INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTING AND EXCEL

advertisement

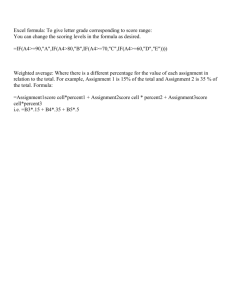

INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTING AND EXCEL Computing in the Sciences. Science is the systematic effort to understand the nature of the physical universe. Scientists have developed powerful tools that are used in this enterprise; the computer is one of these. Computing as a tool is introduced in general chemistry because of its importance in the modern practice of science. An introduction to scientific computing is appropriate as a component of your initiation to science and the scientific method. Scientists use computers in a variety of ways. Computers are required in the control of sophisticated instrumentation and in the acquisition of data. For example, in a typical NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) experiment, a high-power transmitter is turned on and off in ca. 3 s and 4,000 data points are collected in 0.5 s. Computing is invaluable in the manipulation of the massive amount of data generated in the modern laboratory and in the calculation of quantities from first principles. Chemists are now able to calculate the structure of small molecules by solving the Schroedinger wave equation. The scientific literature has grown to the point that several million research articles are published per year. The immensity of the scientific literature was a major driving force behind the development of on-line data bases. Finally, the communication of results discovered in the laboratory is an essential component of the scientific method. Word processing has greatly assisted the preparation of scientific papers and the World Wide Web provides direct access to useful data and the international scientific community. The scope of scientific computing covers the following major categories: control of instrumentation, large-scale numerical calculations (number crunching), data analysis, and communications. A scientist must be familiar with a variety of software as no single software package deals with all of these applications. In general chemistry, we shall focus on data analysis which includes most routine chemical calculations. Data analysis is the most important application of computing in the day-to-day practice of science. Scientists perform a wide range of fairly straightforward calculations; work in a research laboratory is the polar extreme of the assembly line. We have chosen a spreadsheet approach using Microsoft Excel to handle the computation in the General Chemistry laboratory. This document serves as a guide to resources which will enable you to make effective use of spreadsheets and Microsoft Excel. One develops facility with computer applications with practice and this introduction includes a short exercise which focuses on spreadsheet techniques which you will find useful. How to Access Excel. Students who use the PC’s in Seaver North 113 or those in the computer labs maintained by the computer center will use the Excel program loaded on each PC. Those of you who wish to use your own PC if you have a license for Excel. Please note that portions of this and following exercises will require the Data Analysis add-in which does not come with the standard package. Excel installed on the PC's in the classrooms does contain the extra options. INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTING AND EXCEL PAGE 1 You need to log on to the campus network in order to print and to access your user space. If you are using a computer in Seaver North room 113, click on the Excel icon on the desktop. The following are a few other things to keep in mind when using network applications: 1. Remember to save your work to a floppy disk or preferably to your user space before exiting the program. 2. Remember to log off when you're finished otherwise the next user will have access to your user space. Introduction to Excel. The following example is designed to familiarize you with entering and manipulating data in Excel spreadsheets and will be presented in lab during the Excel demo on the first day of lab. The problem deals with the analysis of a crude sample of sodium carbonate isolated from a dry lake deposit. The sample is dissolved in acid-free water and is titrated with 0.1098 M hydrochloric acid to the equivalence point. Two protons react with each carbonate anion. The following data were found in a notebook. sample # 1 2 3 4 5 6 sample mass (g) 0.1400 0.1511 0.1307 0.1612 0.1488 0.1534 volume of HCl (ml) 20.42 22.13 19.09 23.49 22.12 47.22 1) Start Excel and enter the label “mass(g)” at the top of the first column, i.e. in the A1 cell. Enter the 6 values of the sample mass in the cells A2 through A7. 2) Similarly label the second column “V(ml)” and enter the volumetric data. 3) Label the third cell “n H+” and calculate the moles of protons for the first sample by entering the following in the C2 cell: =0.001*B2*0.1098. The result will appear in the C2 cell. If the attempt to perform the calculation fails to yield a numerical result, the following incantation should exorcise the Excel demons. Clear the offending cell and click on an empty cell in the spreadsheet. If you try again using proper syntax, the procedure should work. 4) Now automatically complete the calculations for the remaining cells (cells C3-C7) by completing these steps: click on the C2 cell, click on the Copy item in the Edit menu, select the cells C3-C7, and click on the Paste item in the Edit menu. 5) Label the fourth cell "n CO3" and calculate the moles of carbonate for the first sample by entering the following in the D2 cell: =C2/2. Complete cells D3 through D7 as you did in step 4. INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTING AND EXCEL PAGE 2 6) Similarly label the fifth column “g CO3(g)” and calculate the mass of sodium carbonate in each sample. The MW of sodium carbonate is 105.99 g/mole. The sequence is calculate in the E2 cell, copy, select, and paste. 7) Finally calculate the wgt-% of sodium carbonate in the sixth column. 8) The volume for the sixth run is clearly incorrect. It turns out to be a typo and the correct value is 22.42 ml. Enter the correct number. Note that the spreadsheet is automatically updated and the corrected results appear in cells C7-F7. 9) Now use the Excel functions to calculate the average, standard deviation, standard deviation of the mean, and 95% confidence interval of the mean. a) Suppose we wish to place the average of the results in the F9 cell. First click on the F8 cell and enter a label, e.g. avg 1-6. b) Next click on the empty F9 cell, designating it to receive the result from the following steps. c) Next click on the following: Tools Data Analysis Descriptive Statistics OK d) A Descriptive Statistics window will open up. Select the following output options: Output Range, Summary Statistics, and Confidence Level for Mean. The default level is 95%. e) Click in the box beside Output Range. Then click in the cell where you wish the report to begin, i.e. its upper left hand corner. f) Click in the box beside the field Input Range. Then using your mouse, select all values of the wgt-% sodium carbonate in the F column of your spreadsheet and finally on OK in the Descriptive Statistics window. A report of the desired statistics will appear in your spreadsheet. The item labeled standard error is the standard deviation of the mean. Note that this utility was written so that you must select a contiguous range of values. g) An alternate approach is required if the data that you wish to select are not contiguous. You may want to do this if you suspect that one datum is flawed. In our example, notice that the result for the fifth run deviates significantly from the average. Perhaps the result is in error. You could copy the data in your INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTING AND EXCEL PAGE 3 worksheet, i,e. duplicate the cells in another section of the worksheet, and then delete the row with the suspected bad datum. h) Alternatively you can take another route which requires a separate pass for each statistic. First click on the cell to hold the result. Click on the following: Insert Function i) An Insert Function box will appear. Select the desired statistic, e.g. AVERAGE, from the list of options and then OK. j) A Function Argument box will now appear. Select the data but not the datum for the fifth run. To choose cells selectively, hold down the Control (Ctrl) key before you click on each cell you wish to include. Click on OK when the data have been selected. k) Similarly calculate the standard deviation and observe that the standard deviation improves significantly with the removal of the suspect datum. l) Finally use spreadsheet techniques to calculate the standard deviation of the mean and the 95% confidence interval of the mean. 10) Save the spreadsheet on your user space or to a diskette by clicking on the Save As item in the File menu. When the Save window appears, select the appropriate drive and provide a unique file name (the extension is .xls) before clicking OK. Get in the habit of saving any work that is important (Save early, Save often!). Do not save your work on the hard drive of lab computers. They are frequently cleaned of extraneous files in order to maintain space for software. 11) Confirm that you have saved something. Close the present spreadsheet by clicking on Close in the File Menu. Then read back in the spreadsheet that you just saved by clicking on Open in the File menu. Select the drive and file name and click OK. 12) Print out your completed spreadsheet. Click on the Print item in the File menu. When the Print window appears, select the printer. 13) Finally exit from Excel by clicking on Exit in the File menu. Exit from Windows and log off of the Novell network. excel.doc, 3 July 1997, WES updated January 2, 2002, JMT; 8 August 2004, WES INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTING AND EXCEL PAGE 4