lecture outline

advertisement

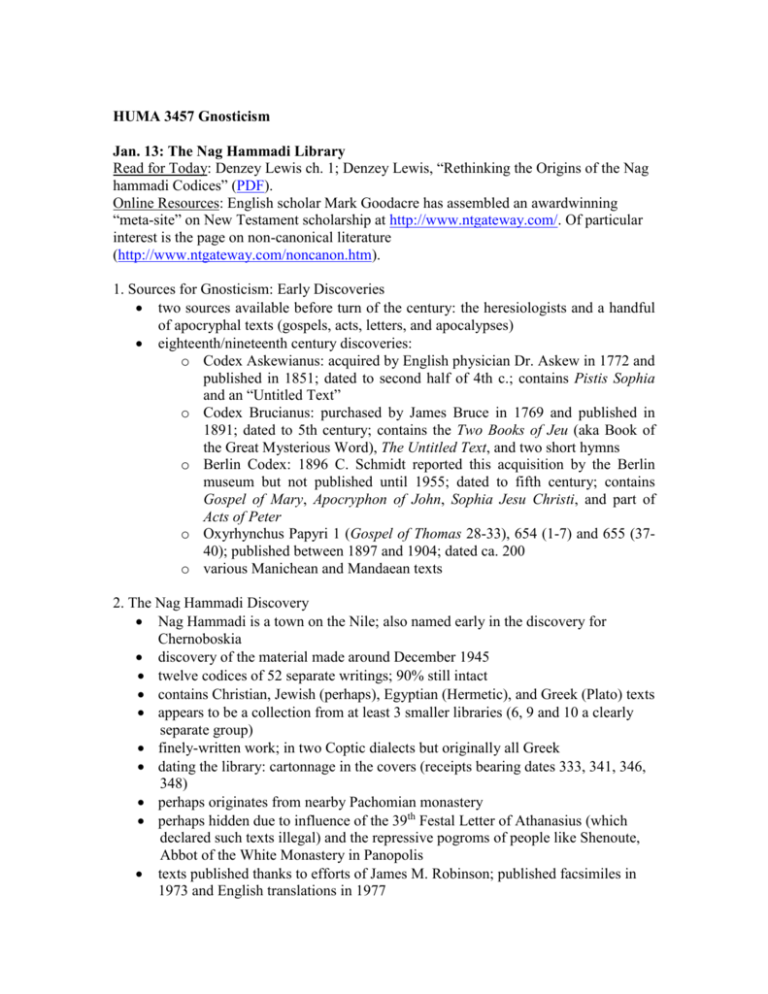

HUMA 3457 Gnosticism Jan. 13: The Nag Hammadi Library Read for Today: Denzey Lewis ch. 1; Denzey Lewis, “Rethinking the Origins of the Nag hammadi Codices” (PDF). Online Resources: English scholar Mark Goodacre has assembled an awardwinning “meta-site” on New Testament scholarship at http://www.ntgateway.com/. Of particular interest is the page on non-canonical literature (http://www.ntgateway.com/noncanon.htm). 1. Sources for Gnosticism: Early Discoveries two sources available before turn of the century: the heresiologists and a handful of apocryphal texts (gospels, acts, letters, and apocalypses) eighteenth/nineteenth century discoveries: o Codex Askewianus: acquired by English physician Dr. Askew in 1772 and published in 1851; dated to second half of 4th c.; contains Pistis Sophia and an “Untitled Text” o Codex Brucianus: purchased by James Bruce in 1769 and published in 1891; dated to 5th century; contains the Two Books of Jeu (aka Book of the Great Mysterious Word), The Untitled Text, and two short hymns o Berlin Codex: 1896 C. Schmidt reported this acquisition by the Berlin museum but not published until 1955; dated to fifth century; contains Gospel of Mary, Apocryphon of John, Sophia Jesu Christi, and part of Acts of Peter o Oxyrhynchus Papyri 1 (Gospel of Thomas 28-33), 654 (1-7) and 655 (3740); published between 1897 and 1904; dated ca. 200 o various Manichean and Mandaean texts 2. The Nag Hammadi Discovery Nag Hammadi is a town on the Nile; also named early in the discovery for Chernoboskia discovery of the material made around December 1945 twelve codices of 52 separate writings; 90% still intact contains Christian, Jewish (perhaps), Egyptian (Hermetic), and Greek (Plato) texts appears to be a collection from at least 3 smaller libraries (6, 9 and 10 a clearly separate group) finely-written work; in two Coptic dialects but originally all Greek dating the library: cartonnage in the covers (receipts bearing dates 333, 341, 346, 348) perhaps originates from nearby Pachomian monastery perhaps hidden due to influence of the 39th Festal Letter of Athanasius (which declared such texts illegal) and the repressive pogroms of people like Shenoute, Abbot of the White Monastery in Panopolis texts published thanks to efforts of James M. Robinson; published facsimiles in 1973 and English translations in 1977 grave robbery? “Rethinking the Origins of the Nag Hammadi Codices,” Nicola Denzey Lewis and Justine Ariel Blount, JBL 133.2 (2014): 399-419 (also: Mark Goodacre, “How Reliable is the Story of the Nag Hammadi Discovery?” JSNT 35.4 [2013]: 303-22) 3. Origins of Gnosticism church fathers: the Devil unleashed sorcerers and deceivers to lead the faithful astray Judaism? apocalypticism includes dualism and notion of mystical redemptive knowledge and the righteous vs. the unrighteous; distance between God and humans in series of intermediate worlds occupied by good and evil spirits; negative assessment of the world; Wisdom traditions (Proverbs and Ecclesiastes) Iranian Zoroastrianism? includes dualism, distinction between body and soul Hellenism? includes individualism and universalism, vocabulary (“rest”, earthly realm based on heavenly realm, etc.), downward development of creation from the primal unity of an unknown higher God down to the lower creator god and our world Hellenistic Judaism? Philo of Alexandria Hermeticism? originates in Egypt ca. 1st-2nd c. CE; includes esoteric wisdom with the aim of salvation and the vision of God, an anti-cosmic tendency Greco-Roman mystery religions? particularly Orphism economic and social factors: elite live in Hellenic cities and poor natives in countryside; Gnosticism seems to have taken root in border cities between the East and West, perhaps among displaced, politically impotent middle educated class