pragmatics

advertisement

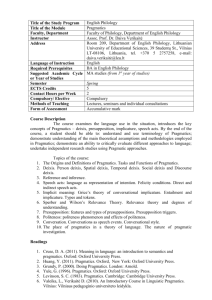

UNIVERSITY OF CRAIOVA FACULTY OF LETTERS DEPARTMENT OF BRITSH AND AMERICAN STUDIES PRAGMATICS Core Course Target population: 4th year students Specialization: Romanian (major) – English (minor), Distance Learning programme Course designer: Senior Lecturer TITELA VÎLCEANU Course description The course focuses on current approaches and methods in the complex field of pragmatics. Apart from the bulk of theory, students are provided seminar tasks or home task assignment in order to understand that pragmatics is concerned with the relation language-user of the language and that communication is embedded in the cultural context. The course basically intends to raise and train linguistic and cultural awareness, i.e. to develop pragmatic competence. Course objectives to make students aware of the status of pragmatics in the framework of linguistic sciences and in the universal frame of human communication; to make students understand that pragmatics is an interdisciplinary science; to expose students to a variety of tasks in order to develop reflective thinking of pragmatic factors in communication Course content 1. The hybrid nature of pragmatics Definitions of pragmatics Towards a unified science 2. Speech Act Theory Austin’s constative vs. performative utterances Felicity conditions Speech-act schema 3. Co-operation and conversational implicature Grice’s Cooperative Principle Conversational Maxims Non-observance of conversational maxims Conversational implicature 4. Strategies of politeness The face management view - positive politeness - negative politeness - face-threat acts typology 5. Presupposition Pragmatic presupposition Presupposition triggers 6. Presupposition features Deixis Person deixis Empathetic deixis Place deixis Time deixis Discourse deixis Social deixis Bibliography Brown, P., Levinson, S.C. 1978. Universals in Language Usage. Politeness Phenomena. Cambridge: CUP Cottom, D., 1998. Text and Culture. The politics of Interpretation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Cruse, A. 2000. Meaning in Language. An Introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics, Oxford: OUP Grice, H.P. 1975. “Logic and conversation” in Cole P., Morgan, J.L. (eds.). Syntax and Semantics 3: Speech Acts. New York Jaworski, A., Coupland, N. 1999. The Discourse Reader, London & New York: Routledge Leech, J. 1983. Principles of Pragmatics, London: Longman Levinson, S.C. 1983. Pragmatics. Cambridge: CUP Levinson, S.C. 2000. Presumptive Meanings. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press Searle, J. 1969. Speech Acts. Cambridge: CUP Vilceanu, T., 2005. Pragmatics. The Raising and Training of Language Awareness, Craiova: Universitaria Watts, R.J., Ide, S., Ehlich, K. (eds). 1992. Politeness in Language. Studies in Its History. Theory. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Grutier Evaluation: 70% formal examination, 30% homework THE HYBRID NATURE OF PRAGMATICS Pragmatics – a blanket term for all kinds of research focused on language and its use in context. We distinguish three fields of investigation of languages. If in an investigation explicit reference is made to the speaker, or, to put it in more general terms, to the user of a language, then we assign it to the field of pragmatics. (Carnap, 1942:9) In the third stage (of its evolution), semantics merges with what one would nowadays call “pragmatics”: word-meaning is now seen as an epiphenomenon of sentence-meaning and speaker-meaning. (Nerlich, [1956],1992: 3) One of the three major divisions of semiotics (along with SEMANTICS and SYNTACTICS). In LINGUISTICS, the term has come to be applied to the study of LANGUAGE from the point of view of the user, especially of the choices he makes, the CONSTRAINTS he encounters in using language in social interaction, and the effects his use of language has on the other participants in an act of communication. (Crystal and Davy, 1985:278-9) […] if our starting point is to be situated at Morris’s level of generality, pragmatics cannot be viewed as another layer on top of the phonology-morphology-syntax-semantics hierarchy, another COMPONENT of a theory of language with its own well-defined object…Nor does it fit into the contrast set containing sociolinguistics, anthropological linguistics, psycholinguistics, neurolinguistics, etc. Rather, pragmatics, is a PERSPCTIVE on any aspect of language, at any level of structure…One could say that, in general, the PRAGMATIC PERSPECTIVE centers around the ADAPTABILITY OF LANGUAGE, the fundamental property of language which enables us to engage in the activity of talking which consists in the constant making of choices, at every level of linguistic structure, in harmony with the requirements of people, their beliefs, desires and intentions, and the real-world circumstances in which they interact. (Verschueren, 1987:5) the study of meaning of linguistic utterances for their users and interpreters a minimal way of distinguishing semantics from pragmatics is to say that semantics has to do with meaning as a dyadic relation between a form and its meaning: “x means y” (e.g. “I’m feeling somewhat ensurient” means “I’m hungry”; whereas pragmatics has to do with meaning as a triadic relation between speaker, meaning and form/utterance: “s means y by x” (e.g. The speaker, in uttering the words “I’m hungry”, is requesting something to eat). However, once the speaker is introduced into the formula, it is difficult to exclude the addressee, since the utterance has meaning by virtue of the speaker’s intention to produce some effect in the addressee. […] Moreover, the speaker’s meaning […] cannot exclude reference to the context of knowledge, both general and specific, shared by the interactants. (Leech and Thomas, 1990:173; 185) […] pragmatics places its focus on the language users and their conditions of language use.This implies that it is not sufficient to consider the language user as being in possession of certain facilities (either innate, as some have postulated, or acquired, as others believe them to be, or a combination of both) which have to be developed through a process of individual growth and evolution, but that there are specific societal factors (such the institution of the famil, the school, the peer group and so on) which influence the development and use of language, both in the acquisition stage and in usage itself. (Mey, 1996:287) […] the study of meaning in interaction (Thomas, 1995:22) Closely related to semantics, which is primarily concerned with the study of word and sentence meaning, pragmatics concerns itself with the meaning of utterances in specific contexts of use. (Jaworski & Coupland, 1999:14) As seen from these definitions, pragmatics takes into consideration the need for training language awareness, for structuring meaning potential. It is an outward-looking discipline, investigating the relevance of language to ordinary people in various situations, searching for motivation (a sort of forensic activity), for individually- and collectively-regulated language behaviour. Language and society interrelate in the conscious use of language which ceases to be a neutral medium for the transmission and receiving of information. Language in use performs several functions simultaneously for example, the informative function is coupled with the phatic (relational) and with the aesthetic functions. Furthermore, pragmatics deals with the subtleties of implied meaning and with inference mechanisms. Meaning is negotiated, constructed, deconstructed and re-constructed inter-subjectively when the speaker and the hearer take turns in the process of communication. There is not only exchange of information, but also cross-fertilization of ideas and speakers and hearers establish a common ground (social togetherness) which guarantees that failure in communication is unlikely to occur1. Pragmatics is committedly quality- oriented to linguistic and social understanding. Metaphorically, we can speak of arenas of language use where users display a wide range of strategies which are in fact the rules of the game. Besides, the context in which the interaction takes place is dynamic, proactive and meaning is continually coordinated due to the particular cluster of the contextual factors. 1 In Searle’s words “what you get is what you expect” The distinction sentence – utterance is of paramount importance at this point. The sentence, the minimal unit of analysis in semantics, is to be defined as an abstract theoretical entity to which truth conditions are assigned, whereas the utterance is a sentence analogue in context. Hence, pragmatics deals with implicature, presupposition, illocutionary force, deixis etc. In other words, pragmatics actualizes both linguistic and extra-linguistic (encyclopaedic) knowledge2. We shall therefore postulate that pragmatics is a hybrid science, an integrated approach, an interdisciplinary project, a linguistic, cultural and social affair. This holistic view is an indicator of the fact that we dissociate from any approach to pragmatics as a science that can be divided into several distinct branches. Let us now examine Crystal’s (1991:271) solution to the problem of setting boundaries; the author proposes the following divisions and admits that we are dealing with borderline cases rather than with clear-cut instances and that such distinctions are inconsistently made: TASKS AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION Enlarge upon the following statements: a) The (linguistic) habitus is, indeed, linked to its conditions of acquisition sand its conditions of use. This means that competence, which is acquired in a social context and through practice, is inseparable from the practical mastery of situations in which this usage of language is socially acceptable. The language token is not a thing with a form and a function. It is a form which functions in context. It has no meaning, but is used to mean.(Monaghan, 1979: 186) b) Having a language is like having access to a very large canvas and to hundreds and even thousands of colors. But the canvas and the colors come from the past. They are hand-me-downs. As we learn to use them, we find out that those around us have strong ideas about what can be drawn, in which proportions, in what combinations, and for what purposes. As an artist knows, there is an ethics of drawing and colouring as well as a market that will react sometimes capriciously, but many times quite predictably to any individual attempts to place a mark in the history or representation or simply readjust the proportions of certain spaces at the margins. Just like art-works, our linguistic products are constantly evaluated, recycled or discarded.(Duranti, 1997:334) c) Rapid growth in communications media, such as satellite and digital television and radio, desktop publishing, telecommunications (mobile phone networks, videoconferencing), e-mail, internet-mediated sales and services, information provision and entertainment, has created new media for language use. It is not surprising that language is being more and more closely scrutinized (e.g. within school curricula and by self-styled experts and guardians of so-called “linguistic standards”), while simultaneously being shaped and honed (e.g. by advertisers, journalists and broadcasters) in a drive to generate ever-more attention and persuasive impact. Under these circumstances, language itself becomes marketable and a sort f commodity and its purveyors can market themselves through their skills of linguistic and textual manipulation.(Jaworski & Coupland, 1999:5) 2 Levinson (1983:21-2) speaks of assorted facts and interpretive dependence on background assumptions SPEECH ACT THEORY Austin (1962) distinguishes between constative and performative utterances. He defines the former as statements that “record or impart straightforward information about the facts” (“The earth is flat”, “It is pouring”), whereas the latter category utterances “do not describe or report or constate anything at all, are not true and false, and the uttering of the sentence is, or part of it, the doing of an action”. E.g. 1. I do (take this woman to be my lawful wedded wife). 2. I name this ship Queen Elizabeth. 3. I give and bequeath my watch to my brother. We are dealing in fact with the uttering of the words of the performative or speech act under particular circumstances (in the course of a marriage ceremony, when smashing a bottle against the stem, when drawing a will). Speech act theory analyses the role of utterances in relation to the behaviour of speaker and hearer in interpersonal communication. A speech act is not an act of speech in the sense of parole (in Saussure’s terminology) or performance (if we adopt Chomsky’s distinction between language competence or knowledge about the language and performance or the actual use of language); it is a communicative activity (locutionary act) connected to the intention of the speakers (illocutionary force) and to the effect(s) they achieve on the hearers (perlocutionary effect). Speech acts bring about a change in the current state of affairs (in the first example, the two persons involved become husband and wife, they have a different marital status now). Austin further discusses the question of appropriate circumstances since the speaker and other participants should also perform some other actions, whether physical or mental. The author postulates “the doctrine of the things that can be and go wrong, i.e. the doctrine of the infelicities” and proposes the following scheme of the felicity conditions to be met for the “smooth or happy functioning of a performative”: A.1. There must exist an accepted conventional procedure having a certain conventional effect, that procedure to include the uttering of certain words by certain persons in certain circumstances and further, A.2. the particular persons and circumstances in a given case must be appropriate for the invocation of the particular procedure invoked. B.1. The procedure must be executed by all participants both correctly and B.2. completely. C.1. Where, as often, the procedure is designed for use by persons having certain thoughts and feelings, or for the inauguration of certain consequential conduct on the part of any participant, then a person participating in and so invoking the procedure must in fact have those thoughts and feelings, and the participants must intend so to conduct themselves, and further C.2. must actually so conduct themselves subsequently. If rules A-B are violated, the act is not achieved while in the C case, the act is performed, but it is insincere, it is an abuse of the procedure. The infelicities related to AB are called misfires and those related to C are termed abuses. When dealing with a misfire, we say that the act is purported (or perhaps an attempt), void or without effect and the procedure is misinvoked. As far as the abuse is concerned, it implies a professed or hollow act, which is not consummated. Performatives fall into two categories: explicit (which include some unambiguous expression also used in naming the act – such as “I bequeath”, “I bet”) and implicit ones. Yet, we normally utter “Go!” instead of “I order you to go!” to achieve the same effect. The explicit performative utterances are assigned a particular formula: - they have a first-person subject; - the have a performative (illocutionary) verb in the present simple tense, the affirmative form; - they contain a second person pronoun which may be preceded by a preposition; - they embed a clause expressing the propositional content of the utterance. E.g. I hereby declare this bridge to be opened. I (hereby) promise you to be there in time. Yet, in face-to-face interactions we do not utter “I hereby declare to love you” as a performative indicating device, but this does not mean that performativity is denied. Instead, we are dealing with a performativity continuum ranging from the conventional speech acts to the non-conventional ones. E.g. You are fired. Thank you for your support. There is a further distinction made by Austin with respect to the kind of action associated to an utterance: locutionary, illocutionary and perlocutionary action. Locutionary action is equated to the mere act of uttering a sentence and meaning what you say (the literal meaning of a sentence). The illocutionary action, i.e. speech act has force (the intended meaning which is to be inferred by the hearer; the extra-meaning which is conventionally associated to the sentence). Perlocutionary action or effect is what you produce on the hearer by saying what you say (at this point language plays a persuasive role and the hearer is manipulated to act in the way intended by the speaker). Consider the following utterance: It’s so hot in here. Locutionary act: It is so hot in here. (Although it is hard to believe that the speaker imparts information to the hearer or that the utterance simply counts as a constative). Illocutionary act: Will you open the window, please? (the utterance really counts as a request). Perlocutionary act: The hearer complies with the request and opens the window. TASKS AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION 1. Identify the locutionary act, the illocutionary act (force) and the perlocutionary effect of the following utterances: a) In an art gallery, Official: Would the lady like to leave the bag here? Woman: No, thank you. It’s not heavy. b) Billy, what do big boys when they enter into a room? c) Would users please refrain from spitting. 2. Comment on the following performatives and their felicity conditions: a) I withdraw my complaint. I plead not guilty. Thank you for your attention. I absolve you from your sins. b) Will you take this woman to be your lawful wedded wife? Absolutely. c) I challenge you to pistols at dawn. I decline to take up the challenge. d) The court finds the accused not guilty. e) Your employment is hereby terminated with immediate effect. CO-OPERATION AND CONVERSATIONAL IMPLICATURE Literature distinguishes between sense (literal meaning) and force (intended meaning), between what is actually said /expressed meaning and the additional implied/intended meaning. H.P. Grice, who developed the pragmatic theory of implicature, worked with Austin at Oxford in the 1940s and 1950s and delivered the William James lectures at Harvard University in 1957. The speaker implies or conveys some meaning indirectly, while the hearer infers or deduces something from evidence. Etymologically, to imply means “to fold something into something else”. The term implicature is used in order to contrast it with logical implication which refers to inferences derived from logical or semantic content. The logical implication relation is: if p, then q. Logically, non-p does not imply non-q. E.g. p: you scratch my back q: I’ll scratch yours p → q: If you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours. Instead, implicature is based on the content of what has been said and on the assumptions about the cooperative nature of verbal exchanges. Grice identifies two sorts of implicature: conventional implicature and conversational implicature; in the former case, the same implicature arises regardless of the context of utterance, whereas in the latter case, the implicature is generated by the context of utterance. E.g. The woman was in her forties, but still attractive. The link word “but” directs us to something that runs counter to the previous statement; this implicature is encoded linguistically. Furthermore, there is the implicature is that a woman in her forties is no longer attractive. E.g. Would you like a drink? No, thanks. I’m driving. The implicature is that a person who is driving should not drink and such implicature is calculated or processed due to the context of utterance. Starting from this example, we can state that communication is a successful process because the participants try to make a fair contribution, because the verbal exchange is governed by the willingness to take part in the process and because speaker and hearer alike try to optimally fit the information they provide to the context, to the direction in which the exchange takes place. In other words, the whole interaction is based on the Principle of Relevance as highlighted by Grice (1975) and further developed by Sperber and Wilson (1986). Let us remember at this stage that the context is a dynamic entity and does not consist of a pre-determined set of assumptions. There are, of course, assumptions that are part of the speaker’s and hearer’s background knowledge and these assumptions establish the common ground (shared assumptions) which secures the success of the ongoing exchange(s). In his famous book “Logic and Conversation” (1975), Grice puts forward The Cooperative Principle (CP) to explain the mechanisms by which people unfold conversational implicature, and to account for the relation between sense and force, between explicit and implicit meaning. Grice’s theory explains how there can arise interesting discrepancies between speaker meaning and sentence meaning. The CP runs as follows: “Make your contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged.” The four conversational maxims are: 1. The maxim of Quantity: Make your contribution as informative as required (for the current purpose of exchange). Do not make your contribution more informative than is required. 2. The maxim of Quality3: Do not say what you believe to be false. Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence. 3. The maxim of Relation: Be relevant. 4. The maxim of Manner: Avoid obscurity of expression. Avoid ambiguity. Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity). Be orderly. Grice identifies a number of characteristic traits of implicatures (contextual effects) which arise from non-observance (whether deliberate or not) of one or several maxims: 1. they are cancellable or defeasible, i.e. by adding some further information it is possible to cancel them, i.e explicitely denied). E.g. A: Would you like some wine? B: No, thanks. I’ve been on whisky all day. A: All right. (The hearer infers that the speaker doesn’t feel like a drink). B: I mean, I’ll stick to whisky. (Thus, the implicature is cancelled or proved to be false by this further specification). 2. they are standardly non-detachable (apart from those derived from the Maxim of Manner that are related to the form of the utterance), i.e. they are attached to the semantic content of what is said, not to the linguistic form. The replacement of a word or phrase by its synonym will trigger a different implicature. E.g. John is a genius. John is a mental prodigy. John is an exceptionally clever human being. John has an enormous intellect. 3 Harnish (1976:362) favours the combination of the first two maxims, arguing that the amount of information that the speaker gives depends on the speaker’s wish to avoid telling something that is not true. He proposes the Maxim of Quantity-Quality: “Make the strongest relevant claim justifiable by your evidence” John has a big brain. (Levinson, 1983:116-7) There will be ironic reading of the utterances that re-state the first one. 3. they are calculable, i.e. it can be shown that the hearer can derive the inference in question starting from the literal meaning of the utterance and from the co-operative principle and the maxims of conversation. 4. they are non-conventional, i.e. they are not part of the conventional meaning of the linguistic expressions that are used (they are not to be found in dictionaries). E.g. Father: Where are the car keys? Mother: Billy is dating Sue tonight. Mother implies that Billy has taken the car. 5. the same linguistic expression can give rise to different implicatures on different occasions (in different contexts of utterance). Therefore, we can speak of a certain degree of indeterminacy; utterances seem to be of a protean nature, multifaceted: E.g. She is a cat. According to context, the utterance can be interpreted as “a mean unpleasant woman”, “very nervous or anxious”, “she likes currying favour with people” etc. Non-observance of the maxims There are five distinct cases of failing to observe a maxim: - flouting a maxim - violating a maxim - infringing a maxim - opting out of a maxim - suspending a maxim Flouting a maxim – the speaker blatantly fails to observe a maxim, not with the intention of deceiving/misleading. There is an additional meaning i.e. a conversational implicature deliberately achieved. 2. Violating a maxim – Grice defines it as the unostentatious non-observance of a maxim. If a speaker violates a maxim he/she “will be liable to mislead” (1975:49). 3. Infringing a maxim – it occurs when a speaker who, with no intention of deceiving, fails to observe a maxim. The non-observance stems from imperfect linguistic performance (imperfect command of language, nervousness, drunkenness, excitement) rather than from a deliberate choice. 4. Opting out of a maxim – by indicating unwillingness to co-operate. in the way the maxim requires. It is very frequent in public life when the speaker cannot, for legal or ethical reasons, reply in the way normally expected. 5. Suspending a maxim – sometimes there are certain events in which there is no expectation on the part of any participants. Suspension of the maxims can’t be culturespecific or specific to particular events. TASKS AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION 1. Show the steps to be followed in calculating the implicature of the utterance below: I saw Robert with a woman at the restaurant. 2. State whether the following examples are cases of observance of the conversational maxims or not. Identify each type. 1. The speaker was a BBC continuity announcer: At the time of recording, all the cast were members of the BBC drama group. 2. I finished working on my face. I grabbed my bag and my coat. I told mother I was going out…She asked me where I was going. I repeated myself. “Out”. 3. A is asking B about a mutual friend’s new boyfriend: Is he nice? She seems to like him. A woman without her man is nothing. Short course managers are required. The old men and women left the room. They don’t smoke and drink. Happily they left. STRATEGIES OF POLITENESS The Basics of the Theory of Politeness Politeness as well as co-operation is fundamental to interpersonal communication. As a linguistic phenomenon, politeness has drawn considerable attention from linguists, sociologists and language philosophers over the last 40 years: Lakoff (1973, 1977), Leech (1983), Brown and Levinson (1978, 1987), Hill et al. (1986), Ide(1989), Fraser (1990) and Gu (1990). Despite the efforts of these practitioners, however, there was little consensus on the nature of politeness and cross-cultural implications. Politeness refers, separately but also jointly, to the following aspects: promotion of harmonious relations, deference, register, politeness as a surface level phenomenon (locutionary act) and politeness as a deep level phenomenon (illocutionary act). Pragmatic approaches to politeness fall into four categories: the face management view (Brown and Levinson); the conversational maxim view (Leech); the conversational contract view (Fraser); the pragmatic scales view (Spencer-Oatey). The face management view Of the various models of politeness which have been advanced, Brown and Levinson’s claims its pancultural validity. The present chapter attempts an elaboration of the concept of positive and negative politeness considering these universal phenomena. At the very foundation of Brown and Levinson’s (1987) politeness theory lies the assumption that speakers in any given language do not just convey information through their language; they use the language to do things. Brown and Levinson suggest that speakers, in face-to-face interactions, actually build relationships. Communication is negotiation of meaning, even if it is not necessarily a conscious act. In fact Brown and Levinson propose that an abstract underlying social principle guides and constrains our choice of language in everyday discourse. Hence we may infer that the term politeness is not used in its conventional sense of having and showing good manners, displaying courtesy and correct social behaviour, but rather it is intended to cover all aspects of language usage which serve to establish, maintain or modify interpersonal relationships. Brown and Levinson theory rests on the assumption that all competent language users have the capacity of reasoning and have what is commonly known as face4. Face is defined as: Something that is emotionally invested, and that can be lost, maintained or enhanced, and must be constantly attended to in interaction. (Brown and Levinson, 1978:66) the public self-image that everyone lays claim to, consisting of two related aspects: - negative face: the basic claim to freedom of action and freedom from imposition - positive face: positive consistent self-image or ”personality” (crucially including the desire that this self-image be appreciated and approved of ) claimed by interactants. (Brown and Levinson, 1987:61) Brown and Levinson’s notion of face follows on from Goffman (1967 [1955]) in using it to denote the desire which everybody has that their self-image will be taken into 4 The term face in the sense of reputation or good name seems to be first used in English in 1876 as a translation of the Chinese term diu-lian in the phrase “Arrangements by which China has lost face”. account in interaction with others (face is linked to the notions of being embarrassed, humiliated or losing face). Brown and Levinson then develop this concept by relating it to Durkeim’s “positive and negative rites” (co-operation vs. distancing) as two basic sides of politeness. …everyone has face and everyone’s face depends on everyone else’s face being maintained, and since people can be expected to defend their face if threatened, and if defending their own to threaten other’s faces, it is in general in every participants’ best interest to maintain each other’s face. (Brown and Levinson, 1978: 66) And, since “aspects of face [are] basic wants (ibid: 62) these definitions may be glossed as “the desire to be unimpeded in one’s actions (negative face) and the desire to be approved of (positive face)” (Brown and Levinson, 1987:13). The authors go further and say that these two kinds of face-want give rise to two corresponding types of interactive behaviour. These are positive politeness strategies and negative politeness strategies. The concept of positive and negative face as universal human attributes and the consequent concept of positive and negative politeness as characteristic of human interaction are also referred to as face dualism. Brown and Levinson construct their interactional model around a model person (MP), one who, from the outset, in addition to demonstrating a command of the language and a rational capability for determining the means needed to accomplish end goals, possesses two basic, somewhat conflicting face-wants (1987:60). The first is to have one’s individual rights, possessions, and territories uninfringed upon (negative facewants) and the second is the want to be respected and liked by other people (positive face-wants). Since the satisfaction of MP’s wants is, to a large extent, dependent on the actions of the others’, it is in the MP’s best interest to develop linguistic strategies that acknowledge and recognize the face wants of the other participants. Conflict can be understood as a potential ingredient of any interaction simply because social interaction by its very nature presupposes an intrusion into another person’s domain, a person who does not often share the same goals, attitudes, interests, beliefs, or values of the speaker. There are acts that we, as speakers, must do and that threaten the wants of another individual. E.g. orders, requests, and threatens threaten the hearer’s negative face acts of criticism, disapproval, and disagreement threaten the hearer’s positive face Speakers can also perform self-threatening acts E.g. the expression of thanks or the acceptance of an offer are acts that impinge on the speaker’s negative face as they impel future obligation Apologies, admissions of guilt, confessions, among other self-humiliating acts, reduce the positive self-image of the speaker. These acts which are inherently threatening to the speaker or hearer become facethreatening acts-FTAs. They are “acts that by their very nature run contrary to the face wants of the addressee and/or the speaker” (1987:65). Figure 1 depicts the types of FTA5: 5 Further suggested reading: Goffman’s (1967), Fraser’s (1981) discussions of apologies; FTA Speaker Face Negative Positive Hearer Face Negative Positive excuse apology request complaint thanking crying compliment boasting When the speaker intends to perform an act that threatens the positive or negative wants of H, S considers strategic balancing options and may choose a redressive one, one that reveals to H that S is attempting to minimize the threat of the act. S may choose the following strategic options demonstrating the highest risk (face loss) or the least risk (face saving). Strategic options in order of increasing face-threat: 1. Do not carry out the FTA at all. E.g. failing to congratulate somebody or to express condolences, etc. 2. Do carry the FTA, but off record, i.e. allowing for a certain ambiguity of intention. Brown and Levinson draw up a list of strategies for performing off-record politeness: give hints, association clues, presuppose, understate, overstate, be ironic, be ambiguous, be vague, use ellipsis etc. E.g. The soup is a bit bland. I’ve got that terrible headache again. Boys will be boys. Husbands sometimes help to wash up. 3. Do the FTA on record with redressive action (negative politeness). This will involve reassuring the H he/she is being respected by expressions of deference and formality, by hedging, maintaining distance, etc. Brown and Levinson identify several strategies: be conventionally indirect, question / hedge, be pessimistic, give deference, minimize the size of imposition, apologize, impersonalize the speaker and the hearer, nominalize, etc. E.g. I wonder if you know the truth. You must be very busy, but I need your help. Excuse me, but it is not your turn. The letter must be typed immediately. Manes and Wolfson (1981), Manes (1983) – compliments as FTAs; Owen (1983) – apologies and other remedial work in English, with a framework for cross-cultutal studies Passengers will please refrain from flushing toilets on the train. I’d be eternally grateful if you did that for me. We look forward to dining with you. 4. Do the FTA on record with redressive action (positive politeness). This will involve paying attention to the H’s positive face by, e.g., expressing agreement, sympathy or approval. E.g. I’m pretty sure I’ve seen him before. We are favourably impressed by your performance. I must tell you that I like your dress very much. 5. Do the FTA on –record, without redressive action, baldly. This strategic choice is likely to appear in the following situations: emergency cases, task-oriented situations (instructions), the FTA is in the hearer’s best interest, power differential is great, the speaker decides to be maximally offensive etc. E.g. Mind the step! Yes, you may use the dictionary. Give me your pen. Take care! Have a cake. Politeness strategies have not only verbal realization, but also non-verbal e.g. giving a gift, stumbling, etc Harris (1984) suggests that the disfunction between the institutional status-based requirements of face and the more individual side of face involved in the notion of kindness correlates with on-record vs. off-record strategies of politeness. Three factors are involved /calculated to determine the weight of the FTA: the social distance between H and S, H’s power over S, and the rank of imposition. Positive politeness strategies are addressed to H’s positive face wants and are described as expressions of solidarity, informality and familiarity. E.g. exaggerate interest in H, sympathize with H, avoid disagreement Negative strategies conversely are addressed to H’s negative face and are characterized as expressions of restraint, formality and distancing. E.g. be conventionally indirect, give deference, apologize We are thus confronted with politeness strategies and markers of different status: behaviour strategies (e.g. give deference) are mixed with linguistic strategies (e.g. nominalize) (see Ide, 1989). Some are countable (e.g. intensifiers), some gradable (e.g. nominalization), some can transform a negative into a positive strategy (e.g. contraction and ellipsis). Brown and Levinson interestingly state, however, that ”politeness is implicated by the semantic structure of the whole utterance, not communicated by “markers” or “mitigators” in a simple signaling fashion which may be quantified” (1987:22). TASKS AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION Comment on the following sentences in terms of the Politeness Principle (PP) and of the maxims of politeness: a) A: We’ll all miss George and Caroline, won’t we? B: Well, we’ll all miss George. b) P: Someone’s eating the icing off the cake. C: It wasn’t me. c) - I wouldn’t mind a cup of coffee. - Could you spare me a cup of coffee? d) A: Her performance was outstanding! B: Yes, wasn’t it? A: Your performance was outstanding! B: Yes, wasn’t it? e) A: Do you like these apricots? B: I’ve tasted better. f) Please accept this large gift as a token of our esteem. g) I’m terribly sorry to hear that your cat died. h) This is a draft of chapter 4. Please read it and comment on. i) Basil’s wife is in hospital: You just lie there with your feet up and I’ll go and carry you up another hundredweight of lime creams… j) In a very expensive gourmet restaurant, a notice reads: If you want to enjoy the full flavour of your food and drink you will, naturally, not smoke during this meal. However, if you did smoke you would also be impairing the enjoyment of other guests. PRESUPPOSITION Presupposition may be rightly considered as one of the most controversial concepts in pragmatics. Originally, the term was restricted to reference, but it soon expanded its scope. Presupposition is another type of implicature; unlike conversational implicature which is situated, presupposition is dependent, to a higher degree, on the linguistic form of the utterance. Levinson (1983: 167-8) draws our attention to the two distinct uses of the term presupposition: as an ordinary term and as a technical one. The former is attached to any kind of background assumption against which the utterance makes sense or is rational, whereas the latter is restricted to “certain pragmatic inferences or assumptions that seem at least to be built into linguistic expressions and which can be isolated using specific linguistic tests (constancy under negation)”. As seen from the definition, Levinson is cautious in identifying the nature of pragmatic presupposition. Presuppositions refer and remain constant if the sentences are negated (they survive the negation test). Survival of the negation test distinguishes presupposition from entailment. Let us now focus on more complex sentences: Sue denies that she saw Mary yesterday. Its negation reads: Sue does not deny that she saw Mary yesterday. The presuppositions that hold true under negation are: - There are two identifiable persons Sue and Mary (proper names), respectively; - Sue saw Mary yesterday. And they are triggered by the verb to deny. Therefore, the question arises: What are the linguistic expressions that engender presupposition? Levinson (1983:181-4) discusses Karttunen’s (1973) collection of 31 presupposition triggers6 and considers it “the core of phenomena that are generally considered presuppositional”. In fact, Levinson pleads for a loose definition of presupposition, i.e. presupposition which is not characterised by behaviour under negation alone. In what follows, we shall cater this useful checklist (although in a simplified version): 1. Definite descriptions (Strawson, 1950, 1952): John saw / didn’t see the man with two heads → there exists a man with two heads. 2. Factive verbs (Kiparsky and Kiparsky, 1971): to be aware that, to be glad that, to be proud that, to be sad that, to be sorry that, it is odd, to know, to realize, regret 3. Implicative verbs (Karttunen, 1971b): to be expected to, forget, to happen to, manage, ought to 6 What Stalnaker (1973) calls presupposition requirements 4. Change of state verbs (Sellars, 1954, Karttunen, 1973): cease, stop, finish, begin, start, continue, carry on, take, leave, enter, come, go, arrive 5. Iteratives: to come again, to come back, to return, to restore, to repeat, anymore, another time, before, for the nth time 6. Verbs of judging (Fillmore, 1971a): accuse, criticize 7. Temporal clauses (Frege, 1892) introduced by: before, after, while, since, after, during, whenever, as 8. Cleft sentences (Atlas and Levinson, 1981): 9. Implicit clefts with stressed constituents (Chomsky, 1972, Sperber and Wilson, 1979): Linguistics was/wasn’t invented by Chomsky! 10. Comparisons and contrasts (Lakoff, 1971): She called him a liar and insulted him →To call him a liar is to insult him. Mark is nicer than Tom → Tom is nice. 11. Non-restrictive clauses The president’s daughter, who studies law, is 22. 12. Counterfactual conditions (Type 3) If he had been there, he would have helped her. 13. Questions (Lyons, 1977): alternative questions and WH-questions: Are there students interested in pragmatics? Who is interested in pragmatics? In all the above mentioned cases, constancy or survival under negation is the acid test of presupposition. But there also the projection problem (presupposition behaviour in complex sentences) and the question of defeasibility (presupposition cancellation in certain contexts). Presuppositions are determined compositionally (as a function of their subexpressions) by virtue of the principle that the global meaning is the sum of the meanings of the component parts. The projection problem is doublefold: on the one hand, presuppositions survive in contexts where entailments do not, On the other hand, they disappear in contexts where they are expected to survive. The boy kicked the ball There is a boy The boy kicked the ball. If we negate the sentence, we have: The boy did not kick the ball and The boy kicked the ball does not survive whereas There is a boy survives. Pragmatic presupposition becomes a question of appropriate usage, of some background assumption and common ground against which the utterance makes sense (set of propositions constituting the current context; therefore, pragmatic presuppositions are context-embedded). This common ground account (Stalnaker, 1973) or context selection account (Heim, 1983) of presupposition envisages presupposition as preconditions of situations in which a sentence can be uttered. We should rather speak of common ground dynamics as it can be modified in the course of interaction – utterances are interpreted as context change potentials. They are functions that map an input context (common ground before the utterance is accepted by the hearer) to an output context (common ground after the utterance is accepted by the hearer). Presuppositions define for an utterance whether or not an input context is admissible. It is part of the concept of presupposition that a speaker assumes or pretends that the hearers presuppose everything that s/he presupposes (ideally). If context perceived to be defective, the speaker will try to eliminate discrepancies among the presuppositions (for communicative efficiency). This is the second view endorsed by Stalnaker, namely the dispositional definition of pragmatic presupposition. In fact, during the communicative exchange, clues are dropped about what is presupposed. Lewis (1979) labels this process accommodation since it rescues an utterance from inappropriateness by providing a required presupposition. The principle of accommodation is best summed up in Thomason’s words: Adjust the conversational record to eliminate obstacles to the detected plans of your interlocutor.(Thomason, 1990:344) TASKS AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION 1. Discuss presupposition-related aspects in the following examples: a) It was Mary who called the police. b) I’m sorry I’m late. I had to take my daughter to the doctor. c) Picasso painted crying women. d) The Pope died last night. e) John phoned Mary before he finished his lunch. f) John died before he finished his lunch. g) Marion praised them for storing old wine bottles. h) If Michael invites Susan to the party, he will regret that his wife is coming, too. i) She picked up the young man with a scar on his face. j) Roberta knows that Julia’s friend is rich and handsome. k) I believe that Mr. Smith stopped smoking. l) He forgot paying the phone bill. He forgot to pay the phone bill. m) Even Martin cried. DEIXIS Deixis, from the Greek word deiknyai – to display, to show, is one of the most obvious ways of indicating how the contribution of the context of utterance is actually managed by the speaker. As a pragmatic phenomenon, it is concerned with the linguistic encoding of the context of utterance (speech event). Deixis is often equated to indexicality. In fact, all deictic expressions are indexical (they pick out referents in the real world / extra-linguistic context), but not all indices7 are deictic. Therefore, indexicality has a broader scope, i.e. it covers all phenomena of context sensitivity whereas deixis has a narrower scope, dealing with the linguistically relevant aspects of indexicality. Deixis can be further divided into six types: person deixis, empathetic deixis, place deixis, time deixis, discourse deixis and social deixis. Person deixis It is about deictic reference to the participant role of a referent: speaker, addressee8, bystanders – ratified participants which are neither the speaker nor the addressee. Person deixis is instantiated in the system of personal pronouns (first, second and third person). The first person pronouns – I, we – represents the grammatical encoding of the reference to the speaker(s), the second person pronoun – you- represents grammaticalization of reference to the addressee(s) and the third person pronouns – he, she, they – are the grammatical encoding of reference to bystanders. Furthermore, we distinguish between the inclusive-of-addressee and the exclusive-of-addressee use of the first person plural pronoun we: E.g. United we stand. (President George Bush’s speech on the 11 September events; inclusive we) We shall leave in two hours’ time. (exclusive we) As far as the second person pronoun is concerned, there is the unique form you, which is unmarked for the second person singular and marked for the second person plural. You optionally allows for gestural use: E.g. You can’t teach an old dog new tricks. (symbolical) You have to go there at once. (optionally gestural) Following Ch. Peirce’s distinction among index (a sign based on an existential and contiguity relation with the entity it is a sign of), symbol (a sign which has a conventional relation to the entity it is a sign of) and icon (a sign which resembles the entity it is a sign of) 8 A. Bell (1984) coined the phrase audience design which he defines as the extent to which the speakers accommodate to their addressees. He makes a useful distinction between addressees (ratified participants directly addressed) – auditors (ratified participants, not directly addressed) – overhearers (neither ratified participants nor directly addressed) – eavesdroppers (the speaker is not aware of their presence, so accommodation does not apply to this case) 7 Customarily, the third person referring expressions are regarded as semantically deficient or residual, i.e. their descriptive content does not suffice to identify a referent. In this respect, we can draw a cline of deficiency on which indefinite and personal pronouns are ranked as deficient to the highest degree: E.g. someone, she – the woman – the beautiful woman – Anne In the course of the interaction, participant roles undergo shifts – e.g. turn-taking in conversations, taking the floor at conferences etc. – and the deictic centre (or origo if we feel indebted to Bühler) shifts with them. The deictic centre is organized around the speaker at the place and time of speaking (Coding Time in Fillmore’s terms). Yet, many deictic expressions can be transposed or relativized to some other deictic centre. Reference to the person involved in the speech event also becomes manifest in the use of possessive pronouns and adjectives, and verb conjugation (e.g. English verbs add – s in the 3rd person singular, present simple tense; the verb “to be” displays different forms for different persons; In Romance languages there are different endings attached to verbs when conjugated – e.g. Romanian present tense: eu lucrez, tu lucrezi, el/ea lucrează, noi lucrăm, voi lucraţi, ei-ele lucrează etc). Empathetic deixis It refers to the metaphorical use of deictic forms to indicate attitude, i.e. emotional or psychological distance between the speaker and the referent. Broadly speaking, the demonstrative pronoun this is invested with empathy or solidarity while that indicates emotional distance. However, there are numerous instances when the distinction is neutralized: E.g. This is what I like. But also I like that. (empathy) That man! (distance) Place deixis It can be defined as deictic reference to a location relative to the location of a participant in the speech event, typically the speaker. The grammatical realizations of place deixis are adverbs of place, demonstrative pronouns, spatial prepositions and motion verbs. Denny (1978) proposes the term boundedness to refer to the presence / absence of meaning indicative of a border at the location; expressions such as in there, in here, out there belong to bounded deixis while here and there pertain to unbounded deixis (lack of a defined border). Authors (notably Levinson) identify several frames9 of spatial reference: 9 - intrinsic or pure place-deictic words: the adverbs here and there, the demonstrative pronouns this and there (proximity vs. non-proximity); - absolute: east, west, north, south, upstream, downstream, across river etc; - relative: to the right/left of, behind, in front of, away from, next to etc Goffmann (1967) sees frame as individual conceptualization of the structure within which participants are interacting Levinson (1983: 79 ff.) distinguishes between gestural (as a way of securing the addressee’s attitude to a feature of the extra-linguistic world; pointing at something constitutes an ostensive definition) and symbolical usages of place deictic words. Used symbolically, here indicates “the pragmatically given unit of space that includes the location of the speaker at CT (coding time; see the ongoing discussion)” and gesturally it refers to “the pragmatically given space, proximal to the speaker’s location at CT, that includes the point of location gesturally indicated”. E.g. I’m in Madrid and I love it here. (symbolical) Bring it here. (gestural) Sometimes, there, which is typically distal from the speaker’s location at CT, can serve to indicate proximity to the speaker’s location at CT (e.g. on the phone) or RT (receiving time; e.g. when receiving a letter). Spatial prepositions have deictic and non-deictic values. They are deictic when there is reference to the speaker location: E.g. Billy is behind the tree. (non-deictic) Billy is behind the tree, hiding from me. (deictic) Verbs of motion or come-and-go verbs indicate direction relative to the location of participants, typically the speaker. The verbs belonging to the go class serve to show movement away from the speaker’s location at CT whereas the verbs of the come type gloss as movement towards the speaker’s location at CT. Levinson draws our attention towards the fact that some other time can be involved when performing the movement and he cautiously suggests to use the broader term reference time. E.g. Come to me! (reference time coincides with CT) Go there! (reference time coincides with CT) You can come to see me when I return from England. (reference time does not coincide with CT) Some other verbs of the above mentioned type are: bring, fetch, take etc. The verb come can also indicate not the speaker’s current location but his/her home-base: E.g. I came at 10 o’clock, but you were not at home. Special mention needs to be made of the fact that place deixis always incorporates a time-deictic element (CT) while the converse does not hold true. Time deixis It refers to time relative to a temporal reference point. Typically this is the moment of utterance – what Fillmore (1975, 1997) calls Coding Time (CT) or temporal ground zero as different from the Receiving Time (RT) when there is no temporal deictic simultaneity or there is deviation from the canonical situation of utterance. Time deixis is encoded in adverbs of time, tenses and other deictic expressions (greetings). The basic distinction concerns the use of now – “the time at which the speaker is producing the utterance” or broadly “the pragmatically given span including CT “ (Levinson, 1983: 73-74) – and then as marking departure from the moment when the utterance is produced (anteriority or posteriority). E.g. Do it now! I’m now reading an interesting article on traditions. I was very young then. Then, you’ll have to repeat the procedure. Before discussing the deictic use of the adverbs of time (today, yesterday, tomorrow, Sunday, May, this afternoon, this year, next month etc), it is useful to remember that time is measured in days, months, seasons, years – these temporal divisions are measured against a fixed point of reference (including the deictic centre), being non-calendrical in use or they are used calendrically to locate events in absolute time (non-relationally). For instance, the deictic use of the time adverb today serves to indicate the diurnal span in which the speech event takes place, while calendrically the adverb refers to the span of time running from midnight to midnight. Some other examples include: E.g. I’ll go there this week. – the utterance allows for both a calendrical and non-calendrical interpretation, i.e. it guarantees achievement within the calendar unit beginning on Sunday and including utterance time (CT) or within 7 days from the utterance time. I wrote this yesterday and wanted you to receive it today. – CT and RT are distinct. Starting from this example we can state that today systematically varies reference (the reference of today will be different tomorrow etc). I’ll be back in an hour. (notice on the office door) – the exact time when the person comes back is hard to be guessed as there is no indication of CT and RT are not identical. Tenses are a mixture of deictic temporal distinctions and aspect. Seen in this light, the present tense represents the time span including CT, the past tense is the relevant time span before CT and the future tense is the time span following CT. Tenses are classified into absolute and relative (perfect tenses indicate anteriority to a specified moment of time). Last but not least, greetings function as time-deictic elements since they are timerestricted: Good morning is used in the morning, Good afternoon is used in the afternoon etc. It is worth mentioning that Good morning, Good afternoon and Good evening are uttered only when meeting the addressee whereas Good night is used only as a parting formula. Discourse deixis It concerns deictic references to a portion of the unfolding discourse relative to the speaker’s current location in the discourse (e.g. this chapter, the previous chapter, the next chapter, as mentioned before). This and that are discourse deixis elements (we can speak of a re-categorization of these place-deictic elements which become multifunctional). This refers to the forthcoming portion of the discourse and that: E.g. This is what I’ll tell you. That was the only word she could say in Chinese. Levinson claims that the phenomenon of anaphora should be kept distinct from discourse deixis, although the two are not mutually exclusive. Anaphoric elements refer outside the discourse to other entities by connecting to prior referring expressions: E.g. The British Prime Minister delivered a speech yesterday. Tony Blair / He pointed to the importance of the event. - The British Prime Minister , Tony Blair / He are co-referential expressions (they pick out the same referent in the external world. Pronouns are prototypical exemplars as far as anaphora is concerned. For the sake of distinction, let us mention that cataphora connects to referring expressions that are present later in the discourse: E.g. In front of her, Jane noticed a girl playing with a doll. Discourse markers (anyway, but, therefore, nevertheless, moreover, actually etc) relate a current contribution to the prior portions of discourse (we have already discussed these terms as giving rise to conventional implicature). E.g. She acknowledged his presence but pretended not to. – contrast is thus established between the two portions of the utterance. Social deixis It is concerned with direct or oblique reference to the social status and role of the participants in the speech event. Linguistic encodings of social deixis include honorifics, kinship terms (mother, mum) terms of endearment (My dear, darling, Billy), insults etc. Social deixis falls into two categories: absolute (reference to some social characteristics of a referent apart from any relative ranking of referents e.g. royal we10, editorial we for authorized speakers and Your Honour, Your Majesty, Mr. President , The Honourable Member for authorized recipients – see Fillmore, 1975 ) and relational social deixis (reference to the social relationship between the speaker and the addressee). 10 The distinction between a formal plural form of address and the informal singular form of address is political in nature: there were two Roman emperors in the 4 th century (in Rome and in Constantinople) and the words addressed to one were by implication considered to be addressed to both. It can be said that the plurality of emperors triggered a plurality of the address term TASKS Identify deictic elements in the following utterances and discuss their nature: 1. This one is genuine, but this one is a fake. 2. We cannot afford a holiday this year. 3. Mr. Smith did not attend the meeting on Monday. 4. Ladies and gentlemen (opening address). 5. You can never tell what they are after nowadays. 6. There we go. 7. I was born in London and have lived there ever since. 8. Let’s do it! 9. You are to fasten your seat belts now. 10. I am now working on a Ph.D. 11. Tomorrow is Wednesday. 12. I hurt this finger.