Technologies of the Gendered Body

advertisement

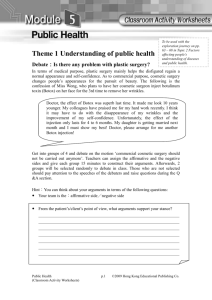

Technologies of the Gendered Body Module Outline 2010-11 Term 2 1 Module outline Term 1 2. Course introduction 3. Gender and the body 4. Technology, feminism and the body 5. Gendered bodies in the media Part II: Disciplining the body 6. Disciplining the body 7. Fighting fat 8. Resisting the “war on obesity” 9. The sporting body 10. Reproductive and genetic technologies Term 2 Part III: Body Modification: (un)natural bodies 11. Body projects 12. Cosmetic surgery 13. Body modification 14. Technologies of enhancement 15. Student presentations 16. Reading week 17. Makeover TV (Lecture: Carol Wolkowitz) Part IV: Rejected bodies 18. Disabled bodies and technologies of normalisation 19. Leaky bodies (caring work) (Lecture: Carol Wolkowitz) 20. Conclusions 23. Revision 24. Revision 2 Term 2 Class Work In addition to the assessed work (as circulated separately), you will be asked to complete two pieces of work this term: A group presentation A 2000 word class essay or short project One 20 minute group presentation: Week 5, Term 2 At the beginning of Term 2, within your seminar groups, you will be divided into groups of 4-5, and working together, you will give a group presentation to the other students on the module in Week 5, Term 2 (using the lecture and seminar times). To prepare for the presentation, you will be asked to collect up to three images, news or magazine articles, advertisements or published materials (e.g. press releases or policy statements) on a topic covered in the module. These could be materials which have a lot in common (for example, a series of ads for a cosmetic surgery clinic), or you could choose contrasting materials (for example, an ad for a weight loss organisation, and a newspaper column written by a size acceptance activist). In the presentation, you will be invited to critically discuss these materials, supporting your analysis with the academic literature that you have read during the module. You might ask, for example: What assumptions about gender, technology and the body are at work in those materials? What do those materials try to communicate about the gendered body and its management? How have those ideas been critiqued? You will get plenty of help and advice in preparing for your presentation, and each group will get written feedback after the presentations. This is important practice and preparation for the assessed project (see below), and will be a good opportunity to develop these skills and learn what is required. However, it is important to note that while you can draw on aspects of your group presentation for your assessed project, you cannot focus on the same published materials, and the final assessed project output needs to clearly be your own work. Class essay or short project The class essay for this term should be handed in at the beginning of the seminar in Week 7. There is a limit of 2000 words. For this class essay, you can EITHER do a shorter version of the project that you will be doing as part of the assessed work (if you are taking the module 50:50 or 100% assessed), OR one of the essay titles below. For the short project, you should critically discuss one image, news or magazine article, advertisement or other published material (e.g. press release or policy statement) on a topic covered in the module. You should support your analysis with reference to the relevant academic literature. Copies of the materials you are using should be appended to the project. Your short class essay project cannot use the same materials as your assessed project, but it can be on the same topic. 3 If you would prefer to do an essay, please choose a title from the list below: 1. Why do people join slimming clubs? 2. Evaluate Nick Crossley’s claim that gym users have moral careers. 3. Critically evaluate the claim that the “war on obesity” is morally, and not scientifically, driven. 4. In what ways are body projects gendered? Illustrate your answer with specific examples. 5. How is the concept of the “body project” useful for thinking about cosmetic surgery? 6. Evaluate the argument that non-normative body modification is empowering. 7. Critically assess Orlan’s claim that the body is no longer adequate for the current situation. 8. To what extent are interventions to “normalise” disabled bodies complicit with problematic bodily norms. 9. Is gender or social class the more central to TV programmes involving the makeover of participants’ embodied selves? 10. Why is the care of ‘leaky bodies’ perceived to be problematic? 4 Week 11: Body Projects In this lecture we take up the notion, implicit in previous lectures, of body projects (the way, that is to say, in which we reflexively work on our bodies for particular ends, goals or purposes). The lecture, as such, involves both a theoretical discussion of the concept of body projects -- evident in the work of writers such as Giddens, Shilling and Crossley -- and some illustrative examples of contemporary body projects and reflexive body techniques. Seminar questions: What is meant by body projects and reflexive modes of embodiment? In what ways are body projects gendered? Key reading: Gill, R, Henwood, K and McLean, C (2005) “Body projects and the regulation of normative masculinity” Body and Society 11 (1) 37-62 Recommended readings: Crossley, N. (2004) The circuit trainer’s habitus: reflexive body techniques and the sociality of the workout. Body and Society. 10 (1): 37-69. Crossley, N. (2005), Reflexive Embodiment in Contemporary Society. Buckingham: Open University Press (Chpt. 9 ‘Mapping reflexive body techniques). Davis, K. (1994) Reshaping the Female Body: The Dilemma of Cosmetic Surgery. London: Routledge. Featherstone, M. (1991) “The body in consumer culture”, in Featherstone, M., Hepworth, M and Turner, B.S. The Body: Social Process, Cultural Theory. London: Sage. Giddens, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity. Cambridge: Polity Press. Monaghan, L (1999) “Creating the ‘perfect body’: a variable project”. Body & Society. 5 (2-3): 267-90. Shilling, C. (2003) The Body and Social Theory (2nd Edition). London: Sage ( Chpt. 1 ‘Intro’ and Afterword) Further readings: Crawford, R (1984) “A cultural account of health: control, release and the social body”, in McKinlay, J.B. (ed.) Issues in the Political Economy of Health. London: Tavistock. Gilman, S. (1999) Making the Body Beautiful: A History of Aesthetic Surgery. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. Lande, B. (2007) “Breathing like a soldier”, in Shilling C. (ed.) Embodying Sociology. Oxford: Blackwell. Monaghan, L. (2001) Looking good, feeling good. Sociology of Health and Illness. 23, (3): 330-56. Shilling, C. (2005) The Body in Culture, Technology and Society. London: Sage (Chpts. 5 ‘Sporting bodies’ and 8 ‘Technological bodies’). 5 Wacquant, L. Body and Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentic Boxer/ Oxford NY: Oxford University Press. Williams, S.J. (2003) Medicine and the Body (Chpt. 8 ‘High Tech bodies’). Williams S.J. and Bendelow, G.A. (1998) The Lived Body. London: Routledge (Chpt 4, ‘The body in high modernity and consumer culture’). 6 Week 12: Cosmetic Surgery Drawing on last week’s lecture on “body projects”, this session will explore the ways in which the phenomenon of cosmetic surgery has been addressed by sociologists. In particular, we will consider the ways in which those undergoing surgery are characterised by others, and how they account for their own decisions to go “under the knife”. Seminar questions 1. In what ways can cosmetic surgery be seen as a “body project”? 2. Why have many feminists expressed concern about cosmetic surgery? Key reading Davis, K (2003) “Surgical stories: constructing the body, constructing the self” in Dubious Equalities and Embodied Differences: Cultural Studies on Cosmetic Surgery Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Recommended reading Balsamo, A (1996) “On the cutting edge: cosmetic surgery and new imaging technologies” in Technologies of the Gendered Body: Reading Cyborg Women Durham; London: Duke University Press Brooks, A (2004) “Under the knife and proud of it: an analysis of the normalization of cosmetic surgery” Critical Sociology 30 (2): 207 Davis, K (1994) Reshaping the Female Body: the dilemma of cosmetic surgery London: Routledge Davis, K (1997) “My Body is My Art” in Embodied Practices: Feminist Perspectives on the Body London: Routledge Davis, K (2003) “Surgical passing: why Michael Jackson’s nose makes “us” uneasy” in Dubious Equalities and Embodied Differences: Cultural Studies on Cosmetic Surgery Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield (or Feminist Theory (2003) 4 (1)) Gilman, S (1999) Making the Body Beautiful: a cultural history of aesthetic surgery Princeton University Press Gimlin, D (2000) “Cosmetic surgery: beauty as commodity” Qualitative Sociology 23 (1): 77-98 Morgan, K P (1998) “Women and the Knife: cosmetic surgery and the colonisation of women’s bodies” in Hopkins, P D (ed.) Sex / Machine: readings in culture, gender and technology Indiana: Indiana University Press Pitts-Taylor, V (2007) Surgery Junkies: Wellness and Pathology in Cosmetic Culture New Brunswick; Rutgers University Press Further Reading Blum, V L (2003) Flesh Wounds: the Culture of Cosmetic Surgery Berkeley: University of California Press Dally, A (1991) Women Under the Knife London: Hutchinson Davis, K (2002) “A dubious equality: men, women and cosmetic surgery” Body & Society 8 (1): 49-65 Davis, K (2003) Dubious Equalities and Embodied Differences: Cultural Studies on Cosmetic Surgery Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield RD119 D26 7 Gagne, P and McGaughey (2002) “Designing women: cultural hegemony and the exercise of power among women who have undergone elective mammoplasty” Gender and Society 16 (6): 814-838 Gilman, S (1998) Creating Beauty to Cure the Soul: race and psychology in the shaping of aesthetic surgery Gimlin, D L (2002) Body Work: Beauty and Self-Image in American Culture Berkeley: University of California Press Greer, G (1999) The Whole Woman London: Doubleday Haiken, E (1997) Venus Envy: A History of Cosmetic Surgery Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press Jacobson, N (2000) Cleavage: technology, controversy and the ironies of the manmade breast London: Rutgers University Press Jones, M (2004) “Architecture of the body: cosmetic surgery and postmodern space” Space and Culture 7 (1): 90-101 Jones, M (2008) Skintight: An Anatomy of Cosmetic Surgery Oxford: Berg Negrin, L (2002) “Cosmetic surgery and the eclipse of identity” Body & Society 8 (4): 21-42 Tiefer, L (2008) “Female genital cosmetic surgery: freakish or inevitable? Analysis from medical marketing, bioethics and feminist theory” Feminism and Psychology 18: 466-479 Urla, J and Swedlund, A C (2000) “The Anthropometry of Barbie: unsettling ideals of the feminine body in popular culture” in Schiebinger, L (ed.) Feminism and the Body Oxford: Oxford University Press Wolf, N (1990) The Beauty Myth London: Chatto & Windus Zimmerman, S M (1998) Silicone Survivors: women’s experiences with breast implants Philadelphia: Temple University Press 8 9 Week 13: Body modification In this session we will be exploring body modification practices (and projects) that violate beauty norms, and consider the competing claims that these practices either reproduce gendered and raced bodily norms, or subvert them. Seminar questions 1. Is body modification a means of reclaiming the female body, or just another means of objectifying it? 2. How do people account for non-normative body projects? How are those accounts different from those of people engaging in normative body projects? Key reading Pitts, V (2003) “Reclaiming the female body: women body modifiers and feminist debates”. Ch. 2 in In The Flesh: the Cultural Politics of Body Modification Houndmills: Palgrave Plus at least ONE of the following recommended readings: Recommended readings Klesse, C (1999) “Modern primitivism: non-mainstream body modification and racialized representations” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 15-38 Pitts, V (1999) “Body modification, self-mutilation and agency in media accounts of a subculture” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 291-303 Pitts, V (2003) In The Flesh: the Cultural Politics of Body Modification Houndmills: Palgrave Sweetman, P (1999) “Anchoring the (postmodern) self? Body modification, fashion and identity” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 51-76 Turner, S (1999) “The possibility of primitiveness: towards a sociology of body marks in cool societies” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 39-50 Further Readings Anderson, C (2004) Legible Bodies: Race, Criminality and Colonialism in South Asia Oxford: Berg Atkinson, M (2003) Tattooed: the Sociogenesis of a Body Art Toronto: University of Toronto Press Atkinson, M (2002) “Pretty in ink: conformity, resistance and negotiation in women’s tattooing” Sex Roles 47 (5-6) 219-235 Caplan, E (ed.) (2000) Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History London: Reaktion Books DeMello, M (1993) “The convict body: tattooing among male American prisoners” Anthropology Today 9 (6): 10-13 Deschesnes, M, Fines, P and Demers, S (2006) “Are tattooing and body piercing indicators of risk-taking behaviours among high school students?” Journal of Adolescence 29 (3): 379-393 Fisher, J (2002) “Tattooing the body, marking culture” Body and Society 8 (4): 91107 10 Jeffreys, S (2000) “ ‘Body art’ and social status: cutting, tattooing and piercing from a feminist perspective” Feminism and Psychology 10 (4): 409-429 Kosut, M (2006) “Mad artists and tattooed perverts: deviant discourse and the social construction of cultural categories” Deviant Behavior 27 (1): 73-95 Riley, S and Cahill, S (2005) “Managing meaning and belonging: young women’s negotiation of authenticity in body art” Journal of Youth Studies 8 (3): 261279 Sanders, C (1990) Customizing the Body: The Art and Culture of Tattooing Philadelphia: Temple University Press Shildrick, M (1999) “This body which is not one: dealing with differences” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 77-92 Van Lenning, A (2002) “The system made me do it? A response to Jeffreys” Feminism and Psychology 12 (4) 546-552 11 Week 14: Technologies of Enhancement Continuing the theme of ‘technologies of the self’, in this session, we will explore technologies which are oriented towards “enhancing” the body’s capacities. Drawing examples from sport and medicine, and with particular reference to the concept of the “cyborg”, we will be asking what “enhancement” is and what challenges it poses to categories of normal / abnormal and natural / unnatural embodiment. We will ask what social structures of inequality are exposed through a focus on enhancement technologies, what assumptions are at work in those practices, and what (potential) impacts those technologies (both imagined and in reality) have on both sociality and subjectivity. Seminar questions 1. What are “technologies of enhancement”? 2. Is enhancement cheating? 3. In what ways do technologies of enhancement disrupt the categories of normal/abnormal and natural / unnatural? How do they reaffirm those categories? 4. How useful is the concept of the cyborg for thinking about technologies of the gendered body? 5. Donna Haraway says that she would rather be cyborg than a goddess? Do you agree? Key reading Hogle, L (2005) “Enhancement technologies and the body” Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 695-716 Recommended reading Balsamo, A (1999) Technologies of the Gendered Body: Reading Cyborg Women Durham: Duke University Press (esp. Ch 1: Reading cyborgs, writing feminism: Reading the body in contemporary culture). Conrad, P and Potter, D (2004) “Human growth hormone and the temptations of biomedical enhancement” Sociology of Health and Illness 26 (2): 184-215 Gane, N (2006) “When we have never been human, what is to be done? Interview with Donna Haraway” Theory, Culture and Society 23 (7-8): 135-15 Haraway, D (1991) “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, technology and socialistfeminism in the late twentieth century”. In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: the Reinvention of Nature New York: Routledge; OR in Hopkins, P D (ed) (1998) Sex/Machine: Readings in Culture, Gender and Technology Bloomington: Indiana University Press (ch. 25). Karpin, I and Mykitiuk, R (2008) “Going out on a limb: prosthetics, normalcy and disputing the therapy/ enhancement distinction” Medical Law Review 16: 413-436 Parens, E (1998) “Is better always good? The enhancement project” Special Supplement to the Hastings Centre Report January-February 1998 Further reading Anderson, W T (2003) “Augmentation, symbiosis, transcendence: technology and the future(s) of human identity” Futures 35: 535-546 12 Ayers, R (1999) “Serene and happy and distant: an interview with Orlan” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 171-184 Butryn, T (2003) “Posthuman podiums: cyborg narratives of elite track and field athletes” Sociology of Sport Journal 20 (1): 17-39 Clarke, J (1999) “The sacrificial body of Orlan” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 185-207 Degrazia, D (2000) “Prozac, enhancement and self-creation” Hastings Center Report 30 (2): 34-40 Elliott, C (2004) Better Than Well: American Medicine Meets the American Dream New York: WW Norton Farnell, R (1999) “In dialogue with “posthuman” bodies: interview with Stelarc” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 129-147 Frank, A (2003) “Surgical body modification and altruistic individualism: a case for cyborg ethics and methods” Qualitative Health Research 13 (10) 1407-1418 Fukuyama, F (2002) Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution London: Profile Books Goodall, J (1999) “An order of pure decision: un-natural selection in the work of Stelarc and Orlan” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 149-170 Gray, C H (ed.) (1995) The Cyborg Handbook London: Routledge Gray, C H (2001) Cyborg Citizen: Politics in the Posthuman Age London: Routledge Hayles, N K (2006) “Unfinished work: from cyborg to cognisphere” Theory, Culture and Society 23 (7-8): 159-166 Henwood, F, Kennedy, H and Miller, N (2001) Cyborg Lives? Women’s Technobiographies York: Raw Nerve Books Katz, S and Peters, K R (2008) “Enancing the mind? Memory medicine, dementia and the aging brain” Journal of Aging Studies 22: 348-355 Kirkup, G, Janes, L, Woodward, K and Hovenden, F (2000) The Gendered Cyborg: A Reader London: Routledge Lupton, D (1999) “Monsters in metal cocoons: ‘road rage’ and cyborg bodies” Body and Society 5 (1) 57-22 McKibbin, B (2004) Enough: Genetic Engineering and the End of Human Nature London: Bloomsbury Miah, A (2003) “Be very afraid: cyborg athletes, transhuman ideals and posthumanity” Journal of Evolution and Technology Vol 13 (http://jetpress.org/volume13/miah.htm) Pitts-Taylor, V (2007) Surgery Junkies: Wellness and Pathology in Cosmetic Culture New Brunswick; Rutgers University Press Plant, S (1998) Zeros and Ones London: 4th Estate Roache, R (2008) “Enhancement and cheating” Expositions 2 (2): 153-156 Schermer, M (2008) “On the argument that enhancement is ‘cheating’” Journal of Medical Ethics 34: 85-88 Shabot, S (2006) “Grotesque bodies: a response to disembodied cyborgs” Journal of Gender Studies 15 (3): 223-235 Shilling, C (2005) The Body in Culture and Society London: Sage (Ch. 8: Technological Bodies). Stelarc (1999) “Parasite visions: alternate, intimate and involuntary experiences” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 117-127 Thacker, E (1999) “Performing the technoscientific body: RealVideo surgery and the Anatomy Theater” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 317-336 Thrift, N (2006) “Donna Haraway’s dreams” Theory, Culture and Society 23 (7-8): 189-195 13 Toffoletti, K (2007) Cyborgs and Barbie Dolls: Feminism, Popular Culture and the Posthuman Body London: I B Taurus Wolmark, J (1999) Cybersexualities Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Zurbrugg, N (1999) “Marinetti, Chopin, Stelarc and the auratic intensities of the postmodern techno-body” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 93-115 Zylinska, J (2002) The Cyborg Experiments: the Extensions of the Body in the Media Age London: Continuum 14 Week 15: Presentations The lecture and seminar times for this week will be used for the group presentations. Week 16: Reading week 15 Week 17: Makeover TV (Carol Wolkowitz) TV reality show personal makeovers debuted on prime time television in 2001, to be followed by other programmes offering more extreme and intrusive remedies for perceived defects in embodied self-presentation. Such programmes demonstrate, first of all, the centrality of contemporary media to pressures to improve the self. They also offer numerous examples of the exacting discipline required to maintain a properly gendered body, and they can also be argued to link gendered presentation to class and other wider ideological forces. Such makeover programmes also raise, and not for the first time, the question of whether we should see female (consumer) culture as a source of pleasure or oppression, autonomy or normalisation. Seminar questions 1. To what extent and in what ways does the personal makeover TV programme represent a new departure? 2. What is meant by disciplinary power? How does it apply to reality TV makeover programmes? 3. Are reality TV programmes as much to do with demonstrating the cultural capital carried by the classed body as gendered self-presentation? Key readings “Reality Television: Fairy Tale or Feminist Nightmare” (2004) Feminist Media Studies 4 (2). A set of very short papers edited by Moorti and Ross. The key reading is the short essays by Moorti and Ross; Wood and Skeggs: Allatson; Deery and Meyer and Kelly. Recommended readings Recommended readings on televised reality programmes Banet-Weiser, S. and K. Portwood-Stacer (2006) “’I just want to be me again!’: Beauty Pageants, Reality Television and Post-feminism” Feminist Theory 7 (2): 255-272. (Can be borrowed from CW) Clarkson, J. (2005) “Contesting Masculinity’s Makeover: Queer Eye, Consumer Masculinity, and ‘Straight-Acting’ Gays” Journal of Communication Inquiry 29: 235-255. Gill, R. (2007) “Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10(2); 147-166 Lewis, T. (2007) “’He Needs to Face his Fears with these Five Queers’: Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, Makeover TV, and the Lifestyle Expert” Television & New Media 8 (4): 285-311. McRobbie, A. (2004) “Notes on What Not to Wear and Post-feminist Symbolic Violence’ in L. Adkins and B. Skeggs (eds) Feminism after Bourdieu Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 99-109. 16 . Recommended readings on other aspects of the (re)making of gendered embodied self-presentation: Coward, R. (1984) Female Desire London: Paladin. Entwhistle. J. and E. Wilson (eds) (2001) Body Dressing Oxford: Berg. See especially J. Entwhistle, ‘The Dressed Body” and H. Radner, “Embodying the Single Girl in the 1960s” Gimlin, D. (1996) “Pamela’s Place: Power and Negotiation in the Hair Salon” Gender and Society 10 (5): 505-26. Gimlin, D. (2002) Body Work: Beauty and Self-Image in American Culture Berkeley: University of California Press Radner, J. (1995) Shopping Around NY: Routledge. Preface and Chapter 5 Speaking the Body: Jane Fonda’s Workout Book. Theoretical background: Bartky, S. (1990) “Foucault, Femininity and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power” in Bartky, S. Femininity and Domination NY: Routledge. Also available in L. Diamond and L. Quinby (eds) (1988) Feminism and Foucault Boston: Northeastern University Press. Bartky, S. (1990) “Foucault, Femininity and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power” in Bartky, S. Femininity and Domination NY: Routledge. Also available in L. Diamond and L. Quinby (eds) (1988) Feminism and Foucault Boston: Northeastern University Press. Skeggs, B. (2004) “Exchange, Value and Affect: Bourdieu and the ‘Self’” The Sociological Review 52 (2): 51-95. Or Chapter 5 in L. Adkins and B. Skeggs (eds) Feminism after Bourdieu Oxford: Blackwell. Skeggs, B. (2002) “Technologies for telling the reflexive self” in Qualitative Research in Action, ed. By T. May, pp. 340-74. London: Sage. 17 Week 18: Disabled bodies and technologies of normalization In this session, we will be exploring some of the technological / social interventions designed to “normalise” disabled bodies. Drawing on a range of examples - including facial surgery on children with Downs Syndrome, cochlear implants for deaf children, genetic technologies of selection, the separation of conjoined twins, the medical management of intersexed children – we will explore what these cases can tell us about the categories of normal / abnormal, and think about how this challenges some of the prevailing assumptions about (un)acceptable bodies. Seminar questions 1. Why do attempts to have a deaf / Deaf child cause so much concern? 2. Kathy Davis argues that facial surgery on Downs Syndrome children raises a problem of inauthenticity – what does this mean? How does this affect how we think about more mainstream cosmetic surgery? Key reading Davis, K (2003) Dubious Equalities and Embodied Differences: Cultural Studies on Cosmetic Surgery Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield (Chapter 7: A Dubious Equality) Recommended Readings Davis, D (1997) “Cochlear implants and the claims of culture? A response to Lane and Grodin” Kennedy Institute of Ethics 7 (3): 253-258 Dreger, A D (2004) One of us: conjoined twins and the future of normal London: Harvard University Press Fausto-Sterling, A (2000) Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality London: Basic Books Lane, H and Grodin, M (1997) “Ethical issues in cochlear implant surgery: an exploration into disease, disability and the best interests of the child” Kennedy Institute of Ethics 7 (3): 231-251 Shildrick, M (1999) “The body which is not one: dealing with differences” Body and Society 5 (2-3): 77-92 Wendell, S (1996) The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability London: Routledge Further Readings Barton, L and Oliver, M (eds.) (1997) Disability Studies: Past, Present and Future Leeds: The Disability Press Corker, M (1997) Deaf and Disabled, or Deafness Disabled? : Towards a Human Rights Perspective Buckingham: Open University Press Davis, L (1997) The Disability Studies Reader London: Routledge Franklin, S and Roberts, C (2006) Born and Made: An Ethnography of Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis Princeton: Princeton University Press Glover, J (2006) Choosing Children: Genes, Disability and Design Oxford: Clarendon Press Grealy, L (1995) Autobiography of a Face New York: Harper Perennial Green, S E (2003) “What do you mean, ‘What’s wrong with her?’: stigma and the lives of families of children with disabilities.” Social Science and Medicine 57: 13611374 18 Hubbard, R (1997) “Abortion and disability: who should and who should not inhabit the world”. In Davis, L (ed) The Disability Studies Reader London: Routledge Hughes, B (2000) “Medicine and the aesthetic invalidation of disabled people” Disability and Society 15 (4): 555-568 Jones, RB (2000) “Parental consent to cosmetic facial surgery in Down’s Syndrome”. Journal of Medical Ethics 26: 101-2 (http://jme.bmjjournals.com) Kerr, A and Shakespeare, T (2002) Genetic Politics: from Eugenics to Genome Cheltenham: New Clarion Press Lane, Harlen (1997) ‘Constructions of Deafness’, in Lennard J. Davis (ed), The Disability Studies Reader, Routledge: New York and London Rapp, R (1999) Testing Women, Testing the Foetus: the Social Impact of Amniocentesis in America New York: Routledge Shakespeare, T (ed.) (1998) The Disability Reader: Social Science Perspectives London: Continuum Books Vanezis, P (2002) “Saving faces: art and medicine working together” The Lancet 359: 267 19 Week 19: Leaky bodies and their care In focusing on the often intrusive and disciplinary technologies of the gendered body, we should be careful to remember the forms of ‘body work’ on which disabled and ill people depend. In these cases much body work is devoted to maintaining, rather than transforming, the client. Care of the elderly, in particular, is often conceptualised as a form of ‘dirty work’ because it involves dealing with an open body that is not in control of its body orifices or ‘leakiness’. What this means for the cared-for individual, as well as those who care for her or him and the relationship between them, needs to be integrated into our overall concern for the practices of the body in contemporary society. Widding Isaksen suggests that care of the leaky body is defined as woman’s work because of meaning of leakiness in our society, while Anderson critiques the recruitment of migrant women specifically do this kind of work. Seminar questions 1. What is meant by the “leaky body”? How is it linked to gender ideology? 2. Why is care of the elderly or disabled so often assigned to racialised, migrant or other low-status workers? Key Readings Widding Isaksen, L. (2002) “Masculine dignity and the dirty body” NORA 10 (3): 137-146. Recommended readings Anderson, B. (2000) Doing the Dirty Work?: The Global Politics of Domestic Labour Zed/ Especially Chapter 2. Ehrenreich, B. and A.R. Hoschschild (eds) Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy London: Granta Books. Especially the articles by Hochschild and Rivas. Gimlin, D. (2007) “What is body work? A Review of the Literature” Sociological Compass 1 (1): 353-370. Isaksen, Lise Wilding (2005) “Gender and Care: The Role of Cultural Ideas of Dirt and Disgust” in Morgan. D. and B. Brandth (eds) Gender, Bodies, Work London: Ashgate. Isaksen, L.W. (2000) “Towards a Sociology of (Gendered) Disgust: Perceptions of the Organic Body and the Organization of Care Work” Berkeley: Centre for Working Families. Accessed at http://wfnetwork.bc.edu/Berkeley/papers/po2.pdf on 6 March 2006. Or Journal of Family Issues, 29 (7): 791-811. Jervis, L.L. (2001) “The Pollution of Incontinence and the Dirty Work of Caregiving in a US Nursing Home”, Medical Anthropology Quarterly 15 (1): 84-99. 20 Lawton, J. (1998) “Contemporary hospice care” Sociology of Health and Illness 2 (2): 121-43. Longhurst, R. (2001) Bodies: Exploring Fluid Boundaries London: Routledge. Price, J. and M. Shildrick (eds) (1999) Feminist Theory and the Body: a Reader Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Murcott, A. (1993) 'Purity and Pollution: Body Management and the Social Place of Infancy' in S. Scott and D. Morgan (eds) Body Matters London: Falmer Press. Twigg, J. (2000) “Carework as a Form of Body Work” Ageing and Society 20(4): 389-41. Twigg, J. (2006) The Body in Health and Social Care Palgrave Macmillan Wolkowitz, C. (2006) Bodies at Work London: Sage. Chapter 7 Body Work as Social Relationship or as Labour’ OR C. Wolkowitz (2002) “The Social Relations of Body Work” Work, Employment and Society 16 (3): 497-510. Wolkowitz, C. (2007) “Dirt and its Social Relations” in B. Campkin and R. Cox, (eds) Dirt: New Geographies of Cleanliness and Contamination London: I.B. Tauris. 21 Week 20: Conclusions Weeks 23-24: Revision 22