Richard D - University of Kent

advertisement

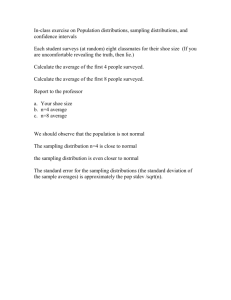

Richard D. Harrison March 2005 ‘Copyright Laws are Too Harsh for Musicians Who Sample’ Intellectual Property Law: LW556 Supervisor: Alan Story Word Count: 5227 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Glossary 1 Sample 1. Ascertain the momentary value of (an analogue signal) many times a second so as to convert the signal to digital form 2. A small part of a song which has been recorded and used to make a new piece of music Sampler 1. An electronic device used to copy and digitally manipulate a segment from an audio recording for use in a new recording 2. A person that takes samples Sampling The technique of digitally encoding music or sound and reusing it as part of a composition or recording. Judy Pearsall (ed), Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 10th edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2002) 1 2 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Abstract The emergence and advance of digitisation enabled new ways of manipulating music and saw the birth of new genres. Sampling can been seen to be at the forefront of this but is a copyright minefield due to the concepts of ownership and unauthorised derivative works. The strict judicial interpretation of what constitutes an unauthorised sample significantly stifles the creativity of musicians who rely on the use and manipulation of samples to create ‘new’ music. Laws dictate that this music is not really ‘new’ at all. Musicians should be able to protect their work and heavy unauthorised use of a single sample should be restricted though this dissertation argues that the combination, disguise and reworking of sampled ‘snippets’ should be free of the stranglehold of copyright and not susceptible to infringement action. I argue that the ‘solution’ of sample clearance is an unaffordable reality for aspiring musicians and though Creative Commons is an attractive prospect its aspirations will also go unfulfilled. Copyright laws are exploited by the dominant forces in the music industry and can be seen to have had a direct effect on the ‘sound’ of the genres who rely on them thus changing their essence altogether. 3 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story And I’ll be damned if I hear another person say That isn’t music because they’re not real instruments you play Narrow minds will say this But how many people can use a computer and play this Call me a rapist But we take you to levels (you never even knew) JamesNow some young people know you’re name Bring fame to the dead and make Curtis sound hard-core Now who could ask for more? You want to change the law And I deplore what you said about the way we made this Sampled the drums but it don’t sound like how he played it Music always stems from other people Listen to the radio The same melodies played time and time you know Rave comes from electro Electro comes from disco You can put it all in the same mix Thrash beats metal guitar from Jimi Hendrix and punk Hip Hop from the funk And some call it junk You want to stop the chain of music, you’ll f*** up the whole system And every single musician will be a victim . --Braintax 2 2 Braintax, Chips on My Shoulder, on Fat Head EP (Low-life Records 1992) 4 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Introduction As opening quotations go, this must seem spectacularly crass and severely lacking in academic propriety. But context is all. Joseph Christie AKA the ‘underground’ UK hip-hip pioneer and producer Braintax, expresses his disdain for the prejudicial views of the conservative world against musicians who use the digital sampler as their exclusive tool of musical expression. The capitalist construct of the ‘underground’ in the music industry is a term synonymous with notions of impropriety and illegality. I use this lyric as an ironic gesture of support to the sonic ‘outlaws’ of the underground, the digital samplers who search for music of a bygone era, resurrect and recontextualise it, thus giving it a new lease of life as part of a new contemporary musical work. If an artist is not established and signed to one of the labels at the head of the music industry who can afford to pay for sample clearance, current copyright laws will often serve to deny any large scale commercial release of an independent sampler’s music. The aspiring electronic musician’s economic incentive to create is being diminished by the stranglehold of the industry’s dominant record labels who exploit the statutory provisions in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 as a tool of oppression. The sample clearance system as it stands has the force of the law behind it and either or both need to change to ensure creativity and the production of new original sample based music. The law at present does not function to cater for the 5 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story shift that has occurred in popular culture and the advancement in music technology, it stifles creativity and acts as a barrier to new aspiring producers. Sampling: Lazy Composition or Creative Transformation? There are possibly two contrasting schools of thought on digital sampling: 1) The ‘Copy Right’ maintain sampling is a lazy technique of music production as it extinguishes the function of the musician, a producer can obtain what he needs from a single recording so a musician is no longer needed. However, I argue that although this may be true to some extent, the requirements of a producer may not make this financially viable. If a producer wishes to sample an orchestral track, then the cost, time and logistics of hiring an orchestra to fulfil his needs for possibly a five second ‘sample’ that he will loop, makes this simply impossible. However, it can be argued that if the record companies get involved when a producer must clear his sample, then the cost of clearing it would be higher than hiring musicians to fulfil his needs.3 This view of digital sampling favours a strict notion of the ownership of intellectual property therefore sampling is essentially theft of a past-musician’s work if permission is not cleared. This Chris Castle: Senior Counsel, Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP at CD Baby Independent Music: Future of Music Coalition - Future of Music Summit May 3rd 2004 http://www.cdbaby.net/fom/000013.html (Acessed 18 February 2005) 3 6 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story view maintains that all sampling is lazy regardless and intellectual property laws exist to protect past creators. 2) The contrasting idea held by people who could be termed the ‘Copy Left’ favours the idea that intellectual property laws should also promote creativity. Digital sampling is a thoroughly creative process and although using previous copyrighted recordings in its creation, a unique sound collage is created by a sampler combining this arrangement of sampled snippets. Samplers should not be strangled by restrictive copyright laws as the sample of the recording is quantitatively insubstantial. I maintain a more liberal standpoint which does lean towards the Copy Left but with qualification. I argue ‘good’ sampling and production should be exempt from current copyright laws however ‘lazy’ sampling should still be subject to royalty fees. However, this is presents a thorny legal issue as what constitutes ‘good’ or ‘lazy’ sampling. The law purports to be neutral to aesthetics as it will happily grant copyright in a good or bad book, an uninteresting or superlatively beautiful song. The conflict between sampling and copyright law simply brings this argument into full focus. 4 It is difficult to define what ‘good’ production using sampling is on paper. Samplers often only use a few notes from a pre-recorded musical work and Duke University School of Law: Music and Theft: Technology, Sampling and The Law. Video presentation, Panellist 1 of panel 1: Anthony Kelley at: 00:05:39 http://realserver.law.duke.edu/ramgen/musicandtheft2002/musicpanel1.rm 4 7 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story combine it into an entirely new multi-layered new musical work wherein the sample is still perhaps slightly recognisable but it is only minimal. In my opinion, by doing so, they have not used a substantial part of a previous recording in its quantitative definition. However, they may have used the most readily identifiable small segment of the track so qualitatively this amounts to a substantial part. If the sample is small, it should be free of illegality as the original performer’s or composer’s effort into producing or playing that single note or phrase is minimal however an entire rhythm is different and original owners of copyrights should be protected.5 This area of the law is a particularly grey area. Producers want guidance; black and white rules and principles of how they can conduct creative legal sampling of pre-recorded music. Producers want a quantitative decision which would permit minimal use without sample clearance being needed, a rule that permits samples of under 3 seconds for example. Anything more than this would be subject to royalty fees on a sliding scale as to the extent of the sample. A ruling such as this could, if obeyed enable many new artists to emerge from this great incentive to create and achieve copyright protection in their own right. This is why Vanilla Ice had to settle out of Court with David Bowie and Queen for his hit’ Ice Ice Baby’ which heavily sampled the rhythmical section of the Queen/David Bowie hit ‘Under Pressure.’ Royalties were held at 50%. Puff Daddy for his hit “I’ll Be Missing You” heavily sampled the Sting and Police hit ‘Every Breath You Take’, royalties in this out of court case were 100%.: Vanilla Ice, Ice Ice Baby on To The Extreme (SBK Records 1991); Queen, Under Pressure on Hot Space (EMI: 1982); Puff Daddy, I’ll Be Missing You on No Way Out (Bad Boy Entertainment: 1997); The Police, Every Breath You Take on Synchronicity (A&M 1983) 5 8 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Digitisation and the technology behind sampling 6 Before the emergence of digital audio and the endless opportunities it offered, the hip hop DJs of late 1970s black urban America were the first pioneers of live ‘sampling.’ 7 It is important to understand the emergence of a genre which discarded all previous musical conventions, rules or ethics, in understanding why it clashed with copyright to the extent that it did. The hip hop DJ would use two turntables to confront their mainly African-American audience with environment additional around them. acoustic Snippets effects taken from from television the jingles, media political speeches, movie soundtracks and video games were commonly inserted into these live-mixes to create a collage of sound. 8 By doing so, the DJ’s would thus use the turntable as an instrument of its own. However, as DJing was a manual technology, its range of effects was as limited as the manual dexterity of a lone individual. 9 The invention of the digital sampler in the late 1970s was only enabled with the introduction of digital audio. Digital audio enabled recorded sound to be represented in binary code, hence computers could be involved in The concept of sampling is highly technical in nature and thus texts are peppered with unfamiliar terminology or jargon. A Sample is different from to sample and a sampler has dual meanings therefore please refer to the glossary above for further guidance and an explanation of the terminology I am using (See glossary above) . 7 Disc Jockeys. Kool Herc, Africa Bambaataa, Grand Wizard Theodore and Grandmaster Flash were the main pioneers in this era. 8 J.J.Beadle, Will Pop Eat Itself? Pop Music in the Soundbite Era(London: Faber and Faber Ltd. 1993) 79 9 D. Sanjek, ‘”Don’t Have To DJ No More”: Sampling and the “Autonomous” Creator, (1992) 10(2) Cardozo Arts and Entertainment Law Journal 607, 612. 6 9 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story sound reproduction for the first time. Opportunities to distort music in the analogue format were limited though this new technology enabled this with ease. Although the first samplers had a limited capabilities, modern samplers are able to distort, speed up or slow down the sample, play it backwards, filter and isolate individual components, loop them, rearrange them, an almost endless number of possibilities to re edit the sample. The samples taken from different records are then layered in a compositional arrangement. An entire drum set can be pieced together from single strokes from many different records. 10 Initially samplers were very costly but economies of scale soon enabled the price of the sampler to tumble and thus the technology was soon within reach of the consumer to exploit its capabilities.11 The sampler was and is a very democratic tool which allows even those with little or no formal training to create their own music. David Sanjek recognizes: ,“It is a longstanding practice for consumers to customize their commodities, command their use and meaning before they are commanded by them.”12 Consequently, hip hop DJ’s gleefully embraced the digital sampler as it provided the necessary stepping stone to record and digitally manipulate Alan Light (ed), The Vibe History of Hip Hop (New York: Three Rivers Press 1999), 170 “The first digital sampler appeared - the Fairlight CMI (Computer Musical Instrument).initially cost £20,000 and, ironically, the manufacturers added the sampling hardware at the last minute because they didn't see a use for it at the time. “ – Zero G Digital Audio: About Copyright and Sample CDs http://www.zerog.co.uk/index.cfm?articleid=39 (Accessed 14 December 2004) 12 Ibid 607. 10 11 10 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story the live collage of sound they created. However, the disregard of musical convention, rules and any type of formalities in their art form was instrumental in bringing a clash with copyright law and the owners of the samples they used. The introduction of the sampler engendered a genuine revolution in the way hip hop was made. With the sampler, hip hop groups were able to make modern music out of classical sounds to capture the quintessential funk and maintain the gritty authenticity of old tracks re-recorded on state of the art equipment. The introduction of the sampler raised great controversy, raising the question of whether this practice was art or thievery. Certainly it was an homage to resurrect the hits of the past and transform elements of them or combine many hits to make a new contemporary work, however the record labels did not see it this way. Artists who made extensive use of sampling in creating new music had an undisturbed ‘honeymoon’ period in the late 1980s and the very early 1990s when the record industry were caught unawares as to the potential for exploitation. Public Enemy voiced by the charismatic front man Chuck D, an artist with significantly controversial views on the laws regarding sampling and online music,13 were able to ‘run riot’ in this era without getting sued. Public Enemy produced their 1988 album ‘It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold For further reading on Chuck D’s controversial views on line music see: “The Noisy War Over Napster”, Newsweek, 5 June 2000 13 11 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Us Back’ which contained hundreds of samples without recognition in the album sleeve.14 Similarly, other groups such as N.W.A, the Beastie Boys, Ice Cube, De La Soul and Gang Starr 15, were all free to create albums of high critical acclaim using hundreds of un-cleared samples during this period, before the restrictive ruling in Grand Upright v Warner (1991)16 was decided. Although the big music companies had been caught unawares, they soon took notice of the potential of this technology for abuse by producers sampling their extensive back catalogues without permission. More money could be made from long forgotten artists whose popularity had dwindled, without increased expenditure. Hip hop instigated a sampling revolution and white corporate American wanted to cash in and contain black cultural expression. Sampling and copyright law clashed thus the record labels began to enforce their rights and drafted the lawyers in. Copyright: The Current Law “Thou shalt not steal.”17 When rapper Biz Markie sampled the melody from Gilbert O’ Sullivan’s 1972 hit ‘Alone Again (Naturally)’18 for his song ‘Alone Public Enemy, It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (Def Jam: 1988) N.W.A., Straight Outta Compton (Priority Records: 1989); Beastie Boys, Paul’s Boutique (Capitol/EMI Records: 1989); Ice Cube, Amerikkkas Most Wanted (Priority Records: 1990); De La Soul, 3 Feet High and Rising (Tommy Boy Records: 1989); Gang Starr, Step In The Arena (Noo Trybe Records: 1991). 16 Grand Upright v. Warner 780 F. Supp.182 (S.D.N.Y. 1991) 17 Exodus 20:15 18 Gilbert O’Sullivan, Alone Again (Naturally), on Himself (MAM 1972) 14 15 12 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Again’ on his 1991 album ‘I Need A Haircut,’19 Judge Kevin Thomas Duffy opened with this (un attributed) Biblical admonition from Exodus. Gilbert O’ Sullivan denied Biz Markie the right to use the sample but Biz Markie ignored this and Gilbert O’Sullivan filed suit. In his opinion, Judge Duffy likened Biz Markie to a common thief, granted an injunction against future distribution of the album and song, and referred the case to a U.S. district attorney for possible criminal prosecution. Although Biz Markie never served time for his alleged violation of the ‘Eighth Commandment,’ the case did set the precedent for viewing unlicensed sampling as a crime. 20 Unauthorised sampling is theft. If you want to be a jurisprudential purist about it then this three word sentence sums the technique up. 21 However, I know of no criminal convictions to date that have arisen because of a copyright violation from sampling. The majority of legal precedent regarding digital sampling stems from a discrete number of cases in the USA. In 1993 Jeremy J Beadle recognised the absence of English case law on copyright infringement. 22 The most likely case to reach the English courts was in 1989 concerning ‘The Beloved’ sampling “a mere eight notes” from a CD by Hyperion of compositions by medieval composer Abbess Hildegard of Biz Markie, Alone Again, on I Need A Haircut (Warner Bros inc/Cold Chillin’ 1992) Refer to note 15 supra. 21 Refer to note 7 supra at 197. 22 Refer to note 7 supra at 199. 19 20 13 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Bingen.23 The case reached a preliminary ruling in which the judge Hugh Laddie QC indicated he had ‘some sympathy’ with the defendant’s viewpoint and was prepared to let the case go on to full trial. However, it was the plaintiff who ended up backing down as the defendants were a much larger record label. Consequently, no legal precedent was set in the UK regarding whether the size of the sample was an issue. Twelve years on, little has changed. A quick search on Westlaw reveals precisely the same answer. In the UK, settling out of court is the norm in the music industry when a sample has been taken without permission. Although this case possibly offered some hope if it were to have proceeded to full trial, samplers in the UK are justifiably wary of English Courts blindly following the precedents set in the USA, preferring to settle out of Court rather than to litigate through to judicial decision which could prove very costly. In the United Kingdom, the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA 1988) regulate the copyright system. Copyright subsists in “original literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works” and in “sound recordings, films or broadcasts.” 24 Section 16 of ‘the Act’ confers upon J.Beadle refer to note 6 supra, Gothic Voices: A Feather on the breath of God: Sequences and Hymns by the Abbess Hildegard of Bingen (LP [Hyperion, 1984}; The Beloved, The Sun Rising (single) (East West, 1989) 24 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, section 1(1). 23 14 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story copyright owners five restricted, exclusive rights to control how, when or if their copyright works may be used.25 Musicians who sample from sound recordings produce what are known as secondary or derivative works defined in s. 5A(1)(b) of ‘the Act’ which stipulates a sound recording is: “a recording of the whole or any part of a literary, dramatic or musical work, from which sounds reproducing the work or part may be produced, regardless of the medium on which the recording is made or the method by which the sounds are reproduced or produced.” Therefore copyright would certainly subsist in parts of previous recordings which have been incorporated into the derivative work through sampling. However, if these songs are highly original in their own right and permission has been obtained and a fee paid to use the samples, then a sampler’s derivative work is granted a copyright of its own.26 If a fee has not been paid for a license to use the sample, then if the sampler attempts commercial exploitation of his derivative work he may breach copyright on up to three counts. Copyright subsists in ‘the song’ otherwise known as the ‘composition right’ which will usually be owned by the music publisher. Copyright also subsists in the recording, otherwise known as the ‘mechanical right’ which is usually These restricted acts include(a) to copy the work, (b) to issue copies of the work to the public, (ba) to rent or lend the work to the public, (c) to perform, show or play the work in public,(d) to communicate the work to the public and (e) to make an adaptation of the work or do any of the [above] in relation to an adaptation. 26 J.Davis, Intellectual Property Law, 2nd edition (London: Butterworths 2003) 106 25 15 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story owned by the record label that issued the recording. The third right can be seen as the moral right of an author (which always retain with the author and cannot be assigned as with the actions in s.16). 27 When a producer samples a record without obtaining permission, he is essentially breaching the composition and recording right. Section 16(3) of the CDPA 1988 qualifies the restrictions on the use of a work outlined in the section and described above, in that the ‘act’ done must be “in relation to the work as a whole or any substantial part of it.” It is this ‘substantial part’ qualification that provides the confusion due to a lack of UK case law on sampling. A current misconception by these producers is that if they sample a very small segment of a song, they will not be in breach. However, a ‘substantial part’ is defined qualitatively, not quantitatively. 28 The current test or consensus employed by producers on independent labels in the music industry is one of ‘recognition,’ however as Jeremy J. Beadle points out it, it is a defence as yet untested in the UK courts. 29 The large record labels generally insist that recognition is a collateral fact and that if any sample has been taken, it must be licensed. The misconception of what constitutes a sample is primarily because no case law has emerged on this subject from UK Courts. Producers and record labels have merely used the For further commentary on the moral right see below. NB: a further right may be in the lyrics to the composition however these are often usually both held by the copyright owner in the composition. 28 J.Davis supra note 9 at 117 in reference to Lord Pearce in Ladbroke (Football) Ltd v William Hill (Football) Ltd [1964] 1 All ER 465 29 Refer to note 8 supra, 78 27 16 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story American precedents as a warning not to proceed to trial because of the immense costs which they may potentially incur. Alternatively the large record labels who own extensive back catalogues which are sampled may not wish for an unfavourable precedent to be set in UK courts and a new definition of ‘substantial part’ vis a vis sampling as it may potentially see the lucrative market in sample clearance dry up.30 Because of the strict laws on copyright, producers attempt to find more and more obscure sources to sample from and distort in a move to make their sources unrecognisable, this is the common procedure DJ Shadow employs.31 DJ Premier uses less obscure sources: “I love Hendrix, but if I sampled him I would only use one of his drum beats or a hi hat, not a guitar riff. Obscurity is the best part.” 32 We can see from this that certain producers may see copyright law as a challenge and sampling a ‘game’ of sorts. The most recent (US) case law on sampling which attempted to clarify this grey area of the law is last year’s decision in Bridgeport Music v. Dimension Films . 33 The ruling focuses on the 1990 N.W.A song "100 Miles and Runnin'." 34 The track samples a three-note guitar riff from a 1975 Funkadelic track, "Get The Arts Law Centre of Australia: Music Sampling http://www.artslaw.com.au/reference/003music_sampling/ (accessed 25 February 2005) 31 I am referring to obscurity in relation to the labels that the recording was released on may have gone out of business and the artist dead or long forgotten. 32 Refer to note 13 supra at 172. 33 383 F. 3d 390 (6th Cir. 2004) 34 N.W.A., 100 Miles and Runnin, on Niggaz4Life (Priority Records: 1991) 30 17 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Off Your Ass and Jam." 35 The sample, in which the pitch has been lowered, is only two seconds long but is looped to extend to 16 beats and appears five times throughout the track. If an audio comparison is made, this sample is much more insignificant than the Biz Markie sample which made a greater use of the original sound recording which signifies the tightening of the law in this area and the vigilance of record labels who own the rights. At first instance, the court ruled that the sample "did not rise to the level of legally cognizable appropriation"36, which seemed a victory for samplers. However, on appeal from the plaintiffs, the higher court saw a more different view. They acknowledged that a “bright-line test” was needed for clarity in the music industry in what constituted an actionable infringement in digital sampling thus they questioned: “If you cannot pirate the whole sound recording, can you "lift" or "sample" something less than the whole. Our answer to that question is in the negative.” The case sets the current legal standpoint in the industry. It rejects any acceptance of fragmentary borrowings and supports fully a commercial licensing position. The law has sided with capitalist big business to the detriment of the creator. This decision was a damaging blow to samplers and stifled creativity even further. In protest, the antagonists at George Clinton Jr and the Funkadelics, Get Off Your Ass and Jam, on Let’s Take It To The Stage (Westbound Records: 1975) 36 Technician online: Sampling the future http://www.technicianonline.com/story.php?id=010041 (Accessed 15 January 2004) 35 18 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Downhillbattlle.org posted the Funkadelic sample on their website and invited people to remix it themselves.37 The Moral Right Dimension The concept of Moral Rights, peculiar to signatories of the Berne Convention 38 and contained in sections 77 to 79 of the CDPA 1988, adds another twist to the complex arrangement of copyrights that are possible in a musical work. Even when a composer has assigned all of the ‘economic’ rights conferred under s. 16 of the CDPA 1988 to a music publishing company, they still will retain the moral right of paternity and integrity. This enables the composer to prevent their music being used for particular works on moral, political or religious grounds for example. The rise of the internet has enabled music to be shared widely and easily thus on a home computer, an amateur may create a ‘mashup’ which is where two tunes of differing genres are mixed together to create a new sound. Artists may insist on their moral rights in this sense if a commercial release of these records are planned, although a lawyer representing record labels39 has stated that during his time spent dealing with sample clearance, it was very rare for an original composer of a musical work to insist upon their strict DownHill Battle, Music Activism: Three Notes and Runnin http://www.downhillbattle.org/3notes/ (Acessed 22 December 2004) 38 Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 1886 39 Refer to note 4 supra. 37 19 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law moral rights to oppose a release. Supervisor: Alan Story Even so, the situation could arise. A female artist may not wish to be sampled on a misogynist rap track or someone with strict religious views may not wish to be sampled on something they though was vile. Although I believe copyright laws are at present too harsh on musicians who sample, I can find no fault with the moral right of an composer not too see his work ‘butchered’ especially if it is used to mix with a genre of particular controversy such as gangsta-rap, the controversial sub genre of hip hop. Copyright Laws as a Barrier To New Talent The court in Bridgeport Music v Dimension Films did not think that their ruling would stifle creativity in any significant way. However this perhaps shows the judiciary’s ignorance towards as yet un established musicians who produce sample based music. The American legal precedents frighten record labels into rejecting many artists because of the extensive number of samples they use. Human Being, a British sample based musician acutely sums up these problems: “I have encountered many problems because of sampling, mainly it frightens labels... Humanity [album] got rejected several times because labels didn't want the hassle of clearing over 500 samples. Today I found that to even get a copyright/manufacturing license (to make my own 20 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story records) I have to clear all my samples, it's like I'm being forced to lie. I make music for fun, but sampling laws, and label hunting makes the whole process exhausting. It really isn't easy to make it, even if your expectations are small. sampling laws in general need much more clarity and there should be a more defined rules of "fair use". The laws right now are so stringent that your almost forced to break the law (especially if your an independent artist). It's a catch 22, if I had the money to purchase the instruments to create the sounds (or for that matter, the money to pay for the samples), I would, but I don't so the process of releasing a record is much more difficult.”40 This interview exemplifies the problems of an independent producer striving for commercial success. Copyright laws have a stranglehold over them as the financial demands it imposes for a legal release maintain that they may well reside in the underground for the duration of their career or may well be never to exploit their work commercially, being more of a hobby. The established sample based musicians in the industry at present are only established because they gained commercial success when sampling was not ‘regulated’ as such as it is today. An aspiring sample based producer will find it difficult if not impossible to secure a record deal today if they sample heavily. This interview directly shows the stifling of creativity that is The Beat Surrender,Online Music Magazine: Interview with Human Being http://www.thebeatsurrender.co.uk/interviews/human-being/ (Acessed 14 January 2005) 40 21 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story occurring under the surface. Copyright laws are too harsh and neglect the problems it causes to aspiring musicians attempting to succeed commercially. Fallacies in Sample Clearance The current sample clearance system is particularly prejudicial and financially oppressive. Producers who sample heavily may not have a problem if they have the backing of a large record label who are willing to pay to clear each and every sample they have used in their work. However, for a sampler on a small independent label or even for aspiring unsigned producers (such as Human Being above), the official route of sample clearance is unaffordable, time consuming and may cost more than the records are expected to recoup, especially if they have a limited pressing. Sample clearance will need to be achieved for every sample of which there could possibly be hundreds on an album therefore the process may take months to clear. Despite the lack of sample clearance on 3 Feet High and Rising, the Biz Markie decision meant the 1991 release of De La Soul is Dead had to be held back for several months as every sample was scrupulously cleared (and is thus every sample scrupulously credited in the accompanying album sleeve). 41 J.J. Beadle refer to note 6 supra , De La Soul: De La Soul is Dead (Tommy Boy Records: 1991) 41 22 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story The costs of clearing a sample and the methods used to determine them vary with the strength of the record label. A lump sum may be required or a lump sum and a percentage of the royalties. If the album is not a success then this can prove devastating to smaller record labels and the album may go into negative royalties such as Black Sheep’s 1991 release, A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing.42 An independent record label wary of poor record sales will see this as a barrier to obtaining clearance so may not seek it altogether. If sample clearance is not obtained in advance and the song is a success then 100% of the royalties may be lost to the uncleared sample’s copyright holders. The primary reasoning for this, regards the imbalance of bargaining power between the large record labels and the smaller independent labels or artists. This severely restricts an artist’s ability to negotiate a favourable deal when clearing a sample if they have little financial resources. Artists must not sample without obtaining permission and paying for every sample they use, or they face the cost of litigation in which the law’s favour of capitalism and the strict notions of ownership and authorship of intellectual property inevitably prevail. Agencies such as the MCPS 43 only offer a means for artists who sample to establish contact with music publishers and record labels however the 42 43 Refer to note 40 supra, Black Sheep, A Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing (Mercury Records 1991) Mechanical Copyright Protection Society: http://www.mcps.co.uk/. 23 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story ultimate negotiating is done between the labels themselves. This is not negotiation at all as the larger labels simply decide what price they wish to charge to grant a license to use the mechanical right in the sound recording.44 The independent labels or artists must ultimately simply accept this price (which can be up to ₤2000) or face the wrath of the company in litigation if they do not comply. As the antagonists at downhillbattle.org recognise: “Requiring artists to get authorization does not just put a hurdle in their way, it makes most sample based music impossible to create legally because of overwhelming financial and legal burdens.”45 This official, legally acceptable route remains a financially unviable option for the majority of artists not signed to one of the dominant players in the industry as they may utilise hundreds of sampled snippets throughout their recording and will need to ‘clear’ every one. The continued emergence of illegal ‘white label’ releases highlight this issue. Sample clearance is simply not an option for the smaller labels thus they continually break the strict laws of copyright. To ensure uniform legality through all tiers of the music industry, the sample clearance system needs to be revolutionised or discarded altogether. Original UK Hip Hop: A beginner’s guide to sample clearance http://www.ukhh.com/features/articles/twizt/5.html (Accessed 3 February 2005). 45 Refer to note 39 supra 44 24 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Solutions i) sample clearance The current sample clearance system is tailored to suit the larger companies in the music industry and is prejudicial for reasons outlined above. To insure legal conformity throughout the music industry, the current system must either be discarded altogether or the royalty payments regulated to an extent they are affordable and permission can be obtained swiftly. This may occur with placing a cap on the number of units that may be produced before sample clearance needs to occur however at present any commercial release is illegal without a license. ii) Royalty free-music and the Creative Commons Another option open to samplers who wish to commercially exploit their work without fear of infringing copyright is by using royalty free music. Discs specifically created for sampling can be obtained by certain companies who specialise in this field such as Zero-G. 46 In recent years, certain non profit organisations such as MACOS47 or Lawrence Lessig’s Creative Commons have also been setup primarily as a result of the growing criticism of strict laws on copyright as a barrier to creativity. Zero-G Digital Audio Samples http://www.zero-g.co.uk (Accessed 13th January 2004) Musicians Against Copyrighting of Samples http://www.icomm.ca/macos/ Accessed February 26 January 2005) 46 47 25 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story The Creative Commons offer a licensing system for creators to easily adopt and tag works which may be freely sampled as well as providing a search utility for potential users to find the music to sample.48 It is a form of preemptive licensing where creators keep their copyright but license certain rights of use to the individual by adopting one of three types of license on a sliding scale. By using a Creative Commons licensed source, samplers may find it easier to legally release their work. Creators may also benefit and see a dramatic increase in fees obtained by licensing, and may also receive notoriety and a possible new revenue stream. As such, the Beastie Boys who are prolific samplers themselves have released their own music under a Creative Commons license for users to freely remix and they have received media attention as a result.49 However, I cannot see that the Creative Commons license is a big enough step at present for musicians who sample. Part of the culture involved in sampling is by searching through dusty crates of old records, not just remixing new music. For the license to be fully effective a significant number of recording artists have to grant permission to sample under the ‘SamplingPlus licence’ which permits commercial use of the work.50 It may also be difficult to get older copyrighted works participating in the license scheme. Creative Commons: Sampling Licenses http://creativecommons.org/license/sampling?format=audio 49 Wired Magazine: Creative Commons and Sampling http://wired.com/wired/archive/12.11/sample (Accessed 26 January 2005) 50 Refer to note 51 supra : Although the Beastie Boys, Chuck D and David Byrne all have released songs under a Creative Commons License and received media attention, all of these tunes still denied the user the right to commercially exploit the work. 48 26 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Without a wide variety of material available, from old sources, samplers will be put off by this deficiency. As attractive as it may sound, the Creative Commons is not a viable solution for musicians who sample from old records. iv) don’t sample? Many musicians today prefer not to sample at all. After a series of cases in the USA during the 1990s which began with the Biz Markie decision, many artists turned their back on sampling the work of others for fear of losing their own royalty payments to cover the clearance of samples. Although this promotes creativity to create entirely new musical works it has significantly affected the sound of hip hop music which has lost the essence of funk and soul it once had. Copyright laws and judicial interpretations of them, were instrumental in changing the sound of the genre altogether. Alternatively, musicians such as Dr Dre, wary of the high costs of clearing the rights of the record labels in the sound recording, opted instead to interpolate the work. That is to say these musicians brought live musicians into the studio to replicate the sound on the recording. In this way, costs were minimised as only the composition rights had to be cleared. 27 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story iii) blanket licensing The current sample clearance system needs to change. Although none of these solutions are fully workable, a blanket license would mean that producers who use samples would pay an annual license fee to the MCPS who would distribute royalties to the composers and record labels used. A similar blanket license exists when works are played or shown in the media. The Performing Rights Society 51 grant a blanket license to television and radio producers to use music in their programmes and a blanket licensing system could be a possible option. However, when moral rights are taken into consideration the argument for such a scheme loses weight. Conclusions The war on unauthorised sampling epitomises the contemporary clash in intellectual property between the capitalist preservation of the fiscal value of intellectual property in the notions of authorship and ownership, and the conflicting view that the strict grasp of these notions stifle creativity and expression. Law makers suggest the raison d’etre of intellectual property laws are to protect the economic interests of creators from un-licensed exploitation. By doing so the laws exist as an incentive to create but paradoxically in the post-modern era of digital sampling, this is precisely what they are inhibiting. 51 Performing Rights Society: http://www.prs.co.uk/ (Accessed 27 February 2005) 28 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story The law is outdated and should embrace the change in popular culture rather than inadvertently treat it with such abhorrence by the exploitation of the industry who use it as their shield. Time is ripe for either a statutory amendment to define ‘substantial part’ in relation to sampling, or a judicial interpretation of this ambiguous term. A change is needed to embrace and recognise the shift in popular culture and contemporary techniques in music production, present in our world today. The law needs clarification and a compromise needs to be achieved for the good of contemporary music and its continued development. 29 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Bibliography Statutes & Instruments Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 1886 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Cases Bridgeport Music v. Dimension Films 383 F. 3d 390 (6th Cir. 2004) Grand Upright v. Warner 780 F. Supp.182 (S.D.N.Y. 1991) Ladbroke (Football) Ltd v William Hill (Football) Ltd [1964] 1 All ER 465 Articles S.Frith, Art versus Technology: The Strange Case of Popular Music, 8 Med., Culture & Soc’y 263, 275 (1986) D. Sanjek, ‘”Don’t Have To DJ No More”: Sampling and the “Autonomous” Creator, (1992) 10(2) Cardozo Arts and Entertainment Law Journal 607, 612. 30 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story M. Stevens ‘How record labels have used intellectual property rights to obtain a dominant hold on the global market and the potential role parallel importing, anti-competition law and on-line distribution have in breaking this.’ Kent Law School Intellectual Property Law Dissertation April 2002 https://www.kent.ac.uk/law/undergraduate/modules/ip/resources/ip_dissert ations/Diss-Stevens.doc (Accessed February 26 2005) “The Noisy War Over Napster”, Newsweek, 5 June 2000 Books J.J.Beadle, Will Pop Eat Itself? Pop Music in the Soundbite Era(London: Faber and Faber Ltd. 1993) 79 Christie A and Gare S (eds), Statutes on Intellectual Property Law, 7th edition, 2004, Blackstones. J.Davis, Intellectual Property Law, 2nd edition (London: Butterworths 2003) Alan Light (ed), The Vibe History of Hip Hop (New York: Three Rivers Press 1999), 170 31 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Judy Pearsall (ed), Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 10th edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2002) S.Vaidhyanathan “Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How It Threatens Creativity”, New York University Press, New York 2003. Websites The Arts Law Centre of Australia: Music Sampling http://www.artslaw.com.au/reference/003music_sampling/ (accessed 25 February 2005) The Beat Surrender,Online Music Magazine: Interview with Human Being http://www.thebeatsurrender.co.uk/interviews/human-being/ (Accessed 14 January 2005) Creative Commons: Sampling Licenses http://creativecommons.org/license/sampling?format=audio CD Baby Independent Music: Future of Music Coalition - Future of Music Summit May 3rd 2004 http://www.cdbaby.net/fom/000013.html (Accessed 18 February 2005) 32 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Duke University School of Law: Music and Theft: Technology, Sampling and The Law. Video presentation, Panellist 1 of panel 1: Anthony Kelley at: 00:05:39 http://realserver.law.duke.edu/ramgen/musicandtheft2002/musicpanel1.rm DownHill Battle, Music Activism: Three Notes and Runnin http://www.downhillbattle.org/3notes/ (Accessed 22 December 2004) Mechanical Copyright Protection Society: http://www.mcps.co.uk/. Musicians Against Copyrighting of Samples http://www.icomm.ca/macos/ Accessed February 26 January 2005) Original UK Hip Hop: A beginner’s guide to sample clearance http://www.ukhh.com/features/articles/twizt/5.html (Accessed 3 February 2005). Performing Rights Society: http://www.prs.co.uk/ (Accessed 27 February 2005) Technician online: Sampling the future http://www.technicianonline.com/story.php?id=010041 (Accessed 15 January 2004) 33 Richard Harrison Intellectual Property Law Supervisor: Alan Story Wired Magazine: Creative Commons and Sampling http://wired.com/wired/archive/12.11/sample (Accessed 26 January 2005) Zero G Digital Audio: About Copyright and Sample CDs http://www.zerog.co.uk/index.cfm?articleid=39 (Accessed 14 December 2004) 34