Mining Confident Minimal Rules with Fixed

advertisement

Mining Confident Minimal Rules with Fixed-Consequents

Imad Rahal, Dongmei Ren, Weihua Wu, and William Perrizo

Department of Computer Science and Operations Research

North Dakota State University

imad.rahal@ndsu.nodak.edu

Abstract

Association rule mining (ARM) finds all the

association rules in data that match some measures of

interest such as support and confidence In certain

situations where high support is not necessarily of

interest, fixed-consequent association-rule mining for

confident rules might be favored over traditional ARM.

The need for fixed consequent ARM is becoming more

evident in a number of applications such as market

basket research (MBR) or precision agriculture.

Highly confident rules are desired in all situations;

however, support thresholds fluctuate with the

applications and the data sets under study as we shall

show later. In this paper1, we propose an approach for

mining minimal confident rules in the context of fixedconsequent ARM that relieves the user from the burden

of specifying a minimum support threshold. We show

that the framework suggested herein is efficient and

can be easily expanded by adding new pruning

conditions pertaining to specific situations.

1. Introduction

Association rule mining [1] is considered one of the

most important applications, by far, to ever emanate

from the data mining community. It was initially

proposed by Agrawal et al in 1993 [1] for market

basket data in what is known as Market Basket

Research (MBR). MBR data is usually in the form of

transactions each containing a list of items bought by a

customer during a single visit to a store. An association

rule of the form XY relates two sets of items, X and

Y, where X is called the antecedent and Y the

consequent of the rule. The underpinning relation

follows the direction of the arrow (from X to Y) and is

then described as “customers who buy X are very likely

1

This work was partially supported by the GSA grant ACT#:

K96130308

to buy Y”. The degree of likeliness of an association

rule is determined by external measures associated

with it. Two ubiquitously used measures are support

and confidence [1] [2]. The former measures the

number of transactions containing both the antecedent

and consequent sets of items (i.e. statistical

significance of the rule); meanwhile, the latter is used

to measure the proportion of the transactions

containing the antecedent that also contain the

consequent (i.e. strength of the rule). The originally

proposed goal in [1] for association rule mining is to

find all the rules with support and confidence

surpassing some minimum user-specified thresholds.

A number of approaches such as [6] and [14] use

extra parameters to code user’s rule preferences, thus,

reducing the total number of produced rules. Some of

the suggested parameters in the literature include lift

[6], conviction [6] [19] and reliability [3]. It is worth

noting that the naming used for the parameters is not

standard. A point made against those measures is that

while they attempt to capture user preferences more

fully, they obviously overburden the user with more

parameter tuning. Other algorithms take a different

approach for coding user preferences by requiring the

rules to have special formats through the integration of

item constraints [5]. One popular type of item

constraints is the consequent constraint where all the

rules are required to have the consequent specified by

the user. Numerous applications exist for consequentconstraint-based ARM (aka fixed-consequent ARM)

such as in MBR where one is interested in finding

which items are sold with a specific set of items of

interest for the purpose of running promotions on it.

Though this information can also be obtained through

the use of the general ARM scheme proposed by

Agrawal et al and then the application of a “postARM” processing step to retain only those rules that

have the specified item set as consequents, we believe

that since users are not interested in the rest of the rules

it would not be optimal to burden them with more

processing time for generating additional rules that will

eventually be removed through the “post-ARM”

processing step.

In this paper, we motivate the need for fixedconsequent ARM and present an algorithm based on

set enumeration trees [17] and P-trees [10] [16] for this

purpose bearing in mind the importance of alleviating

the burden of user parameter tuning. Our algorithm

produces confident minimal rules in an efficient

manner as we shall experimentally demonstrate.

This paper is organized as follows: In section 2 we

explain the notion of fixed-consequent, confidencebased ARM and motivate its need. Section 3 discusses

the set enumeration tree structure which is the

underpinning framework for our algorithm. In section

4 we present our proposed algorithm. Section 5

discusses details about the implementation devised for

this work in addition to some performance analysis.

We finally end this paper with some concluding

remarks in section 6.

2. Towards mining confident, minimal,

fixed-consequent rules

As aforementioned, the algorithm proposed herein

is based on the fixed-consequent constraint. Users

specify the set of items they wish to have as a

consequent for all the produced rules and then the

algorithm returns the rules that match. Some

applications that motivate this type of environment

include MBR and agricultural data analysis.

2.1. Fixed-consequent ARM

As mentioned in our introduction, using MBR,

some stores may want to find all the rules that have a

certain item or set of items as a consequent for the

purpose of running some promotions on those specific

items. In this context, a rule of the form XY, where

X and Y are item sets and Y is user specified, can

inform the analyst that since people that buy X are

inclined to buy Y then to promote the sales of Y we

can run some promotion on Y that also includes X.

Perhaps the use of fixed-consequent ARM is more

evidently needed in the context of precision

agriculture. Agricultural data is usually described by

visible reflectance bands (Blue, Green and Red),

infrared reflectance bands (e.g., NIR, MIR1, MIR2 and

TIR) and possibly some other bands of data gathered

from ground sensors such as yield quantity, yield

quality, and soil attributes like moisture and nitrate

levels. For simplicity and without loss of generality,

we will consider the following relation, R, as a

prototypic relation for this type of data: R (Red, Green,

Blue, NIR, …, Yield quality). In this context, analysts

are usually interested in finding high yield quality

given other properties like Red, Green, Blue, etc…; as

a result, using high yield quality as our fixed

consequent, we get rules describing the best reflectance

bands combinations that produce high yield [11]. Some

applications in medical research investigate patient

records to analyze the characteristics that lead to the

death of patients (or the existence of chronic diseases);

such a task can be accomplished in a similar manner.

2.2. Confidence-based ARM

We take confidence-based ARM to mean that users

only specify the confidence threshold of interest. In

general, users are always interested in high-confidence

rules. The higher the confidence of a rule, the lower the

error rate of generalizing it over the data set. A rule

with a confidence value of 95% tells us that we are

tolerating an error rate of 5% when we assume the

validity of the corresponding rule. We believe it should

be totally up to the user to specify the error rate that

can be tolerated.

In spite of the fact that we are always interested in

rules with high confidence values, we argue that

support fluctuates depending on the data set we operate

on. In some data sets, high support values are always

desired. This is the case with MBR data because store

managers always like to see high support values for

their rules. However, this is not the case with other

data sets. Considering our medical research example

again, let us suppose that we have a large database of

patient records. We are interested in finding what

combinations of attributes stored in those records that

imply the death of the patient. Ideally, we would

require our ARM application to detect such rules early

on so that we could attempt to diagnose the problem –

if any – before the support of those rules increases in

the database. Similar considerations apply to fraud and

copy detection.

In [9], Cohen et al motivates the need for lowsupport, high-confidence rules by observing that

usually high support rules are obvious and well-known

unlike low-support ones which provide “interesting”

insights into the data. Example applications for lowsupport high-confidence ARM mentioned in [9]

include copy detection [18] (for identifying similar

documents) and collaborative filtering (for making

recommendations to users based on behavior similarity

to others) [20].

We have devised our algorithm to generate the

highest support rules that match the user’s specified

minimum threshold without having the user to specify

any support threshold. By doing so, we would reduce

the number of parameters supplied on behalf of the

user relieving her from the burden of determining an

optimal value for the support threshold in order to

produce meaningful and interesting rules.

2.3. Rule minimality property

We will assume that the minimum confidence

threshold c (usually high) provided by the user

represents the threshold of interest; as a result, any two

rules having confidence values exceeding c, where the

antecedent of one of them is a superset of the

antecedent of the other, are to a great extent equally

interesting to the user. Support comes into the picture

to tip the scales in the direction of the rule with higher

support. For example, suppose we generate two rules,

R1 and R2, with confidence values greater than the

confidence threshold where R1 is “formula milk”

“diapers” and R2 is “formula milk”, “baby shampoo”

“diapers”. R1 and R2 are considered very equally

interesting to the user, and thus we select only the one

with greater support value and prune the other. Since

R2’s antecedent is a superset of R1’s, then R1’s support

is surely greater than or equal to R2’s. A more

contextual justification for our choice would be by

arguing that since the user knows that “formula milk”

“diapers” from R1 no new knowledge is given by

R2:“formula milk”, “baby shampoo” “diapers”.

In this context, we refer to R1 as a minimal rule and

R2 as non-minimal. Formally speaking, a rule, R, is

said to be non-minimal, if there exists at least one other

rule, S, such that both rules have confidence values

greater than the minimum confidence threshold, have

the same consequent, and the antecedent of R is a

superset of that of S. Producing minimal rules can be

viewed as an extension over previous approaches in the

literature such as [9] and [12] which restrict their work

to rules of item pairs only (i.e. one item in the

antecedent and one item is the consequent).

The work in [4] [7] [15] support our claim of the

importance of minimal rules. [4] uses the notion of

non-redundant or minimal rules to refer to rules with

the smallest possible antecedents and largest possible

consequents. This matches our rule minimality

definition to a large extent since we also require the

antecedent to be as small as possible; however, we

relax the requirement on the consequent because we

are dealing with fixed consequents. [7] emphasizes the

importance of “small” rules in the context of genome

analysis while [15] extends it to medical data.

3. Set enumeration trees

The algorithm presented herein is modeled after a

well-known set enumeration structure that supports

complete and non-redundant search of an item space,

the Set Enumeration (SE) tree [17]. The SE tree

framework provides us with a scheme for enumerating

all possible subsets of an item set without redundancy

by imposing an ordering on the set of items, and for

presenting them graphically in a tree structure thus

shifting our problem from a random subset search

problem to an organized tree search problem. The

reader is referred to [17] for more details on SE trees.

In the general context of ARM, a number of

publications in the literature have suggested using SE

trees for mining association rules. [8] proposes two

new tree data structures based on SE trees along with

algorithms that demonstrate significant speed and

storage savings. [5] presents an interesting approach

for mining association rules with fixed consequents at

very low support thresholds. As we shall demonstrate

later in this paper, the structure of the SE tree can be

utilized for our problem too as it provides a framework

which facilitates easy augmentation of pruning

conditions along its branches thus reducing the space

of considered item subsets and focusing only on what

adheres to our notion of “interestingness”.

4. The proposed approach

We say that transaction, t, supports an item set, I, if

every item in I exists in t. As in [1] and [2], the support

of an item set is defined by the proportion of

transactions supporting that item set. The support of a

rule is the support of the union of all item sets existing

on both sides of the rule. The confidence of a rule is

defined as the proportion of transactions supporting the

antecedent of the rule that also supports the consequent

of the rule and is calculated as the ratio between the

support of the rule and the support of the antecedent of

the rule.

4.1 Pruning

After the user specifies a minimum confidence

threshold, minconf, and a consequent item set, C, our

algorithm proceeds by the creating an SE-tree

structure. Every node in the tree represents the

antecedent item set of the rule IC. Whenever we

create a new node, n, in the tree and label it with an

item set, I, we apply the pruning conditions listed next

to check whether we can terminate the processing at n

pre-maturely thus reducing the space. By terminating a

node, we stop further processing at that node and no

longer list any item sets under it. We exploit the

following three pruning conditions:

Zero-confidence pruning: If the confidence

(IC) = 0, then terminate n.

One-support pruning: If the support (IC) = 1,

then terminate n.

Minimality pruning: If the confidence (IC) >=

minconf, then terminate n

Zero-confidence pruning is a simple and straight

forward pruning condition based on the observation

that if the support of a certain item set, I, is zero then

every superset of I has a zero support; as a result, any

rule formed by replacing the antecedent of a rule

having a zero confidence by a superset of that

antecedent will also have a zero confidence. To justify

that, suppose a rule IC has a support of zero (i.e.

support(I U C) = 0); as a result, the confidence of IC

is also zero – recall that confidence(IC) =

support(IC) / support(I). Suppose that I’ is a superset

of I; we know that support of (I’ U C) is zero since (I’

U C) is a superset of (I U C). As a result, support of

(I’C) is zero and thus confidence of I’C is also

zero. In short, if we know that a rule I C has a zero

confidence, then there is no need to process the

supersets, I’, of I and calculate the confidence values of

the rules I’C.

Rules with support equal to 1 are based on a single

sample from the database and thus are not rules per se.

Note that if the support of any rule IC is 1, then any

non-minimal rule formed from this rule can not have a

support greater than 1. In practice we can easily

combine the previous two pruning conditions by

pruning a node if its support is less than or equal to 1;

this is because the confidence of a rule is equal to zero

if and only if its support is equal to zero. Hereinafter,

we shall refer to those two pruning conditions

combined as the support-less-than-two pruning.

The minimality pruning condition is based on our

previous argument presented in section 2.3 for the need

to remove non-minimal rules. Once we generate a rule

R: IC with confidence value exceeding minconf, we

terminate the node, n, that generated R because all

successor nodes of n may only generate non-minimal

rules of R according to our definition of minimality.

As noted earlier, other pruning conditions that

pertain to special situations can be easily added to our

set of conditions and tested in a similar manner. Each

pruning condition when satisfied results in node

termination.

Our algorithm employs the two pruning conditions,

support-less-than-two pruning and minimality pruning,

to prune the SE tree. Every time we generate a new

item set, I, at some node, n, three scenarios may

transpire:

Support of (IC) is less than 2; we terminate n

Confidence of (IC) is in the range (0, minconf)

exclusively; we continue processing without

terminating n

Confidence of (IC) is greater or equal to

minconf; we terminate n and output IC as a rule

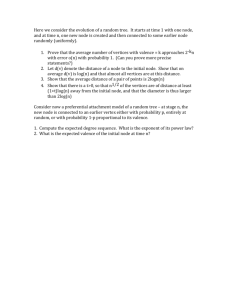

The formal algorithm is depicted in Figure 2. Note

that our algorithm is complete in terms of producing all

confident minimal rules. We omit the proof due to

space limitations.

Input: an ordered list of items, minconf, and the

consequent item set

Output: set of minimal rules satisfying minconf

Algorithm:

Create the root node (the empty set)

For every item, I, in our ordered list of items, do

the following:

o Generate a new node, n

o Insert n under the root from right to left

o Label n with I

o Depending on the resulting confidence and

support of (IC), proceed with one of the

following:

If support of (IC) is less than 2 then

terminate n

If confidence of (IC) is greater or equal

to minconf then terminate n and output

IC as a rule

If confidence of (IC) is in the range (0,

minconf) exclusively then for every unterminated node, Unter-n, to the right n

(working from highest level in the tree

down, and at each level processing nodes

right to left)

Generate a new node, nn

Insert nn under n from right to left,

Label nn with the label of Unter-n.

(Note that the item set represented by nn

is the union of the items in n and Untern)

Recursively repeat the confidence

testing process for nn

Figure 2. The formal algorithm.

4.2 Ensuring rule minimality

Suppose we have a set of items {1, 2, 3, …, 11} with

11 being the fixed consequent. Suppose further that we

are currently working with node 1 and that to the right

of 1 we have two un-terminated nodes, 9 and 8,9. Both

nodes will be considered with 1 because node 8,9 falls

under node 8 in the tree and is thus independent of the

result of the join of 1 and 9. A possible scenario would

be for both rules, 1,911 and 1,8,911, to succeed

thus we end up generating a non-minimal rule,

1,8,911 in this case.

Another scenario we need to consider is when rule

1,911 has support 0 or 1, then there is no need to try

rule 1,8,911 because its support is also going to be 0

or 1. In this scenario, our algorithm will not produce

undesired rules but will test for rules whose outcome is

known beforehand which undesirable because this

involves the time-consuming process of scanning a

large database to compute the support and confidence

of the rule – in cases where a non-vertical database

layout is adopted.

To rectify this problem, we associate a temporary

taboo list (TL) with every item, I, which will save all

the nodes that are pruned under I. For example, if

1,911 is not a confident rule or its support is less

than 2, then we append 9 to 1’s taboo list (TL1 for

short). In later steps, before we test for a new potential

rule under node 1, 1,X11, we check if any subset of

X is in TL1. If so, we directly terminate X under 1 and

add X to TL1. This may seem unfeasible at first;

however, an efficient implementation has been devised

as we shall discuss in more details in section 5.2.

parent node. In practice, we do not directly store the

number of 1s, but a 1 if the node contains only 1s and a

0 otherwise. Nodes containing only 1s or only 0s are

considered pure (otherwise they are mixed) and are not

partitioned further – called pure-1 and pure-0,

respectively. This aspect is referred to as P-tree

compression [10] [16] and is one of the most important

characteristics of the P-tree technology. Note that we

can easily differentiate between pure-0 nodes and

mixed nodes by the fact that pure-0 nodes have no

children (i.e. they are leaf nodes). Figure 4 shows the

P1-trees corresponding to the P-trees in Figure 3.

P1-trees are manipulated using operations such as

AND, OR, NOT and ROOTCOUNT (the count of the

number of “1”s in the bit group represented by the tree)

in order to query the underlying data. The reader is

referred to [10] [16] for more details on P-trees and

their logical operators.

Column1 Column2

0

1

0

1

0

1

0

1

1

0

0

0

1

1

1

1

5. Implementation & performance analysis

5.1. The P-tree technology2

Our implementation for this work is based on an

efficient data structure, the P-tree (Predicate or Peano

tree). P-trees are tree-like data structures that store

relational data in a loss-less compressed column-wise

format by splitting each attribute into bits, grouping

bits at each bit position, and representing each bit

group by a P-tree. To create P-trees from transactional

binary data, we store all bit values in each binary

attribute for all the transactions separately. In other

words, we group all bits, for all transactions t in the

table, in each binary attribute, separately. Each such

group of bits is called a bit group. Figure 3 shows the

process of creating P-trees from a binary relational

table. Part b) of the figure shows the creation of two bit

groups, one for each attribute in a). Parts c) and d)

show the resulting P-trees, P1 and P2, one for each of

the bit groups in b). P1 and P2 are constructed by

recursively partitioning the bit groups into halves.

Each P-tree will record the total number of 1s in the

corresponding bit group on the root level. The second

level in the tree gives the number of 1s in each of the

halves of the bit group. The first node from the left on

the second level will give the number of 1s in the first

half of the bit group; similarly, the second node will

give the number of 1s in the second half of the bit

group. This logic is continued throughout the tree with

each node recording the number of 1s in either the first

or the second half (depending on whether it is the left

or right node) of the bit group represented by the

2

Patents are pending for the P-tree technology.

a) A 2-column table

0

0

0

0

1

0

1

1

1

1

1

1

0

0

1

1

b) The resulting two

bit groups

6

3

0

3

1

4

2

2

0

2

1 0

d) P2

c) P1

Figure 3. Construction of basic P-trees.

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

1

0

0

1

1 0

a) P1

b) P2

Figure 4. Pure-1 Trees.

Note that by using P-trees, we can compute the

confidence of rules in a quick and efficient manner

(without any database scans). Each item i will be

represented by a P-tree, Pi; to get the support of an

item, we issue a ROOTCOUNT operation on the P-tree

of that item. To get the support of an item set of size

more than one, we AND the P-trees of the items in the

item set and then issue a ROOTCOUNT operation on

the result.

5.2. Taboo lists

For every new item I, we create a new node under

the root and test for potential rules with all possible unterminated nodes lying to I’s right. The actual node

creation order of the SE tree is the lexicographic subset

ordering of the items in the given item list. For

example, the node creation order for the set {1,2,3}

would be: {1}, {2}, {1,2} ,{3}, {1,3}, {2,3}, {1,2,3}.

This ensures that every item set has all its subsets

before it.

For every item, I, we maintain a TLI which saves

the item sets whose outcomes, when joined with I, are

known beforehand and thus need not be tested. In our

implementation, each TLI is a P-tree having a size

equal to the number of un-terminated nodes to the right

of I (i.e. all nodes that I will be tested with). A value 1

is used for nodes which, when joined with I, result in

the firing of some pruning condition; thus, none of

their supersets need to be tested with I. The remaining

TLI entries will be 0s. For example, for the set of items

{1,2,3,4}, suppose that the nodes created so far are:

{1}, {2}, {1,2} ,{3}, {1,3}, {2,3}, {1,2,3}. For node 4,

we initialize a TL4 having 7 entries all containing 0s

initially. If the joining of item 4 with node {2} results

in firing at least one pruning condition, then the second

entry pointing to item set {2} is flagged with 1, and so

are all entries containing 2 (i.e. entries pointing to

{1,2}, {2,3} and {1,2,3}). But how can we efficiently

tell which other entries contain item 2? We maintain

for each item an index list as a P-tree (called an index

P-tree) that has a 1 value for every position that this

item exists in. For example, item 1 will have the

following index list (it will be stored as a P-tree but we

are just listing the entries in a list for convenience):

1,0,1,0,1,0,1. In other words, viewing the nodes of the

SE tree in node creation order, item 1 occurs in node

positions 1, 3, 5 and 7. Every new node added to the

SE tree results in the expansion of all index P-trees by

either a 1, if the corresponding item is in the new node

added, or a 0, otherwise.

Going back to the previous scenario where the

joining of item 4 with node {2} results in firing at least

one pruning condition and thus node {2} need to be

added to TL4, we simply OR the index P-tree of item 2

with TL4. In general, if we want to add node {x,

y,…,z} to some taboo list, TLI, we AND the index Ptrees for all items in the node (i.e. AND index P-tree of

x with that of y … with that of z). The result will give

us where item set {x, y,…,z} occurs. We then OR the

resulting P-tree index with TLI which results in

appending node {x, y,…,z} to TLI.

We maintain the taboo lists and index lists as Ptrees as this will give us faster logical operations and

compression. In addition, in the case of taboo lists, it

could speed the node traversal especially in cases

where there many consecutive 1’s. For example,

suppose the entries in a taboo list are: 1111 0011.

Figure 5 below shows the corresponding P-tree of the

given taboo list.

0

1

0

0

1

Figure 5. The resulting taboo list in P-tree

format.

In this example, instead of going through the first

four nodes sequentially and then skipping them

because they are flagged, using a P-tree to represent

the taboo list, we can directly skip the first 4 entries

because they form a pure-1 node on 2nd level of the Ptree.

It is worth mentioning that our traversal through the

itemset space using taboo lists is very similar to a

popular approach used in AI literature and known as

Tabu search [13]. The idea in Tabu search is to traverse

the space in a more effective manner by avoiding

moves that result in revisiting points in the space

previously visited whose outcome is known not to be

acceptable (hence the name "tabu”). The fact that the

union of I and X produces an infrequent itemset implies

that future joins of I with any superset of X will

produce an infrequent itemset; a scenario similar in

essence to revisiting a point in the search space whose

outcome is known to be unsatisfactory and which

could be circumvented by putting the point on a Tabu

list. Because of the difference in context and problem

definition, we refer to our lists as taboo lists instead of

Tabu lists.

5.3. Comparison analysis

To the best of our knowledge, no previous work has

attempted to mine the type of rules we are considering.

We find [5] to be particularly interesting as it proposes

an algorithm called Dense-Miner which is capable of

mining association rules with fixed consequents at very

low support thresholds. For the lack of a better

benchmark, we will compare our approach with DenseMiner; however, we have to emphasize that a number

briefly describes the two datasets by listing the number

of transactions, items, and items per transaction for

each data set.

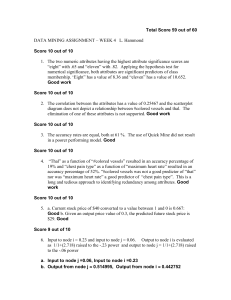

Connect-4 Dataset

250

Number of rules

200

150

100

50

99

99

.5

80

85

70

75

90

95

91

.5

90

91

74

80

85

Table 3.

49046

7117

70

75

PUMSB

60

65

43

50

55

129

40

45

67557

30

35

Connect-4

160000

140000

120000

100000

80000

60000

40000

20000

0

20

25

Items per

trans.

PUMSB-4 Dataset

Number of rules

Items

60

65

Confidence Threshold (%)

Table 2. Data sets description

Trans.

50

55

40

45

30

35

0

20

25

of fundamental differences exists between the two

approaches which we briefly outline next:

Dense-Miner mines all association rules while we

only mine minimal, confident rules

Dense-Miner uses support as a pruning mechanism

while this is not the case in our work (In reality we

also use support pruning, but in our case, the

support threshold is always set to 2 – as an

absolute threshold)

In terms of rule overlap between the two

approaches, all rules produced by our approach that

have a support value greater than the minimum support

threshold used for Dense-Miner will be produced by

Dense-Miner also.

Confidence Threshold (%)

P-tree based

Connect-4 Dataset

Figure 7. Number of rules produced.

Dense Miner

3500

3000

Time (s)

2500

2000

1500

1000

500

0

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90 100

Confidence Threshold (% )

P-tree based

PUMSB Dataset

Dense Miner

2500

Time (s)

2000

1500

1000

500

0

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Confidence Threshold (% )

Figure 6. Speed comparison.

All experiments were conducted on a P-II 400 with

128 SDRAM running Red hat Linux 9.1. C++ was

used for coding. We experimented on two real-life

dense data sets, Connect-4 and PUMSB, which are

available at the UCI data repository. Table 2 below

Figure 6 shows the time in seconds needed to mines

rules at different confidence thresholds by our

approach (P-tree based) and Dense-Miner. As

aforementioned, Dense-Miner mines all rules using

support pruning. It uses a variant of support referred to

as coverage and defines the minimum coverage

threshold as the minimum support divided by support

of the fixed consequent. Results for Dense-Miner are

observed with minimum coverage threshold fixed at

1% and 5%, respectively.

Our approach, on the other hand, mines only

minimal rules without using any support pruning. It is

very clear from the figure that users interested in

minimal rules without support would prefer our

approach as the time needed is many orders of

magnitude less than that of Dense-Miner.

The user might notice from both parts of Figure 6

how the two approaches differ in the way they produce

the rules. Dense-Miner takes more time at lower

confidence while our approach takes more time at

higher confidence thresholds. This is mainly because

our approach mines minimal rules using only

confidence pruning and the higher the confidence

threshold, the more difficult it would be to get

confident rules high in the SE tree; as a result, the SE

tree grows deeper and thus requires more time to

traverse. Dense-Miner, on the other hand, mines all

rules and it is very logical to have more rules satisfying

lower confidence thresholds (and vice versa) which

obviously requires more time to mine.

The number of rules produced by Dense-Miner

ranges from around 500,000 rules to less than 10 rules

over both data sets. Figure 7 shows the number of rules

produced by our approach over the two data sets at the

different confidence thresholds. The same discussion

presented in the previous paragraph applies here

regarding the larger (smaller) number of rules

produced at higher (lower) confidence thresholds.

6. Conclusion

In this paper we proposed a framework based on

SE-trees and the P-tree technology for extracting

minimal, confident rules using fixed-consequent ARM.

Our methodology relieves the user from the burden of

specifying a minimum support threshold by extracting

the highest support rules that satisfy user confidence

threshold. Albeit, to the best of our knowledge, no

previous work has attempted to mine minimal,

confident rules with fixed consequents, we provide a

comparison analysis study showing how well we

compare to other close approaches in the literature.

In terms of limitations, we acknowledge that our

approach suffers in situations where the desired rules

lie deep in the tree because a large number of nodes

and levels need to be traversed then. A future direction

in this area targets finding measures for estimating the

probability of rule availability along certain branches

and quitting early in cases where such probability is

low.

7. References

[1] R. Agrawal, T. Imielinski, and A. Swami, Mining

association rules between sets of items in large databases.

Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD (Washington, D.C.),

1993.

[2] R. Agrawal and R. Srikant, Fast algorithms for mining

association rules. Proceeding of the VLDB (Santiago, Chile),

1994.

[3] K. Ahmed, N. EI-Makky and Y. Taha, “A note on

‘Beyond Market Baskets: Generalizing association rules to

correlations’”. ACM SIGKDD Explorations, Vol. 1, Issue 2,

pp. 46-48, 2000.

[4] Y. Bastide, N. Pasquier, R. Taouil, G. Stumme, and L.

Lakhal, Mining Minimal Non-Redundant Association Rules

using Frequent Closed Item sets. Proceedings of the First

International Conference on Computational Logic (London,

UK), 2000.

[5] R. Bayardo, R. Agrawal, and D. Gunopulos, ConstraintBased Rule Mining in Large, Dense Databases. Proceedings

of the IEEE ICDE (Sydney, Australia), 188-197, 1999.

[6] R. Bayardo and R. Agrawal, Mining the most interesting

rules. Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD (San Diego, CA),

1999.

[7] C. Becquet, S. Blachon, B. Jeudy, JF. Boulicaut, and O.

Grandrillon, “Strong-association-rule mining for large-scale

gene expression data analysis: a case on human SAGE data”.

Genome Biology, 3(12), 2002.

[8] F. Coene, P. Leng, and S. Ahmed, “Data Structure for

Association Rule Mining: T-Tree and P-Trees.” IEEE

transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 16(6):774778, 2004.

[9] E. Cohen, M. Datar, S. Fujiwara, A. Gionis, P. Indyk, R.

Motwani, J. D. Ullman, and C. Yang, “Finding interesting

associations without support pruning”. IEEE Transactions on

Knowledge and Data Engineering, 13(1):64–78, 2001.

[10] Q. Ding, M. Khan, A. Roy, and W. Perrizo, The p-tree

algebra. Proceedings of the ACM SAC, Symposium on

Applied Computing (Madrid, Spain), 2002.

[11] Qin Ding, Qiang Ding, and W. Perrizo, Association

Rule Mining on Remotely Sensed Images Using P-trees.

Proceedings of the PAKDD, Pacific-Asia Conference on

Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Springer-Verlag,

Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence 2336, 66-79, May

2002.

[12] S. Fujiwara, J. D. Ullman and R. Motwani, Dynamic

Miss-Counting Algorithms: Finding Implications and

Similarity Rules with Confidence Pruning. Proceedings of the

IEEE ICDE (San Diego, CA), 2000.

[13] F. Glover, “Tabu Search for Nonlinear and Parametric

Optimization (with Links to Genetic Algorithms).” Discrete

Applied Mathematics 49 (1-3): 231-255, 1994.

[14] M. Klemettinen, H. Mannila, P. Ronkainen, H.

Toivonen, and A. Verkamo, Finding interesting rules from

large sets of discovered association rules. Proceedings of the

ACM CIKM, International Conference on Information and

Knowledge Management (Kansas City, Missouri), 401-407,

1999.

[15] C. Ordonez, C. Santana, and L. de Braal, Discovering

Interesting Association Rules in Medical Data. Proceedings

of the IEEE Advances in Digital Libraries Conference

(Baltimore, MD), 1999.

[16] W. Perrizo, Peano count tree technology lab notes.

Technical Report NDSU-CS-TR-01-1, 2001.

http://www.cs.ndsu.nodak. edu /~perrizo

/classes/785/pct.html. January 2003.

[17] Ron Raymon, An SE-tree based Characterization of the

Induction Problem. Proceedings of the ICML, International

Conference on Machine Learning (Washington, D.C.), 268275, 1993.

[18] N. Shivakumar, and H. Garcia-Molina, Building a

Scalable and Accurate Copy Detection Mechanism.

Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory

and Practice of Digital Libraries, 1996.

[19] P. Tan, and V. Kumar, Interestingness Measures for

Association Patterns: A Perspective, KDD’2000 Workshop

on Post-processing in Machine Learning and Data Mining,

Boston, 2000.

[20] H.R. Varian, and P. Resnick, Eds. CACM Special Issue

on Recommender Systems. Communications of the ACM 40

(1997).