molecular phylogenetic analysis of grifola frondosa (maitake)

advertisement

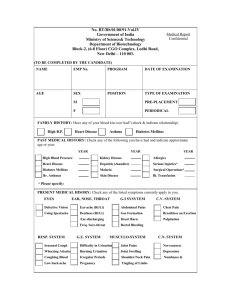

Mushroom Biology and Mushroom Products. Sánchez et al. (eds). 2002 UAEM. ISBN 968-878-105-3 MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF GRIFOLA FRONDOSA (MAITAKE) REVEALS CRYPTIC NORTH AMERICAN AND ASIAN SPECIES Q. Shen, D. M. Geiser and D. J. Royse Department of Plant Pathology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802 <djr4@psu.edu> ABSTRACT A phylogenetic analysis was performed on 51 isolates of the commercially valuable Grifola frondosa (maitake) using sequences from the Internal Transcribed Spacers and 5.8S region of the nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA) transcriptional unit and a portion of the -tubulin gene. The betatubulin gene provided more than twice as much phylogenetic information as the ITS/5.8S regions. The isolates analyzed comprised 21 from North America, 27 from Asia, one from Europe, and two of unknown geographic origin, one of which was the major US commercial production strain in use. G. sordulenta was used as an outgroup. Combined and separate analysis of both genes showed a partition separating Asian versus North American isolates. Bootstrap analysis showed strong support for these clades in the beta-tubulin data alone and in the combined data. The major commercial isolate of unknown geographic origins apparently of Asian decent based on grouping within the Asian clade. The single European isolate analyzed was distinct from both the North American and Asian clades. These results indicate strong support for a cryptic species partition separating North American and Asian isolates of G. frondosa, despite previous studies indicating no morphological distinction between them. INTRODUCTION Grifola frondosa (Dickson: Fr.) S.F.Gray is a white rot fungus widely distributed in Asia, North America and Europe. It occurs on a variety of hardwoods, particularly oak and chestnut. Commonly called maitake or hen-of-the-woods, it is considered a choice edible mushroom with unique culinary and medicinal qualities. Maitake is marketed throughout Asia and, because of increased consumer demand, its commercial production has grown dramatically in Asia and the United States (Royse 1997, Chang 1999). Traditional classification of G. frondosa was based solely on morphological characters. Grifola frondosa was first named Boletus frondosus by Dickson (1785) and later, Fries (1821) changed the name to Polyporus frondosus Dicks.: Fr. Even now, P. frondosus, the synonym of G. frondosa, is widely used. The genus Grifola S.F.Gray was first applied by Gray (1821) and described as a polypore with large compound basidiomes. Previous taxonomic investigations by Gilbertson and Ryvarden (1986) and Zhao and Zhang (1992) described similar morphological characters shared between North American and Asian isolates, although these studies separately analyzed North American and mainland China isolates, respectively. Both studies recognized G. frondosa (Dicks.:Fr.) S.F.Gray as the only species in the genus Grifola. However, another Grifola species, G. sordulenta, was identified by Singer in 1969. Biogeographic phylogenetic structure is known to exist in various polypores and agarics, such as Pleurotus spp (Vilgalys and Sun 1994), Lentinula spp (Thon and Royse 1999, Hibbett et al. 1998). A better understanding of the biogeographic phylogenetic structure of G. frondosa may facilitate genetic selection and improvement of cultivated isolates in commercial mushroom production. Molecular approaches have been used extensively for examining phylogenetic relationships in other 73 edible fungi (for example see Hibbett et al. 1995, Thon and Royse 1999 and Vilgalys and Sun 1994). Recent studies by Hibbett et al. (2000) based on mitochondrial and nuclear small and large subunit ribosomal RNA sequences showed that G. frondosa is related to other polypores including Laetiporus and Ganoderma. To analyze biogeographic structure within G. frondosa, partial regions of rDNA and -tubulin genes were analyzed and phylogenetic relationships were inferred among isolates from North America and Asia. Results showed a strongly supported partition separating isolates from North America and Asia, suggesting that these represent separate species. MATERIALS AND METHODS Cultures. A total of 51 isolates of G. frondosa and one isolate of G. sordulenta were used in this study (Table 1). The isolates of G. frondosa included all available isolates from the Pennsylvania State University Mushroom Culture Collection (PSUMCC) and the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), as well as an isolate of G. sordulenta (Argentina) used as an outgroup. Isolates represented various geographic origins including Asia (27), United States (21), Europe (1), and unknown origin (2). All cultures were maintained on potato dextrose agar supplemented with 1.5g/L of yeast extract (PDYA). Table 1. List of species, isolate code, source, geographic origin, substrate and locality of Grifola frondosa used for this study. Source a Geographic origin Host/Substrate Locality G. frondosa Isolate code WC248 L.C. Schisler PSU, PA N/A b N/A G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa WC364 WC367 WC483 WC493 WC555 WC556 WC557 WC581 WC582 WC583 WC659 WC685 WC808 WC828 WC834 L.C. Schisler Jodon ATCC 11936 ATCC 48141 Y.H.Park Y.H.Park Y.H.Park Y.H.Park Y.H.Park Y.H.Park Y.H.Park B.W.Yoo Bill Shanley D.J.Royse NGF 001 N/A N/A Oak stump Quercus robur N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A White Oak Commercial isolate Castanopsis spp. N/A Hort. Woods N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Lowlands G. frondosa WC835 Hokken M-1 PSU, PA PSU, PA Maryland Norway Korea Korea Korea Korea Korea Korea Korea N/A Tidioute, PA N/A Nara Prefecture, Japan Japan Highlands G. frondosa WC836 Mori 51 Japan G. frondosa M001 USDA FP-101988-T Cooksville (Rock), WI G. frondosa M002 USDA FP-102464-Sp Madison, WI G. frondosa M003 USDA FP-102464-T Madison(Dane), WI G. frondosa M004 USDA FP-103424-T Athens(Georgia), GA Commercial isolate on oak Commercial isolate on oak Soil near downed hardwood log (Quercus?) Quercus, soil at base of dead stump. Quercus, soil at base of dead stump. Quercus nigra, at base Species 74 Highlands Edge of Old Mill Pond at Hwy 59, Fire #638 N/A Picnic Point, UW campus N/A Source a Geographic origin Host/Substrate Locality G. frondosa Isolate code M005 USDA FP-105867-Sp Beltsville (Prince George), MD G. frondosa G. frondosa M006 M007 USDA FP-134675-Sp USDA FP-47462 Madison (Dane), WI WV Quercus coccinea (scarlet oak) living, at base Quercus, underneath Quercus alba (white oak) G. frondosa G. frondosa M008 M009 USDA RLG-6889-Sp USDA LOO-14980-T Syracuse, NY LA Forest Disease Lab Station, Agr. Res. Center UW Arboretum Plat #55, at 1500 feet elevation, Devil's Hole N/A N/A G. frondosa M010 USDA OKM-4954-T G. frondosa M011 G. frondosa M012 USDA OKM-6133Sp USDA RLG-14995-T Beltsville (Prince George), MD Washington(District of Columbia), DC Baton Rouge, LA G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa M013 M014 M015 USDA L-15552-Sp USDA RLG-6889-T USDA TJV-93-130-T Syracuse, NY Syracuse, NY Madison(Dane), WI G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa G. frondosa M016 M017 M018 M019 M020 M021 M029 M030 M031 M032 M033 M034 M035 M036 M037 M038 M039 FIRDI 36283 FIRDI 36286 FIRDI 36355 FIRDI 36356 FIRDI 36357 FIRDI 36434 PSUMCC 600 PSUMCC 601 PSUMCC 602 PSUMCC 604 PSUMCC 630 PSUMCC 644 USDA RLG-6889-Sp X.W.Chen X. W.Chen ATCC 60891 Tan 0206 Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Taiwan Syracuse, NY China China China He Bei, China Species Quercus alba Quercus snag, inside of hollow (oak) N/A N/A Quercus virginiana N/A Quercus alba Quercus macrocarpa, base of live N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Commercial strain Commercial strain Commercial strain Commercial strain Commercial strain Commercial strain Quercus alba N/A N/A N/A N/A Ground, Beltsville Expt Forest Rock Creek Park Memorial Grove, LA State U campus N/A Oakwood Cemetery Turville Pt. Woods N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A Oakwood Cemetery N/A N/A N/A N/A G. frondosa M40 M. Chen China Commercial strain N/A G. G01 ATCC 200416 Argentina Nothofagus dombeyi N/A sordulenta trunk a ATCC = American Type Culture Collection; USDA = The Unitied States Department of Agriculture; FIRDI = Food Industry Research and Development Institute, Taiwan; PSUMCC = Pennsylvania State University Mushroom Culture Collection. b N/A = not available. DNA extraction. Cultures were grown in 50 ml of potato dextrose yeast broth (PDYB) for 20 to 30 days at room temperature. Mycelium was harvested by vacuum filtration on Whatman (grade #1) filter paper, and washed once with distilled water. Fresh mycelium (100 mg) was used to isolate DNA following the LETS extraction procedure (Chen et al. 1999). DNA preparations were diluted with sterile water and used as template for PCR amplification. PCR amplification and sequencing. PCR was performed in 25 µl reactions with a 96-well PCR cycler (PTC-100 Programmable Thermal Controller, MJ Research, Inc.), using 10ng DNA template, one U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI), 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 2 mM MgCl 2, 0.1% Triton, and 0.5 µM of each primer. Amplification of ITS-1, ITS-2, and 5.8 S rDNA was performed by utilizing primers ITS1AF (5'-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3') (White et al. 1990) 75 and ALR0 (5'-CATATGCTTAAGTTCAGCGGG-3') (RJ Vilgalys, personal communication). PCR reactions for ITS regions were performed using the following parameters: 94C/1 min; 35 cycles of 94C/15 s, 60C/30 s, 72C/1 min; and 72C/5 min. PCR Reactions for -tubulin regions were performed with primer BTG5F (5'-CGTTGTGCCCAGTCCTAAGGTG-3') and BTG8R (5'GTTCTTGCTCTGCACGTTCTG-3') (Figure 1) with the following parameters: 94C/2 min; 35 cycles of 94C/15 s, 57C/30 s, 72C/1 min; and 72C/7 min. Amplification products were electrophoresed on a 1.0% agarose gel and checked to ensure that a single DNA band was produced of the expected size (~600bp for ITS PCR products and ~680bp for -tubulin PCR products). For sequencing, the PCR products were purified directly from reactions using the Wizard PCR Preps System (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) and the concentration adjusted to 20ng/l. Sequencing reactions were performed using an ABI dye-terminator kit (ABI/Perkin-Elmer) and analyzed using an ABI Prism® Model 377 automated sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). BTG5F 5 6 7 8 BTG8R Figure 1. Locations of primers used for PCR-amplification of the -tubulin gene in Grifola frondosa and G. sordulenta (G01). Numbers indicate exons. Sequence data analysis. Sequence ends were trimmed using the SeqMan II module in the Lasergene package (DNAStar, Inc. Madison, WI) and adjusted manually. All sequences then were edited and initially aligned using the clustal W algorithm (Higgins et al. 1991) in the Lasergene package (DNAStar, Inc. Madison, WI). Multiple alignment parameters used were gap penalty = 10 and gap length penalty = 10. Final alignments then were optimized visually. Intron/exon junctions in the beta-tubulin sequences were inferred based on comparisons with the known Schizophyllum commune sequence (Russo et al. 1992). Levels of molecular sequence divergence in each of the data sets were compared by calculating pairwise estimates of nucleotide substitution rates by the two-parameter method of Kimura. Phylogenetic analyses were completed using PAUP Version 4.0b4a (Swofford 2000). A neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed using the Kimura 2parameter model. The stability of clades was evaluated by bootstrap tests with 1000 replications (Felsenstein 1985, Hills and Bull 1993). A maximum parsimony (MP) analysis was performed using heuristic searches with 1000 random addition searches. Other indices for the generated topology, including tree length, consistency index (CI), and retention index (RI) were calculated. A strict consensus of the minimum length MP trees was calculated. Gaps were considered missing data for all analyses. RESULTS Analysis of rDNA ITS sequences Amplification of the ITS-1, ITS-2 and 5.8S ribosomal DNA repeat yielded fragments of approximately 600bp as estimated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Characteristics of nucleotide variation present in these regions of G.frondosa and its allies are summarized in Table 2. Nucleotide variation among isolates of G. frondosa was 5.4% in the rDNA region, and 14.3% between G. frondosa and the G. sordulenta outgroup. 76 Table 2. Site variation within the ITS-1, 5.8 S, and ITS-2 gene region of Grifola frondosa and Grifola sordulenta. ITS-1 Isolates Number a variable sites Total sites G. frondosa 51 7 199 G. frondosa + 52 30 199 G. sordulenta. e a Number of isolates included. 5.8S Sites Total 0 158 0 158 ITS-2 Sites Total 24 217 52 217 Total Sites Total 31 574 82 574 A Neighbor-Joining analysis based on rDNA ITS sequences identified two clades within G. frondosa. The North American clade included all of the U.S. isolates, while the Asian clade consisted of Asian isolates. The North American clade received 83% bootstrap support, but the Asian clade did not receive >50% support. The single European isolate (WC493) fell on a branch basal to the North American clade, but its connection to this clade was not strongly supported (67%). Two isolates of unknown geographic origin (WC685 and WC828, the major US commercial isolate) were placed within the Asian clade. The maximum parsimony (MP) analysis produced 424 equally parsimonious trees (length = 113 steps, consistency index=0.796, retention index=0.911), which were similar in topology to the neighbor-joining tree. Analysis of -tubulin sequences The characteristics of nucleotide variation present in partial -tubulin sequence regions of G. frondosa and G. sordulenta are summarized in Table 3. Among isolates of G. frondosa, nucleotide variation was 12.2% for all sites. Most of the variation occurred in introns with 14.8% for intron 5, 23.7% for intron 6, and 32.3% for intron 7. Less variation was observed in exons with 8.3% for exon 6 and 5.5% for exon 7. The sequences of G. frondosa and G. sordulenta showed much more variation over the total alignment (30.2%) and across the introns and exons. The most variable region was intron 5 (56.9%) and exon 7 was the most conserved region (18.3%) within the tubulin gene sequence regions analyzed. No amino acid changes were inferred among isolates of G. frondosa, but two amino acid changes (Glutamate and Isoleucine in G. frondosa, but Glutamine and Valine in G. sordulenta, both in exon 6) were observed between isolates of G. frondosa and G. sordulenta. Most nucleotide substitutions in exons were observed in the third codon positions. Table 3. Site variation within the partial -tubulin gene region of Grifola frondosa and Grifola sordulenta. Exon 5 Isolates G. frondosa G. frondosa + G. sordulenta number 51 52 a variable sites 0 0 Intron 5 Total sites 4 4 Sites 8 33 Exon 7 Isolates number G. frondosa 51 G. frondosa + 52 G. sordulenta a Number of isolates included. Sites 9 30 Total 54 58 Intron 7 Sites Total 20 62 33 62 Total 164 164 Exon 6 Sites 19 45 Total 229 229 Exon 8 Sites Total 1 8 1 8 Intron 6 Sites 14 35 Total 59 62 Total Sites Total 71 580 177 587 A Neighbor-Joining analysis based on partial -tubulin gene sequences gave similar results to those based on the rDNA dataset, showing two distinct North American and Asian clades within G. frondosa. The North American clade received 99% bootstrap support, whereas the Asian clade received 74% support. In contrast to the rDNA tree, where the European isolate grouped basal to 77 the North American clade, the beta-tubulin tree placed the European isolate (WC493) on a branch basal to the American clade, with 95% bootstrap support. As in the rDNA analysis, the two isolates of unknown geographic origin grouped with the Asian isolates. The maximum parsimony (MP) analysis produced 48,100 trees (length=251 steps, consistency index=0.793, retention index=0.932) until PAUP was aborted because of lack of memory. The strict consensus of these trees was similar in topology to the neighbor-joining tree. A phylogenetic analysis without intron 5 was also performed because of the high variation in this region. No appreciable difference was found (data not shown). Analysis of combined rDNA ITS and partial -tubulin gene sequence data A Neighbor-Joining analysis (Figure 2) based on combined rDNA ITS and partial -tubulin gene sequence data supported most of the results produced by rDNA and -tubulin separately, with much higher bootstrap support. The North American and Asian clades were strongly supported by high bootstrap values (100% and 98%, respectively). The European isolate (WC493) was grouped basal to the Asian clade with 89% bootstrap support, and agrees with the results from the -tubulin data alone. The two isolates of unknown geographic origin (WC828 and WC685) grouped within the Asian clade. The maximum parsimony (MP) analysis, based on combined dataset produced 405 equally parsimonious trees. The strict consensus tree (not shown, length=382 steps, consistency index=0.741, retention index=0.901) retained a similar topology, for the most part, to the NJ trees. DISCUSSION The 51 isolates of G. frondosa analyzed in this study clearly clustered into two clades based on North American and Asian origins in all analyses of rDNA, -tubulin, and combined sequences. Six simplified trees were shown in Figure 3 (A-F). This result conflicts with previous taxonomic studies indicating no appreciable morphological differences between North American and Asian isolates (Gilbertson and Ryvarden 1986, Zhao and Zhang 1992), which included descriptions of basidiomes, basidiospores, habitats and hyphal context systems. However, neither study compared North American and Asian isolates side-by-side. No mating tests between the North American and Asian isolates have been conducted to determine if they are different biological species. Investigations of mating compatibility between North American and Asian isolates of G. frondosa may uncover an intrinsic reproductive barrier separating these groups. The name Grifola frondosa (Dicks.) Gray was applied to the basionym Boletus frondosus J. Dicks., which was described based on a specimen collected in England (Dickson 1785, Gray 1821). Although only a single, non-type European isolate was analyzed in the current study, the phylogenetic data suggest the possibility that a distinct European lineage may exist in G. frondosa. If this is the case, then phylogenetic taxonomic revisions would require that the name G. frondosa be applied to the European lineage, with different names for the North American and Asian clades. Taxonomic changes must await study of the type material and an expanded sampling of isolates from Europe and the British Isles. 78 Geographic origin WI M001 NY M008 DC M011 PA WC808 LA M012 NY M014 NY M035 LA M009 NY 81 M013 WI M002 PA WC364 WI M015 WI M003 GA WI M004 MD M006 100 PA M005 MD WC367 WV WC483 MD M007 PA M010 81 WC248 Taiwan Taiwan M016 Taiwan M017 Taiwan M018 Taiwan M031 Japan M020 Taiwan WC836 Taiwan M029 Korea M033 China WC659 China M036 N/A M037 Japan WC828 Korea WC835 82 Korea WC581 Korea WC556 Korea WC557 Taiwan WC582 Taiwan M030 Taiwan M032 China Korea M034 M040 Japan China WC583 98 China WC834 N/A M038 Korea M039 89 Taiwan WC685 Taiwan WC555 100 Norway M019 M021 WC493 G. sordulenta G01 ITS+-tubulin NJ 0.005 changes I. U.S. II. Asia Europe Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of 51 Grifola frondosa isolates. Based on a combination of rDNA and partial -tubulin gene sequences using the neighbor-joining method with distance analysis calculated by the Kimura 2-parameter model. Geographic origin is shown beside isolate codes. Numbers on branches represent bootstrap values obtained from 1,000 replications (values greater than 80% were shown). Sidebars represent inferred clades based on geographic origin. 79 We analyzed only a single isolate from Europe (WC493) and its phylogenetic relationship to other isolates is not clearly resolved. G. frondosa is common in Europe (Breitenbach and Kränzlin 1986), but this was the only culture readily available for this study. The beta-tubulin analysis and combined analysis both showed WC493 to form a distinct basal branch related to the Asian clade. However, because most of the phylogenetically informative sites came from the -tubulin sequence, this inferred relationship between WC493 and the Asian clade cannot be considered strong (Table 4). Because the single European isolate analyzed did not show a strong relationship either to the North American or Asian clades, a third, European clade may exist whose discovery awaits the study of more isolates. Further study of Grifola spp and relatives from the Southern Hemisphere also may uncover additional interesting biogeographic patterns. Continental phylogeographic structure is common in basidiomycete macrofungi. Intersterility groups in the Pleurotus ostreatus species complex correlate well with continental biogeography, and also with an ITS rDNA phylogeny (Vilgalys and Sun 1994). Phylogenetic partitions may exist that do not correlate with intersterility barriers. In Lentinula edodes (shiitake), strong continental phylogeographic structure is evidenced based on rDNA phylogenies, including fairly distinct Asian and North American clades (Hibbett et al. 1995, Hibbett et al. 1998). Our results are consistent with the proposal that a biogeographic connection exists between basidiomycete macrofungi from eastern Asia and temperate North America (Wu and Mueller 1997). In the genus Suillus, this observation is supported by the inference that North American species tend to have closely related Asian sister taxa, based on ITS rDNA data (Wu et al. 2000). The split-gill fungus Schizophyllum commune shows worldwide interfertility and a limited degree of phylogeographic structure in its cosmopolitan range (Raper et al. 1958, James et al. 1999, James et al. 2001). Table 4. Summary of sequence alignments a of rDNA, -tubulin and combined datasets for Grifola frondosa. rDNA Total nucleotide (nt) sites Variable nt sites Phylogenetically informative nt sites a 574 82 25 -tubulin 587 177 62 (37 in introns) Combined 1161 259 87 Alignments including 51 sequences of G. frondosa and G. sordulenta. Multilocus phylogenetics provides a powerful tool for the recognition of species, as phylogenetic partitions shared among different loci indicate a historical reproductive barrier between clades (= genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition or GCPSR, Taylor et al. 2000). The shared partition between Asian and North American isolates indicated by both genes indicates a reproductive barrier between these groups, meeting the criteria of GCPSR. However, we cannot say whether the reproductive barrier is intrinsic (i.e., reflecting intersterility) or extrinsic (i.e., reflecting geographic separation). Because phylogenetic partitioning can precede the evolution of intersterility, it cannot be assumed that Asian and North American isolates of G. frondosa are intersterile. Indeed, strong geographic and phylogenetic partitions, albeit inferred from single genes, can be observed within intersterility groups in the genus Pleurotus (Isikhuemhen et al. 2000, R. Vilgalys, personal communication), and, despite worldwide interfertility (Raper 1958), some degree of continental biogeographic structure can be found in the split-gill fungus Schizophyllum commune (James et al. 1999, James et al. 2001). It is expected that recombination occurs among isolates within the two geographic lineages of G. frondosa, but evidence for that cannot be extrapolated from these data. Neither the beta-tubulin nor the ITS rDNA trees show much strongly supported structure within lineages, and the partition homogeneity test (PHT) or incongruence length difference (ILD) test cannot be applied to these datasets because of relatively high levels of homoplasy (Farris et al. 1995, Koufoupanou et al. 1997, Barker and Lutzoni 2000). 80 100 99 U.S. 83 U.S. U.S. 67 98 74 WC828 Asia WC828 Asia WC493 Europe 95 89 WC493 Europe WC493 Europe G. sordulenta A Combined/NJ G. sordulenta G. sordulenta B -tubulin /NJ 97 97 WC828 Asia C rDNA/NJ U.S. U.S. U.S. 52 84 WC828 Asia 74 WC828 Asia 91 61 WC828 Asia WC493 Europe WC493 Europe WC493 Europe G. sordulenta G. sordulenta G. sordulenta D Combined /MP One of 405 MP trees Length=382 steps CI=0.741, RI=0.901 E -tubulin /MP One of 5000 MP trees length=251 steps, CI=0.793, RI=0.932 F rDNA/MP One of 424 MP trees length = 113 steps CI=0.796, RI=0.911 Figure 3. Phylogenetic analysis of 51 Grifola frondosa isolates. Based on rDNA ITS (C and F), -tubulin (B and E) and combined (A and D) datasets using the neighbor-joining method (D, E and F) with distance analysis calculated by the Kimura 2-parameter model and maximum parsimony method (D, E and F). Numbers on branches represent bootstrap values obtained from 1,000 replications. 81 Both neighbor joining (NJ) and most parsimonious (MP) trees derived from all DNA datasets revealed a consistent grouping of U.S. commercial cultivar WC828 in the Asian clade (Figure 3). This suggested that WC828 has an Asian origin and is closely related to Asian commercial cultivars. It is known that molecular data can be effectively used to select unique shiitake genotypes for evaluation of biological efficiency, quality and average weight of mushrooms (Diehle and Royse 1986, Levanon et al. 1993). So, a better understanding of the phylogenetic relationships of G. frondosa may help the selection and breeding of commercial lines and help to improve commercial cultivation of these mushrooms. The beta-tubulin gene region provided more than twice as many phylogenetically informative nucleotide sites as did the ITS rDNA region, in a similar-sized amplicon. This result is consistent with findings in other fungi (e.g., O’Donnell 2000) and shows that beta-tubulin may be a more powerful tool for analyzing the intraspecific phylogeography of basidiomycete macrofungi than ITS rDNA. Other partial protein-coding genes such as translation elongation factor 1- may also be extremely useful. REFERENCES Chang, S.T. 1999. World production of cultivated edible and medicinal mushrooms in 1997 with emphasis on Lentinus edodes(Berk.) Sing. in China. Intenational J. med. Mushrooms 1:291-300. Chen, X., C.P. Romaine, M.D. Ospina-Giraldo and D.J. Royse. 1999. A polymerase chain reaction-based test for the identification of Trichoderma harzianum biotypes 2 and 4, responsible for the worldwide green mold epidemic in cultivated Agaricus bisporus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotech 52:246-250. Dickson, J. 1785. Fasciculus Plantarum Crytogamicarum Britanniae. Londini: Nicol. Diehle, D.A and D.J. Royse. 1986. Shiitake cultivation on sawdust: evaluation of selected genotypes for biological efficiency and mushroom size. Mycologia 78:929-933. Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783791. Fries, E. M. 1821. Systema Mycologicum: Sistens Fungorum Ordines, Genera et Species, Huc U.S.que Cognitas, Quas ad Normam Methodi Naturalis Determinavit, Disposuit Atque Descripsit. Lundae : ex officina Berlingiana. 355. Gilbertson, R. L and L. Ryvarden. 1987. North American Polypores. Fungiflora, Oslo, Norway. 332-333. Gray, S. F. 1821. A natural arrangement of british plants, according to their relations to each other as pointed out by Jussieu, De Candolle, Brown, and C including those cultivated for use, with an introduction to botany, in which the terms newly introduced are explained. Baldwin, Cradock and Joy, London. 643. Hibbett, D. S, L.B. Gilbert and M.J. Donoghue. 2000. Evolutionary instability of ectomycorrhizal symbioses in basidiomycetes. Nature 407:506-508. Hibbett, D. S., Y. Fukumasa-Nakai, A. Tsuneda and M.J. Donoghue. 1995. Phylogenetic diversity in shiitake inferred from nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycologia 87:618-638. Higgins, D.G, A.J. Bleasby and R. Fuchs. 1991. CLUSTAL W: improved software for multiple sequence alignment. CABIOS 8:189-191. Hills, D.M. and J.J. Bull. 1993. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Syst Biol 42:182-192. Levanon, D, N. Rothschild, O. Danai and S. Masaphy. 1993. Strain selection for cultivation of shiitake mushrooms (Lentinus edodes) on straw. Bioresource Tech 45:9-12. Royse, D. J. 1997. Specialty mushrooms and their cultivation. Hort Rev 19:59-97. Singer, R. 1969. Mycoflora Australis. Lehre: Cramer. 382-383. Swofford, D. L. 2000. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), 4.0b4a. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. Taylor, J.W, D.J. Jacobson, S. Kroken, T. Kasuga, D.M. Geiser, D.S. Hibbett and M.C. Fisher. 2000. Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi. Fungal Gen Bio 31:21-32. Thon, M.R. and D.J. Royse. 1999. Evidence for two independent lineages of shiitake of the Americas (Lentinula boryana) based on rDNA and -tubulin genes sequences. Mol Phylogen Evol 13:520-524. 82 Vilgalys, R. and B.L. Sun. 1994. Ancient and recent patterns of geographic speciation in the oyster mushroom Pleurotus revealed by phylogenetic analysis of ribosomal DNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:4599-4603. White, T., T. Bruns, S. Lee, and J. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis et al. (ed.) PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, New York. 315-322. Zhao, J.D.and X. Zhang . 1992. The polypores of china. Bibliotheca Mycologica. J. Cramer, Berlin. 209210. 83