Homework 3

advertisement

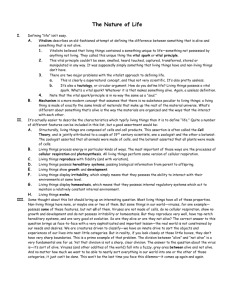

Alex Storer Group: Emma Dannin, Elyse Myers, Genessa Giorgi, Madhu Prabaker, David Morris Section: W 2-3 Cog Sci 101, Assignment 3 When considering the contested concept of life and by extension the contested category living things, we must first analyze its uses in every day language. This discussion should be prefaced, however, by noting that life itself is a very difficult category to discuss. To begin with, a great deal of sentences in American English deal with life in some sort of metaphorical sense. For example, you could tell your friend to “get a life” without implying that they are no longer living. Or you could tell the same friend that “you aren’t really living until you’ve found a purpose worth dying for,” which does not imply that a person is literally dead. My goal is to keep the focus on the most literal meanings of life, and briefly discuss how common phrases reflect the same ideas that support these literal meanings. Additionally, this particular category is difficult because science in general has a fairly rigid definition of what it means for something to be alive. Most of the people with whom I discussed this were familiar with this definition of life, although this almost certainly does not reflect the prevalent viewpoints of speakers of American English. Also allow me to briefly note that all of my quotations come from data linked from the Google search engine (www.google.com), and I will forgo citing them. Searching for the string “it’s not alive, it’s just” yielded several results, most of which suggest some sort of criteria by which one could judge whether or not something is alive. The most common criteria in this small set of data is motion, reflected by “it’s not alive, it’s just muscle spasms”, “it may be moving but it’s not alive”, “it’s not moving, so it’s not alive” and “maybe it’s not alive…but those little white specks do move an awful lot like a living organism”. Each of these is used in a separate context, but all of them reveal a close connection between life and movement. The common phrase “come to life” often reflects literal motion, such as “the statue came to life and farted a message” Another noteworthy phrase is “it’s not really alive, it’s just a clump of cells.” This suggestion that a mere clump of cells does not confer life implies the necessity of some sort of whole entity. For example, “living single-celled creatures can be studied under a microscope” without any doubts of their livelihood, because each one is its own being. This extends very clearly into another important criterion, some sort of biological process which takes place. For example, “of course it's alive. It's a biological mechanism that converts nutrients and oxygen into energy that causes its cells to divide, multiply, and grow.” This definition, in which the speaker has complete faith, elucidates the specific biological mechanism necessary for life in a scientific context. Viruses do not meet this criterion, and are therefore not alive, as many biology textbooks will confidently inform you. This biological imperative also fuels the earlier quote which mentioned “moving along…like an organism”. Another very important criterion for life is growth, which is evidenced in the biological definition given in the above paragraph. Several of my group members specifically mentioned this as an important factor for life, as well, citing that they do not consider a seed to be alive until it has begun to grow. Many consider that a language can be metaphorically alive or dead, and determining this relies heavily on the criterion of growth. “Our language is what they call a ‘living language.’ Which means that it is constantly growing.” Despite the poor grammar, the speaker has explicitly asserted the importance of this particular criterion. Consciousness also plays an important role in evaluating life, which stems from our own human condition and the present scientific understanding that once someone dies he or she is no longer conscious. If you walked into a room and saw a man sprawled out on the floor unconscious, you might consider him dead. The phrase “he’s not dead, he’s just sleeping”, which is very common online, would correct you or anyone else of the overextension of this criterion to the living. Consciousness on its own suggests life, as well, although in the present day it’s very difficult to dissociate consciousness and movement, as conscious beings tend to move around. Consciousness is also bit hairy as there is little in the way of science to explain it, and although treated as a Boolean, may actually have a gradient of some sort. Either way, the speaker in most sentences is going to make an assumption regarding whether or not something is conscious based on what they have observed, and that guides his or her thought process rather than the truth. Now that these criteria are established (motion, wholeness, biology, growth and consciousness), we must ascertain their use and relative importance in determining the presence of life. Clearly, when all are present we meet a very familiar being – a growing, moving, conscious whole biological creature, like a puppy. Also noteworthy is that the puppy can stop growing, stop moving and stop being conscious while still being just as alive as it was previously, as in the case of sleep. If it were killed by destroying it’s nature as a whole being, we would see that, first, dead puppies aren’t much fun, and second, even if its pieces were writhing around and its cells we multiplying, it would not be conscious or whole, and clearly not alive. Science fiction also raises many interesting issues, specifically with respect to the biological component necessary for life in the literal sense. Robots and genetically engineered cyborgs run rampant, and one is often confronted with the question of whether one of these non-biological beings can be alive. If a flower is alive, and it is cut in order to be sold, the question of whether or not it is still alive is an interesting one. Most of the criteria which I have put forth do not apply to plants, as motion and consciousness do not take place to an ascertainable degree. Indeed, the criteria, while the same, are weighted differently for this particular flower than for other forms of life. Now the remaining criteria are growth, wholeness and biology. It still undergoes the biological processes that defined it to be alive earlier, but this alone is not enough to define that flower as living. In this case, the flower is not complete – it lacks its root structure, and may or may not be a real plant because of this. Similarly, because it has lost its roots, it can no longer grow, which I believe to be the primary measurement of life in botanical forms. It is the only perceptible form of change and the most perceptible indication of life. Similarly, my group defined a seed to be alive once it began to sprout, or indicate growth. This further emphasizes the importance of growth, but again, implies the underlying biological process. A flower cannot grow without being biologically feasible, so it is difficult to separate these two. Imitation flowers, for example, which are not alive neither grow nor are biological entities. In terms of determining whether or not something is alive, each example seems to be compared to the prototype to a certain extent. If you identified something as an animal, you would expect it to have share the same criteria which make animals alive, and you would probably rank them in that order. As is determined from the puppy example, the biological mechanisms at work and the wholeness of the being are both crucial, while growing, moving and consciousness are most helpful when the first criteria cannot be determined. A dark, dog-shaped mass lying on the ground in the forest for example, could be watched for a period of time. You might declare it to be dead if you do not see it moving despite the bugs crawling on it, but upon further inspection realize that it is a full and complete tree, very much alive. These considerations must be taken into account when trying to determine whether or not something is alive. Let us now consider the situation with which we are the most familiar, that of human beings. Here arises the central controversy surrounding life, considering questions of abortion. Abortion relies on the PREGNANCY frame, and consists of ending a pregnancy before it has come to term. The debate centers on “when life begins”, or rather, when we can classify a fetus as a living creature. After this point, many believe that abortion is tantamount to murder. This, however, is a different question than whether something is life, as is discussed in many debates on abortion. Pro-life literature tends to focus on the biological processes at work, and the shared properties between unborn children and full fledged human beings. Arguments against this often steer clear of the gritty details, but some focus on what is necessary for a human life, and this is essentially the question at hand. As pregnancies progress, fetuses acquire more and more characteristics of a living human being, including consciousness and motion, and at some point in time become whole entities unto themselves. This is an entirely different question, and the central point of the debate on abortion. Life as a whole, however, is important to determine because being alive confers certain rights and privileges in our society. Knowing the criteria which determine life helps aid in understanding others’ points of view, and the arguments which take place.