: Why did the Reds win the Civil War? (Field of Study 11: Soviet Russia 1917–1953). A good plan might include the following: Introduction: The background to the Civil War in Russia (setting the issue in its historical context) and the uncertainty about the outcome. The range of possible reasons why the Bolsheviks finally won; outline of the approach to be taken in the dissertation, with reference to possible historical d ebate regarding the significance of particular factors. Chapter 1: An analysis of the role of Trotsky and of the Red Army. Chapter 2: An assessment of the contribution War Communism made to the Bolsheviks’ ultimate victory in the Civil War. Chapter 3: An assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the Bolsheviks’ opponents: the White armies and the failure of foreign intervention. Historians’ views should be included in each of these chapters. Conclusion: An assessment of the relative importance of all of these factors, providing a clear answer to the question raised in the dissertation title. Example 2 Issue: Military defeat or a failure of southern nationalism? An examination of the reasons why the South lost the Civil War. (Field of St udy 7: The House Divided: The USA 1850–1865) N.B. this is an example of a promising dissertation title that is not included in the list of dissertation issues and which would therefore have to be submitted to SQA before 1 October. A good plan might include the following: Introduction: Early Civil War historians considered Northern victory inevitable; more recently historians have questioned why Lee’s surrender at Appomattox ended all Southern resistance. Outline of the range of possible explanations. HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 9 RE AD I N G AN D NO T E M AK IN G Section 1: Southern nationalism; initial support in the South for secession; the traditional emphasis on states’ rights and the extent to which this undermined a sense of Southern nationalism; the contribution of individual Southern politicians who put state rights ahead of centralised power and the war effort. Section 2: Military defeat: military turning points in the war; the impact of the Union campaigns of 1864; the reasons why the South was not able to continue traditional warfare by 1865. Section 3: Economic factors: an evaluation of the economic consequences of the war for the South. Section 4: Why was the South fighting? The lack of a single, unifying war aim in the South. Section 5: The loss of the will to fight; the extent to which los s of will may have been the critical factor in the failure of the Southern war effort. Conclusion: The historical debate regarding the reasons for Southern defeat in the Civil War. Military defeat led to a loss of will to fight; Southern nationalism was not sufficiently strong to revive flagging support for military resistance. Your written plan should meet the requirements of Outcome 2 PC(c). In discussing your approach with your teacher, and by showing awareness of the main issues involved, you should be able to meet Outcome 2 PC(a) and PC(b). 10 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N SECTION 4 Writing the dissertation Once you are ready to start writing, you should aim to produce a first draft of your dissertation, so that your teacher can provide you with feedback about possible omissions, areas that need greater clarification, etc. You may then amend your dissertation, in the light of these comments. This will provide you with a further important opportunity to discuss your chosen issue with your teacher. The introduction The introduction is a very important part of the dissertation. A good introduction sets the topic in its historical context, identifies some of the significant historical issues that are involved and clarifies the approach that will be taken. Two examples of very good introductions are given below. Example 1: Field of Study 10: South Africa 1910 –1984 Dissertation title: The development of Afrikaner nationalism to 1948: preservation, adaptation and propagation of the Afrikaner sense of identity. ‘Ask the nation to lose itself in some other existing or as yet non-existing nation, and it will answer: by God’s honour, never.’ (D F Malan, 1915) If the notion of an Afrikaner nation was very tangible to Afrikaners following the Nationalist victory in the 1948 election, the mere concept of Afrikanerdom, or even of an Afrikaner, had been uncertain fifty years earlier. It was in this period that the Afrikaner identity was moulded into its modern form, a counterforce first against British Imperialism, then against Marxism. Once in power, the Nationalists remained as the only real force in South African politics until 1990, surviving international condemnation and staving off the threat of black majority rule. The development of Afrikaner nationalism before 1948 was, therefore, of vital importance. How did the Afrikaners come to identify themselves as such a HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 11 WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N distinct group? The first section of this dissertation will concentrate on the role of language, religion and history in the Afrikaner identity and how these came together to form one coherent ideology. The second section will focus on how this identity 12 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N was propagated and how it permeated society – the role of cultural and economic organisations in the creation and safeguarding of the volk. Finally, any attempt to measure the success of Afrikaner nationalism has to take account of its political impact, in the years preceding the election victory of 1948. (230 words) Example 2: Field of Study 9: Germany: Versailles to the Outbreak of World War II) Dissertation title: A State within a State: who controlled the SS – Hitler or Himmler? Created in 1923, the SS (or Schutzstaffel – protection squads ) was only three hundred strong when Himmler was appointed Reichsführer-SS in 1929, but it grew into a huge organis ation that encompassed so many roles that it has been described as a ‘State within a State’. The SS would mastermind and implement the liquidation of the Jews, create a financial empire, and grow into an armed force that would rival the Wehrmacht. Clearly this touches on some historiographical issues: namely the question of who was responsible for the Holocaust, the intentionalist–structuralist debate, and the nature of Hitler’s rule. The issue of the responsibility for the Holocaust is currently the most controversial. There is a wide variety of opinions which could lead to the conclusion that it was solely the SS, headed by Himmler, that was responsible for the Holocaust, and hence in this respect the SS was truly a ‘state within a state’, or that the SS were the professionals employed for the task by a collectively eager German nation. It seems to me that the role of Hitler requires examination in conjunction with both opinions. The issue is closely linked to the debate on the nature of Hitler’s rule. As Kershaw comments, today ‘historians are in no fundamental disagreement over the fact that the government of Nazi Germany was chaotic in structure’. Himmler’s ‘massive HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 13 WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N coercion of power’ is evidence of the disorganised nature of the state, as well as the squabbles between the second tier of ruling Nazis, who tried to outdo each other in influence and power. In this dissertation, I intend to examine the three areas in which I consider the possibility of the SS being a real ‘State within a State’ was the most likely: the final Solution, the financing of the organisation, and the role of the Waffen -SS. I will also examine who actually controlled the SS – Hitler or Himmler. (317 words) (In both examples, footnote references have been omitted.) 14 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N In the two examples given above, a sound introduction ensures that the structure of the dissertation is clear from the start. It is also evident that the candidate’s approach will involve argument based on evaluation and analysis of evidence. Questions have been identified that have to be addressed in the main part of the dissertation and it is clear that the conclusion will have to attempt to provide answers to the issues raised. The main chapters/sections of the dissertation Whether or not you decide to divide your dissertation into separate chapters, your plan should ensure that the main body of your dissertation has a clear structure and that what you write is clearly relevant to your chosen issue. You should avoid a largely narrative approach (in other words, you should not be ‘telling the story’). Factual evidence must be used to argue a particular point of view. In the following brief extract, a candidate is examining the view that the Provisional Government, established in Russia in February 1917, h ad little credibility from the start. It provides a very good example of using evidence to construct a historical argument. (The extract relates to Field of Study 11: Soviet Russia 1917 –1953) The abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and his brother’s subsequen t refusal to accept the throne created a power vacuum in Russia which the Provisional Government duly announced it would fill. Those critical of the Provisional Government would perhaps say that they should have realised that they were doomed from the outset when a bystander in the crowd responded to the announcement of the Provisional Government’s establishment by demanding: ‘And who appointed you?’ The fundamental reason for such a statement is that the Provisional Government really had no legitimacy to take power. Their only real electoral mandate was in the Duma, a watered down remnant of the overthrown regime. An indicator of exactly how unrepresentative the Provisional Government was of the political affiliations of the Russian people came from the l ocal elections later in the year. The Kadets, the major influence in the Provisional Government, performed disastrously. This highlighted the unlikelihood of the Provisional Government ever truly representing the interests of the majority of Russians. HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 15 WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N The Provisional Government also experienced difficulties in their relationship with the Petrograd Soviet. This institution, which was the safeguard of the rights of workers and soldiers of Russia, entered into a relationship with government 16 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N known as ‘Dual Power’. However, there is little argument among historians that entering into this relationship and allowing it the almost total control it gained from Soviet Order No. 1 was one of the most monumental of the Provisional Government’s many mistakes. The Petrograd Soviet fooled and betrayed them. Although its relationship with the Petrograd Soviet exposed it as weak and ineffective in the eyes of the people, the Provisional Government’s failure to produce solutions for the key issues of 1917 and their apparent lack of commitment to these issues further jeopardised the nation’s confidence. They staked their entire future on a hope for democracy which would transcend any other hopes the Russian people might have had. The conclusion Every dissertation must have a conclusion in which a considered answer is provided to the issue/s identified in the introduction. The reader should be left in no doubt about what you have made of all the evidence you have considered. Example Issue: Military defeat or a failure of southern nationalism? An examination of the reasons why the South lost the Civil War (Field of Study 9: The House Divided: The USA 1850–1865). Note: the plan of this dissertation was given on pp 9–10. Clearly there is no definitive answer to the complex question of why the South lost the Civil War. Debate still continues and a number of prominent historians have arrived at different conclusions. Did the basic loss of will, caused by a lack of nationalism, bring military defeat to the Confederate s as Beringer, Hattaway, Jones and Still have argued? Or is James M McPherson correct in saying that the loss of will to continue was caused by military events? It was only in 1864, after Sherman’s march had devastated a large area of the South, that desertion rates in the Southern armies soared. Due to military failures, the South was gradually dissected into pieces, towns were destroyed and thousands lost their lives. The HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 17 WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N capturing of the railways, the rivers and the seaports caused the South’s economy to deteriorate rapidly, whilst also making life extremely harsh for Southerners. This undoubtedly weakened Southern morale. The military failures also caused other problems to surface within the Confederacy. Throughout the war years, the importance of s tate rights remained 18 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N high and consequently the South never fully utilised its resources by working together as a nation. The basic lack of a sense of true nationalism caused an unwillingness to carry on a war against other Americans. This constant oppos ition from other parties and pacifists further weakened the South’s war effort. In the North, Lincoln faced a similar problem. However, his military successes weakened his opponents’ cause and helped to win him the support of the public. When the war began to go badly in military terms and life became increasingly difficult, the lack of a real war aim caused many Southerners to question whether the fighting was worth it. As Mary Chesnut wrote in 1864: ‘Think of all the young lives sacrificed. If three for one be killed, what comfort is that? What good will that do?’ Without a nation to fight for, the Southerners lost the will to fight on and it was the loss of will that ultimately led to the collapse of the Confederacy. In the Vietnam War, in the Boer War and in the War of the Triple Alliance in Paraguay, the hardships inflicted on the insurgents were far greater, yet their spirit kept them going. By 1865, the Confederates had had enough. ‘The officers acted in accord with the feelings of their men, the many who had already left the war as well as those who had remained with the colors until the end. And the men reflected the sentiments of the country.’ This loss of will was sparked off by the series of military defeats that had led many Southerners to question their cause. As McPherson concludes, the loss of will theory puts the cart before the horse. Defeat caused demoralisation and loss of will. Therefore Lee’s surrender at Appomattox was precipitated by military failure. Footnotes You are expected to make appropriate use of footnotes in your dissertation. As HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 19 WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N you read, you will notice that many of the books you consult contain numbered footnotes that appear either at the bottom of the page, at the end of the chapter or at the end of the book. Occasionally, these footnotes will contain additional information or comments that add to the main text. Mostly, though, they will refer to another source of evidence (primary or secondary) that has been consulted. You should always provide footnotes for t he following: • direct quotations • specific facts/figures that are central to your argument • analysis that is based on someone else’s argument. 20 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) WR I T IN G T H E D I SS E RT A T IO N Footnotes should be set out in the following way: – Surname and first name or initials of author; Title of book, article, or academic journal; Place and date of publication; Page number(s), i.e. p or pp, where the reference is to several consecutive pages of a book. 1. First reference 2. Consecutive references – Ibid., and the page number (ibid. is short for Latin ibidem, meaning ‘the same source’). 3. Non-consecutive references to the same book and author – surname, op. cit., and the page number. (op. cit. is short for Latin opere citato, meaning ‘in the work cited, or previously quoted’). For example, if you want to refer directly to a point made in The Scottish Nation by Tom Devine you would footnote this in the following way: First reference to the book: Devine, T M, The Scottish Nation 1700–2000, London, 1999, p 25 Consecutive reference to the book: Ibid., p 26 Further reference to Devine’s book, after references to other works: Devine, op. cit. pp 33–4 Important tip! Since you will need to include footnotes in your dissertation, remember to include source and page references in the notes you make as you read. This will save you time in the long run: failure to do this may result in a lot of wasted time later on, looking up an elusive reference. HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY Bibliography As part of your internal assessment you should already have collected full bibliographical details of the resources you have consulted. Therefore, it should not be difficult to compile a bibliography to be submitted with your di ssertation. You should provide details of all of the resources, and collections o f resources, you have consulted. These should include the author’s name, the title of the wor k, the place and date of publication. Where individual pri mar y sources of evidence have been consulted, you should make specific reference to these. HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 23 24 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) S TU D EN T G U ID E TO AS S ES SM E N T APPENDIX Student guide to assessment The AH History course Advanced Higher History consists of two units of work relating to a chosen field of study. These units, which are assessed internally (NAB items) and externally (SQA examination), are: Historical Study (AH) Historical Research (AH) 80 hours 40 hours You will be given a detailed syllabus for the particular field of study that you have chosen. Your work through the year relates to the Historical Study; your work for the dissertation that you will resear ch and write constitutes the Historical Research unit. The number of hours indicated above is suggested as a guide to the number of hours of teaching time; in practice, more class time may be spent on the Historical Study and less on Historical Research. Time spent on homework and personal study is not included in these totals! Internal assessment: Historical Study As there is only one unit covering course content, there is only one NAB item to be completed under ‘test’ conditions. However, this NAB is divided into two parts, reflecting the different Outcomes covered. In practice, the two parts of the NAB may be tackled at different times. In Part 1 of the NAB, you will have one hour in which to write one essay, chosen from up to four essay titles. As in Higher History, you will be expected to write a well informed and well structured essay with a sound introduction and conclusion. In addition you will be expected to show awareness of historiography and different historical interpretations. This is a much more significant aspect of Advanced Higher than it was of Higher History. As at Higher, a mark of 13/25 or more will indicate that you have met the Outcomes and have achieved a pass. If you achieve 15 or above, your answer could be used as evidence of performance at B or A grade for appeal purposes. HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 25 S TU D EN T G U ID E TO AS S ES SM E N T Part 2 of the NAB assesses your ability to evaluate sources. You will be given 1½ hours to answer three questions, from a choice of four. The questions will relate to five sources, at least one of wh ich will be a secondary source. These sources cover the whole period of the field of study. To pass this part of the internal assessment you will need to meet each of the performance criteria (PCs) relating to the two relevant Outcomes. Internal assessment: Historical Research As you work on your dissertation your progress in different aspects of the research will be assessed. You will receive further details about this aspect of internal assessment in due course. External assessment The external assessment of AH History is as follows: The dissertation One 3-hour examination paper Total number of marks available 50 marks 90 marks 140 marks The examination paper is divided into two parts. You are advised to spend 1½ hours on each part. Part 1 consists of six essay questions. You are required to answer two questions (25 marks each). You should spend 45 minutes on each essay. Part 2 consists of three compulsory questions relating to four different sources. Each question is worth 12 marks, but beca use of the weighting given to this part of the examination, the total marks given will be scaled up to a mark out of 40, rather than a mark out of 36. You should spend approximately 30 minutes on each question. 26 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) S TU D EN T G U ID E TO AS S ES SM E N T Department of History Essay section NAB Part 1 SQA examination paper Section A [80-hour unit + 40-hour dissertation] Pass/Fail, based on Outcomes 50 marks 1 essay 1 hour (45 minutes each essay) 2 essays 1½ hours Choice of 4 essay questions Choice of 6 essay questions Document section NAB Part 2 Section B 1½ hours 1½ hours Pass/Fail based on Outcomes [can be marked out of 40] 36 marks 40 marks [weighted 40/140] 3 out of 4 questions must be answered 3 questions 5 sources 4 sources Questions worth 12, 12, 12 and 16 marks Each question worth 12 marks 16-mark question involves evaluation of 3 sources Must include comparison (2 sources) Must meet all the PCs No need to meet all PCs HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 27 S TU D EN T G U ID E TO AS S ES SM E N T Advanced Higher History: Field of Study 10 South Africa 1910–1984 Key issues in South African History Areas of the prescribed syllabus not already covered will be studied through the identified ‘key issues’, during Term II. Identified key issues: • How different were the politics/policies of Smuts and Hertzog? • How significant was Coloured and Indian opposition to the governments of South Africa? • What impact did economic developments have on apartheid and resistance? • What effects did the Homelands policy have on the lives of Black South Africans? • ‘The apartheid state survived for so long lar gely because the international community was so reluctant to challenge it.’ 28 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) S TU D EN T G U ID E TO AS S ES SM E N T Governing South Africa: Advanced Higher History: Field of Study 10: South Africa 1910 –84 Theme Prescribed syllabus covered Identif ied issue(s) 1. Creating the Union of South The 1910 constitutional settlement. 2. White supremacy and segregation 1910 –48 Political developments from 1920 to 1 948: differing approaches of Hertzog and Smuts and the emer gence of the United Part y and t he Nationalists. 3. The growth of Afrikaner nationalism 1910 –48 The Broederbond and t he advance of Afrikanerdom [The emer gence of the Nationalists] The Union of South Africa created to meet Britain’s economic and i mperial interests.’ [Discuss/debate] Was segregation a new development after 1910? ‘Segregation was introduced to meet the needs of capitalism.’ [Debate] [HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DEBATE] ‘Afrikaner nationalism was a carefully for ged movement.’ [Discuss] [HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DEBATE] 4. World War II and its social, economic and political consequences for South Africa 5. The 1948 election [Economic developments; townships; political developments to 1948] Focus f or w ritten w ork/ Assessment Essay on an aspect of segregation Document practice Essay on an aspect of Africaner nationalism Why did the Nationalists win the election of 1948? HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 29 S TU D EN T G U ID E TO AS S ES SM E N T Governing South Africa: Advanced Higher History: Field of Study 10: South Africa 1910 –84 Theme Prescribed syllabus covered Identif ied issue(s) 6. The nature of the apartheid state The creation of the apartheid state 1948 –59 The theoretical basis of apartheid Apartheid policies and their effects 8. Separate development 1959–79 Bantustans and independent Homelands 9. The government response to opposition: (a) The Treason Trial (b) The Police State (c) Total strategy Responses to oppositi on, including: The Treason Trial The Sharpeville Massacre The Rivonia Trial Adaptable policies or a master plan? ‘Safeguarding white supremacy.’ Does this adequately describe the apartheid legislation of 1948–59? ‘The Independent Homelands provided windows of opportunity for some black Africans.’ [Discuss/debate] ‘Total strategy was the rej ection of apartheid in all but name.’ Is this a valid criticism? 7. 30 HI ST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) Focus f or w ritten w ork/ Assessment • Document practice • Document practice S TU D EN T G U ID E TO AS S ES SM E N T Oppressed people in a wealthy land: Advanced Higher History: Field of Study 10 : South Africa 1910 –84 Theme 1. The economy (a) Agriculture and the Land Act of 191 3 (b) The mineral revolution of the 1880s and its 20 t h century consequences (c) The growth of manufacturing Prescribed syllabus covered Economic developments and their consequences, including the white labour force and the strikes of 1913 and 1922, mi grant black wor kers, compounds. 2. Black urban culture Townships 3. The growth of African opposition 4. African opposition to apartheid in the 1950s 5. New for ms of oppositi on to apartheid 1959 -69 6. Soweto (1976) and its impact on resistance t o apartheid Non -white communities and their politics; the founding of the African National Congress Non -white resistance, especially the ANC, including splits in the ANC and the for ming of the PAC. The Sharpeville Massacre; t he for mation of Umkonto wa Si zwa and violence; the Ri vonia trial; the i mprisonment of Nelson Mandela Soweto 1975 Identif ied issue(s) Focus f or w ritten w ork/ Assessment Was the 1913 Land Act as Essay focusing on an harsh as its critics claimed? aspect of economic [HISTORIOGRAPHICAL development DEBATE] [Essay on an aspect ‘The growth of mi ning changed of segregation] African communities f or ever.’ [Discuss/debate] [HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DEBATE] Did black townships create their own culture? • Document practice [HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DEBATE] • Document practice • Document practice HIST O RI C AL RE SE AR CH G UIDE ( AH) 31