paper_3053_38446

advertisement

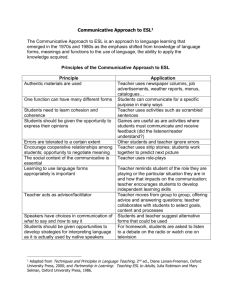

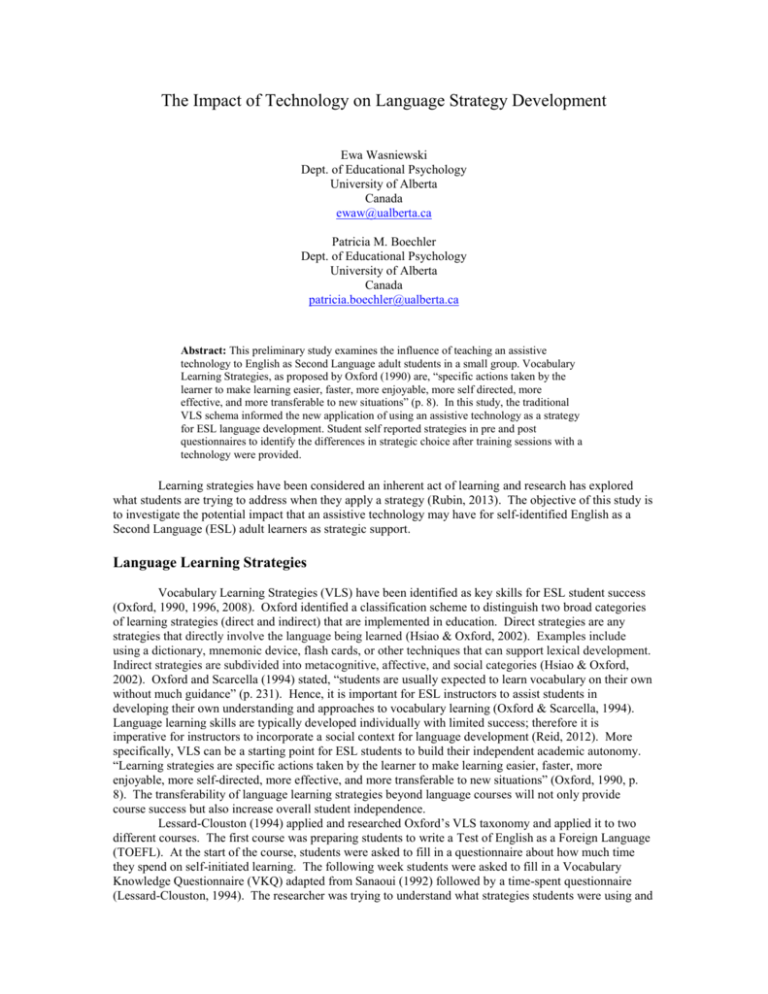

The Impact of Technology on Language Strategy Development Ewa Wasniewski Dept. of Educational Psychology University of Alberta Canada ewaw@ualberta.ca Patricia M. Boechler Dept. of Educational Psychology University of Alberta Canada patricia.boechler@ualberta.ca Abstract: This preliminary study examines the influence of teaching an assistive technology to English as Second Language adult students in a small group. Vocabulary Learning Strategies, as proposed by Oxford (1990) are, “specific actions taken by the learner to make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self directed, more effective, and more transferable to new situations” (p. 8). In this study, the traditional VLS schema informed the new application of using an assistive technology as a strategy for ESL language development. Student self reported strategies in pre and post questionnaires to identify the differences in strategic choice after training sessions with a technology were provided. Learning strategies have been considered an inherent act of learning and research has explored what students are trying to address when they apply a strategy (Rubin, 2013). The objective of this study is to investigate the potential impact that an assistive technology may have for self-identified English as a Second Language (ESL) adult learners as strategic support. Language Learning Strategies Vocabulary Learning Strategies (VLS) have been identified as key skills for ESL student success (Oxford, 1990, 1996, 2008). Oxford identified a classification scheme to distinguish two broad categories of learning strategies (direct and indirect) that are implemented in education. Direct strategies are any strategies that directly involve the language being learned (Hsiao & Oxford, 2002). Examples include using a dictionary, mnemonic device, flash cards, or other techniques that can support lexical development. Indirect strategies are subdivided into metacognitive, affective, and social categories (Hsiao & Oxford, 2002). Oxford and Scarcella (1994) stated, “students are usually expected to learn vocabulary on their own without much guidance” (p. 231). Hence, it is important for ESL instructors to assist students in developing their own understanding and approaches to vocabulary learning (Oxford & Scarcella, 1994). Language learning skills are typically developed individually with limited success; therefore it is imperative for instructors to incorporate a social context for language development (Reid, 2012). More specifically, VLS can be a starting point for ESL students to build their independent academic autonomy. “Learning strategies are specific actions taken by the learner to make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more effective, and more transferable to new situations” (Oxford, 1990, p. 8). The transferability of language learning strategies beyond language courses will not only provide course success but also increase overall student independence. Lessard-Clouston (1994) applied and researched Oxford’s VLS taxonomy and applied it to two different courses. The first course was preparing students to write a Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL). At the start of the course, students were asked to fill in a questionnaire about how much time they spend on self-initiated learning. The following week students were asked to fill in a Vocabulary Knowledge Questionnaire (VKQ) adapted from Sanaoui (1992) followed by a time-spent questionnaire (Lessard-Clouston, 1994). The researcher was trying to understand what strategies students were using and how much time they were spending studying the new language. “On the VKQ, the average score for the class was 63.7%, indicating that many students had learned many of the words they said they had. Overall, the class median score was 70%, suggesting general success among students in their self-stated vocabulary learning,” (Lessard- Clouston, 1994, p. 73). For the second course Lessard-Clouston reproduced the first study with the addition of using the Approach to Vocabulary Learning Questionnaire (AVQ) adapted from Sanaoui (1995) and Lessard-Clouston (1996). The AVQ provided insight into individual participants’ use of VLS. “It is concluded that while more and less successful participants are represented across language backgrounds and approaches to technical vocabulary acquisition, students in academic contexts may nonetheless want to incorporate some structure into their approaches to technical vocabulary learning in order to gain greater depth knowledge of the specialized vocabulary in their field,” (Lessard-Clouston, 2008, p 52). Overall, the researcher noted that the results were mixed about the success of structured versus unstructured courses but did note the need to teach in both dimensions. The research overall indicates that VLS does play a positive role in the lexical development of ESL adult learners. The current study represents a preliminary exploration of the impact of learning a new technology as a strategic tool for direct and indirect language development. Methods Participants for this study were in their first semester of taking the Practical Nurse Diploma for Internationally Educated Nurses (PNDIEN) at a community college. Data was collected from four selfidentified ESL adults registered in the English course as part of the PNDIEN program. The participants moved to Canada from their respective countries within the last five years and had achieved a level 8 on the CLB entrance exam. The purpose of this study was to first identify preexisting strategies that students used in learning a new language. In addition to their regular class time, the researcher provided six one-hour group sessions, which ran throughout the fall semester. The sessions taught how to use the College’s computer system, and then the Read and Write Gold (R&WG) assistive technology program. Data was collected using two questionnaires. The first questionnaire, the Pre-Vocabulary Questionnaire (Pre-VQ) collected information and establish a benchmark of individual participants strategy use. The second questionnaire, the PostVocabulary Questionnaire (Post-VQ) consisted of closed and open questions about the strategic choices the participants made during the study with the addition of two questions about the R&WG program. Results Data collected from both the Pre-VQ and Post-VQ are first reported followed by a comparison of both questionnaires to confirm the differences and similarities of strategies use by the participants over the research period. Table 1. An Overview of Data Collected from the Pre-VQ as Reported by Each Individual Participant Participant Female 1 Student Descriptors: Participants SelfReported Average Time Spent Studying per Week Student Descriptors: Participant Identification of Language Type for Learning Student Descriptors: Participants Identified in which Setting they Acquire Health Care Language Strategies Previously Used by the Participants for English Vocabulary Acquisition Participants Identification of Note Taking Strategies for Studying Purpose Participants Identification of Strategy use for Health Care Vocabulary and if for Class Work or Self Directed Activities 2-3 Hours General Academic Reading and Class 28% Yes, occasional notes on reading and Yes, Class Activities c1ass lecture Female 2 4-5 Hours General Academic Reading and Class 71% Yes, occasional notes on reading and c1ass lecture Yes, Class Activities Male 1 4-5 Hours Health Care Specific Reading and Class 42% Yes, occasional notes on reading and c1ass lecture Yes, Class Activities Male 2 2-3 Hours General Academic Reading and Class 14% Yes, Mental Notes Yes, Class Activities Mean 38.75% Based on the results from the Pre-VQ, participants studied vocabulary between two/five hours per week at the start of this research study. Three fourths of the participants identified that they study using general academic vocabulary language; therefore, it can be inferred that most of the participants have not acquired a working level of language. All of the participants identified that they are only learning the new vocabulary in class or by reading course materials. This could limit the transferability of vocabulary as this limits the participants’ interaction with new vocabulary to the classroom. From a list of seven different strategies, participants were asked to indicate which strategies they use. The seven strategies were; 1) making mental notes, 2) asking an English native speaker, 3) using a paper dictionary, 4) using an individual notebook, 5) applying to writing assignments, 6) using a computer to assist in finding new meaning, and, 7) applying to conversations. Participants indicated they use 38.75% of the strategies listed. This data provided the researcher with an understanding of the strategies that participants have used prior to the study. Table 2. An Overview of Data Collected from the Post-VQ as Reported by Each Individual Participant Participant Student Descriptors: Participants SelfReported Average Time Spent Studying per Week Student Descriptors: Participant Identification of Language Type for Learning Student Descriptors: Participants Identified in which Setting they Acquire Health Care Language Strategies Previously Used by the Participants for English Vocabulary Acquisition Participants Identification of Note Taking Strategies for Studying Purpose Female 1 1 Hour Health Care Specific Outside Involvement 57% Female 2 4-5 Hours General Academic Reading and Class 57% Male 1 1 Hour General Academic Reading and Class 57% Yes, occasional notes on reading and c1ass lecture Yes, I keep detailed written notes Yes, occasional Participants Identification of Strategy use for Health Care Vocabulary and if for Class Work or Self Directed Activities Yes, Class Activities Yes, Class Activities Yes, Class Activities Male 2 2-3 Hours Health Care Specific Reading and Class Mean 43% notes on reading and c1ass lecture Yes, Mental Notes Yes, Class Activities 53.5% The results from the Post-VQ were very interesting because two of the participants identified that they spent less than an hour each week studying new words. One participant reported studying new vocabulary words for about two-three hours per week and the final participant studied four-five hours per week. Comparing these results to the Pre-VQ, two of the participants decreased the time they spent each week studying new vocabulary words. One participant identified that they started to learn more vocabulary outside of the classroom but still benefited from readings and class activities. Overall, the participants used 53.3% of all the possible strategies out of seven possible choices. This is an increase of 17.75% from the Pre-VQ, although a dependent T-test (Wilcoxin) indicated this was not a significant difference, t(4) = 0.141, p < .001. Figure 1. Number of Participants using Each Strategy Pre-VQ and Post-VQ Sessions Figure 2. Bar Graph Representation of Pre-VQ to Post-VQ Strategies Used by the Participants for English Vocabulary Acquisition 60 Percentage out of Seven Strategies 50 40 Pre-VQ 30 PostVQ 20 10 0 Female 1 Female 2 Male 1 Questionnaire Male 2 As demonstrated in the bar graph above, two of the participants increased strategy use over the duration of the term; one maintained strategy use and one decreased strategy use. The original strategies identified on the Pre-VQ were still used and retained by participants as reposted on the Post-VQ. This demonstrates the overlapping nature of strategy use as new strategies overlapped the continued use of the original strategies. Additionally, two specific questions pertaining to the R&WG program were included in the PostVQ. Overall, the participants reported using 32% of seven different R&WG features of the program. Three out of four of the participants identified that they used the features because it was; “time saving,” “understand,” and “learn more.” Secondly, participants were asked to identify which features out of the seven different they used for strategic support. The most used R&WG feature reported by all participants was the text-to-speech feature. Next, half of the participants reported using the speaking dictionary and one fourth reported using the word prediction, pronunciation tutor as well as spelling support features. The homonyms, and fact finder features were not reported to be used at all by the participants. Overall, all of the above figures show the different strategies used by the different participants as reported on the Pre-VQ and the Post-VQ. It can be concluded that the participants increased their strategic awareness and used new strategies to assist with lexical knowledge but the use of a computer, as a strategic support remained constant and needs to be maximized as an educational tool. The feature that best supported students in vocabulary development was the Text-to-Speech feature. Conclusions The findings of this study expand the work of previous researchers in the area of VLS by applying the use of an Assistive Technology as a language strategy. This investigation revealed that ESL adult students would structure their studying and apply technological strategies to acquire lexical knowledge if taught how to use the strategy and how to use the technology. In addition, most students are already using some form of technology to support language acquisition. Further research into the different tools and applications used by adult ESL learners will inform strategic support for differentiated instruction. References Lessard-Clouston, M. (1996). ESL vocabulary learning in a TOEFL preparation class: A case study. Canadian Modern Language Review, 53, 97-119. Lessard-Clouston, M. (2008). Strategies and success in technical vocabulary learning: Students’ approaches in one academic context. Indian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 34(1-2), 31-63. Oxford, R. L. (1990, 1996, 2008). Language Learning Strategies: What Every Teacher Should Know. New York: Newbury House. Oxford, R.L., & Scarcella, R.C. (1994). Second language vocabulary learning among adults: State of the art in vocabulary instruction. System, 22(2), 231-243. Reed, B. S. (2012). Teaching and Researching Language Learning Strategies. By Rebecca L. Oxford. British Journal of Educational Studies, 60(2), 193-194. Rubin, J. (2013). Teaching Language‐Learning Strategies. The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Ruutmets, K. (2005). Vocabulary learning strategies in studying English as a foreign language. Master’s thesis. [online]. Retrieved from http://www.utlib.ee/ekollekt/diss/mag/2005/b17557100/ruutmets.pdf Sanaoui, R (1992). Vocabulary learning and teaching in French as a second language classrooms. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Toronto: University of Toronto, OISE. Sanaoui, R. (1995). Adult learners’ approaches to learning vocabulary in second languages. The Modern Language Journal, 79(1), 15-28. textHELP (2012). Read and Write Gold (Version 8.0) [Computer Software], Antrim: textHELP Systems. (Access date: 5 November 2012).