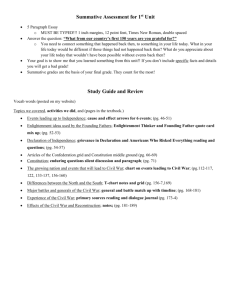

La grande Charte de 1215 et la Déclaration des droits de l`homme

advertisement

The Magna Carta and the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man Bernard Stirn, President of the Section du contentieux, Conseil d’Etat Translated by Eirik Bjorge, Jesus College, Oxford A European Perspective I/ The 1789 Declaration still occupies a prominent place in French law A/ Its presence is a continuing one, explicitly or implicitly Adopted by the Constituent Assembly on 26 August 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man expresses the universal ideas of the philosophy of the enlightenment. ‘One hears’, as Professor Marcel Waline observed, with reference to de la Fontaine’s fable of the oak and the reed, ‘the wind that uproots mighty oaks’. It features in the Preamble of the first French constitution (3 September 1791), which attempted to install a constitutional monarchy. In terms of positive law, it disappeared with the Montagnard constitution adopted by the Convention on 24 June 1793. But it has, according to commissaire du gouvernement Corneille in Baldy (Conseil d’Etat, 10 August 1917), been ‘implicitly or explicitly part of the preamble of all republican constitutions’. It provides that ‘individual liberty is the rule: measures restrictive of rights are the exception’. The presence of the Declaration became explicit again win the preamble of the constitution of 27 October 1946: ‘the people of France … solemnly reaffirm the rights and freedoms of man and the citizen enshrined in the Declaration of Rights of 1789 and the fundamental principles acknowledged in the laws of the Republic’. The preamble of the constitution of 4 October 1958 refers to that of the 1946 constitution, providing in terms that: ‘the French people solemnly proclaim their attachment to the Rights of Man and the principles of national sovereignty as defined by the Declaration of 1789’. B/ It protects fundamental rights as a whole a) Richness of content Principle of individual freedom, of freedom of opinion, ‘even religious’, of freedom of expression and communication. ‘The free communication of thought and opinion is one of the most precious rights of man; every citizen, therefore, may speak, write, and print freely, except in cases of abuse of this right as determined by statute.’ Principle of equality before the law, equality in matters relating to taxation and to public employ. Protection of the right to property, which ‘right is inviolable and sacred’, of which no one can be deprived except in cases of public necessity and against payment of compensation. Fundamental principles of criminal law: presumption of innocence, the principle of legality, necessity and proportionality of criminal punishment, non-retroactivity in criminal law. Right to recourse to and guarantee of rights, in the separation of powers. Article 16: ‘A society that does not guarantee fundamental rights or the separation of powers does not have a constitution.’ b) Strong legal authority The Declaration of 1789 enjoys ‘full constitutional authority’. It applies to situations of which its authors could not have conceived: nationalization and privatization in connection with the right to property, audio-visual and Internet in connection with the freedom of expression. II/ The Declaration of the Rights of Man contributes to the articulation between the constitution and European law A/ The supremacy of the constitution in the national legal order Similar positions taken by the Conseil d’Etat (30 October 1998, Sarran & Levacher), the Cour de cassation (2 June 2000, Pauline Fraisse) and the Conseil constitutionnel (decision of 19 November 2004). The French courts in this connection take the same approach as other European constitutional and supreme courts. The German Federal Constitutional Court, the Italian Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court: HS2 [2014] UKSC 3, [2014] 1 WLR 324, where Lord Neuberger and Lord Mance observed that: ‘The United Kingdom has no written constitution, but we have a number of constitutional instruments’ and Lord Reed made the point that: ‘If there is a conflict between a constitutional principle and EU law, that conflict has to be resolved by our courts as an issue arising under the constitutional law of the United Kingdom’. French law provides for an exception in the application of European law only so far as the incidence of European law might threaten the ‘constitutional identity’ of France: Conseil constitutionnel, 10 June 2004 and 27 July 2006. Application of the rights guaranteed by the EU and by the ECHR: Conseil d’Etat, 8 February 2008 Arcelor and 10 April 2008 Conseil national des barreaux. According to the image of the President of the German Federal Constitutional Court, Andreas Vosskuhle, in his lecture of 31 January 2014, on the occasion of the opening of the judicial year in the European Court of Human Rights, European law is not so much as a Kelsenian pyramid, as Calder’s mobile, whose component parts find their equilibrium by applying force upon each other in perpetual movement. As President Vosskuhle concludes: ‘When everything goes right, a mobile is a piece of poetry that dances with the joy of life and surprises.’ B/ The logics of conciliation The contents of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, the European Convention, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union are largely identical. The interpretation of the Declaration is inspired by European exigencies. The Conseil constitutionnel—in its application of the guarantee of rights, the protection of property, the rules of penal procedure—draws inspiration from European law. Examples : pretrial detention and arbitrary detention. Olivier Dutheillet de Lamothe: ‘dialogue without words’. The growing importance of comparative law in a context where the territoriality quality of law decreases in importance. Series of seminars organized by the Conseil d’Etat in May 2015, in which several British government officials, judges and academics have agreed to participate. The necessity of respecting subsidiarity and the national margin of appreciation European Court of Human Rights, 18 March 2011, Lautsi v Italie: crucifixes in state schools. European Court of Human Rights, 1 July 2014, SAS v France: French law of 11 October prohibiting the concealment of one’s face in public places. European Court of Human Rights, 5 June 2015, Lambert v France: assisted suicide. Non bis in idem European Court of Human Rights, 4 March 2014, Grande Stevens v Italy. Conseil constitutionnel QPC of 18 March 2015.