Love and Pain and the Teenage Vampire Thing

advertisement

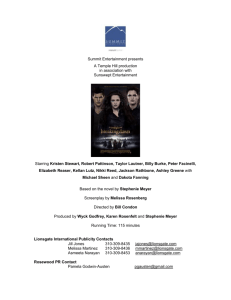

Love and Pain and the Teenage Vampire Thing By TERRENCE RAFFERTY AS the legions of teenagers who have read the novel on which the forthcoming film “Twilight” is based know, the awkward passage from youth to maturity isn’t the very worst problem an adolescent can have. You could fall helplessly in love with a vampire, which is what happens to the virginal 17-year-old heroine and narrator of Stephenie Meyer’s book. “We’ve all had the experience of being that age and feeling that everything is life and death,” said Melissa Rosenberg, who wrote the screenplay. “You know, ‘I have nothing to wear today, I’m going to kill myself.’ What’s so wonderful about this story is that everything actually is life and death.” The transition from page to screen is itself often a less than graceful process, and while it’s rarely a matter of life and death, it can give filmmakers that adolescent sense of unease: “If this movie tanks, I’m going to kill myself.” There’s no denying that in the case of “Twilight” the stakes (so to speak) are high. The four novels in Ms. Meyer’s horror/romance series for young adults — “Twilight” was the first — have sold somewhere near 10 million copies; the most recent, “Breaking Dawn,” racked up sales of 1.3 million on its first day in bookstores in August. And fans are on the rabid side. “There’s all this stuff online,” said the film’s director, Catherine Hardwicke. “People were making casting suggestions, and now they’re doing their own trailers and posters. It’s stimulating, in a way.” A particular hazard with books like Ms. Meyer’s — or like J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels — is that younger readers, unlike their more jaded elders, tend to like their stories just so, with as little variation as possible. And as any adult who has ever read bedtime stories to children understands, when youngsters really go for a story, they’ll insist on hearing it again and again, which is why movies aimed at children, tweens and teenagers can have such a huge payoff for producers and distributors. Two words: repeat business. “I didn’t want to be the screenwriter who disappointed all those readers,” Ms. Rosenberg said. “Nor did Catherine, I’m sure, want to be the director who did so.” Ms. Hardwicke said that when she was approached about directing “Twilight,” she was handed a script that she later realized was “very, very different from the book.” Soon after, “I read the novel myself and I thought, let’s get back to this story, it’s just so much better.” Neither would admit to feeling any constraints on her creativity from the readers’ demands for fidelity to the novel. “My biggest problem was how to condense,” Ms. Rosenberg said. Clearly, the strategy is to swear undying fealty to the book and hope the fans will be merciful. And what, exactly, is this story to which the makers of “Twilight” (opening Nov. 21) have plighted their troth? It’s the tale of a bright girl named Bella Swan who moves to the gloomy town of Forks, Wash., and on her first day at school meets, across a crowded cafeteria, the eyes of a mysterious classmate named Edward Cullen, whom she describes as “devastatingly, inhumanly beautiful.” Edward is a little standoffish, but Bella falls for him hard, while remaining somewhat puzzled by his unteenageboy-like sexual restraint. He’s determined to keep a tight rein on his impulses, which include, in addition to the usual ones, a powerful yen to feed on his new admirer’s blood. When she discovers his secret, she isn’t quite sure how to, you know, feel about this unnerving kink in his personality, but soon decides that being a vampire’s significant other is preferable to depriving herself of this really, really good-looking guy’s company. He remains a perfect gentleman, she a well-behaved lady and their fatal attraction stays (at least in the first novel) unconsummated. Ms. Meyer goes to some trouble to persuade her young readers that there might actually be a Count Charming out there for every shy Bella in the world. The perennially overcast weather of the Pacific Northwest allows Edward to attend school on most days, despite his species’ legendary photosensitivity, and he was raised, as it happens, in a family of “good” vampires, who thoughtfully eschew the consumption of human blood in favor of the nourishing (though less tasty) vital fluids of animals. (They’re kind of the vampire version of vegans.) Edward’s forbearance, however, is sorely tested by the power of his feelings, and Ms. Hardwicke said she believes that the ever-present possibility of Bella’s death actually enhances the story’s romantic appeal. “If ‘Romeo and Juliet’ came out now it would be just as popular,” she said. “Look at ‘Titanic’ a few years ago.” She’s on to something there: the extreme life-and-deathness of the adolescent notion of romance. But the vein that Ms. Meyer’s story taps most obviously is simple, basic fear of sex. Bella is, recognizably, every teenager who is terrified of going all the way, and Edward, less grounded in reality, is a fantasy incarnation of that scared girl’s ideal boyfriend, infinitely — you might say eternally — patient with her trepidation. (And have I mentioned that he’s extremely good-looking?) “The truth,” said the writer Sarah Langan, whose novel “The Missing” won this year’s Bram Stoker Award from the Horror Writers Association, “is that sex can be terrifying at that age, even when you’re in college.” But Ms. Langan, who considers “Twilight” “more romance than horror,” isn’t entirely persuaded by the fear-of-sex model here. “Abstinence is a perfectly valid point of view,” she said. “ ‘Twilight,’ though, struck me as kind of a strange, wrong version of what teenagers are like, especially Edward, who doesn’t even seem to want sex all that much. It made me long for Judy Blume.” The truly peculiar thing about “Twilight,” of course, is that the figure presented here as a paragon of masculine self-control is not, in fact, human and drinks blood. Over the years there have been a fair number of youthful vampires in film and fiction, and some have even been portrayed as objects of desire. The title character of George A. Romero’s “Martin” (1977) probably wouldn’t qualify as anybody’s romantic ideal. But the young lovers in Kathryn Bigelow’s superb 1987 film, “Near Dark,” are tragically cute, as are many of the teenage bloodsuckers in the lame “Lost Boys” (1987), a long-unawaited sequel to which was released last year. There is a broodingly handsome vampire in the lurid new HBO series, “True Blood,” too. “Vampirism is sexy,” Ms. Langan said bluntly. “It’s inherently arousing.” But until “Twilight,” even vampires of the devastatingly, inhumanly beautiful variety did manage, between tragic embraces, to be kind of scary. Angel, the hunky, centuries-old love object of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, would occasionally get a wrinkly, from-hell look on his face, bare his fangs and give vent to the darker side of his nature. At those moments the viewer would fully understand why he was a candidate for what Buffy and her gang referred to as “slayage.” In “Twilight,” slayage isn’t a possibility: the only serious question for Bella and her breathless readers is whether she’ll dare to Do It with her bad-boy lover. Psychologists call this approach/avoidance. And we all might as well figure out a way to approach this strange turn in pop culture, because it looks as if there’s going to be no way to avoid it. The 20 minutes of “Twilight” footage that the studio has made available indicate that the film will be, as Ms. Hardwicke and Ms. Rosenberg promised, exceptionally faithful to its source material. The leads, Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson, look right — there’s a touch of “Titanic”-era Leonardo DiCaprio to Mr. Pattinson — and the mood is appropriately ominous. Describing the shoot in Washington, Ms. Hardwicke said the weather was almost too apocalyptic for her taste. “There was hail,” she said, still shuddering with disbelief. “I bought all this Gore-Tex, and nothing worked.” The whole thing has a slightly funky, no-big-deal air about it, which is perhaps the result of the movie’s relatively modest budget (less than $40 million) and the filmmakers’ modest temperaments. Ms. Hardwicke is best known as the director of youthcentric indie films like “Thirteen” (2003) and “Lords of Dogtown” (2005), while Ms. Rosenberg’s background is mostly in television, as a writer and producer of “Party of Five” and “The O.C.” (More recently, she has worked on the Showtime series “Dexter,” whose characters are grown-ups but which, she said, has something in common with “Twilight” nonetheless: it’s about a “good” serial killer with “internal demons he’s trying to control.”) The movie also appears to capture the oddly timeless atmosphere of the book, in which e-mail notes are sometimes sent but no text messages are, no video games are played, and no one seems to have an iPod crammed with gangsta rap, emo or heavy metal. “You try to keep current with teenagers’ culture and idioms,” Ms. Rosenberg said, “but in ‘Twilight’ some of that feels incongruous. One of the producers actually said to me, ‘I’m uncomfortable when Edward uses a cellphone.’ ” What that means, maybe, is that the world of “Twilight” is one where incoming calls from the real world can rarely be heard with any clarity in a fantasy universe of perpetual neitherhere-nor-thereness. Sort of like adolescence itself, only touched up for maximum (devastating, inhuman) desirability. It’s a place on which the sun never has to set, where the bedtime story never has to end — and that’s what its fans like best about it. Published in the Arts section on November 2, 2008. Trailer: 'Twilight' Copyright 2008 The New York Times Company Children's Privacy Notice