Art in the Heart of Summer - Sakti (September 17, 2013)

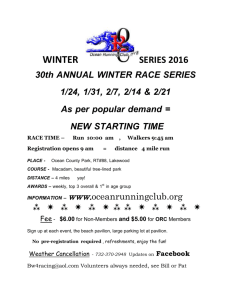

advertisement

September 17, 2013 by artintheheartofsummer Sakti. The Indonesia Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale. The Indonesia Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale is curated by Carla Bianpoen, a Jakartabased art critic, writer and journalist, and independent curator Rifky Effendy. The title “Sakti” originally derives from the Sanskrit word “shak”, which means “to be able”. As the curatorial statement says, Sakti stands for “the sacred force of empowerment or primordial cosmic energy representing the dynamic forces that are thought to move through the entire universe in Hinduism. While of Hindu origin, Sakti was soon integrated into the Indonesian local cosmology and language, and unfailingly indicates magic, divine or supernatural power, the sacred.” 1 Sakti is the traditional divine embodiment of creative energy and power: it is gentle yet invincible, an agent of change and regeneration and of cosmic justice. Sakti is also multi-faceted while at the same time it is a singular essence of truth. As energy it can be conceived as a creative principle, something like ‘the other’ power. 2 In an interview, the curators tell Culture 360 that, Sakti indeed derives from the Hindu belief in Shakti; Sakti in Indonesia denotes various meanings which have integrated with the local culture over hundreds of years. Associated with achieving something beyond human ability. Sakti, among multiple meanings, also connotes change, regeneration and feminine creative energy as opposed to brute strength. The individual artists representing Indonesia in the pavilion use the concept of Sakti to reference and evoke historical, social and cultural peculiarities within the global art discourse. Leading to the exhibition space, is a sort of corridor than runs along the walls of a fake fortress, within which is set the exhibition. Along the walls, there are vertical and horizontal loopholes that give a limited view of what is inside the perimeter. The pathway descends to reach the entrance gate to the fortress. 3 It is interesting to think about the concept of the fortress or castle, the voyage that includes a sort of voyeuristic journey through loopholes, until one reaches the entrance. It’s as if one was peering over an exotic or mysterious place, guarded and hidden from the outside world, but still part of it, as placed in it. Peering through small windows can only heighten one’s curiosity to find out more of what is inside. I think it is peculiar and it hints to something deeply significant, by enclosing the exhibition inside walls so high that one cannot see inside. 4 Only by approaching the gates, one can start seeing something. And it’s even more interesting that the only artwork that is located outside the walls and the gate is something that references political history, depicting “heroes”. Does this layout want to underline the importance of the national presentation, of the national framework and of the national peculiarity of the artists and the exhibition? Let’s have a look at what can be seen inside… 5 The six artists presenting work in the exhibition are Albert Yonathan Setyawan, Entang Wiharso, Eko Nugroho, Rahayu Supanggah, Sri Astari and Titarubi. Albert Yonathan Setyawan Albert Yonathan (b. 1983) received his Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Ceramic Studio at the Faculty of Art and Design, Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) in 2007, and an MA in Visual Arts also at ITB in 2012. He is now pursuing further studies in Ceramic Art at Seika University, Kyoto. The artist uses ceramics as a high conceptual and performative art. His works explore the spiritual dynamics between humans and the natural world, combining hundreds of manually moulded ceramics arranged into patterned configurations. 6 Following geometric formations imbued with an ancient symbolic meaning, they bring a sense of the meditative and the spiritual. Recurrent themes are birds and humans arranged repetitively, while labyrinths appear in circular or rectangular shapes. In October 2012, Albert left for Japan, where he is now pursuing a further studies in Ceramic Art at Seika University, Kyoto. His work for “Sakti”, Cosmic Labyrinth: The Silent Path, is made of 1,200 ceramic objects in the form stupas. The work is also meant as a spiritual meditation in order to find enlightenment through transformative energy, the power of Sakti. 7 Entang Wiharso Entang Wiharso (b.1967) majored in Painting and obtained his BA in Art at the Indonesian Art Institute in Yogyakarta. A painter and a sculptor, his hyper realistic imagery gives the impression of surrealism, as he juxtaposes the past with the contemporary, the imaginative and the real. Entang uses bronze, graphite and aluminium mixed with other materials for his sculptures and installations, interspersed with large paintings. He is inspired by personal and public memory and experiences, Javanese myths and legends, the Candi reliefs, and by popular iconography in which political, social and historical facts and situations are interwoven. 8 His installation for the pavilion, The Indonesian: No Time to Hide, features a large gate covered with reliefs referencing the Borobudur Temple, but depicting contemporary life. “Keep our dreams alive” and “Your perception is not my reality” are the two sentences appearing on the entrance gates. The sculptures around a meeting table outside the fortress have distorted faces of the country’s past and present presidents, which refer to perception versus reality, and to how negative notions of the country are countered by the inner strength of its citizens who stand tall, a feat of Sakti. 9 Eko Nugroho Eko Nugroho (b.1977) graduated from the Painting Department at the Indonesian Art Institute in Yogyakarta. His works are grounded in both local traditions and global popular culture. The imaginary and the real are fused into comics and hybrid images to narrate the happenings of our time. Eko includes craft, such as embroidery and batik, in his artworks. He also reinterprets the old wayang shadow plays, taking actual issues as a theme. 10 Eko extends his art to nurture and reinterpret these branches of culture for the benefit of his art as well as to sustain the livelihood of 24 artists who make the sculptures, embroidery, batik, and puppet theaters. For the pavilion, the artist made Menghasut Badai-badai (Instigating Storms), a bamboo raft with his iconic figures depicted on it, referring to the ability of the country to survive amidst overwhelming political, social and religious challenges, and the struggle to overcome an uncertain present. Sri Astari Sri Astari (b. 1953) studied painting at the University of Minnesota in the United States and at the Royal College of Art, London, but went on to expand into sculpture and installation. Astari is concerned with the re-reading of Javanese traditions, its symbolism and values. Inspired by social and political issues as well as consumerism and lifestyle, she continues to challenge stereotypes and cultural construction, with a tinge of humor, giving new meaning to Javanese traditional symbolism. Her work pays special attention to the position of a woman within her cultural traditions. Recurrent themes have been the kebaya and its accessories, both repressive and protective, and branded bags as a metaphor for modern fetishism. Lately she has given the kebaya new meaning, calling it “armor for the soul”. Her recent works show a more philosophical tendency, highlighting the need to reconcile the self with nature and the universe. 11 Within the Javanese cultural and philosophical realm, Sakti symbolises the power of the South Sea Queen, who’s strength is believed to be behind the Sultan’s power, as well as within each person. This became the artist’s metaphor expressed in the pavilion installation Pendopo: Dancing the Wild Seas with seven Bedoyo dancers. The Pendopo is the fundamental element of Javanese architecture. In the palace there used to be the sacred space where the Sultan was anointed with the South Sea Queen’s invisible presence, power and blessing. In the commoners’ house, pendopo is where visitors are welcomed and ceremonial events are held, a sort of ante chamber. For Sri Astari, it is a metaphor for the soul. To find one’s identity, one has to look intrinsically to find the power that is believed to be present within. According to Astari, it is essential for everyone to “switch on” that power if the human race is to survive beyond materialism. Rahayu Supanggah Rahayu Supanggah earned his PhD from Université de Paris in 1985. He has carried out research and composed numerous pieces based on the various forms of traditional and contemporary music appearing in Asia, and Indonesia in particular. The artist has collaborated with world class artists and theater directors, working alone or as part of a group, at home and internationally. Supanggah holds several prestigious awards, among others, the award of Best Composer at the Asian Film Festival in Hong Kong, the award for World Master on Music and Culture in Seoul, and the Jakarta Academy Award. For the pavilion, he composed “intangible sounds” included in Sri Astari’s installation. 12 Titarubi Titarubi (b.1968) graduated from the Ceramic Studio at the Department of Fine Art, Faculty of Art and Design, Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB). Trained as a ceramist, she has expanded her skills to include sculpture and installations. Titarubi first attracted public attention with her installation of ceramic children’s heads with Arabic inscriptions. Earlier, she had presented an installation dealing with the issue of babies born by in-vitro fertilisation. She then went on to challenge stereotypes and cultural constructions, exploring the position of men and women in society, and experimenting with materials for their impact on defining gender characteristics. She is also inspired by social, political and historical connotations and continues to explore the rich cultural and ethnic heritage of Nusantara, the Indonesian archipelago. 13 For Titarubi, knowledge and science are the pillars of Sakti, which she reveals with the pavilion’s installation The Shadow of Surrender featuring school benches made from burnt wood with thick open books placed on them, a metaphor for education and the length of time and perseverance needed to acquire knowledge. The charcoal drawing, accompanying this installation, of burnt and ashen trees reference the school benches, as well as the cycle of life, death and regeneration (burnt trees in the forest are fertilizers from which new trees will emerge). This cycle of continuity is also revealed within the cut frames for the drawing. The artist juxtaposes the process of acquiring knowledge and science with the colonial past and environmental destruction. 14 MORE about the organisation behind “Sakti” The Indonesia National Pavilion at the 55th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia represents a partnership between Bumi Purnati Indonesia, an independent legal entity established in 2007 and engaged in the performing arts, exhibitions and art consultancy, that also produces national and international cultural events, and Milan-based Change Performing Arts, an independent company that focuses on live performances around the world, including theater, dance, opera, traditional performances, contemporary music and visual art, installations for exhibitions and cultural events in various countries. The pavilion is commissioned by Soedarmadji Jean Henry Damais, an independent scholar with interests in Indonesian art, craft and architecture, active in various foundations and societies for the study and the preservation of Indonesian art and craft, and Achille Bonito Oliva, a recognised and respected Italian contemporary art critic, Professor of History of Contemporary Art at La Sapienza University in Rome and author of many essays on mannerism. While Sakti reflects Indonesia’s rich heritage, it also converges with theme for the 55th International Art Exhibition artistic director Massimiliano Gioni’s concept of “Il Palazzo Enciclopedico/The Encyclopedic Palace,” as is meant to show audiences that contemporary art evolves as the foundation of the creative principle, referencing historical and social aspects as well as the value of local cultural pluralism within the global discourse. (from Sakti press release) All Photographs: “Sakti” installation and artworks views, the Indonesia Pavilion at the 55th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, 2013, Arsenale. Photos: C. A. Xuan Mai Ardia. 15 Texts about the artists and their artworks are drawn from the pavilion’s website, press release and curatorial statements/interviews. http://artintheheartofsummer.wordpress.com/2013/09/17/sakti-the-indonesia-pavilion-at-the-55thvenice-biennale/ 16