Here - University of St Andrews

advertisement

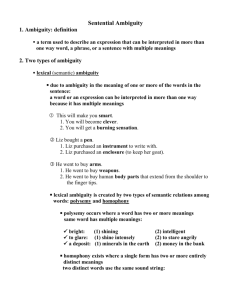

Ambiguity Here are ten English sentences, each to be discussed below. All are ambiguous. Which means that each has more than one interpretation, or reading. It would be a good exercise to try to spot all the different readings before you continue. Take your time. Remember that some are multiply ambiguous. And some are just hard to see. [1] Manson drove Sharon to the bank [2] The Thompson twins can fish [3] Ponting drives wide of mid-off [4] We must have the worst JCR food in Oxford [5] Bush is dangerous and mad or just plain stupid [6] Sally’s cousin is engaged to her former husband [7] Zebedee only reads books in libraries [8] Everyone in Balliol is dreaming about someone in Wadham [9] Florence wants to marry a Norwegian [10] Dougal is looking for a doughnut Examples [1] – [4] are of no especial logical interest, although they are freighted with philosophical significance. Taken together they constitute an extended argument against the KGB. They are intended as a proof, no less, that the phenomenon of ambiguity demonstrates two things. One, that messages determine sentences, and not the other way round. Two, that sentences do not have semantic properties like truth and falsity. Examples [5] – [10] are the ones which interest logicians. Because they are the ones where different structures of the various messages they encode produce different entailments, a different logic. And with the single exception of example [6], they are all to do with the important notion of scope. Learning to spot scope ambiguities is part of your training as a logician. Balliol versus Hodges – Examples [1] – [4] It is common for logicians - and Hodges is no exception - to treat the phenomenon of ambiguity as pathological. As an accidental, complicating feature of ordinary language, which gets in the way of clear analysis. And one which can be eliminated by appropriate means. They will do anything to avoid having to accept that the twin disciplines of Logic and Language must study messages and not sentences. The rhetorical structure of what follows is to allow Hodges and others like him all the manoeuvres they standardly deploy in order to eliminate ambiguity, and show that they still cannot do so. Example [1] Manson drove Sharon to the bank Did he drive his Chevy to the levee? Or just to the cashpoint? Did he drive Sharon in his car or with a pack of hounds? Indeed, was Sharon his wife or his car? Or even his favourite golf ball? And so on. This sentence is multiply ambiguous, but the ambiguities are purely lexical. All interpretations share the same phrase-marker1: S NP VP N V V Manson drove Adv N Sharon Prep to NP Det N the bank On every interpretation ‘drove’ is a Verb and ‘bank’ is a Noun. It’s just that there are multiple entries in the mental dictionary under ‘drove’ and under ‘bank’. (Try a printed dictionary like OED2: you will be surprised how many there are). Note the hallmarks of a pure lexical ambiguity: The various interpretations depend solely on changing the interpretation of single words, within a phrase class. The word ‘bank’ is also a verb in English, but there is no interpretation of [1] on which it so functions. In slogan form: Lexical Ambiguity: Same phrase-marker, different interpretations of individual words in the terminal string And that’s it, really, for lexical ambiguity. Lexical ambiguities are boring, by which I mean devoid of logical or philosophical interest. But even a simple example like [1] will serve to illustrate the First Noble Truth of Language. The existence of the phenomenon of ambiguity demonstrates that: Truth and falsity are not properties of sentences They are instead properties of the messages or thoughts which we encode in sentences. Suppose that Charles Manson took Sharon Tate, by car, to the local branch of Chase Manhattan to raid her bank account. Then there is a true interpretation of [1]. And suppose also that Manson did not pursue her to the 1 Phrase-markers are a favourite device from the theoretical study linguistics. And many talk of them as revealing the structure of sentences. But sentences only have sausage-structure, so that phrase-markers are really a crude attempt at the structure of messages. Which means, for those of you really on the ball, that they involve a sloppy conflation of the two levels that we are trying to keep distinct. For the symbols they use are labels for lexical items, and the groupings they indicate are groupings of message-components. Never mind. Just think of these diagrams as attempts at a picture of the message-structure. 2 Available online at : http://www.oed.com brink of the river with his hunting dogs. Then there is a false interpretation of [1]. So if truth and falsity belonged to sentences, [1] would be both true and false, a contradiction. Q.E.D. How might the Friends of Hodges respond? Is there some way of eliminating lexical ambiguity as a phenomenon? Well, yes. There is a standard manoeuvre, and one with which I have some sympathy. And it is the move which Hodges gestures at. Since the phenomenon is produced by having multiple entries in the mental dictionary for certain strings of letters (words), we could eliminate lexical ambiguity by saying that these are different words which unfortunately happen to be spelt the same way. And we could add subscripts – or some such device - to the strings of letters to differentiate the words. So we could instead have the following (now unambiguous) sentences Manson drove1 Sharon to the bank1 Manson drove2 Sharon to the bank1 Manson drove1 Sharon to the bank2 Manson drove1 Sharon to the bank3 Manson drove4 Sharon to the bank7 and so on. It wouldn’t be an easy language to use – you’d always be forgetting what the meanings were, and have to consult an actual dictionary – but it would be technically possible. O.K. Let’s give them that. Lexical ambiguity is at best a very superficial feature of languages, and could be eliminated. Example [2] The Thompson twins can fish Two distinct interpretations here. Perhaps the Thompsons work in, or run, a canning factory. Or maybe they are keen anglers. Clearly, both ‘can’ and ‘fish’ have different meanings on the two interpretations. So there is a temptation to call this a lexical ambiguity. But there is a crucial difference from [1]. This time the words in question hop around between phrase-classes, and the sentence therefore has two different phrase-markers: S NP The Thompson twins S VP NP Mod Vb can fish The Thompson twins VP V N can fish On the left-hand version ‘can’ is an Auxiliary verb – more specifically a Modal Auxiliary – and ‘fish’ is the base form of a Verb. The phrase-marker displays a particular grammatical pattern which generates sentences like these:The Houses of Parliament might explode The polluter should pay You may begin Bin Laden could win. On the right-hand version, ‘can’ is a straightforward transitive Verb, and ‘fish’ is a noun. This time we are looking at a different pattern, which generates sentences like these:Blair likes ambiguity Cherie trains rats New York frightens visitors And so on. These are quite different grammatical patterns, or structures, and so this is an example of structural ambiguity, aided and abetted by the lexical differences. In slogan form: Structural ambiguity: Different phrase-marker, with or without lexical variation. Those amongst you who are alert will have realized that this ambiguity could be eliminated in much the same way as Example [1]. Here the line that we have different words which just happen to be spelt the same is especially plausible. The two ‘can’s have different etymologies, different histories, one from Old English ,one from mediaeval Dutch. And not so very long ago they were spelt differently. And likewise with ‘fish’. It is an accident that the noun and verb are spelt the same. And again, it was not always thus. So we could have had The Thompson twins kann fish - they put fish into cans versus The Thompson twins canne fishe - they are able to angle O.K. Let’s give the FoH that one as well. Structural ambiguities which depend upon lexical variation are likewise a superficial feature of langauge, and could be eliminated. Of course, that would still leave structural ambiguities with no lexical variation in place. These are the pure scope ambiguities, of which [5] and [7] – [10] are examples. Let’s have a look at [5]. Example [5] Bush is dangerous and mad or stupid Both readings have the same phrase-marker as far as outermost structure goes: S N VP V Bush is Adj dangerous and mad or stupid All turns on the structure of the (complex) property ascribed to Bush. Is it overall a conjunction (left-hand diagram)? Or a disjunction (right-hand diagram)? Reading I and has major scope, or has minor scope3 Reading II or has major scope, and has minor scope [delete this instruction before you print off, and fill in the diagrams yourself. I have left you enough space] You can get a good working definition of scope from this diagrams. The scope of an item is the smallest chunk of the phrase-marker which contains it and something else. But think of it as defined correlatively. On the left, and has major scope relative to or. And on the right, and has minor scope relative to or. Some books will use the terminology wide scope versus narrow scope. The meaning is the same. And now we have a sense of Pure scope ambiguity: No lexical variation, no variation in phrase classes. Same phrase-marker, except for a swap in the scopes of certain items. Can pure scope ambiguities be eliminated? Again the answer is yes. Suppose we add explicit scopeindicators to sentences (brackets are an obvious choice). Then we could offer two different sentences for (e.g.) [5], producing Bush is dangerous and [mad or just plain stupid] versus Bush is [dangerous and mad] or just plain stupid In fact, in written English we often use commas for this very purpose, and in spoken English we can often pull the trick off with stress, intonation, pauses. O.K. Let’s give the KGB that one as well. Pure scope ambiguities could be eliminated by adding to sentences some way of indicating scope. But now for examples against which they are powerless. Example [3] Ponting drives wide of mid-off This one is easily missed. Imagine first the breathless commentator: “Flintoff is up to the crease, he bowls. And Ponting drives wide of mid-off, and it’s gone away to the Mound for four runs”. Here the message concerns a single event, cotemporaneous with the commentator’s report. And now think of Vaughan plotting with his men: “Remember, lads, Ponting drives wide of mid-off, so when he comes in we need to You needn’t bother to think about this just yet, but I am using bold type here for a special reason. It isn’t the word ‘and’ which has scope, but the concept and, the component of the message which is the interpretation of the word ‘and’, whatever that turns out to be. Bold type is a shorthand for just that: 3 and = the interpretation of the word ‘and’ move Jonesy a bit squarer.” Here the message concerns no single event, but instead Ponting’s current propensity, or tendency to bat in a certain way. But on either interpretation, the words are assigned the same meanings – so there is no lexical ambiguity – and the phrase-marker would be just the same – so there is no structural ambiguity. This particular kind of ambiguity – single event interpretation, versus propensity interpretation is everywhere in English It is clearly a systematic feature of the Grammar. Here’s another one. Example [3a] The Countess will walk You probably won’t see an ambiguity here without help. It’s hard to spot. After all, there’s no lexical ambiguity, since each word has only one possible meaning. And there’s no structural ambiguity, it would seem, for there is only one possible phrase-marker: S NP N The Countess VP Mod will V walk And yet [3a] is ambiguous. One interpretation predicts a single, future event, the Countess’s walking, as in (If she misses the bus tonight) The Countess will walk (home) The other describes a present propensity, the Countess’s propensity, or tendency to walk. If you like, her habit4 of walking home. As in (When she misses the bus) The Countess will (often) walk (home) This is obviously not an isolated phenomenon. Vast swathes of sentences exhibit this ambiguity between single event interpretations and habitual tendency interpretations. Compare (More often than not) Grannie leapt in through the window (Occasionally) Her Majesty enjoyed a spliff (From time to time) Tony faltered (In those days) Peter wore a cardigan which all express habitual messages, with their counterparts (Last Tuesday) Grannie leapt in through the window (At this year’s Trooping of the Colour) Her Majesty enjoyed a spliff (A moment later) Tony faltered (It was a special occasion, so) Peter wore a cardigan which describe single, past events. If you drop the clues in brackets, each of these is straightforwardly ambiguous. 4 . Indeed, let us choose a word to label these cases. interpretations, and habitual interpretations Let us distinguish between single-event Notice that this phenomenon shows there is more to ambiguity than lexical and structural differences. Ambiguity clearly cuts deeper than phrase-marker grammar plus dictionary. And therefore cannot be eliminated – indeed cannot be explained - by anything which stays at the level of words. Goodbye, KGB. Example [4] We must have the worst JCR food in Oxford And here is the same thing happening again. Andrew’s e-mail was meant to convey that he was appalled at the discovery. Carl took it as an aspiration for the future, and hence an implicit command. We are still suffering the consequences. And once again, all the words have the same meanings on either interpretation. No lexical ambiguity. And no difference in structure, either. So whatever is going on here, it cannot be dealt with at the level of words. Goodbye KGB. And notice again that this ambiguity is systematic. Here it is again: That dart might have landed in Baby’s eye Scope Ambiguities and Logic – Examples [5] – [10] We have already dealt with [5]. You can display the ambiguity by using brackets, or if you want to be flash you could use phrase-markers, as in Hodges. But let me use it as a vehicle to explain about scope and order. Scope differences correspond to the order of choices made in the encoding process, the order of construction of the message. [I suggest you write this part out for yourself. Again I have left space.] Example [6] Sally’s cousin is engaged to her former husband This is a straightforward ambiguity of cross-reference. Is Sally’s cousin going to marry Sally’s ex, or is she remarrying her own? All turns on whether the intended role of the pronoun ‘her’ is to pick up the reference of ‘Sally’ or of ‘Sally’s cousin’. And that is something a phrase-marker would not show, so we need a different kind of technical device to display it. I like Quine’s bracket-and-brace notation, as explained in the lecture. [I cannot reproduce the braces on the page – Word does not afford that facility. So it is up to you to make the rest of this page work, by filling in the braces yourselves] .Here is the idea. Take a sentence like John loves Susan but she hates him Here there is no ambiguity. The gender of the pronouns, and the background knowledge that ‘John’ is a man’s name, whilst ‘Susan’ is a woman’s name tells us that the pronoun ‘she’ refers back to Susan and the pronoun ‘him’ back to John. Which we could make explicit as follows: (John) loves (Susan) but (she) hates (him) Indeed, we now no longer need the pronouns: (John) loves (Susan) but ( ) hates ( ) So think of these pronouns as doing exactly the same job as the braces: devices of co-reference, as we call it. They are there to indicate which slots in the sentence are are chained to which. English has a whole set of devices for thus keeping track of who is who (or what is what). The pronouns, phrases like ‘the former’ and ‘the latter’, ‘the aforementioned’. Legalese has a potential infinity of them – ‘the party of the first part’, ‘the party of the second part’,… We even harness whole phrases to the task:John was in a hurry, and the young fool didn’t stop to think Mr. Gore was attacked again by Republican senators, but the presidential hopeful remained unflustered Gordon came round yesterday, and the bastard’s stolen my pension All these devices exist to perform the same function: to mark chains of co-reference. Which is precisely what the bracket-and-brace notation does. I almost forgot Sally’s marital entanglements. The two interpretations, as I’m sure you saw, can be displayed as (Sally)’s cousin is engaged to (her) former husband versus Example [7] (Sally’s cousin) is engaged to (her) former husband Zebedee only reads books in libraries Here we have a special case, worthy of note for two reasons. First, only is fantastically promiscuous – it can be attached to almost any chunk of the message, and yet end up in the same position in the output sentence. Second, there is only one item whose scope is in question, namely the scope of only. Normally, as we have seen and will see, scope ambiguities involve the interplay of the relative scopes of two items. Not so with only.5 Perhaps the easiest way in normal language to disambiguate is to re-encode the message using the phrase ‘The only’. For sentences thus constructed are unambiguous. And, which is nice, they make the scope of only explicit. Thus: The only person who reads books in libraries is Zebedee The only things that Zebedee reads in libraries are books The only thing that Zebedee does in libraries is read books The only thing that Zebedee does is read books in libraries [And so on. I suggest you fill in the others yourself] Example [8] Everyone in Balliol is dreaming about somebody in Wadham An important case. Examples of this phenomenon are always cropping up. Vital to see it as pure scope, and not as a lexical matter, down to differential meanings of some of the words. We call it a quantifier ambiguity, because all turns on the relative scopes of the two quantifiers encoded by the phrases ‘everyone in Balliol’ and ‘somebody in Wadham’. As with all scope ambiguities, this is a matter of order of construction of the message. Suppose you have in mind somebody in Wadham as the topic of your message. And what you want to say about her is that (amazingly – is she Zuleika Dobson?) is that everyone in Balliol is dreaming about her. Then somebody in Wadham is selected first, so that it has major scope, and everyone in Balliol is selected later, and plays a subordinate role, with therefore minor scope. And now suppose you have in mind a thought about the members of Balliol, as notional subject of your message, to the effect that they all share a common property, having each fallen in love with somebody (or other) in Wadham. Then everyone in Balliol is selected at an earlier stage of the encoding process, and so has major scope, whereas somebody in Wadham is selected at a later stage, and has minor scope. We could regiment these two readings with the (unambiguous) sentences There is somebody in Wadham such that: everyone in Balliol is dreaming about her 5 Much later, when you have learnt PredicateLogic, we will show you how, for logicians, it is the same notion of scope as everywhere else. But for now, be aware of the apparent difference. Everyone in Balliol is such that: there is someone in Wadham they are dreaming about. which make the relative scopes explicit. And, indeed, make it clear that this is just a matter of scope, the only difference being the order of the quantifiers. Notice, while you are here, that one interpretation entails the other. [Which way round is it?] Example [9] Florence wants to marry a Norwegian This one is important. Both in logic and in philosophy. If you understand it properly, for instance, you will see that the classic Argument from Illusion, which has bedevilled the Academy since before Plato, is just a sleight of hand, a piece of pure fraud. Maybe we will have time to discuss it in classes, and maybe not. But here it is. Imagine yourself confronting a stick in a glass of water. Which therefore looks bent. The purveyor of the Argument from Illusion wants you to reason as follows: “I am aware of something bent. But the stick is not bent. Therefore what I am aware of is not the stick. (And so must be something else, namely a private mental item which really is bent). Back to Florence and her Norwegian. The usual way of describing the ambiguity, for the untrained mind, is to see it as a matter of particular versus general. Either Florence wants to marry a particular Norwegian, or she wants to marry a general (i.e. any old) Norwegian. Please resist this temptation. For at least three reasons. I This makes it sound as though the ambiguity is somehow lexical, to be sheeted home to the interpretation of the word ‘a’. But it isn’t. It is a scope ambiguity. Indeed, a special type of scope ambiguity, for which we have reserved a special name. We call it a Notional – Relational ambiguity. II Every Norwegian is a particular Norwegian. What other sort is there? There certainly are no general Norwegians. And so III The sentence Florence wants to marry a particular Norwegian is still ambiguous. Does she want to marry a particular particular Norwegian, or does she want to marry any old particular Norwegian? Here is how to see it as scope. The regimentations are crude, and barely recognisable as English, but they should help you see the logic of it. Relational Reading: There is a Norwegian such that: Florence wants that: she marries him Notional Reading: Florence wants that: there is a Norwegian such that: she marries him. On the relational reading, we postulate the existence of an actual Norwegian, to whom Florence’s state of mind relates. It is he upon whom her mental state is focussed, he whom she wants to marry. And it may not matter to her whether he is Norwegian or not. She may not even know that he is Norwegian. The Norwegianness (what’s the right word? Norwegiosity?) is not put inside the scope of her mental state. On the notional reading, the Norwegianosity is part of the mental state (‘notion’ is an old technical term in philosophy for the content of a mental state. Hence the terminology). What she wants is merely to end up married to an instance of Norwegianosity (those intense blue eyes, those golden locks, that scent of Viking machismo). And here it doesn’t matter whether there be Norwegians or no. You could want to be married to a Neanderthal or a dodo, for that matter. [Here you may wish to expand a little for your own purposes, with diagrams or whatever. I leave you space.] Example [10] Dougal is looking for a doughnut Just like [9], this is a Notional-Relational scope ambiguity. And here are some others, some obvious enough, some quite cunningly disguised, for you to puzzle over. Mungo hopes to find a Yeti Little Miss Muffet was frightened at a spider This is a painting of a nobleman Nostalgia is a pining for a time that never was Jack wants to acquire a sloop Willard van Ormand Quine, legendary American logician and philosopher, once described the notional reading of this last as ‘merely wanting relief from slooplessness’. He clearly couldn’t resist the joke, since for once his logic slips a cog. Can you see why he is wrong? Watson wants to become a great detective. Fauxpas thinks that the greatest logician of the century was a fool --oOo-