Adapting to climate change

advertisement

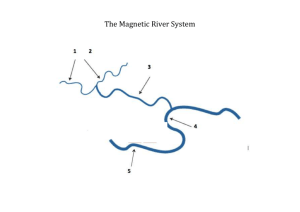

Adapting to climate change – why it matters for local communities and biodiversity: The case of Lake Bogoria catchment in Kenya Musonda Mumba Summary: Climate change is already threatening ecosystems with severe consequences in Africa. Poor people that are dependent on these ecosystems need help to strengthen their capability to adapt to this change. Thus adaptation to climate change is essential and especially for the vulnerable millions. This paper reviews a case study in the Lake Bogoria catchment where WWF has been actively engaged on a project on integrated water resources management. It discusses how the local communities are adapting to climatic variability within the area, indicating the interventions undertaken and providing recommendations and the way forward. Introduction and background Science has provided clear evidence that climate change is real and is happening. Within Africa there is growing acknowledgement that climate change impacts are inevitable. Poor people’s livelihoods are more threatened than ever by this change and thus their ability to adapt to these changes is necessary. In Eastern Africa reliance of communities on land for agriculture, rivers and other natural resources is very high. However, these resources are climate-sensitive and are likely to be affected. Most parts of the region are already water scarce and hence even more vulnerable. Therefore adaptive capacity of the local communities dependent on these resources is very critical1. Its note worthy that non-climate changes may have greater impact on water resources than climate change. Thus climate change presents an additional challenge to water resources management. The impact of climate on water resources not only depends on climate itself but also the characteristics of the system, how the management of that system evolves over time and eventually how it adapts to the change2. The Lake Bogoria case study aims to show how local farming communities in the upper catchment are adapting to climate change following highly variable rainfall patterns and reduced flows in the Waseges River. WWF has recognized the importance of adaptive strategies by local communities and why partnering with various stakeholders is environmentally sustainable especially for water resources which are climate sensitive. Working within the Lake Bogoria catchment – history and objectives Lake Bogoria is one of several rift valley lakes located within the East African Rift Valley (Figure 1). The lake and its wider catchment are rich in natural resources that include the lake itself, forests, wildlife and pastures. The upper catchment comprises forests where the source of the Waseges River (Figure 2) – the main freshwater inflow into the lake – starts. This part of the catchment has multiple land-use practices but mostly small-scale farm holdings where irrigation agriculture is the main practice. The middle and lower catchments on the other hand lie within a semi-arid to arid region where the main land-use practices are livestock production and irrigated agriculture. Originally dominated by nomadic groups, most of the livestock keepers are now sedentary. Both the upper and middle catchments have experienced an increase in population and changes in land-use over the years. Rainfall variability over the years has compounded the problem even further. However, like many agricultural zones of Kenya, the problems are further exacerbated by uncontrolled, illegal over-abstraction from the Waseges River3. These factors clearly have had enormous pressure and effects on the environment and particularly water resources. Figure 1. Location of the Lake Bogoria within the East African Rift Valley. Figure 2. Lake Bogoria National Reserve and its drainage system Approach and intervention – community adaptation strategies to climate change The Waseges River flows down to the middle catchment in Subukia, a semi-arid area with no more than 700 mm per annum. Communities here rely predominantly on irrigated agriculture for food and cash crops for subsistence. The Lari Wendani Irrigation Scheme was initiated by the irrigation department in 1984 as a way of enhancing food security and production. Currently it supports 94 families covering 25 ha. Over the years deforestation and over-abstraction within and upstream of the scheme resulted in less water available for the scheme, and downstream there was sometimes no flow for over 5 months. Working with various partners and stakeholders such as the Department of Irrigation, the Water Resources Management Authority (WRMA), local community based organizations (CBOs), the Water Resources Users Associations (WRUA), WWF engaged with the local communities within the middle catchment to find a solution for better water resources management. The WRUA (Figure 3) was particularly a good entry point as this included different user within the community. The WRUA is a representative group consisting of members of various common interest groups and the community at large whose main interest is to discuss issues related to water. This forum presents itself as an effective medium for participatory management of conflicts that arise from water resource use. In effect the process described above required the use of a nested approach (Figure 4) were participation was from a micro scale (farm level) to the macro scale (basin level). For the purpose of this case study, focus was more at the catchment level were several farmers were engaged. There was general recognition that climate change also had a role to play in the reduced availability of water resources, Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) was deemed as an environmentally sustainable approach with the different stakeholders. Figure 3. Nested approach for water governance at river basin scale Over-abstraction of water from the Waseges River, mostly illegal, inefficient water use, combined with variable rainfall, resulted in reduced to no flows within the river for downstream communities. Based mostly on qualitative and anecdotal evidence, the no flow spell lasted for well over eight years. Due to this, conflicts between the downstream and upstream communities ensued. WWF working with other stakeholders in the area organized some members of the WRUA downstream to meet with members of the WRUA upstream so dialogue could be initiated so as to resolve conflict. Though mandated through the Water Act (2002) to have dialogue, WRUAs were not in a position to initiate this. There was also recognition that climate change had altered water resources availability within the area and some coping strategies were needed at farm and community level. Communities in and around the scheme area through their engagement with WWF and Department of Irrigation were influenced to dig pan dams for water storage and use during the dry period so as to let the river flow. One requirement for getting a water permit is to have 90 day water storage on the farm. The irrigation department in partnership with WWF and the fisheries department provided training and sensitization for the communities within the Lari-Wendani to develop water pan dams on their individual farms then stocking them with Tilapia and cat fish (Figure 5). As an incentive to the farmers the fisheries department integrated fish farming into the activity providing additional income to the farmers. During the rainy season between April and September the farmers can harvest storm flow and stock fish. At the end of the period farmers harvest can fish and use the stored nutrient rich water for irrigation during the dry season (October to March) without interfering with the river. This adaptive strategy by the local communities has had positive consequences for the community and the environment. As a result of this intervention, the Waseges River flowed continuously in August 2007 reaching the Lake Bogoria (Figure 6). One key lesson that has been learnt is that a community-based approach is effective in developing appropriate adaptive strategies especially for vulnerable communities. WWF is therefore working very closely with the local communities within the Lake Bogoria Catchment on issues related to irrigated agriculture and the new National Water Resources Management Strategy (2007-2009) which clearly indicates the need for reserve water within river courses. This refers to the quantity and quality of water needed to meet both basic human and ecosystem needs. The strategy also emphasizes that the reserve needs to be met before water is allocated for other uses. Why adaptation is important: recommendations and way forward This case study takes cognizance of the fact that adaptation is necessary particular within water scarce areas where communities are likely to be most vulnerable. Furthermore it is clear that the local communities need the right and appropriate information about how they should adapt. WWF and the different stakeholders have served as change agents within this catchment, which is an essential element to adaptation. WWF’s approach to environmental sustainability has been to advocate Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) mechanism within this catchment. Both the water and agricultural sectors are climate sensitive and this case study illustrates the need to mainstream climate change adaptation policies into these sectors, something that is still lacking. Information about similar case studies within Kenya has not been forthcoming or known. It is particularly important for both environmental and developmental NGOs and civil society groups to share lessons about community based adaptation. Once such lessons are shared and known, it would be easier to influence governments about the necessary policy changes as regards climate change adaptation. Finally figure 4 below illustrates the importance of linkages between policy, science and local communities. National and international policy structures are important in supporting community adaptation to climate. These can be supported by the best available science and knowledge structures however local communities also need to be linked to such structures4. POLICY SCIENCE Better adaptation to climate change LOCAL COMMUNITIES Figure 4. Making linkages between Policy, Science and Local community engagement in climate change adaptation. Musonda Mumba (mmumba@wwfearpo.org) is currently the Regional Freshwater Programme Coordinator for WWF – Eastern Africa Regional Programme Office (WWFEARPO), based in Nairobi, Kenya. She has been involved in wetland conservation, water resources management and ecological research for over 10 years and is also working on climate change adaptation in the region. In February 2008 she was part of an expedition that climbed Rwenzori Mountain to see the impacts of climate change on the glaciers and consequently water resources in the region. References Burton, I. and May, E., The Adaptation Deficit in Water Resource Management, pages 31 -37. In: Yamin, F. and Kenber M. (eds), Climate Change and Development, IDS Bulletin, 35:3, Brighton, UK, 2004. Mogaka, H., Gichere, S., David, R. And Hirji, R., Climate variability and Water Resources Degradation in Kenya: Improving Water Resources Development and Management. World Bank working paper, No. 69, 2006. Reid, H. and Huq, S., Adaptation to climate change – How we are set to cope with the impacts, An IIED Briefing, London, UK, 2007. Smit, B. and Wandel, J., Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability, Global Environmental Change, 16: 282 – 292, 2006. Yamin, F., Rahman, A. and Huq, S., Vulneranbility, adaptation and climate disasters: A conceptual overview, pages 1 -14. In: Yamin, F. and Huq, S. (eds), Vulnerability, Adaptation and Climate Disasters, IDS Bulletin, 36:4, Brighton, UK, 2005. Notes Smit and Wandel, 2006; Huq, 2007 Burton and May, 2004 3 Mogaka, et al., 2006 4 Yamin, et al., 2005 1 2 Pictures (Fig 3) Discussions held with Water Resources User Association (WRUA) © WWFEARPO/Musonda Mumba (Fig 5b) Releasing fish into a pan dam © WWF-EARPO/Musonda Mumba (Fig 6a) Waseges River flowing continuously after 10 years during the dry season – August 2007 © WWF-EARPO/Musonda Mumba