Bringing the Bronze Age to Life in the Classroom

advertisement

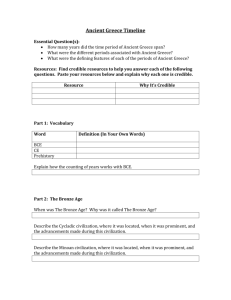

Premier’s Westfield History Scholarship Bringing the Bronze Age to Life in the Classroom Vicky Zinopoulos MLC School, Burwood Sponsored by Introduction One of the greatest challenges in teaching the Stage 6 Ancient History Syllabus is to create a learning environment that allows students to explore the richness of the ancient world rather than simply read about the descriptions in a textbook. Of course the only way to immerse oneself in the past is to visit the sites themselves, but as a student in Year 12 that is somewhat impossible. Similarly as a teacher of Ancient History it is essential to have hands on experience with the original source, but yet again one cannot always travel to the sites that we teach about. Despite new developments in pedagogy, it seems that when we teach Stage 6 Ancient History we tend to fall back to basic; content based, teacher centred activities. This is partly because of time constraints, but also because we feel compelled to teach to format due to pressures of the HSC year. For safety, we tend to focus on textbooks as our main teaching resource. While there is a wealth of information on the Internet, finding what is most appropriate and specific for our topic can be tedious at best. Also accessibility to such technology is not always available. Consequently, gone is the joy of experiential learning and welcome to chalk and talk and questions-answer activities, which of course does little to bring Ancient History to life. The challenge is how to make the past real for students in Stage 6 Ancient History? How can we generate energy and reality in our teaching practice? How can we bring the past to life in the classroom, so that students aren’t just paraphrasing textbook information but rather experiencing the actual archaeology and understanding the changes, the influences and the people of the past by drawing in-depth conclusions from the actual physical sources? My scholarship centred on visiting the sites, collecting and creating a variety of visual resources for teaching Bronze Age Greek Societies. These resources will include virtual tours, visual galleries and related student centred activities. These resources are designed to compliment and supplement current textbooks and online sites on Mycenaean Society and also to be flexible for students and teachers to use as part of their school’s program and to cater for different learning styles. Above all, my aim is to create interest and a love of life long learning by allowing students to explore and learn using technology. The Focus of the Study The primary focus of the study was to collect visual resources on Bronze Age sites in Greece and Turkey that could then be used to develop teaching resources for the Stage 6 Ancient History Syllabus – Bronze Age Greek Societies, with an emphasis on Mycenaean Society. My study tour also allowed me to survey a variety of additional sites and collect resources that could be used to develop and supplement additional units of work, such as case studies for the Preliminary Ancient History course. In collecting resources I concentrated on assessing what was available and accessible for teaching the syllabus outcomes and also concentrated on collecting material that would provide both depth and breadth in the scope of developing materials in the future as well as enriching the current text resources. The areas I visited included Athens, the Mycenaean sites of Mycenae, Tiryns, Argos, Lerna, Pylos, Orchomenos, Gla, and the burial sites of Volomidia. I also spent time in Crete, and collected resources from the sites of Knossos, Phaistos, Agia Triadha, Gournia, as well as the finds from the site of Akrotiri in Santorini. As part of the overall study I was also able to travel to the key areas of Olympia, Delphi, Vergina, the new Acropolis Museum, as well as Troy in Turkey. The MLC School Burwood has an established and progressive ICT program. Working in a laptop based school, the scholarship will allow me to use the information technology available and integrate ICT skills and CD-ROM based resources as teaching tools for differentiated activities that students can access via laptop. We currently incorporate ICT in our teaching of the Yr 12 syllabus through online units of work. These have proven to be very beneficial and highly engaging for the students. With the collection and collation of visual material, the scholarship will allow me to develop CD-ROM units of work that will focus on the archaeology of the site as the basis of students’ learning about the ancient societies. Through the development of teaching and learning resources that incorporate visual galleries and virtual tours concentrating on the key content areas of the syllabus, students will be able to analyse, apply and evaluate the material available in context of the evidence and draw conclusions about the societies from the sources themselves. This in turn, I hope will generate interest in and accessibility for teaching the Bronze Age option with a greater emphasis on student centred learning. I plan to make available to teachers in the near future the CD-ROM of the resources through the NSW History Teachers’ Association. The Archaeology of Bronze Age Greek Societies The key sites for teaching Mycenaean Society are Mycenae, Pylos and Tiryns. They are by far the best preserved of the ancient citadels which lend themselves to the creation of virtual tours to highlight the common architectural features of the palace structures, their sheer scale as well as allowing students an opportunity to embrace the archaeology in order to draw conclusions as to the societies development and relative prosperity. Mycenae, located on the Argolid plain is the best preserved of the sites for students to understand the concept and importance of an acropolis. It is also the biggest tourist drawcard of the Bronze Age sites making it a challenge to collect uninterrupted footage. Mycenae’s cyclopean walls and the grand walkway leading up to the centre of the citadel highlight the defensive features of the site. Clearly visible is the imposing and majestic Lion Gate with its monolith columns and lintel, post-holes from the wooden gate that would have barred the entrance still discernable as is the niche or guard house, whose function is still debated. On camera the grandeur of the structure against the rugged backdrop of the scenery and mountainous landscape clearly demonstrates to the student the importance of the sites geographical location and its importance within the Mycenaean world at the time. Beautifully maintained is also Grave Circle A within its walls, as is the original wall of the site, demonstrating change over time. Unfortunately the palace structure, the megaron and central hearth, the prodomos and courtyard were covered for conservation works and access through that area was barred. There was also significant work being undertaken on the houses and storage areas within the structure. Speaking with the archaeologists on site, they informed me that while the tourist industry was obviously beneficial for the continued interest and funding for maintenance, the constant movement through the fragile spaces off the path had taken its toll on the surrounding structures. At present their focus is preservation and they are in the process of securing the foundations of the House of Columns. I was also informed that they might consider restricting access to sections of the citadel in order to protect the limited and fragile foundations in certain areas of the site. In recent years they have constructed a cement path instead of visitors climbing ancient stairs as a means of limiting tourist traffic. The Northern Extension and Northern Gate also offered much opportunity to collect resources on the development of engineering skills and examples of economic growth in the society. Taking 360 degree footage, students can see the development of the citadel in the LHIIIB period and recognise key features as presented in their textbooks. Structures such as the Sally Port and underground cistern point to the defensive nature of the site and possible provisions for siege warfare, while the use of engineering techniques such as corbelling, allows students to draw comparisons between the sites and thus develop clear conclusions directly from the archaeological source. Walking through the site of Mycenae one understands that the citadel was without doubt a working community. The number of workshops within the site interconnected with narrow corridors supports the notion that the citadel was a commercial centre for the area. The relationship between these structures and the palace structure within the citadel is a difficult concept for students to understand without visual representation and aid of video footage. The virtual tour should allow students to gain a clearer understanding of the various structures within the citadel and also link these features with similar aspects from the other Mycenaean citadels. Consequently students can use the archaeology to draw conclusions about the function of citadels, palaces and workshops and make deductions concerning the everyday life of Mycenaeans, including social and administrative structures, their economy and the importance of trade. Equally impressive are the Tholos tombs at Mycenae; the Treasury of Atreus, the Tomb of Clytemnestra and Grave Circle B. These structures are excellent examples of Mycenaean burial practices. Together with footage from a variety of burial sites throughout mainland Greece and their corresponding artefacts, one can document and present to students through a visual gallery the development of burial practices in the Bronze Age from Pit graves, to Chamber tombs and moving to the elaborate Tholos tombs. Students can thus link the development to burial practices to the increasing economic prosperity and engineering development of the society. The site of Tiryns is the least best preserved of the three main Mycenaean sites but still offers an excellent opportunity to collect resources that will allow students to compare and contrast the function and purpose of citadels and draw conclusions about the nature of the society. Walking up to the citadel the cyclopean wall is an impressive site against the virtually flat terrain. In fact the site seems out of place when viewing it from the roadside. It is not until you reach the top of the citadel that you understand its prominent location, within a sea of fertile plains flanked by high mountains on either side, and the Bay of Nafplion, the key harbour for the area, only 4 km from the citadel. Tiryns was strategically located to take advantage of its natural resources and for its access to trade routes. Tiryns has similar defensive features to Mycenae. Its cyclopean walls date to the LHIIIB period and it too has an inconspicuous exit point. The palace is accessed via a steep and narrow ramped corridor leading towards the remains of an impressive gate “Monumental Gateway” of which only the monolithic supporting columns remain. There is again a large niche on the inside of the gateway. Moving into the structure you realise that in comparison to Mycenae, perhaps Tiryns had a different function. There are two features of the citadel that stand out in contrast to other sites. The palace has two discernable hearths and a bathroom. Using the visual resources student can analyse the function and purpose of these features to consider issues such as class structures, water technologies, the use of palaces and the function of Tiryns as a site in comparison to other citadels. The best preserved of the palaces was Pylos as it was excavated in the post war period. The Greek Cultural authorities have maintained the site’s foundations by covering it with an open-air roof, thus preserving this once most important Mycenaean site on the western coast of the Peloponnese. This has been possible as the palace is situated on a flatter acropolis with the absence of cyclopean walls. Pylos is an excellent example of Mycenaean palace architecture. Clearly laid out and labelled, students can clearly discern each room in the palace complex and from their features draw conclusions about Mycenaean political, religious and economic structures. With the aid of a virtual gallery, students enter the site through the prodomos, where they can see its column bases and corridors leading to the administrative areas of the palace. The key features of the site include the “Waiting Room” and “Pantry” (in which were found over 6000 kylixes), the extremely well preserved megaron with the central hearth where the coloured fresco around its base can still be seen and the bathroom with bathtub in tact. Furthermore towards the rear of the Fragment of a fresco from Pylos, (Chora Museum) palace are 3 wonderfully preserved oil magazines, which still have bases of the enormous pithoi burnt into the foundations of the stone benches on which they rested. Also of interest is the fact that Pylos has a second megaron with a much smaller but still well preserved hearth. These archaeological sources point to the fact that clearly Pylos was once an important political and economic centre. As the palace was destroyed by fire, fuelled by the vast quantity of oil stored in the complex, many of the clay artefacts within the palace were preserved and can now be found in the small museum in Chora. The Chora museum stores a fascinating display of artefacts from Pylos and also the surrounding burial grounds of Volimidia. Displays include examples of bronze and gold items from Pylos’ palace workshops, examples of Linear B tablets, a vast array of ritual and everyday pottery examples and exquisite wall frescoes that once adorned the megaron at Pylos. Along with the actual palaces and burial sites there was an opportunity to visit a large range of museums that house many of the Bronze Age Mycenaean finds. The key displays are to be found in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, the site museum at Mycenae and the Chora museum. These museums have well referenced exhibits that cover the range of thematic areas studied such as daily life, religion, administration, economy, death and burial. The wealth of artefacts found provide opportunity for students to discuss in detail the function and purpose of these items in context, and for them to link these ideas with an analysis of the primary sites in order to develop a comprehensive understanding of Mycenaean Society. My study tour also allowed me to understand the sheer scope and spread of Mycenaean Society throughout the Greek mainland. The Athens Agora Museum had a very interesting display of burial artefacts (kterismata) from Late Mycenaean graves in the area. The examples recorded demonstrate the development of burial techniques and importance of ritual in religious practice. This was further demonstrated by the large number of votive offerings found at the sites of Ancient Olympia and Delphi. It was surprising to see so many examples of everyday Mycenaean life at these sites as they are usually associated with Classical Greece. I was able to collect excellent examples of grave goods from these areas, including images of a Mycenaean pit grave in the middle of the ancient Olympic site, showing the spread of Mycenaean communities beyond the main centres. Other than the main cultural centres there are a number of additional sites that should be considered to provide students with an understanding of scope, sequence and change in Mycenaean society. Although poorly preserved, Orchomenos and Gla are excellent earlier examples of Mycenaean citadels and alternative palace structures. These sites also highlight the crucial impact of agriculture in the development of Bronze Age economy. There is also evidence of Mycenaean influence in north-western Greece at Dodonis, where the cult centre of Zeus was used as early as 2000BC. Furthermore graves dotted around both the Peloponnese and Attica, have unearthed many artefacts that are further evidence of religion, social customs, art styles and cultural practice. The site of Troy in Turkey and the related artefacts at Istanbul’s Archaeological Museum Throne Room at Knossos (reconstructed) also demonstrate the influence that the Greek Bronze Age world had on its neighbours. The terracotta and bronze items found within the site of Troy point clearly to the trade links between the Mycenaeans and their Aegean neighbours. While the site of Akrotiri on the island of Santorini was unfortunately still closed to the public, there is still a well stocked display of finds from the Early Mycenaean site at both the National Archaeological Museum in Athens and the Museum of Prehistoric Thera in Santorini. The current display of finds in Thera, traces the development of both artistic and technological skill from the Early Helladic to Middle Helladic period. Again there are also excellent examples of trade and cross-cultural influences from mainland societies and also further from Crete and even Egypt. Crete’s main Minoan sites provide a clear developmental link between the Minoan and Mycenaean worlds, and the Bronze Age societies of the Aegean and Mediterranean basin. The sites of Knossos and Phaistos provide excellent opportunity for students to develop a comprehensive understanding of palace societies. Both palaces are well preserved, Knossos being reconstructed, where students can tour the sites to gain detailed information on both the form and function of the palaces as the central sources of information on the nature of Minoan societies. In comparison, the site of Gournia, a defined trading town allows students to see a differentiation of sites dependant on the nature of trade and government structure. Unfortunately due to strike action in Crete during my visit many of the museums and sites were not accessible and thus limited the opportunity to collect resources. The archaeological museum in Heraklion was currently undergoing major renovations, but still displayed the key finds of the period in a smaller area. These included artefacts such as the Phaistos Disc, Agia Triadha Sarcophagus and beautifully decorated frescoes from Knossos. Conclusion Based on the research undertaken on the study tour it is clear that there is an enormous amount of archaeological resource available for teaching the Greek Bronze Age for the Studies of Society option in the Yr 12 course. The opportunity to visit the key sites and small regional museums has allowed me to collect materials that can be collated into resource pods for they key learning areas in the syllabus. The nature of these Bronze Age sites allows teachers to generate units of work around the archaeology rather than the content. By using the artefacts as a starting point for their learning, it enables students to reach their own conclusions and verify and support these with text material. Using the citadels as the primary and initial learning focus, students can tour of each of the key sites and use the archaeology to generate historical questions, acquire knowledge and understanding of the developments of these societies through a detailed exploration of the artefacts remaining from the period. The use of primary archaeological evidence will also provide students with the opportunity to develop more comprehensive understanding of the societies by incorporating description and analysis of the artefacts and source materials in their written discussions, thus producing more analytical and differentiated responses that demonstrate both depth and detail of the period. This is a unique opportunity to use ICT as a primary learning tool in the Stage 6 syllabus, to meld the ancient past with the modern future and to create opportunities for students to think creatively and analytically, to extract content and make links to wider historical issues as well as the contemporary world. By developing these units of work, I hope to provide access to a range of resources in a life like way, making the ancient world accessible to the students and hopefully bring the past to life in the classroom.