proposal for tim PhD (1)

advertisement

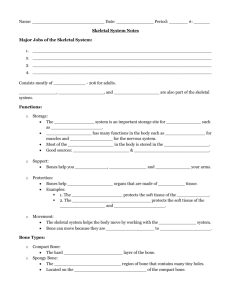

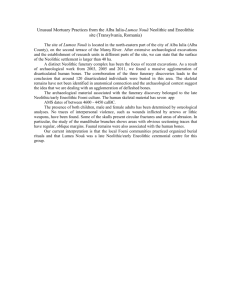

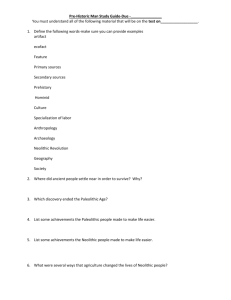

1 Early medical practice in the Neolithic period (2000-4000 BC) Sex, Drugs, Rot and Roll: An investigation into Neolithic Doctoring practices via visual and chemical analysis. By Ellen-Jayne Bryant PhD Proposal 2 Abstract This study will use a selection of injured and diseased skeletons from the Neolithic period (4000-2000BC) to ascertain signs of medical intervention and assistance, the results will support the theory that this period in time represents the first type of “care in the community”, in which basic human anatomical structure and knowledge of medicinal plants would have been essential. This study will use a combination of two methods, the visual anthropological assessment of the bone (to indicate the injuries/disease) which will be used in conjunction with samples of the bone taken to analyse using direct Gas Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), for trace elements of simple chemical compounds, namely narcotics that could have been administered and ingested at the time of death. Skeletal material from the Neolithic period would be sought from, The Museum of London, Salisbury Museum, and The Museum of Devises. Anthropological analysis via a visual method can be challenging, although broken bones can be apparent, the interpretation of whether these bones have been “set” in accordance with our current medical practices awaits to be seen, the skeletal remains will also be assessed for other injuries and infections which could have been treated with medicinal narcotics, specifically those that could be tested using the GC-MS technique. This study will focus on testing the inner sections of the spongy bone material in the long bones; this section has the highest blood supply and offers the best source for identification of simple chemical compounds that are associated with medicinal and poisonous plants that would have been widely available during the time period. Overview of the general area and discipline Ortner (2011) concludes that proposed research which incorporates linked scholarly/scientific disciplines offers “added value and frequently provocative, exciting new knowledge” . The proposal here links the scientific disciplines of Archaeology, Anthropology and Chemistry, with a view to offer insight into early medical practices. In Archaeology the Neolithic period (4000 - 2000 BC) is widely recognised as being pivotal in human history because it marks the time when large populations of people shifted from a nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a more settled existence dependent on agriculture as a major food source. As communities came together 3 evidence has suggested that these events would sometimes be problematic with fighting and even possible warfare (Jordana et al 2009). Evidence for this has been gathered from archaeological excavations from around the world during the last century often, however, the human remains and artefacts do not provide complete answers to exploratory research questions, and so holistic techniques from the field of anthropology can be used to make sense of supplement sparse findings (Gravlee 2011). Archaeologists and anthropologists use both empirical data from the field, in the form of bones and monuments to make basic descriptions and classifications, to try and piece together what kind of medical behaviours and practices were common in this period. This has given rise to the discipline of paleomedicine/paleopathology, however it is worth noting that much of the current research demonstrates an understanding of inter-social upheaval concentrating on the specific causes of the injuries themselves and how they could have been inflicted, which gives rise to the popular belief of a rather turbulent time in prehistory, often avoiding the more caring side a larger community settlement could offer. This research does not seek to counter this argument but to provide insight into the other side of human nature, which demonstrates empathy and the willingness to help those in need, which fundamentally separates humans from most animals. It is important to the present and future of paleopathology (archaeological skeletal remains which link interactions of pathology from the past to the present and vice versa) to move beyond the boundaries of basic descriptions and general classification into more engaging and integrating themes using broader interdisciplinary approaches (Ortner 2011) Aim The aim of the study is to explore the evidence that is present in Neolithic skeletal remains, both visually and chemically, in order to illuminate medical practices of the Neolithic period in particular. Objectives The objectives are to conduct a visual survey and then a targeted analysis using GC-MS, looking for narcotic or other chemical traces, and to interpret the remains holistically including any new evidence found. 4 Literature review The Neolithic period (4000 – 2000 BC) has been a major topic for discussion in academic papers for many years. As the period has no written records interpretation of lifestyle and health often comes from archaeological and anthropological assessments, triggering academic minds to offer their version of events that occurred so long ago. The literature available offers a vast and extensive library dominated somewhat by the concentration on burial practices of the time (Thomas 1999), indeed excavations of burial sites, especially in Egypt but also across Europe and in the Americas provide the largest sources of human bone material for analysis (Lubell et al 1994). Funerary rights and the deposition of human remains is, however, not without its problems, like access to ancient burial grounds, such as those in the Valley of the Kings, in Egypt to the more common problems that face most archaeologists and anthropologists during excavations, in that the bones are subjected to various processes ranging from burning, poor preservation, selected preservation of specific body parts, and differential mortuary treatments. All of which have a significant impact on the bone material available (Murphy and Gaither 2011). Various kinds of positioning in different types of ground leave traces on the bones which add layers of complication to scientific analysis, which is particularly evident in the excavation of graves across a cemetery (Pers. com Betlovaic 2010). In some cases incomplete samples survive, with uneven distribution due to geological rather than historical variation, which makes it difficult to form a complete picture. Human bones are very strong with fracture and healing rates being a topic of extensive research over the past 50 years. Skeletal fractures happen when bone absorbs sufficient energy under mechanical loading to fail resulting in cortical discontinuity (fractures) (Harwood et al 2010). Traumatized bone has a specific sequence of healing events through haemostasis, inflammation, clearance and repair, regeneration and finally resulting in remodelling (Winet 1996) after remodelling has occurred the scarring cannot be seen microscopically or macroscopically, which eventually leads to no evidence that the injury existed in the first place (Harwood et al 2010), it is also worth noting that the rate of healing decreases with age (Mayer et al 2001). Bone has a high blood supply and simple fractures are healed enough to function at around 6 weeks, although the health and age of the individual will have an extensive 5 impact on this rate (Skak and Jenson 1988) the high blood supply differs between cortical and trabecular bone according to Oflaherty (1991) blood flow differs to the two types of bone with estimates of 0.090 ml/min/g to trabecular bone and 0.013 ml/min/g to cortical bone, therefore the trabecular bone would offer a better chance of finding trace chemical compounds absorbed and deposited at the time of the individuals death (Baselt et al 1975). Chemical compounds from narcotics found in blood have been a focus of medical research for some time; (Foerster et al 1978, Christians et al 2000, Baselt et al 1975, Gergov and Vuori 2003), however the chemical compounds found in bone are more limited and tend to focus on heavy metal poisons. One study looked at the aluminum absorption and retention in the brain and bone of rats the results showed the a significant uptake of aluminum, the samples of bone were tested using graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy (Slanina et al 2009) with similar studies completed on lead and other heavy metals (Freeman 1996). to date there has been no attempt to identify anesthetics and analgesics in human bone, either in a modern sample or an archaeological sample, it must be assumed that concentrations of simple chemical compounds (simple because more complex compounds are likely broken down by the surrounding soil components) that are found in medicinal plants that would have been used in the Neolithic could be indentified in bone samples of the same period. Lessa and Guidon (2002) asked whether there is evidence of prehistoric pathology which would have needed treatment; in conclusion they identified a wide range of ailments including dental abscesses, osteoarthritis, and fractures, and some work has been done on dental evidence and diet (Lubell et al., 1994) Paleopharmacology is the study of medicinal remains from archaeological sites (Reinhard et al 1991). Evidence has suggested that knowledge of medicinal plants extends far beyond the ancient Egyptians (Nunn 1996, Merlin 2003). The development of such knowledge could have been trial and error, but some plants offer key insights into their healing abilities, known as the doctrine of signatures for example yellow plants like dandelions (Taraxacum Officinale) have properties that aid in Jaundice and urinary infections, the heart shaped leaves and red flowers of the Hearts Ease (Viola Tricolour) have medicinal properties that aid cardiac problems 6 and blood disorders, both of these plants and more have been used by the ancient Mayan, Chinese, Inca and Indian tribes for thousands of years (reference……). Merlin (2003) looked at the Eastern Hemisphere for use of psychoactive plant usage in pre-historic cultures and indicates that pottery depicting particular medicinal plants is evidence of this, while Shafik and Elseesy (2003) accredited the Ancient Egyptians with the use of caster oil, Marijuana, opium, and beer all of which have medicinal uses. It has been known for some time that primates use medicinal plants with Monkeys and Apes using plants that act as analgesics, anti-microbials, antiinflammatorys, and fertility regulators (Chaves and Reinhard 2005). Further research in Brazil looked at skeletons and hair samples which provided evidence of pathology that would have needed knowledge of traditional medicines (Chaves and Reinard 2005), however the ancient Egyptians developed the earliest known recorded systems which details medical treatments, with scholars having various interpretations from the hieroglyphs dating around 1820 BC, from which 2000 remedies from preparation to dosage have been deciphered, covering a wide range of ailments (Rosalie 2008). Some Neolithic bone samples excavated show evidence of healing, but it is not certain that this is a result of medical intervention. The large number of trephined skulls found in Europe in Neolithic deposits, and somewhat later also in Peru, is however, incontrovertible evidence of medical activity (Ackerknecht 1968). McKenzie (1936) theorizes that the purpose of scraping a hole in the skull was to cure giddiness or epilepsy but it is unclear what evidence can be drawn to point to this conclusion, other than that no trauma is evident in the bones, which could otherwise explain the hole. The Peruvian examples do show evidence of bone trauma. The differences in these two methods can be seen in the shape of the hole, which is shallow and pond-shaped when scraped, and jagged in later techniques. There is some evidence of medical and surgical practices in cave painting, such as finger amputations, but it is presumed that these are motivated by religious meanings rather than any pathology (Ackerknecht 1968). It has been noted that various protocols exist for reporting palaeo-trauma but the majority of investigators modify these methods to suit their own needs and research problems, thus creating incomparable primary data (Judd 2002), however specific studies range from bone loss to fracture patterns and healing rates, Agarwal et al 7 (2010) looked at Neolithic bone samples to ascertain whether cortical bone loss (associated with old age) from the Catalhoyuk community in Turkey led to observable fractures in the bones, the results were interesting with the eldest females showing signs of bone loss but there were no evident fractures. further studies have compiled extensive evidence of warfare and violence, via interpretation of skeletal injuries and fractures, with some notably recognising healing patterns in various fractured bones, but failing to state or investigate any possible intervention from a medical stance, for example Jordana et al (2009) studied Iron age nomadic tribes and interpreted long bone trauma on 10 individuals from Pazyryk tumuli in the Mongolian Alti, they note peri-mortem trauma with 43% of the sample showing evidence of fractures with evidence of healing but there is no suggestion of medical intervention, yet they acknowledge this is a high percentage to have healing injuries, Judd (2011) also observed healed/healing injuries on a skeletal collection dated from the Kerma period 2500- 1750 BC, noting the stages of healing but again no explanation as to whether medical intervention had occurred. One particular discovery in 1991 of a mummified Neolithic body in the Tyrolean Alps, named “Ötzi” is a very valuable source of information on Neolithic medicine, not least because it preserves a man in the middle of his life extremely well along with his clothing, tools and possessions, but the body was found with a pouch containing fungus samples (Whittle 1996). The mushrooms were not of the hallucinogenic type but were known to have antibiotic properties (Fowler 2000). A recent article in the lancet highlights the fact that the iceman’s woody bracket fungus Piptoporus betulinus contains an active compound, agaric acid, which has laxative effects and may have been a deliberately administered medicine against intestinal parasites, the eggs of which were found in the Ice Man’s rectum (Capasso 1998). Another feature of this specimen is that it shows intriguing evidence of tattoos. Some of the tattoos may have been purely decorative, but some of them seem to be suitable as location points for a procedure akin to acupuncture because they consist of simple geometric shapes arranged in linear formation on the back and legs, in a manner strikingly close to modern acupuncture charts (Dorfer et al 1999). Further tattooed specimens have been found in Siberia (Rudenko 1970). 8 This proposal aims to investigate the Neolithic period in relation to discovering the earliest medical society, as there are no written records the assessment will use a combination of thorough visual examination and modern GC-MS testing. The skeletal remains would have to have evidence of trauma that would have needed medical assistance, however the individual would have died as a direct result of the injuries (within a defined timescale of no more than 2 months) the injuries would have to be evident to support the possibility of ingestion of narcotic material for the relief and recovery of the individual. GC-MS testing techniques have been used on organic residues of 958 British prehistoric pots to trace dairy material (Copley et al., 2002) and a similar method applied to Neolithic bone may bring to light significant information on medical practices of that time. Statement of methodology Timescale 3 Years 9 References Ackerknecht, E.H. 1968. A Short History of Medicine. Revised edition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Baker, P. and Carr, G. (Eds.) 2002. Practitioners, Practices and Patients: New Approaches to Medical Archaeology and Anthropology. Oxford: Oxbow. Capasso, L. 1998. 5300 years ago, the Ice Man used natural laxatives and antibiotics. The Lancet 352, Issue 9143, p. 1864. Clark, R.P. 2000. Global Life Systems: Population, Food, and Disease in the Process of Globalization. Oxford: Rowan and Littlefield. Copley, M.S., Berstan, R., Dudd, S.N., Docherty, G., Mukherjee, A.J., Straker, V., Payne, S. and Evershed, R.P. 2002. Direct chemical evidence for widespread dairying in prehistoric Britain. PNAS 109 (8). Available online at: http://www.pnas.org [Accessed on 14th Feb 2012]. Dorfer, L., Moser, M., Bahr, F., Spindler, K., Egarter-Vigl, E., Guillen, S., Dohr, G. and Kenner, T. 1999. A medical report from the stone age? The Lancet 354, pp. 1023-1025. Available online at: http://www.utexas.edu [Accessed on 11th Feb 2012]. Fowler, B. 2000. Iceman: Uncovering the Life and Times of a prehistoric man found in an Alpine glacier. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Gravlee, C. 2011. Research Design and methods in Medical Anthropology. In M. Singer, and P. Erickson, (Eds.). A Companion to Medical Anthropology. Oxford: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 69-92 Lewis-Williams, D. 2005. Inside the Neolithic mind: Consciousness, cosmos and the realm of the gods. London: Thames and Hudson. Lubell, D., Jackes, M., Schwarcz, H., Knyf, M. and Meiklejohn, C. 1994. The Mesolithic-Neolithic transition in Portugal: isotopic and dental evidence of diet. Journal of Archaeological Science 21, pp. 201-206. McKenzie, D. 1936. Surgical Perforation in a Mediaeval Skull with Reference to Neolithic Holing. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 29, pages 895898. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [Accessed on 3rd Feb 2012] Rudenko, S.I. 1970. Frozen tombs of Siberia. London: J.M. Dent and Sons. Sigerist, H.E. 1987. History of Medicine. Second edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10 Singer, M. and Erickson, P. (Eds.). 2011. A Companion to Medical Anthropology. Oxford: John Wiley and Sons. Thomas, J. 1999. Understanding the Neolithic. Second Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Whittle, A.W.R. 1996. Europe in the Neolithic: The creation of new worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.