1 Krakow 10 March 1987 Dear Sir Isaiah, Thank you very much for

advertisement

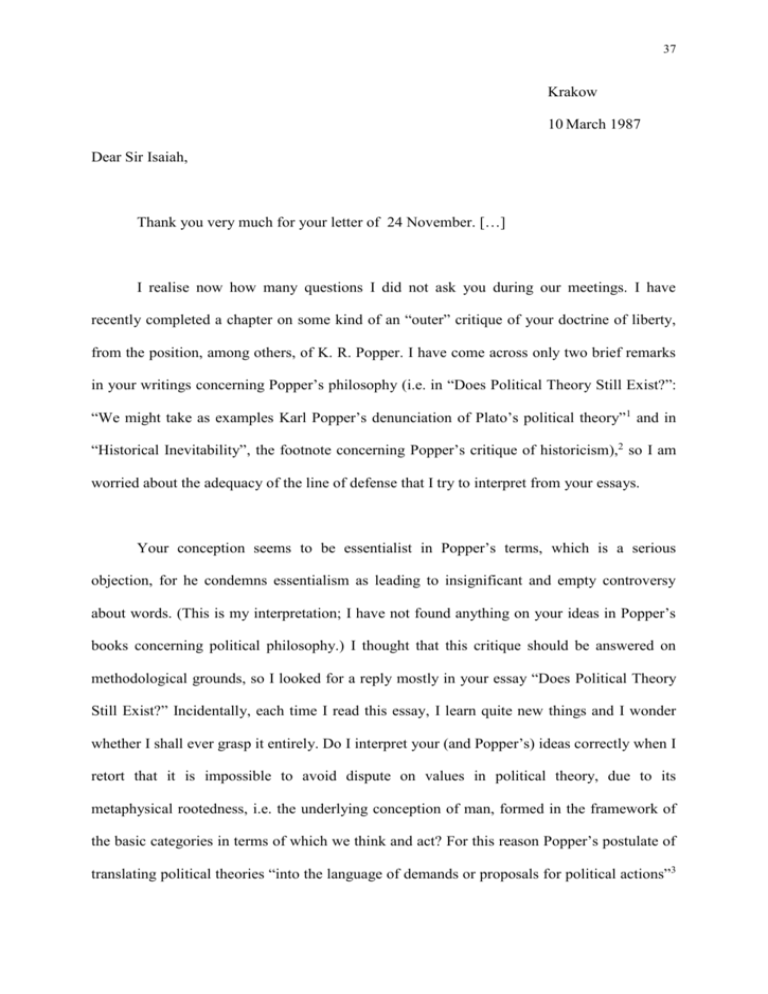

37 Krakow 10 March 1987 Dear Sir Isaiah, Thank you very much for your letter of 24 November. […] I realise now how many questions I did not ask you during our meetings. I have recently completed a chapter on some kind of an “outer” critique of your doctrine of liberty, from the position, among others, of K. R. Popper. I have come across only two brief remarks in your writings concerning Popper’s philosophy (i.e. in “Does Political Theory Still Exist?”: “We might take as examples Karl Popper’s denunciation of Plato’s political theory”1 and in “Historical Inevitability”, the footnote concerning Popper’s critique of historicism),2 so I am worried about the adequacy of the line of defense that I try to interpret from your essays. Your conception seems to be essentialist in Popper’s terms, which is a serious objection, for he condemns essentialism as leading to insignificant and empty controversy about words. (This is my interpretation; I have not found anything on your ideas in Popper’s books concerning political philosophy.) I thought that this critique should be answered on methodological grounds, so I looked for a reply mostly in your essay “Does Political Theory Still Exist?” Incidentally, each time I read this essay, I learn quite new things and I wonder whether I shall ever grasp it entirely. Do I interpret your (and Popper’s) ideas correctly when I retort that it is impossible to avoid dispute on values in political theory, due to its metaphysical rootedness, i.e. the underlying conception of man, formed in the framework of the basic categories in terms of which we think and act? For this reason Popper’s postulate of translating political theories “into the language of demands or proposals for political actions”3 38 cannot be realised. In your another essay, “Political Theory in the Twentieth Century” I have encountered an excerpt that seems to be directly addressed to Popper’s chief political maxim: “Minimize unhappiness”: “men do not live only by fighting evils. They live by positive goals, individual and collective, a vast variety of them, seldom predictable, at times incompatible.”4 Was this statement somehow related to Popper’s views or not? I would also like to ask you what you think about my own ideas on the topic, namely it seems to me that Popper is, in some way, inconsistent. In his intellectual autobiography he claims to be a pluralist: “we shall always to have to live in an imperfect society. That is so not only because even very good people are very imperfect, nor is it because, obviously, we often make mistakes because we do not know enough. Even more important than either of these two reasons is the fact that? there always exist irresolvable clashes of values: there are many moral problems which are insoluble because moral principles may conflict.”5 But, at the same time, he attempts to stop the discussion on values. Returning to your ideas, Popper’s technological approach would fit in with a vision of some monolithic society, which, for sure, he would not accept. Moreover, it seems to me that Popper happens to betray his own anti-essentialism. I have come across a passage in The Open Society and Its Enemies devoted to the critique of Plato’s interpretation of the concept of justice. Popper claims that Plato distorted the meaning of the concept, by having used it as a synonym for “that which is in the interest of the best State.”6 Popper asks a typical essentialist question: “What do we really mean when we speak of ‘Justice’?,” and provides an answer to it, though not without some reservation that it amounts to his interpretation of “the humanitarian general outlook.”7 In this way, quite unintentionally, he acknowledges the importance of conceptual analysis, at least to the extent to which distortions are involved. Thus, Popper’s methodological naturalism in the social sciences seems to me to be some sort of simplification for the sake of the unity of his philosophical system. 39 On the other hand, I have found some elements of methodological nominalism in your doctrine. Your definitions of the positive and negative liberty satisfy Popper’s methodological demands: “The first of these political senses of freedom or liberty […] I shall call ‘the negative sense’ […] The second I shall call ‘the positive sense’ […].”8 Moreover, your conception of freedom is not an insight into the meaning or nature of freedom, but a critical examination of the two main meanings that have been ascribed to it. Your thesis of the particular susceptibility to distortions of the positive doctrines of liberty seems to be testable, as far as the practical consequences of adopting each of the two concepts are concerned. Thus, your essay is less essentialist that it might seem. I have yet another, quite different problem. At the end of my stay in Oxford I met Dr. Pelczynski, who criticized your doctrine of negative liberty as devoid of any conception of the agent (either rational or emprical or any other). I must confess that I do not know whether this is a serious problem and how to answer this objection. […] Let me now once again thank you for the invaluable benefit that I gained from your writings and from our conversations. Thanks to you the work on my Ph.D. dissertation and all that has been connected with it has become one of the most important things in my life. Even if my greatest intellectual adventure were to finish now, it will never lose its great significance for me. Please forgive my boldness and my boring you with the problems that I face. If I dare bother you it’s only because there is nobody here whom I could trust intellectually so much. I shall be very grateful for your reply. 40 Yours sincerely, Beata Polanowska-Sygulska 1 Isaiah Berlin, “Does Political Theory Exist?,”in: The Proper Study of Mankind, ed. Henry Hardy (London: Chatto & Windus, 1997), p. 87. 2 Isaiah Berlin, “Historical Inevitability,” in: Liberty, ed. Henry Hardy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 101 footnote 2. 3 Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, 2 vols. (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984 [1945]) 1: 112. 4 Isaiah Berlin, “Political Theories in the Twentieth Century,” in: Liberty, p. 93. 5 Karl Popper, Unended Quest: An Intellectual Biography (Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1976), p. 116. 6 Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, vol. 1, p. 89. 7 ibid. 8 Isaiah Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” in: Liberty, p. 169 (my emphasis).