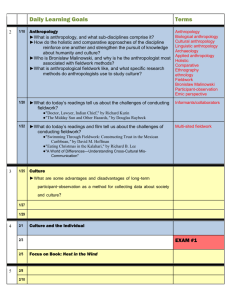

anthropology 2: introduction to cultural anthropology

advertisement

Anthropology 2 – Introduction to Cultural Anthropology Syllabus – Spring Semester 2006 Sections 49926 (MW 9:30-11:10 a.m. Room 834) and 49927 (TTh 11:10 a.m. – 12:40 p.m. Room 5005) The last thing a fish would notice would be the water ~ Ralph Linton Instructor Information Instructor: Chuck Smith. Office: Room 430A. Office Phone: (831) 477-5211 Office Hours: MW: 12:45-1:45 p.m.; TTh 9:30-10:40 a.m.; or by appointment Email: crsmith@cabrillo.edu. I get a lot of junk email – if I don't recognize the sender's name I delete the message without opening it. Therefore, if you send me an email put your name, class name AND section number in the subject box. Course Description Several years ago someone said to me “anthropology is really just the pursuit of the exotic by the eccentric”. In this class we will evaluate just what that means and whether it represents an accurate picture of the anthropological endeavor. For example, are we looking for the “exotic”? Who do we consider exotic and what do we think of as “normal”? What do anthropologists do anyway and how do they think about what they are doing? All of us take for granted certain aspects of everyday life and culture and the point of this class is to explore just what those assumptions might be and what they look like. We want to consider cultural norms that are seemingly different from our own – which can mean, among other things, female husbands, third and fourth genders, witchcraft as a source of infertility and HIV, epilepsy as a result of slammed doors and spirit catchers, the use of fetishes by American baseball players, and so much more. When we learn about these aspects of life elsewhere we begin to understand and reflect on our own assumptions about our everyday lives. We want to be the fish that notice the water! In this course you will be introduced to the basic concepts and findings of cultural anthropology, the systematic and comparative study of human cultural diversity across space and time. Cultural anthropology is the branch of anthropology that primarily deals with living human societies and their culture, as opposed to archaeology, which attempts to reconstruct "extinct" societies, or physical anthropology, which studies the biological side, both past and present, of the human animal. We will touch on these other fields as well, but our main focus in this course will be human cultural systems. We will cover a wide variety of topics in this course that will not only teach us about other peoples and cultures different from our own, but will also help us to improve our understanding of our own society and its customs, values and beliefs; each can shed light upon the other. Topics to be explored include economics and cultural ecology, family and kinship systems, religion and magic, culture change and adaptation, language and communication, and legal and political systems. Contemporary international migrations and communications are bringing us into direct contact with peoples of many regions with different values and ways of life. We are, accordingly, faced with the challenge of tolerating and appreciating other cultural perspectives in order to avoid the dismal alternatives of increased ethnic nationalism, hostility, and violence. Over the next few months, we'll explore the manifold and often highly contrastive ways in which humans in different societies have dealt with, and made sense of, diverse life situations. Along the way, you will learn to understand and (hopefully) appreciate these differences while simultaneously gaining new insights into the patterns and dynamics of your own traditions. Moreover, we will ultimately turn the lens back on ourselves, deconstructing assumptions about 'normalcy' in order to better understand and appreciate cultural differences and human commonalities not only outside but also within our own society. Course Expectations I expect this course will be a fun challenge. It will be a challenge in the sense that it will suggest to you alternative ways of being and knowing. All of which I will stress to you are equally as "valid" (talk to anyone who has taken any class from me before, you will be really tired of hearing me say that...guaranteed). It will offer the opportunity to explore what we and other people think is "normal" and how that is valid, interesting and the means through which we can investigate those ideas. That is, engaging with many of these ideas, the challenges they present at times will be intriguing, unsettling and eye opening. That process should be enjoyable (even though I know it won't always be!) even if what you are learning sounds completely bizarre. I expect you to learn to be critical. That does not mean 1 "critical" in the negative sense, but rather, I expect that by the end of the semester you are able to look for and uncover the assumptions in any argument and can evaluate data from other contexts in culturally relative terms. All knowledge is equally as "truthful" - an often difficult perspective. You can expect that I am personally committed to teaching that philosophy and will provide opportunities, materials and my own theoretical and practical data to that end. Basically, I like to talk about how we tend to naturalize things in the US and how truths really vary worldwide. I welcome your own perspectives in various formats. Other things I expect and you are required to do: You will attend class (I take it as a contractual agreement that you will be here when you signed up for it) You will attend prepared (same deal as above) You will actively participate in class. Participating in and attending class are really important – you cannot participate if you are not there! We will talk more about what "participation" in class actually means (don't worry-I certainly do not expect everyone to speak all the time, there are myriad ways of participating and this includes questions I will ask you to answer on paper, reflections, your own observations outside of class, emails, and the letters I will ask you to write to me), but do realize that it is an important part of the grade and I expect you to be active, engaged members of this class community! I urge you to speak to me if you are concerned about your participation.) You will feel free to come and see me if you are having any difficulties or just want to talk more about the class, anthropology or whatever else you need You will hand in all assignments on time – I will accept a late paper but will penalize it accordingly in order to be fair to others (that means for every day an assignment is due it drops one full grade!) You will feel free to voice your insights and simultaneously respect the freedoms of others to voice theirs (hugely important this one!) 1 urge you to do two things this semester: take advantage of the Writing Center - learning to craft a well written essay and communicate ideas in a persuasive manner are cornerstones of anthropology, your education at Cabrillo College and life itself - they are here to help, use the center. Secondly, make certain that you understand the Academic Integrity Policy here at the University. If you are at all uncertain about what counts as plagiarism please ask - what we learn is grounded in the work of others but learning to interpret and communicate new ideas based upon that knowledge and in our own manner is essential Course Objectives In general, you will be expected to evidence critical, creative, thinking about the course subject matter during class, in assigned writing exercises, and on course exams. Successful engagement with class materials should facilitate your ability to productively participate in cross-cultural dialogue, and thereby more successfully engage with the multicultural world in which we live. In addition, by the end of the semester, you are expected to able to: Demonstrate knowledge and understanding regarding the scope of cultural anthropology. Discuss the concept of culture, the systems nature of culture, and culture’s various manifestations as well as examine cultural phenomena from an anthropological perspective. Understand the concept of ethnocentrism, to develop the skills for recognizing and controlling for ethnocentric biases and for validly understanding other cultural ways. Understand the concept of bio-cultural adaptation. Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the major theories, concepts, ethics, and research methods employed by cultural anthropologists. Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the evolution of sociocultural groups from foraging bands to modern multicultural nation-states. Demonstrate knowledge and understanding regarding the impact of culture and language on human behavior and thought. Provide examples of anthropological insights into many facets of human life, e.g., economic systems, kinship and marriage customs, and global issues. Identify and understand conflicts in multicultural societies. Understand that different groups may have different perspectives on the same historical or contemporary event. Effectively utilize computer resources and the Internet to explore the world of anthropology. Effectively utilize anthropological techniques of research for mini-projects. 2 Engage in critical thinking, analysis, and problem solving about social issues. Effectively participate in group interactions involving members of groups other than their own be it based on ethnicity, nationality, culture, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, class, or physical ability. Appreciate and value diversity and demonstrate sensitivity to cultural differences. Better understand your own society and place within your cultural environment. Recognize your own and others' biases and understand their impact. Please feel free to express yourself in class. Ask questions if you don't understand or need more explanation. Argue intelligently with me – I love it when someone responds with a question or a debate. Human knowledge is not set in concrete – it is changing and evolving all the time. If you have a different view or interpretation of events, speak up! Texts Social And Cultural Anthropology: A Very Short Introduction, by John Monaghan and Peter Just. 2000. (Abbreviated as VSI in the Tentative Class Schedule at the end of the syllabus.) Introducing Cultural Anthropology, by Roberta Lenkeit. 3rd edition. 2007. (Abbreviated as ICA in the Tentative Class Schedule at the end of the syllabus.) In addition to the texts, you will be required to purchase one additional book. I’ll talk more about this in class. You also will be expected to read a number of short articles and/or sections from journals and books. Nearly all of them are available via the world wide web (see the Tentative Class Schedule at the end of the syllabus) or on reserve in the college library. I selected this method of presentation of additional materials as a way to lessen the cost to you of this class. Course Requirements (Readings, Exams, Semester Writing & Research Assignments) As part of this class, you are responsible for active listening, discussion participation, supporting each other in sharing, risk-taking and feedback. This includes keeping up with reading, participating in class discussions, watching videos, and carrying out a small-scale ethnographic study. At the end of this syllabus is a Tentative Class Schedule. Please note that in addition to the required readings from the texts, I have assigned additional materials from various sources (books, magazines, world wide web, TV, etc.). Some of these materials are available only by going to a password protected web site (you will be given the password and web address at the end of the 1st week of class). All weekly reading assignments are to be completed before coming to class. If you cannot get an assignment in on time due to exceptional circumstances, you MUST clear this with me BEFORE the due date. Every late assignment will be docked ONE GRADE PER CLASS MEETING LATE, and I will not accept assigned papers more than two CLASS MEETINGS past their due date. Your competency in this class will be assessed by means of four exams, one map test, and three writing assignments (Letters From the Field, Ethnographic Field Project, and a Book Review). Exams (50 points each = 200 points total) There will be four exams in this course. The exams are scheduled for: Feb. 28 (MW class) Mar. 1 (TTh class) Mar. 28 (MW class) Mar. 29 (TTh class) May 2 (MW class) May 3 (TTh class) June 1 (MW class) May 31 (TTh class) Exam questions are drawn from lectures, videos, readings, exercises and discussions. Each exam contains a variety of testing venues: multiple-choice questions, true-false statements (which require you to say why a statement is false if you believe it to be FALSE), fill-ins, and short essays. The final exam will consist of both objective and subjective questions plus the map test. The exams will be NOT be open book or open note. The map test will require you to locate geographical features and human societies on a small map of the world; it will NOT be open book. 3 Study guides for each exam will be distributed (via the Internet) one week prior to each exam. In general, each exam is based almost entirely on the material contained in the study guide. However, since I'm never sure what we'll be discussing on those days between handing out the study guide and giving the exam, there are bound to be a few questions on each exam that are not on the study guide. Do NOT COME LATE to the exams, or miss an exam. In the case of the former, you will not be allowed to take the exam, and in the case of the latter, I do NOT allow make-ups (EXCEPTION: verifiable medical and/or legal reasons). Map Test (20 points) This is an ONGOING assignment. On the world map that your instructor will distribute at the end of the second class meeting, you are to locate and label Aptos, as well as those regions from where your ancestors came (that is, those ancestors who first came to the Americas). Throughout the semester, as you hear or read about various cultures, locate and label them on your world map. You will use this map as a study aid in preparation for the inclass map test that will be a part of your final exam (you will not be able to use it while taking the test). I will collect your study map May 16 (MW class) and May 17 (TTh) class. After assessing them, they will be returned the following week so they can be used in preparing for the final exam. Letters From The Field (30 points) As part of your participation in this class you are asked to write to me. Every three weeks you will send me a letter (in electronic form) summarizing what you’ve learned since the last letter. These letters must synthesize what you’ve learned from ALL class sources. Do NOT simply recapitulate what you’ve heard, seen, or read. I want your letters to be reflexive. That is, you should spend some time thinking about and writing down your thoughts as they relate to class apart from normative email correspondence. These letters need not be long (as few as 250 words but certainly no more than 500); they can be whatever length you think expresses what you are trying to think about. I am not giving these letters grades per se, but they do count as participation (each letter is worth up to six points). Why, you may ask, are these assigned? Because I think that at times we think and process our thoughts about what we hear or learn or connect throughout the day at different places other than in the classroom. Here is your opportunity to demonstrate your thoughtful, creative, reflective and intellectual ways of synthesizing your anthropological experience at Cabrillo. Letters are due no later than 5 p.m. on the dates given below: 1st letter: Feb. 23rd 2nd letter: Mar. 16th 3rd letter: Apr. 13th 4th letter: May 4th 5th letter: May 25th Ethnographic Field Project (100 Points) Cultural anthropology is rooted in fieldwork, an anthropologist's long-term experience with a specific group of people and their way of life. When and where possible, the anthropologist attempts to live for a least a year or more with the people who way of life is of concern to the anthropologist. The result is fine-grained knowledge of the everyday details of life. Cultural anthropologists get to know people as individuals. They remember the names and faces of people who, over the course of a year or more, have become familiar to them as complex and complicated women, men, and children. They remember the feel of the noonday sun, the sounds of the morning, the smells of food cooking, the pace and rhythm of life. Cultural anthropologists write about what they have learned in documents called monographs. A monograph about a specific way of life, or some aspect of a specific way of life, is called an ethnographic monograph or ethnography. And the people who share information about their way of life with anthropologists are called "consultants" or "respondents" or "teachers" or "friends" or simply as "the people with whom I work." Regardless of the term, fieldworkers gain insight into another way of life by taking part as fully as they can in a group's social activities, as well as by observing those activities as outsiders. This research method, known as participantobservation, is central to cultural anthropology. For your ethnographic research project, I want you to try your hand at fieldwork (participant observation) and then prepare a mini-ethnography about your research and findings. You will spend approximately four hours riding the Santa Cruz Metropolitan Transit buses. I want you to choose two different routes (e.g., the 71 and the 35) and ride each route 5 to 7 times. Each ride must last at least 30 minutes, and preferably 45 to 60 minutes. Try to vary the time(s) and day(s) you ride the same route. During (not after) each of your rides, take detailed notes (either using a 4 tape recorder or standard note paper) on your observations, documenting the setting of your fieldwork, the time of day or night during which you observed and anything that you feel will help paint a picture of your experience. For example, how many people were on the bus? Which route was it? What time? How did the bus smell? What kinds of things did you see while you were riding? What did people do while riding? Where were people going? Did people talk? What did they say? What were people doing? Did anything happen that seemed unusual, ordinary, or interesting to you? Why? What was the weather like? Write down any thoughts, self-reflections, and reactions you had during your hours of fieldwork. At the end of each observation period, type up your fieldnotes, including your personal thoughts (labeling them as such to separate them from your more descriptive notes). Then write a reflective response about your experience (a mini-ethnography) that answers this question: How is riding a bus about more than transportation? You are required to prepare both a rough and final draft of your mini-ethnography. Your rough draft is to be submitted to me at the beginning of class on March 28 (MW class) or March 29 (TTh class) – NO LATE ROUGH DRAFTS WILL BE ACCEPTED. At the end of class I will give your draft to another student for peer editing (you will receive another student’s draft which you will edit). Your rough draft will be returned to you on April 9 (MW class) or April 10 (TTh) class. IF you do NOT submit a rough draft for peer review on the date indicated your final draft can receive a grade of no higher than C. Your finished draft is due in my hands by the beginning of class on May 2 (MW class) and May 3 (TTh class). NO LATE ETHNOGRAPHIES WILL BE ACCEPTED – NO EXCEPTIONS. I have some organizational suggestions for your mini-ethnography. It should be in several parts: Thesis Statement. Every paper has a thesis, that is, a single major point that it is trying to make. Your thesis should be stated clearly in a single sentence in your paper's introduction (usually the first paragraph). Your entire paper should be focused on this thesis, with little deviation. It is essential, then, that the thesis be well stated. A good thesis often suggests a causal relation, for example: "Export agriculture in El Salvador has led to extreme poverty for most peasants." A thesis might also suggest functional or structural relations. For example, “The combination of illness experiences and enrollment in the Treatment Action Campaign and Doctors Without Borders treatment programs has, under certain circumstances, dramatically altered the lives, identities, and futures of people living with HIV/AIDs in South Africa.” In all cases, the thesis provides the analytical focus of the paper. If you have any questions about your thesis, talk it over with me. The very first sentence or two in your ethnography must clearly and concisely say what the ethnography is about. For example, "This paper is an ethnographic description of my participant-observation and analysis of the ______" or "This paper is a life history of a 87 year old woman who immigrated to the U.S. from China in 1939. In addition to "painting a picture" of her life, this ethnography also contains her views on __________." Or, "This paper contains a description of how a custom wooden bookcase is made, beginning with the selection of the proper wood and ending with delivery to the customer. In addition, this paper contains a description of the values and attitudes that are attached to this craft in my consultant's society." OR, "This paper is an ethnographic description of my participant-observation and analysis of the So-and-So congregation of the Such-and-Such religion. This section shouldn't be more than a page in length. Research Methods. Following your Thesis Statement, you should briefly discuss how your carried out your field observations: the setting of your fieldwork, the times of day or night during which you observed, what the weather was like, how many people were on the buses, which routes your rode, what data collection methods did you use (tape recordings, note taking by hand, photos, etc.) This section shouldn't be more than a page in length. Narration. This is where the bulk of your collected data goes. It is NOT to be presented as a laundry or shopping list. Rather, it is to be written in a straight-forward descriptive fashion. Be sure that your details are SPECIFIC AND CLEAR, as if you were describing the customs of a foreign group to an audience that was almost completely unfamiliar with bus riding and riders. You might want to include such information as how the buses smelled, what kinds of things you saw while you were riding, what people did while riding, where people were going, whether or not people talked (and to whom), what they said, and any other thing(s) that happened that seemed unusual, ordinary, or interesting to you. This section’s length is difficult to determine as it depends 5 on how you organize your data and how you tell your readers about the data. However, I do not believe one can do justice to one’s data in less than two pages. In the past some students have chosen to amplify their narration with charts and/or diagrams. Reflexivity. You might organize this section around the discussion of any particular incident(s) that changed the way you understand buses and the people who ride them. Think about your preconceptions and expectations of your subject population, and about why and how such preconceptions have been altered during actual interactions with real people belonging to your subject population. What have you learned -- what do you know now that you didn't know before beginning the assignment? (The mini-ethnographies "Eating Christmas in the Kalahari" and "Shakespeare in the Bush" provide good models of this sort of essay. Both of these are part of your assigned Internet reading.) You might want to include in this section your thoughts on the very process of ethnography itself -- on the benefits and problems of participant observation (or interviewing) as a primary methodology. Be self-reflexive -- how have your own actions (and your social identity) affected the ways in which you viewed buses as forms of transportation and the people who use buses? It's difficult to say how long this section "should" be. Some folks say what needs to be said in one page; others have taken as much as three to four pages. Analysis. So what does it all mean? Of what value is the data you've collected, the things you've learned (or unlearned)? In other words, your mini-ethnography should be a summary of your answers to the basic question posed: How is riding a bus about more than transportation? You may also suggest some hypotheses for further testing that might help explain some of the aspects of your fieldwork and what you have described and which might strike the outsiders as unusual or inexplicable in some way. As with the previous section, it’s difficult to say how long this section "should" be. Some folks say what needs to be said in one to two pages; others have taken as much as three to four pages. Conclusions. While the Narration and Analysis should be objective and focused on what you learned, the conclusions may refer back to the process of data collection and specific thing(s) that you may have learned. This section’s length varies: from one or two paragraphs to two pages. You need to get started on your ethnographies NOW - don't wait until the 4th or 5th week of the semester. Book Review (100 points) From the list of books at the end of this syllabus, select one, read it, and then prepare a review that does several things: (1) describes your understanding of the findings of the anthropologist-writer; (2) explains why you chose this book; and (3) clearly shows in what ways the book is important to you and to the broader audience for which it is intended. You will prepare both a rough and final draft of your book review. The rough draft is due DATE and the final draft is due DATE. Your rough draft is to be submitted to me at the beginning of class on April 16 (MW class) or April 17 (TTh class) – NO LATE ROUGH DRAFTS WILL BE ACCEPTED. At the end of class I will give your draft to another student for peer editing (you will receive another student’s draft which you will edit). Your rough draft will be returned to you on April 23 (MW class) or April 24 (TTh) class. Please note that if you do NOT submit a rough draft for peer review on the date indicated your final draft can receive a grade of no higher than C. Your finished draft is due in my hands by the beginning of class on May 23 (MW class) and May 24 (TTh class). NO LATE FINAL DRAFTS WILL BE ACCEPTED – NO EXCEPTIONS. Although many of us wrote book reports in high school, few of us wrote reviews. Book reports and book reviews are similar. Book reports tend to be a little more descriptive (What is this book about?) and book reviews are usually more persuasive (Why a reader should or shouldn't read this book). Both offer a combination of summary and commentary. They are a way to think more deeply about a book you've read and to demonstrate your understanding. Although a book review, like a book report, spends some time discussing the content of the book, its main purpose is not informational, but analytic and persuasive. The writer, in analyzing the content, format, argument, and context within which the book was written, argues that the book is worth reading or not. 6 Before you write the book review, but after you have read the book, you should make notes on the following areas: The author (Background and qualifications; Writing style; Use of sources - see Bibliography, Table of Charts & Figures; His/her purpose in writing the book) The book’s format (Table of Contents; Section & Chapter Titles; Index; Introduction – which often tells the format, purpose, and intended audience) The content (Introduction/Conclusion; Preface; Chapter summaries; Tables, Graphs, Figures, etc.) How a book review is structured varies from reviewer to reviewer. However, the following general elements of a book review should be helpful: 1. Introduction. Here you want to provide basic information about the book, and a sense of what your report will be about. You should include: A general description of the book: title, author, subject, and format. Here you can include details about who the author is and where he/she stands in this field of inquiry. You can also link the title to the subject to show how the title explains the subject matter. A brief summary of the purpose of the book and its general argument or theme. Include a statement about for whom the book is intended. Your thesis about the book: is it a suitable/appropriate piece of writing about the problem for the audience it has identified? 2. Body. There are two main sections for this part. The first is an explanation of what the book is about. The second is your opinions about the book and how successful it is. Do not spend too much time or paper on this section, as the analysis of content is more important than a simple summary. Simply provide a general overview of the author's topic, main points, and argument. What is the thesis? What are the important conclusions? Don't try to summarize each chapter or every angle. Choose the ones that are most significant and interesting to you. Then you can summarize. 3. Analysis and Evaluation. In this section you analyze or critique the book. You can write about your own opinions; just be sure that you explain and support them with examples. Some questions you might want to consider when analyzing the text are: Did the author achieve his or her purpose? What is the writer’s style: simple/technical; persuasive/logical? Is the writing effective, powerful, difficult, beautiful? How well does the organizational method (comparison/contrast; cause/effect; analogy; persuasion through example) develop the argument or theme of the book? Give examples to support your analysis. What evidence does the book present to support the argument? Give examples: maps, charts, essays by experts, quotations, newspaper clippings. How convincing is this evidence? Select pieces of evidence that are weak, or strong, and explain why they are such. How complete is the argument? Are there facts and evidence that the author has neglected to consider? Here you may use a comparable book on the same topic to illustrate what has been omitted. When writing your evaluation of the text, you should consider the following: Give a brief summary of all the weakness and strengths you have found in the book. Does it do what it set out to do? Evaluate the book’s overall usefulness to the audience it is intended for. What is your overall response to the book? Did you find it interesting, moving, dull? Note why you liked/disliked the book. 7 4. Would you recommend it to others? Why or why not? Conclusion. Briefly conclude by pulling your thoughts together. You may want to say what impression the book left you with, or emphasize what you want your reader to know about it. Writing a good book report requires summarizing a lot of information in a very small space. Follow these steps to make the task easier. STEP 1: Take thorough and careful notes as you read the book. Use Post-It flags to mark pages that contain important passages or quotes. STEP 2: Gather your reading notes and the book and have them by your side as you write your report. STEP 3: Ask yourself, What would I want to know about this book? STEP 4: Look through your notes and decide, based on the length of the book report and your answers to the above question, what is essential to include and what can be excluded. STEP 5: State the main point of the book: Why did the author write the book? Or for fiction, give a brief plot summary. STEP 6: Outline the plot or main ideas in the book. STEP 7: Follow your outline as you write the report, making sure to balance the general and the specific. A good book report will both give an overview of the book's significance and convey enough details to avoid abstraction. STEP 8: Summarize the overall significance of the book: What has this book contributed to the knowledge of the world? For fiction: What does this story tell us about the author's take on life's big questions? And here are some questions to ask yourself BEFORE submitting your review. Does my introduction clearly set out who the author is, what the book is about, and what I think about the value of the book? Have I clearly presented all the facts about the book: title, author, publication details, and content summary? Is my review well organized with an easily identifiable structure? Have I represented the book’s organizational structure and argument fairly and accurately? Have I presented evidence from the book to back up statements I have made about the author, his/her purpose, and the structure, research and argument of the book? Have I presented a balanced argument about the value of the book for its audience? (Harsh judgments are difficult to prove and show academic intolerance.) Tips, Warnings, and Other Admonitions All written assignments are expected to be well conceived, researched, grammatically correct, well written and carefully checked. All papers are expected to be machined printed and have a consistent reference and bibliographic style. If you know or suspect that you are not a good writer, please plan ahead and visit the Writing Center with a draft of the paper before handing it in. The Writing Center is a wonderful resource, and it is a good idea for anyone who is not confident in his or her writing skills to consider a visit. The Cabrillo Writing Center provides individual help to students. The most important step in writing a paper is often thinking it out thoroughly before you begin. Knowing what you'd like to write before you research the topic may seem like a paradox, but it makes a lot of sense – although the paper never turns out as planned anyway. A well-conceived paper comes together easily, and is a joy to write and read. Editing: The Marked-Up Paper No one enjoys getting a paper back that is full of marks. It is often a challenge to our ego to accept that we are not good writers or that our thoughts have not been clearly communicated to our readers. Writing improvement begins with realization. When you get a paper back that has marks on it, do not view these marks as an attack on your character or on your skills as a writer. Rather, think of them as guides to self-realization and writing improvement. Even the greatest writers have said that no author is immune from critiques and suggestions that will improve that author’s written work. 8 Editing is serious and necessary business. Reread the paper before handing it in, and if possible, have a roommate or a friend look it over. Automatic computer spell checking is not enough! The spell checker will not catch correctly spelled words that are used incorrectly: 'two' will pass as 'to' or 'too’ and ‘your’ will pass as ‘you’re’ or ‘yore.’ Such errors are a sign of laziness and sloppy work, and reflect poorly on the student. I want to stress a second option that may help improve your class projects. This is giving your paper to a friend, family member, or acquaintance, perhaps a person in this very class. By having someone else read your paper you again assess potential problems with form and content, but more importantly, your having another person read your work establishes a secondary context of readership. A non-biased reader can often catch mistakes that you have made. As well, social reading is fun! Make sure to proofread carefully ALL written assignments before submitting them to any of your readers. Chucks Fussy Formatting Requirements for All Written Work All papers MUST BE machine-printed. If you do not have access to a typewriter or computer with printer, the Santa Cruz County Public Library System, the Cabrillo Library, and the Cabrillo Student Computer Lab have such machines available for use FREE OF CHARGE. Your cover page should be in the same typeface as the rest of the paper and should include the title, centered on the page, with your name and the course. Be sure to proofread carefully. Points are deducted for typographical errors, bad grammar and misspellings. It is important to present all your written work in a professional style and format in college and in many jobs. Be sure to follow these standards, (or expect the Penalty listed:) 1. Rough And Final Drafts - Your drafts must be machine printed using either 11 or 12 point Times or Times New Roman Fonts. Use standard 8 1/2 by 11 inch white paper of normal 10-20 lb. weight. Write on only one side of the paper. (Penalty 10%+) 2. Double Space - Always double space (except for the title page, quotations over three lines, interviews, charts or lists of data.) (Penalty 10%+) 3. Margins And Pagination - Always leave margins on each page, including the cover and pages of pictures, maps and data. Use 1" margins at top, bottom and both sides. Number all pages at the top or bottom, except the cover and first page. Do NOT justify the right margin. (Penalty 10%+) 4. Title & First Page - On the title page put your own original title in the center of the page and top of the first page. Put your name, date and the class in the lower right corner of the cover. (Penalty 10%+) 5. Organization - Your paper should have a clear beginning, middle and end. A good way to organize your work is to follow an outline like this: a. Introduction b. Topic A c. Topic B d. Conclusion e. References In fact it is helpful to the reader if you put such headings at the beginning of each section! (Penalty 90%+) 6. Formal English - Use college-level English. Unless you are quoting someone directly, do not use slang, pidgin, or conversational forms such as: "don't" for "do not" or "isn't" for "is not" etc. Do not use abbreviations for common words. (Penalty 10%+) 7. Grammar And Spelling - Use good English! Avoid these common errors: (1) Put the apostrophe in possessive words ("...the man's hat.") (2) Keep the tense the same in the report (past, present or future.) (3) Nouns and verbs must agree ("They go..." not "They goes...") (4) Look up the spelling if you are not sure. (Try putting a dot by the word in your dictionary each time, so you will know how many times you looked it up!) (Penalty 20%+) 8. Avoiding Sexist Language - Avoiding sexist language is also extremely important. Statements like "The Religions of Man..." are just not okay. For further reference, and for useful suggestions, check Carolyn 9 Jacobson's excellent guide to gender neutral language (it's available on the Internet at: www.public.iastate.edu/~crlee/student_resources/gender_neutral_language.htm). Or for a longer treatment, try Virginia L. Warren's Guidelines for Non-Sexist Language (also available on the Internet at www.engl.niu.edu/freshman_english/nonsexist.html). (Penalty 20%+) 9. Paragraphs And Sentences - Avoid paragraphs or sentences that are too long or too short. Make it easy for your readers. Paragraphs must have more than one sentence, but should not be a page long. Vary the length, style and complexity of sentences for variety. (Penalty 10%+) 10. Quotations - For short quotes put quote marks before and after the quote - always! For quotes over three lines long, do not use quote marks. Instead indent these lines five spaces on each side from your normal margin and single space these lines. Be sure you put a footnote after each quotation. (Penalty 30%+) 11. Foreign Words – Underline, or put in italics, all non-English words each time you use them, (except for the proper names of people or places.) Also underline or italicize scientific names like: Homo sapiens sapiens (or) Homo sapiens sapiens. (Penalty 10%+) 12. Pictures, Maps, Charts - For each one you use, you must provide a caption or title that explains what it shows. You must also put a footnote just below it, unless it is your own original work, and not a copy, tracing, or rendition of a published picture, map or chart. (Penalty 30%+) 13. Footnoting - Always footnote everything you borrow from another source or person - not just quotations, but also facts, ideas, maps, pictures and data. Use the new style of footnote described on page 2. Put a footnote at the end of each quotation, each picture, and each paragraph containing borrowed ideas or information. Just put the author's last name and the page number of the source. If there is no author, put the first key word of the title. Example: (Ember, p.123) (Penalty 30%+) 14. References - Most papers will require cited sources and all references must be cited. I generally ask that students use the standard Social Science style in referencing cited works within your papers. However, if you are more comfortable with another style (MLA, APA, Chicago), feel free to use it, but please be consistent. A bibliography of cited sources is absolutely required. Please list on the last page all the major books, articles, TV shows, people and places you used for information in your report. (Penalty 30%+) Resources on bibliographic styles include: American Anthopologist Style Guide. (www.aaanet.org/aa/styleguide.htm); The Columbia Guide to Online Style, which includes information on how to reference Internet resources (www.columbia.edu/cu/cup/cgos/idx_basic.html); The Chicago style is explained at www.wisc.edu/writetest/Handbook/DocChicago.html, from the University of Wisconsin at Madison's Writing Center. Also, look at Karla's Guide to Citation Style Guides (bailiwick.lib.uiowa.edu/journalism/cite.html) for extensive links to many citation styles. 15. Plagiarism - Do not steal another person's words or ideas. Use quotation marks around every phrase or sentence you quote and add a footnote. Put a footnote after each picture or paragraph containing a borrowed idea. Do not turn in a paper written by another person. (Penalty 100%+) 16. Proofreading - Have a friend help you proofread your paper carefully BEFORE you hand it in. Correct all errors by crossing them out completely and writing the correction in above them. If you have more than ten corrections on a page, then you must re-write or re-type that page. (Penalty 20%+) 17. Binding - Bind your pages securely with 2-3 staples along the left edge. Do not use paper clips, plastic covers or binders. (Penalty 10%+) The "mini pages" below are a model of what your mini-ethnography and book report should look like. Your Own Title Page # Page # 10 Your Own Title Name Date Class Title Page ___________ _ _ _ _ _ (footnote) _ _ _ (citation) _ _ ____________ __________ _ _ (citation) _ _ _ _ ___________ First Page ____________ _ _ _ _ _ (footnote) _ _ _ _ _ (citation) _ _ ____________ ____________ ____________ ____________ Text Page(s) Conclusion _ _ _ _ _ _ ____________ References: Author etc. Author etc. Author etc. Last Page Grading Criteria In addition to criteria already noted, I grade all written assignments as follows: The assignment is handed in on time: in class and on due date The assignment demonstrates clarity of communication: correct grammar, punctuation, spelling and sentence structure. Assignment has been proofread and corrected for typos, syntax, spelling, etc. The writing is responsive to the assignment: instructions were followed, including format and length. The level of thinking demonstrates: an understanding of course concepts; that facts have been distinguished from opinion; that the concepts are applied creatively or originally. On exams, I evaluate your essay answers as follows: Does the answer have a topic sentence/introductory paragraph? Is the topic sentence/introductory paragraph relevant to the question? Does the answer clearly explain the concept(s) under scrutiny? Does the answer contain an example relevant to the question? On exams, an A answer contains relevant examples from both formal learning materials (lectures, videos, readings, etc.) and one's own experience. A B answer contains a relevant example for either the textbook or personal experience. A C answer is generally correct, showing that the student has an idea of the answer. A D response is barely relevant to the question. An F is irrelevant/unreadable. I’ll distribute a handout during Week 3 that details the exact grading criteria for your various written assignments. Late Work Timeliness of work is a fundamental aspect of the workplace and is equally important in this class. The reason that it is important in class is that knowledge is gained best when you work at it steadily, even when it seems frustrating. Further, knowledge is cumulative, so that understanding what is going on in the 8th week depends upon your understanding of what was discussed in week 3. All assignments are due on the date stated. Any assignments received afterwards will be considered late, and late papers are penalized one full grade per day of lateness, such that an A paper that is one day late will be graded down to an B. Semester Grades Your grade will be calculated by adding up the points on all exams and your semester ethnographic field work / report and then dividing your score by the total possible points (450) to give you your percentage. Grades will be based on the following scale: 450-405 = A; 404-360 points = B; 359-315 points = C; 314-270 = D; less than 270 = F All grades will count – I do not throw away the lowest score or make other exceptions. You will be competing only with yourself in this course, not fighting over a scarce resource (i.e. a limited supply of A's and B's) with other students. It is theoretically possible for every person in the class to earn an A or a B. Please note that the key word here is EARN. Because I expect each of you to do your very best in all assignments, I do not provide any extra credit opportunities in this class. Incompletes It is the responsibility of the student to request, if needed, the assignment of an incomplete grade. I allow incomplete grades only for students who have passed the midterm, have completed their ethnographic research project, who 11 have a legitimate reason for not completing the semester's work and who speak with me two weeks before the final class. My decision to authorize or not authorize an incomplete grade is final. Arrangement for the completion of the course must be made with me prior to the assignment of the "I" grade. This agreement must be written on an Incomplete Course Form. I may allow up to one semester for the student to complete missing requirements. "I" grades not changed by the end of the following semester will automatically become failing grades ("F"). Miscellaneous Comments About This Class Contacting the Instructor: Email is the most reliable way to contact me. If you would like to speak with me in person you should see me during office hours (see above). If you need to talk to me outside office hours call my voice mail (477-5211). Follow the instructions and leave a message with a phone number where I can reach you. I check that voice mail each day Monday through Thursday before 11 a.m. So if you call on Thursday afternoon, Friday, Saturday or Sunday you most likely will get my response on Monday after 11 am. Plan your calls accordingly. I will return your call once. If you are not present or there is no voice mail you will have to call me again. Students with Disabilities: Accommodations for this class are made to comply with the American Disabilities Act. So that appropriate arrangements may be made, I would like to hear from anyone who has a disability, including 'invisible' disabilities such as chronic diseases, learning disorders, and psychological disabilities, which may require some modification of seating, testing, or other class requirements. Please see me during office hours, or after class, or contact me by email and explain your needs and appropriate accommodations. Please bring a verification of your disability from the Disabled Student Services offices and a counselor or specialist's recommendations for accommodating your needs. Attendance: Making this class interesting depends on your constructive participation and respect for one another. This includes arriving on time, not getting ready to go until the class is over, and listening to each other. It means joining into discussions, responding to each other rather than only to me. If you participate thoughtfully everyone can gain from this class. Regular attendance and punctuality are important for both your success and that of the class as a whole. As much of the course material will be presented in lecture, attendance is critical. I take attendance (students are responsible for documenting their presence by signing the attendance sheet) to encourage your exposure to the material available only in class and to encourage your participation and support in class discussions. Whether or not you attend class, you are responsible for material presented in class, what assignments were made, etc., and you will take responsibility for making up missed work. NOTE: I will not reteach class during office hours. You should arrange with someone in the class to share his/her notes with you if you will not be in class. It is not my job to take notes for you. Note: A number of religious holidays (Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, and Muslim) fall during the semester. If it's your customary practice to refrain from any activities, other than those associated with your religious upbringing, on one or more of these days and thus will miss class, please see me for an excused absence and an assignment for the day(s) missed. Videos and Handouts: You will also be responsible for the information contained in the various videotapes and outof-class reading assignments. Many of the videos belong to the instructor or other faculty members, and are NOT available for viewing in the library if you miss them the first time around. I do not loan out ANY videos. The various films and videos included as part of this course are a vital component of the material under study. They are not included as time fillers or for the purpose of entertainment. You are encouraged to take notes during or after each film, and there will be questions about them on the exams. Language Policy: While in the classroom, we will think, discuss and debate as anthropologists. This means that both the instructor and the students will use language that is scholarly and professional, reflecting the fact that we are trying to achieve a greater understanding of the human condition. Learn to express yourself clearly and accurately, and in an intellectual rather than personal fashion. Develop awareness of your own ethnocentrism and make conscious efforts to ameliorate it. Also, be conscious of the language you use to talk about race, ethnicity and gender. For example, no anthropologist publishes articles that refer to "girls" and "guys;" they are "women" and "men." 12 Cell phone / Beeper Policy: Please turn OFF all cell phones, beepers, etc. BEFORE coming into the classroom. If your cell phone or beeper or whatever goes off during class I will make appropriate reductions in your class grade (10% per occurrence). Student Feedback: Feel free to make suggestions or to offer constructive criticisms during the class. I'm always open to possibilities so long as core learning goals are being met. Complaint Procedures: Any student complaints or concerns about this course should first be brought to the attention of the instructor. I will make every effort to resolve the matter to our mutual satisfaction. Should that not happen, the matter may be taken to Nancy Brown, Dean, Human Arts and Social Sciences Division. If you remain in the course after receiving and reviewing this syllabus, I will assume you have read it carefully and understand the mechanics and objectives of the course. It is my hope that this class will be interesting and enjoyable. Your participation in class can greatly enhance this. Welcome to Cultural Anthropology! "...my Aunt Rebeca asks, 'Rutie, pero dime, what is anthropology?' While I hesitate, she confidently exclaims, 'The study of people? And their customs, right?' Right. People and their customs. Exactly. Así de fácil. Can't refute that. Somehow, out of that legacy, born of the European colonial impulse to know others in order to lambast them, better manage them, or exalt them, anthropologists have made a vast intellectual cornucopia. At the anthropological table, to which another leaf is always being added, there is room for studies of Greek death laments, the fate of socialist ideals in Hungary and Nicaragua, Haitian voodoo in Brooklyn, the market for Balinese art, the abortion debate among women in West Fargo, North Dakota, the reading groups of Mayan intellectuals, the proverbs of a Hindi guru, the Bedouin sense of honor, the jokes Native Americans tell about the white man, the plight of Chicana cannery workers, the utopia of Walt Disney, and even, I hope, the story of my family's car accident on the Belt Parkway shortly after our arrival in the United States from Cuba... Anthropology, to give my Aunt Rebeca a grandiose reply, is the most fascinating, bizarre, disturbing, and necessary form of witnessing left to us at the end of the twentieth century..." (Behar 1996: 4-5) Tentative Class Schedule Caveat Lector: The works of humans are imperfect and mutable – changes in this schedule are subject to the instructor's discretion and will be announced in class. If class interest is keen on a particular topic, we will spend more time on it than on others. This is why I label this a Tentative Class Schedule. Frequently I find the class spending more time on some subjects and less time on others. It is, therefore, important for you to come to class regularly in order to stay atop of changes in the schedule. Some of the readings are on reserve in the college library. Others are available as electronic resources through the Cabrillo library’s EBSCoHost program. For the latter do this: 1. Go to the Library’s homepage (libwww.Cabrillo.edu) 2. Click on Fulltext Articles 3. Choose Magazine & Journal Articles (EBSCOhost) 4. Choose EBSCoHost Web which will bring you to the Database: Academic Search Elite page. This is where you begin your search. Week 1 (Feb. 5) – What is Anthropology: the Pursuit of the Exotic by the Eccentric? Readings: VSI pages 1-12; ICA Chapter 1 Eating Christmas in the Kalahari (www.naturalhistorymag.com/master.html?http://www.naturalhistorymag.com/editors_pick/1969_12_pick.h tml) Body Ritual Among the Nacirema (www.msu.edu/~jdowell/miner.html) Videos 13 A Passage to India Week 2 (Feb. 12) – Culture: What A Concept Readings VSI, Ch. 2; ICA Chapter 2 Confessions of a Former Cultural Relativist (http://4sbccfaculty.org/lecture/80s/lectures/Henry_Bagish.html) Unmasking Tradition. EBSCoHost. In the FIND box type in Unmasking Tradition; in the Publication box type in The Sciences; then click on SEARCH. This will bring up a link to a PDF Full Text file for this article. Not a Real Fish. This article exists as a pdf document on the college’s password protected site. Send me an email and I’ll tell you the login and password. Videos Daughter From Da Nang Smoke Signals Week 3 (Feb. 19; the 19th is a Holiday – President’s Day) – Nosey People: Fieldwork As A Way To Learn About Culture Readings VSI, Ch. 1 and 3; ICA Chapter 3 “Getting Below the Surface”, Douglas Raybeck in Naked Anthropologist, and “Some Consequences of a Fieldworker’s Gender for Cross-Cultural Research”, Susan Dwyer-Shick in Naked Anthropologist Not a Real Fish: The Ethnographer as Inside Outsider. On reserve in the college library. Read and bring to class the AAA statement on Ethics: www.aaanet.org/committees/ethics/ethcode.htm Videos Yanomami Rashomon FIRST LETTER DUE by 5 p.m. Mar. Feb. 23rd. Week 4 (Feb. 26.) – Burqas, Rap Songs and Flashing Eyebrows: What are we trying to say? Readings ICA Chapter 4 Shakespeare in the Bush (www.cc.gatech.edu/people/home/idris/Essays/Shakes_in_Bush.htm) Videos American Tongues The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez “The Cultural Translation of Darmok.” Star Trek: The Next Generation, Episode 102. 1991 Stardate 45047.2. 45 minutes. FIRST EXAM: Feb 28 for MW class, Mar. 1 for TTh class Week 5 (Mar. 5) – The Gravy Train: We All Have To Eat Readings ICA Chapter 5 Videos The Baka The Milagro Beanfield War. Week 6 (Mar. 12) – What is all this stuff? Allocating, Converting or Transforming Resources Readings VSI, Ch. 6; ICA Chapter 6 14 “Navigating Nigerian Bureaucracies; or ‘Why Can’t You Beg?’ She Demanded” in The Naked Anthropologist: Tales from Around the World (On reserve in the Cabrillo library). Videos Ongka's Big Moka N!ai: the Story of A !Kung Woman Tampopo Like Water for Chocolate SECOND LETTER DUE by 5 p.m. Mar. 16th. Week 7 (Mar. 19) – Of Love, Lust and Marriage Readings VSI, Ch. 4; ICA Chapter 7 When Brothers Share A Wife (www.case.edu/affil/tibet/booksAndPapers/family.html). This page takes a while to download (about 1 minute) and when you first reach start downloading the pages are all black. Please be patient. Deutsch Section 4:16 and 19 Videos The Wedding Banquet Father of the Bride Moonstruck Week 8 (Mar. 26) – Family Matters, But Who Are These People Anyway: Kinship and Descent Readings ICA Chapter 8 Once Widowed in India, Twice Scorned (www.stpt.usf.edu/~jsokolov/agewid1.htm ) ROUGH DRAFTS OF ETHNOGRAPHIES DUE at the beginning of class on March 28 (MW class) or March 29 (TTh class) SECOND EXAM: Mar. 28 for MW class, Mar. 29 for TTh class WEEK 9 (April 2): Spring Break!!!! Week 10 (April 9) – Too Many Chiefs and Not Enough Indians: The Dimensions of Social Organization Readings VSI, Ch. 5; ICA Chapter 10 Too Many Bananas, Not Enough Pineapples, and No Watermelon at All. On reserve in the college library. Understanding Eskimo Science (www.dushkin.com/olc/genarticle.mhtml?article=13088) THIRD LETTER DUE by 5 p.m. April 13th. Week 11 (April 16) – A Boy Named Sue: Gender and Sexuality Across Cultures Readings ICA Chapter 9 A Woman’s Curse. EBSCoHost. In the FIND box type in A Woman’s Curse; in the Publication box type in The Sciences; then click on SEARCH. This will bring up a link to a PDF Full Text file for this article. What About “Female Genital Mutilation”? And Why Understanding Culture Matters in the First Place. EBSCoHost. In the FIND box type in What About Female Genital Mutilation; in the Publication box type in Daedalus; then click on SEARCH. This will bring up a link to a PDF Full Text file for this article. Videos Guardians of the Flute Tootsie 15 La Cage aux Folles ROUGH DRAFT OF BOOK REVIEW DUE at the beginning of class on April 16 (MW class) or April 17 (TTh class) Week 12 (April 23) – Explaining the Unexplainable: Magic: Science and Religion Readings VSI, Ch. 7; ICA Chapter 11 Why We Want Their Bodies Back. EBSCoHost. In the FIND box type in Why We Want Their Bodies Back; in the Publication box type in Discover; then click on SEARCH. This will bring up a link to a PDF Full Text file for this article. Baseball Magic. (www.sociology101.net/sys-tmpl/baseballmagic/) Videos The Power and the Glory The Holy Ghost People The Crucible Week 13 (April 30) – Doctor, What’s Wrong With My Daughter: Ethnomedicine Readings It Takes A Village Healer. On reserve in the college library. Video A Hmong Shaman in America FOURTH LETTER DUE by 5 p.m. May 4th. THIRD EXAM: May 2 for MW class, May 3 for TTh class FINISHED DRAFTS OF ETHNOGRAPHIES DUE at the beginning of class on MAY 2 (MW class) or May 3 (TTh class). Week 14 (May 7) – Beauty Is In The Eye of the Beholder: Expressive Culture Readings ICA Chapter 12 Video New Orleans’ Black Indians; Bali: Mask of Rangda Week 15 (May 14) – The Sky Is Falling! The Sky Is Falling! How Cultures Change Readings ICA Chapter 13 The Arrow of Disease. EBSCoHost. In the FIND box type in The Arrow of Disease; in the Publication box type in Discover; then click on SEARCH. This will bring up a link to a PDF Full Text file for this article. Steel Axes for Stone-Age Australians (www.cabrillo.edu/~crsmith/steelAxes.pdf) A Plunge Into The Present. (www.ronsuskind.com/newsite/articles/archives/000033.html) Video Cricket in the Trobriands “Who Watches the Watchers?” Star Trek: The Next Generation, Episode 52, 1989, Stardate 43173.5. The Merchants of Cool. (www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/cool/). Watch this, either on your computer or get the DVD at your local rental place. Then write a one page (typed) reflection on how you personally have experienced or witnessed "culture change". Due at the start of the second class meeting this week! (This does not “count” toward your grade points but it is required that you do it!) ETHNOGRAPHIES DUE at the start of the second class meeting this week! – NO LATE PAPERS WILL BE ACCEPTED. 16 Week 16 (May 21) – Welcome to McWorld: Globalization and the Culture of Capitalism Readings: The Price of Progress. On reserve in the college library. Video Behind the Smile; The Journey of Chief Wei Wei STUDY MAPS DUE at the beginning of class on May 23 (MW class) and May 24 (TTh class). FIFTH LETTER DUE by 5 p.m. May 25th. FINAL DRAFT OF BOOK REVIEW DUE at the beginning of class on May 23 (MW class) and May 24 (TTh class). Week 17 (May 28) – May 29th is a HOLIDAY. FINAL EXAM WEEK. Bring a Blue ScanTron to the exam. Section 49926 (MW class): Exam will be given on Friday, June 1, from 7-9:50 a.m. Section 49927 (TTh class): Exam will be given on Thursday, May 31, from 10 a.m. – 12:50 p.m. BOOK LIST Nearly all of these books can be found USED so don’t spend good money on new copies. I’ve seen most of them (at one time or another) at Logos in downtown SCruz. And a few of them are in various local libraries. All of these books have been reviewed (in print, on the web – especially at various “essay” sites) numerous times and I’m familiar with most of the reviews. In fact, nearly all of the “blurbs” below come either from sites advertising these books for sale or from the covers of papers widely available on the web. While I encourage you to look at other reviews AFTER reading the book, when you write your review, please make sure that it is YOUR review. Dancing Skeletons: Life and Death in West Africa by Katherine A. Dettwyler. This personal account by a biocultural anthropologist illuminates important, not-soon-forgotten messages involving the more sobering aspects of conducting fieldwork among malnourished children in West Africa. With nutritional anthropology at its core, Dancing Skeletons presents informal, engaging, and oftentimes dramatic stories from the field that relate the author’s experiences conducting research on infant feeding and health in Mali. Through fascinating vignettes and honest, vivid descriptions, Dettwyler explores such diverse topics as ethnocentrism, culture shock, population control, breastfeeding, child care, the meaning of disability and child death in different cultures, female circumcision, women’s roles in patrilineal societies, the dangers of fieldwork, and the realities involved in researching emotionally draining topics. Readers will alternately laugh and cry as they meet the author’s friends and informants, follow her through a series of encounters with both peri-urban and rural Bambara culture, and struggle with her as she attempts to reconcile her very different roles as objective ethnographer, subjective friend, and mother in the field. First Fieldwork: The Misadventures of an Anthropologist by Barbara Gallatin Anderson. Twelve months in a tiny island village facing the wild North Sea. Anderson takes readers there—to the experience of first fieldwork. Written with wit and insight, fifteen chapters (each exploring a key anthropological concept) chronicle daily life in a Danish maritime community. From the arrival of the Anderson family to their eventful departure, students follow the professional and personal challenges of a culture change study. Forces of urbanization are turning the life (but not the soul) of thatched-roof Taarnby from the sea to the nearby city of Copenhagen. From cooking and culture shock to data gathering and childbirth, First Fieldwork animates the lighter side of fieldwork, its follies and foibles, triumphs and disasters. Anyone who has done fieldwork will identify with the humor and the pathos; anyone planning it will profit from the demystification that Anderson brings to this anthropological rite of passage. It is wonderfully human, thoroughly professional. Guests of the Sheik by Elizabeth Fernea. Elizabeth Warnock Fernea spent the first two years of her marriage in the 1950s living in El Nahra, a small village in Southern Iraq, and her book is a personal narrative about life behind a veil in a community unaccustomed to Western 17 women. She arrived speaking only a few words of Arabic and feeling dubious about her husband's expectation that she adapt completely to the segregated society in order to accommodate his anthropological study. When she left two years later she was an accepted and loved member of the village, inspired for a lifetime of work in Middle Eastern studies. The story of her life among the Iraqis is eye-opening, written with intellectual honesty as well as love and respect for a seemingly impenetrable society. Although the book was originally published in 1965, it surfaced again during the Gulf War in 1991 when many small villages were destroyed in Southern Iraq. This book gives readers a fuller sense of those communities and brings home the cost of war waged against civilians. House of Lim by Margery Wolf. Maps and Dreams: Indians and the British Columbia Frontier by Hugh Brody. The Canadian subarctic is a world of forest, prairie, and muskeg; of rainbow trout, moose, and caribou; of Indian hunters and trappers. It is also a world of boomtowns and bars, oil rigs and seismic soundings; of white energy speculators, ranchers, and sports hunters. Brody came to this dual world with the job of “mapping” the lands of northwest British Columbia as well as the way of life of a small group of Beaver Indians with a viable hunting economy living in the path of a projected oil pipeline. The result is Maps and Dreams, Brody’s account of his extraordinary eighteen-month journey through the world of a people who have no intention of vanishing into the past. In this beautifully written book, readers go on a moose hunt; trap beaver; mourn at a funeral; drink in white bars; visit camps, cabins, and traplines by pickup truck, on horseback, and on foot. Brody’s powerful commentary also retraces the history of the ever-expanding white frontier from the first eighteenth-century explorer to the wildest corporate energy dreams of the present day. In the process, students see how Indian dreams and white dreams, Indians maps and white maps, collide. Men, Women, and Money in Seychelles: Two Views by Marion Benedict. This book, an ethnography of the Seychelles, is presented in two parts: the first by Marion Benedict in the form of a first-person narrative of her experiences with one Seychelloise woman, and the second, a sociological description by Burton Benedict. A man fulfills his obligations to women through gifts of money... In return, women who have much less access to wage employment fulfill their obligations to men who have given money through their sexuality and domestic labour. Nan: The Life of an Irish Travelling Woman by Sharon Gmelch. Nan Donohoe was an Irish Travelling woman, one of Ireland’s indigenous gypsies or “tinkers.” Traditionally, they traveled the countryside making and repairing tinware, sweeping chimneys, selling small household wares, and doing odd-job work. Today, they live on the roadside in trailers and in government-built camps. Told largely in her own voice, Nan’s saga begins in 1919 with her birth in a tent in the Irish Midlands; it follows her life in Ireland and England, in countryside and city slums, through adversity and adventure. Gmelch brings to her task not only the resources of anthropology, but the skill of a sensitive writer and a warmth that allows her to see Nan as a person, not a subject. What emerges is a human story, filled with cruelty and compassion, sorrow and humor, bad luck and good. Nest in the Wind: Adventures in Anthropology on a Tropical Island by Martha C. Ward. During her first visit to the beautiful island of Pohnpei in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, anthropologist Martha Ward discovered people who grew quarter-ton yams in secret and ritually shared a powerful drink called kava. She managed a medical research project, ate dog, became pregnant, and responded to spells placed on her. Thirty years later she returned to Pohnpei to learn what had happened there since her first visit. Were islanders still relaxed and casual about sex? Were they still obsessed with titles and social rank? Was the island still lush and beautiful? Had the inhabitants remained healthy? This second edition of Ward’s best-selling account is a rare, longitudinal study that tracks people, processes, and a place through decades of change. It is also an intimate record of doing fieldwork that immerses readers in the sights, smells, tastes, sounds, and the sensory richness of Pohnpei. Ward addresses the ageless ethnographic questions about family life, politics, religion, traditional medicine, magic, and death together with contemporary concerns about postcolonial survival, the discontinuities of culture, and adaptation to the demands of a global age. Her insightful discoveries illuminate the evolution of a culture possibly distant from yet important to people living in other parts of the world. Never In Anger by Jean Briggs. 18 Anthropologist Jean Briggs spent seventeen months living on a remote Arctic shore as the "adopted daughter" of an Eskimo family. Through vignettes of daily life she unfolds a warm and perceptive tale of the behavioral patterns of the Utku, their way of training children, and their handling of deviations from desired behavior. Nisa: The Life and Words of a !Kung Woman by Marjorie Shostak. The !Kung San (or "Bushmen") are hunter-gatherers who live on the edges of the Kalahari desert. Nisa is the autobiography of a !Kung woman, edited and commented on by Marjorie Shostak. It is divided into chapters dealing with different periods and themes of Nisa's life, beginning with her earliest memories and roughly following the course of her life through to her old age. Each chapter consists of a description by Shostak of the appropriate aspect of !Kung life (drawing on broader anthropological studies) followed by edited (and translated!) extracts from Nisa's own words. The introduction and epilogue set the work in the context of ongoing anthropological study of the !Kung San, and describe the interaction of the latter with the modern world; here Shostak also discusses her own biases and motivations. Return to Laughter by Laura Bohannon (Elenore Smith Bowen). An enjoyable book by an American anthropologist in a small Tiv (Nigerian) village. Honestly portrays life in a foreign culture and successfully probes the relationship between culture, individuality, and community. One memorable part is the recounting of people's reaction to a smallpox ("water") epidemic. Stranger and Friend by Hortense Powdermaker. There are few books which are as informative of what it means to be a field-worker in social science as Hortense Powdermaker's Stranger and Friend. This is just the kind of book needed in anthropology today. It tells objectively, but in warm and human terms, how important research was done. It contributes to methodology and to the history of the science of anthropology. Stranger and Friend is a passionate plea for anthropology as a human discipline as well as a science, as an all-engrossing life experience as well as a profession, and increasingly as a subject in the curriculum of graduate and undergraduate studies. Tell Them Who I Am: The Lives of Homeless Women by Elliot Liebow. Liebow here succeeds in demolishing the anonymity of the homeless. Skillfully blending a social scientist's objectivity with humanitarian concern, he observes women who live in a variety of shelters near Washington, D.C.-how they interact with one another, family and shelter staff; pass their days; and struggle to retain their dignity in the face of rejection by society. Liebow maintains that homelessness is a Catch-22, with few ways out; that homeless women are remarkably supportive of one another; that shelter workers are often dedicated, but also scared and autocratic in spite of their best intentions; that the men in these women's lives seldom offer help; and that homeless mothers are propelled by ties, however flimsy, to their children. Liebow's probing and morally honest report reveals hard truths about the humanity and inhumanity of us all. The Innocent Anthropologist: Notes from a Mud Hut by Nigel Barley. When British anthropologist Nigel Barley set up home among the Dowayo people in northern Cameroon, he knew how fieldwork should be conducted. Unfortunately, nobody had told the Dowayo. His compulsive, witty account of first fieldwork offers a wonderfully inspiring introduction to the real life of a cultural anthropologist doing research in a Third World area. Both touching and hilarious, Barley’s unconventional story—in which he survived boredom, hostility, disaster, and illness—addresses many critical issues in anthropology and in fieldwork. The Parish Behind God's Back: The Changing of Rural Barbados by George and Sharon Gmelch. In the eastern Caribbean the expression "behind God's back" refers to a place that is remote or far away. In this book, the authors look at the changing face of village life in St. Lucy, Barbados' northern and most rural parish. What they find are people whose lives are fully connected to the outside world. One of the first things any visitor to the island notices are youths in baseball caps and T-shirts sporting the names and logos of American teams. Switching on the television, it is easier to find an American sitcom than a Caribbean program. In conversation, it soon becomes apparent that nearly every villager has a relative living overseas and that many have themselves traveled to New York, Toronto, and London. And all Barbadians are aware that the health of their economy depends on decisions made beyond their shores. The Parish Behind God's Back is informed by the authors' research and experiences directing an anthropology field school in Barbados since 1983. The book begins with an introduction to the island and parish, followed by history and macrolevel description of the island economy, before turning to the local scene-- 19 patterns of work, gender relations, lifecycle, community, and religion. The perspective then widens to look at the global forces that most directly affect local people's lives--television, tourism, and travel. An appendix describes how North American college students were changed by living in St. Lucy. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman A compelling anthropological study. The Hmong people in America are mainly refugee families who supported the CIA militaristic efforts in Laos. They are a clannish group with a firmly established culture that combines issues of health care with a deep spirituality that may be deemed primitive by Western standards. In Merced, CA, which has a large Hmong community, Lia Lee was born, the 13th child in a family coping with their plunge into a modern and mechanized way of life. The child suffered an initial seizure at the age of three months. Her family attributed it to the slamming of the front door by an older sister. They felt the fright had caused the baby's soul to flee her body and become lost to a malignant spirit. The report of the family's attempts to cure Lia through shamanistic intervention and the home sacrifices of pigs and chickens is balanced by the intervention of the medical community that insisted upon the removal of the child from deeply loving parents with disastrous results. This compassionate and understanding account fairly represents the positions of all the parties involved. The suspense of the child's precarious health, the understanding characterization of the parents and doctors, and especially the insights into Hmong culture make this a very worthwhile read. Thunder Rides a Black Horse: Mescalero Apaches and the Mythic Present by Claire R. Farrer. The impressive four-day and four-night Mescalero Apache girls’ puberty ceremonial provides the structure for Farrer’s consideration of the ways in which old myths and legends inform contemporary actions and beliefs. Why people behave as they do is as much a focus as is their actual behavior. Through instructions given to Farrer by Bernard Second, her Apache teacher for fourteen years, students gain insight into the importance of narrative, not just in ceremony but especially in everyday living on a contemporary Indian reservation in the American Southwest. Sights and smells are almost palpable as the author provides the best in reflexive ethnography by allowing readers to see her as a person rather than an all-knowing anthropologist. She neither romanticizes nor patronizes the Apachean people, who are presented as people with foibles as well as possessing much worthy of admiration. Women of the Forest by Robert and Yolanda Murphy. When it originally appeared, this groundbreaking ethnography was one of the first works to focus on gender in anthropology. The thirtieth anniversary edition of Women of the Forest reconfirms the book’s importance for contemporary studies on gender and life in the Amazon. The book covers Yolanda and Robert Murphy’s year of fieldwork among the Mundurucú people of Brazil in 1952. The Murphy’s ethnographic analysis takes into account the historical, ecological, and cultural setting of the Mundurucú, including the mythology surrounding women, women’s work and household life, marriage and child rearing, the effects of social change on the female role, sexual antagonism, and the means by which women compensate for their low social position. WHAT IS CULTURE? Culture is INTEGRATED One of the central characteristics of culture is that it is integrated. In The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, the 20 author Anne Fadiman (Aptos Library Reserve: RA418.5.T73 F33 1997) recounts the story of a young Hmong college student who was asked to briefly describe to his French class how to make la soupe de poisson or fish soup. The story illustrates the Hmong philosophy of interrelatedness. The student explained that to make fish soup you must first have a fish, to have a fish you must first go fishing, to go fishing you need a hook, to select the right hook you must know the type of fish, how big its mouth is, the terrain, the environmental conditions, the streams where fish reside, and their habits and movement patterns. Once the fish is caught, you must know how to clean and prepare it, you must select the right seasonings and broth, you must know the eating preferences of those who will eat the fish, and, finally, the fish soup should be served in a pleasing fashion and at the right temperature and time. Culture is LEARNED Culture is ADAPTIVE Culture is BASED ON SYMBOLS Culture is SHARED – but PARTICIPATED IN DIFFERENTIALLY Culture ORGANIZES THE WAY PEOPLE THINK ABOUT THEIR WORLD 21