AICP Land Use Law Outline - North Carolina Chapter of the

advertisement

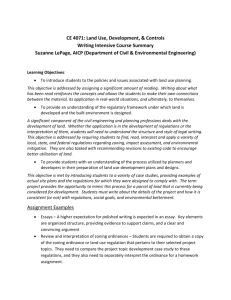

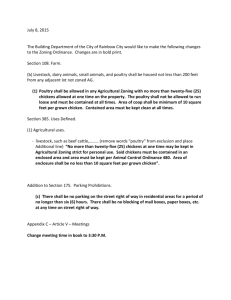

Richard D. Ducker March 2011 Annot. Land Use Outl. LAND-USE LAW: SELECTED TOPIC OUTLINE I. The Legal Bases for Land-Use Controls A. Nuisance Law 1. 2. 3. B. Nuisance: a. An unreasonable interference with rights to the use and enjoyment of land b. Considerations include social values regarding use, the suitability of the use to the area, and the ability of the victims(s) to avoid harm c. Unaesthetic activities generally not nuisances “Per se” or “in fact” a. Per se nuisance: activity, occupation, or structure that is a nuisance under any circumstances regardless of location b. Nuisance in fact: a nuisance because of location, surroundings, or manner of operation Public or private nuisance a. Public nuisance i. Unreasonable interference with right common to public which impairs public health, safety, welfare, or morals ii. Usually continuing over period of time or has produced a permanent effect iii. Nuisance producer generally has to know or have reason to know of effect that nuisance causes iv. Whether victim “comes to the nuisance” is only a factor to be considered v. If use conforms to zoning, the use generally cannot be public nuisance. vi. If public nuisance found, it may be abated or enjoined vii. Unless a statute provides for it, no compensation need be paid for “property” destroyed in abatement since no property interest recognized. See Hadacheck (LPC, p. 23) b. Private nuisance i. Interference without trespass of another person's interest in private use and enjoyment of land ii. Suit may be brought by party that suffers special injuries different in kind from damages suffered by general public iii. Damages is preferred remedy The Police Power 1. 2. The police power (regulatory power) held by the states and is typically delegated to local governments. Delegation comes in several forms: 1 a. 3. 4. 5. C. Enabling authority: State constitution or state statute may authorize local governments generally to exercise certain specific powers. b. Dillon's Rule: Traditionally, and before home rule, the rule of interpretation governing local government power held that the only powers that a municipal corporation may exercise are those expressly granted, those necessarily or fairly implied in or incident to those expressly granted and those essential to the declared purposes of the municipality. c. Home rule: State constitution or state statutes may provide for home rule for certain local governments i. Local government must typically adopt a charter that incorporates or refers to those powers in the constitution or statutes that it may be delegated, but in some cases home rule provisions in the constitution or statute directly grants substantive powers to city. ii. Home-rule city or county given some measure of autonomy in "local" or "municipal" matters but state legislature retains authority over matters of statewide concern. iii. Separate grant by statute of authority to regulate land use may or may not be necessary. Preemption: the law of a higher level of government supersedes or nullifies the law of a lower level of government because the latter conflicts with the former or because there is a need for statewide or nationwide uniformity in regulation. Initiatives and referenda a. In the federal government and in most state and local governments an elected legislative body exercises the legislative power. However, in some states the qualified voters of the state or of a local government may be authorized to exercise legislative power more directly. b. Initiative: a procedure allowing voters to propose or amend a law and then to adopt it as law at a popular election. c. Referendum: a procedure that allows qualified voters to ratify or repeal a legislative action already taken by the elected legislative body. d. If adoption of zoning or other planning legislation is affected by an initiative or referendum, is it subject to the same constitutional and statutory limitations that would apply if the legislative body adopted the law and no initiative or referendum was involved? See City of Eastlake (LPC, p. 21) Improper delegation of legislative power a. Improper delegation to administrative agencies b. Improper delegation to neighbors The Constitutional Framework 1. Substantive Due Process a. Fifth Amendment to U.S. Constitution: "(No person) shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." Made applicable to state and local government by 14th Amendment. b. Regulatory measures must be justified as promoting the public health, safety, morals, and general welfare. Actions may not be arbitrary and capricious and must be reasonable. 2 c. Constitutional test generally requires the following: i. The object of purpose of the regulation must be within the scope of authority of the legislative body and rationally related to a legitimate public process. ii. The means selected to carry out the purpose must be reasonably necessary to its accomplishment. iii. The means selected are unduly oppressive on the individuals affected. d. Federal courts have decreasing interest in substantive due process; the doctrine is stronger and more often applied in state courts. e. See applications of doctrine in Village of Belle Terre (LPC, p. 21) and Moore.(LPC, p. 20) 2. Procedural Due Process a. As a general rule, constitutional due process guarantees apply only to judicial, administrative, and quasi-judicial proceedings, not to legislative decisions b. In general, due process requirements apply when (i) the rights of individuals are affected by the decision substantially more than public at large, and (ii) the party claims a protected property interest or “entitlement,” rather than just an expectancy (a decision requiring the exercise of governmental discretion.) c. Actions of planning boards, boards of adjustment, governing boards, and staff may be subject to due process requirements. d. Legislative actions (such as amending the zoning ordinance in most states) do not require these guarantees and are also accorded a presumption of validity by the courts d. A small, but growing number of states, led by Oregon and Florida, now treat certain zoning map amendments as quasi-judicial in nature, rather than legislative, and thus impose more strict procedural requirements. See Fasano (LPC, p. 22) e. Constitutional procedural due process depends upon nature of the decision but generally includes following elements: i. Adequate and timely notice ii. Opportunity to be heard (may be informal hearing or the trial-type hearing of a quasi-judicial proceeding) iii. If hearing is quasi-judicial, the right to present evidence and crossexamine iv. Opportunity to see, hear, and know all of the statements and evidence considered by decision-making body v. If hearing is quasi-judicial, then decision-making body required to make findings of fact vi. Decision free from conflicts of interest, bias, and the appearance of impropriety vii. Prompt decision viii Complete and accurate record of proceedings 3 3. The "Taking" Issue a. Fifth Amendment to U.S. Constitution: "Private property (shall not) be taken for public use, without just compensation." Provision is made applicable to state and local governments by 14th Amendment. b. Clause applies to use of eminent domain through government purchase of property c. “Public Use Clause” found to allow use of eminent domain to acquire blighted properties through urban redevelopment program to be cleared, replatted, and then resold to private parties in accordance with redevelopment plan. See Berman, (LPC, p. 23). d. “Public Use Clause” found to allow use of eminent domain to acquire properties that are not blighted for clearance and resale to private developers in accordance with a redevelopment plan. See Kelo (LPC, p.1). e. “Taking” can also involve “inverse condemnation” where unintended government action results in physical invasion and occupation. f. “Regulatory taking” can result when regulations that excessively burden or restrict the use of land. g. Traditional approach was for court merely to invalidate regulation that amounted to a "taking." However, in 1987 First English Evangelical Lutheran Church (LPC, p.15) found that U.S. Constitution requires that property owner whose property has been taken also be compensated for "temporary damages" during the period when the regulation was in effect. h. It is never an unconstitutional taking without compensation if government acts to abate or destroy an existing nuisance. Similarly, no taking occurs if a regulation makes unlawful a proposed future use of land if the activity would be a nuisance if established or if principles of real property law would permit the prohibition of such use. See Lucas (LPC, p. 13). For example, a regulation could prohibit the filling of land if the effect of such filling would cause the flooding of neighboring property. In such instances a regulation may be valid even if it effectively eliminates all economically beneficial use of the regulated property. i. It is always an unconstitutional taking without compensation if government acts to physically invade or occupy private property or if a regulation purports to authorize such a physical invasion. For example, regulation might amount to a taking if it purported to authorize planes using a municipal airport to use any necessary airspace over adjacent property properties for landing approaches. j. It is always an unconstitutional taking without just compensation if the prohibited uses are not nuisances under the nuisance exception (see # 3 above), but the regulation effectively deprives the owner of all economically beneficial uses of the land. (See Lucas.) k. If the rules under # 3, 4, and 5 do not apply, then whether a "regulatory taking" without just compensation has occurred depends on the weighing of various interests: i. The nature of the governmental interest (and whether the regulation substantially advances it); ii. The economic impact of the regulation upon the claimant; and iii. The extent to which the regulation has interfered with reasonable investment-backed expectations. The fact that the party claiming a taking bought the property after the regulation was effective does not preclude a taking claim but is a factor to be considered in determining whether the expectations were reasonable. See Palazzolo (LPC, p. 6) l. The economic impact of the regulation may be analyzed more informally by considering the following factors: 4 i. ii. iii. iv. Diminution in value: Does restriction result in significant diminution in value of private property? Confiscation: Does restriction leave owner with a practical use of the property? Average reciprocity of advantage: Though all owners in area are burdened by restriction, do they gain benefit because all land is subject to common restriction? Balancing: Does the harm suffered by the property owner exceed the benefits conferred by the restriction on the public? 4. Equal Protection a. 14th Amendment to U.S. Constitution: "No state shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." State constitutions generally include similar clauses. b. Equal protection requires only that similarly situated people (and their property) be treated in a similar way. c. Principal test is one of classification: i. How carefully is classification made? ii. Is the classification necessary to achieve the objectives of regulation? iii. Is classification too narrow (it is underinclusive), or is it too broad (is it overinclusive)? d. Classification may be made i. Expressly by statute ii. Through the administration of a statute or program iii. In effect (though there generally must be a demonstration of discriminatory purpose) e. Courts now using three tests i. Rational basis test: Court will uphold a classification if it finds a rational basis for its justification. Most classifications in planning reviewed under this test and most are upheld. ii. Strict scrutiny test: Classification applies to a suspect class or burdens a fundamental interest, then government must show compelling interest to justify classification. (Racial classifications are treated as suspect under the strict scrutiny test.) iii. Intermediate test: Courts occasionally use a third test and ask whether the means selected substantially further the purposes of the legislation. f. Applications in land-use regulation i. Setting zone boundaries and regulating locations ii. Difference in requirements for private and public uses of same type iii. Differences in requirements for existing activities and new ones iv. Differences in requirements for similar uses (single-family versus multi-family), especially exclusionary requirements v. Definitions of the term "family" vi. Distinctions based on ownership or tenure vii. Differences in the provision of public services g. U.S. Supreme Court has held in Village of Arlington Heights (LPC, p.20) case that "racially disproportionate impact" of a classification is not necessarily a violation of equal protection. Plaintiff must prove that classification has racially discriminatory purpose. 5. First Amendment a. First Amendment to U.S. Constitution: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of 5 b. c. d. e. II. the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances." It is made applicable to state and local governments by the 14th Amendment. Freedom of religion i. Constitution guarantees "free exercise" of religion and also prohibits the "establishment of religion" See City of Boerne (LPC, p. 7). But see Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000) (RLUIPA), which prohibits a government from placing “substantial burdens” on the free exercise of religion without a “compelling interest.” ii. Land use issues aa. Regulating the location of churches and religious activities bb. Protecting churches from hostile uses Freedom of speech: signs and billboards i. Signs and billboards are a form of protected speech, but are subject to reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions ii. "Commercial speech" entitled to protection if lawful and not misleading, but to extent that political speech is protected iii. Restrictions will be upheld if they only incidentally restrict the freedom of expression in pursuit of aesthetic objectives, so long as local government does not appear to be judging speech on the basis of its content or restricting a form of expression for which there are no adequate alternatives. See City Council of Los Angeles v. Taxpayers for Vincent (LPC, p. 18). Freedom of speech and expression: sex-related businesses i. Sexually oriented adult businesses (e.g., adult book stores, movie houses, topless bars) are forms of commercial speech that are subject to First Amendment protection. See City of Renton (LPC, p.17) ii. Units may disperse such businesses by regulation or concentrate them. However, since restriction is speech-content-related, a more rigorous standard of judicial review is used. Restriction must serve a significant government interest and may not have effect of eliminating this form of expression by excluding it from the community entirely. Zoning focuses on containing “secondary impacts.” Freedom of speech: architectural and design controls i. Architectural expression involves exercise of rights protected by First Amendment since such controls are not unrelated to free expression. The Relation Between Zoning and Planning A. State Planning Legislation 1. 2. 3. Standard Planning Act (proposed by U.S. Dep't of Commerce in 1920's) still evident in state legislation today. But see APA’s Growing Smart Legislative Guidebook,” Stuart Meck, 2002 ed., available on APA website and from Planners’ Bookstore Legislation in many states authorizes the establishment of planning agencies and process. State legislation typically authorizes or compels the adoption of a comprehensive plan with multiple "elements." These typically include a community facilities element, a circulation or transportation element, and a land use element." 6 4. 5. 6. 7. B. III. At least 20 states make planning mandatory for all or some governmental units. these states may or may not require consistency between mandatory comprehensive plan and land use controls. See handout “State Growth Management Programs.” American Law Institute Model Land Development Code (1976) de-emphasizes fixed, end-state planning and encourages continuing planning process with a short-or medium-term program based on both maps and textual policies. Some states elaborate basic planning elements of Standard Act to provide for additional optional or mandatory elements (Calif. requires open space element; Fla. requires economic development element) Some states require plans to address particular problems (Calif: housing element must provide for unit's appropriate share of regional demand for housing) Zoning must be "in accordance with a comprehensive plan" in zoning enabling statutes of most states 1. Standard Zoning Enabling Act included this language, appearing to require conformity with an adopted plan, if one existed. 2. However, commentary to Act suggests different view that zoning must simply by done comprehensively and not in a piecemeal fashion. The "comprehensive plan" is to be found within the ordinance itself. 3. Majority view of courts: preparation of an independently adopted plan is not a condition to the exercise of zoning, and no strict conformity is required even if there is. Some courts have read "in accordance" language simply to mean that ordinance must be the product of a rational process or simply that the ordinance is reasonable. 4. Even in those states with "in accordance" language, courts may look to any adopted comprehensive plan or land use plan for guidance in evaluating zoning and other land use decisions. 5. Zoning must be "consistent" with an adopted comprehensive plan or land use plan in enabling statutes of a small number of states (California, Florida, etc.) a. States that have departed from Standard Zoning Act have adopted more specific requirements tying plan to zoning and other controls like subdivision regulations. b. Of these, most require preparation of a plan; others require consistency only if locals choose to adopt one. 6. The practical problems of consistency requirements a. How does timing of plan relate to regulatory decisions? b. When is a plan adequate and complete? c. How can generality of plan's policies and maps be related to specific nature of regulatory provisions? d. How and how often is the plan amended to conform with ordinances, and vice versa? 7. The plan as a defense by government to a "taking" claim 8. The plan, if not followed, may offer support to a "taking" claim by landowner However, plan designation itself generally found not to have binding effect because it only a guide. Basic Zoning Concepts A. Zoning Districts 1. See "Some Zoning Definitions" in Supplemental Topic Outlines and Lists 7 B. The Jurisdiction of Zoning 1. 2. 3. 4. Extraterritorial zoning and planning. A number of states authorize extraterritorial zoning, planning, and land development regulation that allows cities to adopt extraterritorial zoning without giving residents in the area to right to vote on the ordinance. Such a system apparently does not violate equal protection clause under the U.S. Supreme Court right-to-vote decisions. Zoning of uses of land by state and local government. Some states say such uses (particularly state uses) are absolutely immune from regulation. Other adopt balancing test, balancing the interests of the regulating local government and the State. Still others try to determine the "legislative intent." State-regulated facilities and businesses. Whether zoning applies generally turns on whether legislature intended to preempt zoning, either expressly or by implication. a. Hazardous waste facilities b. Private utilities c. Group homes d. Establishments with liquor licenses Zoning of local government property. Some states apply "governmentalproprietary rule" (governmental uses exempt, proprietary uses subject). Others apply eminent domain rule (use exempt if regulated LG may acquire land by eminent domain). Others apply "superior power test" or "balancing test." C. Nonconformities 1. Feature of property that was legally established prior to the adoption or amendment of zoning 2. One philosophy favors gradual elimination of nonconformities to establish compatible land uses and is based on expansive view of police power. 3. Other philosophy emphasizes the retroactive elimination of a legitimate use and emphasizes the taking clause and the "vested rights" of property owners. 4. Prohibition on expansion a. Intensification generally allowed but not physical expansion b. Repair generally allowed, but not structural alteration c. Nonconformity must go if use abandoned, but courts tend to hold that abandonment must be voluntary. 5. Amortization: requiring conformity after a stated period of time. Majority of courts uphold amortization. Minority of courts restrict amortization to public nuisances (thus generally eliminating amortization for aesthetic reasons). A few find amortization unconstitutional per se. Whether amortization constitutional depends on length of amortization period in relation to owner’s investment and public benefit weighed against loss suffered by owner. Loss depends on initial investment, extent investment recovered, salvage value, length of lease, and provisions for its termination. D. Vested Rights and Estoppel 1. 2. If changes in regulations adopted while development is in progress, is the owner allowed to complete the project under the requirements in effect when he began, or must he comply with the new requirements? Two theories: a. Vested rights approach: Due process protects a property owner whose activities have proceeded so far that it would be unfair to require compliance with the new requirements, or to do so would deprive him of property rights he has already acquired. 8 3. 4. 5. 6. b. Equitable estoppel approach: A unit cannot change its requirements as to a particular property owner if the owner has made substantial expenditures in good faith reliance on some act or omission of the government. What is required to gain protection a. In some states the mere purchase of land in reliance on a rezoning is sufficient. b. In others the approved of a zoning site plan or the granting of a zoning permit is enough. c. Elsewhere a valid building permit is required. d. Older, more traditional rule requiring the applicant to show good faith reliance on the permit by proceeding at a normal pace of development and substantial expenditures made in such reliance. If property owner obtains vested right and unit adopts more restrictive requirements, the use or project may attain nonconforming status. Statutory or ordinance protection may be provided. Development agreements: a. In a small number of states local governments are specifically authorized by state statute to enter into contractual agreements with developers. b. The primary purpose of these agreements is typically to negotiate the exact nature and scope of the developer's vested right to complete a large-scale, multi-phased project. c. The local government is typically authorized to agree that no change in the law adopted subsequent to the agreement will be applied to the project. d. The agreement may also include terms concerning the scheduling and phasing of the project and the exactions that will be imposed upon the developer. E. Zoning Treatment of Specific Groups and Activities 1. Single-family residential use a. Definition of "family" in single-family zoning i. Zoning does not limit number of related family members who can live together but often limits the number of unrelated persons who can. ii. Village of Belle Terre (LPC, p. 21) upheld provision limiting the number of unrelated person living together as a family. iii. But several state courts have invalidated such restrictions, applying strict scrutiny test under equal protection analysis because it infringed fundamental rights of privacy and association under state constitution. b. Group homes as a permitted "family" use i. Tendency of courts to interpret a group home as coming within definition of a family if it is the functional equivalent of a stable family unit. ii. Amendments to federal Fair Housing Act of 1988 make it applicable to discrimination against the handicapped and serve to invalidate restrictions excluding group homes for handicapped, even where number of persons served exceeds cap for unrelated persons. Separation requirements between group homes may also be suspect. However, occupancy standards typically found in minimum housing ordinances may be applied to group homes for the handicapped. See City of Edmonds (LPC, p.9) 9 . 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Manufactured housing a. Manufactured home is term used in federal and state law for what used to be called a mobile home. Units must be built to construction standards set by federal government. b. Majority of courts have held that exclusion of "manufactured homes" or "mobile homes" from certain residential districts or allowance of such units only in parks is permissible. c. However, growing number of states have adopted legislation that prohibits complete exclusion of such units or that prohibits the discriminatory treatment of manufactured homes. d. Modular houses, built to standards for site-built houses, generally treated same as site-built homes for zoning purposes. Historic preservation a. Both historic districts and individual landmarks often subject to zoning. b. Establishment must be based on inventory of features and design guidelines based on unifying historic themes. c. Exterior alteration requires certificate of appropriateness d. Commission may be authorized to delay certificate for demolition for certain period of time to try to save building. See City of Boerne (p. 7) e. See "Historic Preservation" in Notes on Environmental Protection and Other Topics Signs and outdoor advertising a. Off-site commercial signs sometimes allowed in commercial and industrial districts, but complete prohibition has been upheld. See Metromedia (LPC, p. 19); Taxpayers for Vincent (LPC, p. 18) b. Federal legislation requires states to adopt control program for outdoor advertising displays along Interstate and certain federally aided highway. Regulations are generally weak. Federal law requires states to adopt legislation stipulating that "just compensation" must be paid if nonconforming outdoor advertising removed, thus banning amortization of these signs. c. Local ordinance standards may be more restrictive than state and federal standards, except with respect to just compensation requirement Sexually-oriented businesses (“SOBs") a. Includes adult theaters, adult bookstores, stores selling sexually-oriented paraphernalia, "topless" dancing clubs b. Contrast "dispersal" strategy with "combat zone" approach c. Most adult businesses implicate First Amendment right of expression, at least to marginal extent. Thus such uses may not be effectively prohibited. d. Separation requirements of up to 1,000 feet have been approved between one such business and another and between use and residences, churches, schools, and the like. Standards must be based on "secondary impacts" of such use rather than attempt to restrict activity itself. Such impacts must be documented by study although findings of study from another community may be transferred, if appropriate. See Young (LPC, p. 21); City of Renton (LPC, p.17) Wireless telecommunication facilities a. 1996 Federal Telecommunications Act limits zoning of telecommunication facilities (i.e., antennae and towers) used for cellular and personal telecommunication service (PCS) telecommunication. b. Local governments may not: i. Unreasonably discriminate among wireless providers that compete against one another ii. Prohibit or have the effect of prohibiting the provision of wireless service 10 iii. iv. v. IV. Fail to act within a reasonable time on permit requests Deny a permit request without basing it upon evidence included in a written record Deny a permit request on grounds that its radio frequency emissions would be environmentally harmful if the facility will meet emission standards set by the Federal Communications Commission. Legislative and Quasi-Judicial Decision-Making in Zoning A. Quasi-Judicial Decisions 1. B. Decisions that involve the application of the law to a particular party, that involve discretionary standards for decision-making, that require written findings of fact to justify the decision, and that typically allow third parties to intervene in a public hearing prior to the decision. Forms of Quasi-Judicial Relief 1. Special use permit (also known as the conditional use permit or special exception) a. May be granted by governing board, board of adjustment or planning b. Based on notion that certain types of uses are permissible in a zoning district, but only at certain locations and under certain locations. c. Approval criteria and standards for such permits must be spelled out in ordinance. d. The granting body must follow quasi-judicial procedures in hearing the permit application and in making its decision. e. Some approval criteria may apply to all uses for which such a permit may be issued (typically called "general" standards); other approval criteria may apply to particular uses for which a permit may be granted (generally called "specific" standards. Standards must be sufficiently definitive to guide administrative discretion. In some states standards need not be as definitive if legislative body grants permit. f. If the requirements for the granting of a special use permit as spelled out in the ordinance are met, the permit must be granted. g. Granting body may attach additional conditions to the permit that are not spelled out in the ordinance if these additional conditions are reasonable. h. Permission to develop land in accordance with a special use permit runs with the land and applies to future owners as well. 2. Variances a. Variance is a form of administrative relief from requirements of ordinance based upon "practical difficulties " or "unnecessary hardships” or both. b. Some courts consider terms “practical difficulties” and “unnecessary hardships” together to constitute a joint standard applicable to both use variances and area variances. Others, however, hold that a "practical difficulty" is required for an "area variance" whereas an "unnecessary hardship" is required for a "use variance." c. Most states allow variances based on unnecessary hardships. Although standards for such variances can be more demanding (see subpart (g) below) than for practical difficulties, some states authorize use variances based on unnecessary hardships. However, other states (including North Carolina) expressly prohibit use variances or effectively do so on the 11 d. e. f. grounds that they violate the spirit and intent of the ordinance or because they usurp the role of the legislative body. Generally granted by the board of adjustment or board of zoning appeals. Quasi-judicial hearing required. Courts have held that reasonable ad hoc conditions may be added to variance, even though zoning statutes typically do not mention that possibility. Required findings for the granting of a variance based on unnecessary hardship commonly include: i. If applicant complies with ordinance provisions, she can get no reasonable return from it or can make no reasonable use of it. ii. The property cannot be developed feasibly without a variance. (The hardship is suffered by the applicant's property. The applicant's personal, social, or economic circumstances are irrelevant.) iii. The hardship is not a result of the applicant's own actions. iv. Hardship is peculiar to the applicant's property and does not affect other properties in the same neighborhood. (If a number of properties suffer the same problem, the governing board may consider amending the zoning ordinance.) v. The variance is in harmony with the general purpose and intent of the ordinance and preserves its spirit. (No variance is lawful which authorizes precisely what a change in the zoning map would accomplish. 3. Other C. Legislative Decisions 1. D. Policy making decisions that establish law that may potentially apply to many members of the public that do not involve specific applications of the law to particular parties, and that do not constitutionally require any hearing to be held before they are made. Forms of Legislative Decisions: Zoning Amendments 1. 2. Spot zoning a. Spot zoning may be defined as an ordinance or amendment that singles out and reclassifies a relatively small tract owned by a single person and surrounded by a much larger area uniformly zoned, so as to impose upon the small tract greater restrictions than those imposed on the larger area, or so as to relieve the small tract from restrictions to which the rest of the area is subjected. b. Although the definition is often related to the geographic characteristics of the site, the key is whether the zoning is arbitrary and discriminatory and smacks of favoritism. c. "Spot zoning" actions are generally invalid unless there is some basis (e., planning policies) that would justify such actions. Floating zones a. Defined as a zoning technique under which the municipality adopts a zoning district in the text of the ordinance but does not map it except by petition of a property owner. The ordinance often specifies detailed standards for the approval of the floating zone. Because site plan may have 12 3. E. to be submitted to show that petitioner's proposal meets standards for mapping the district, use of floating zones is often a disguised way around doctrines against conditional or contract zoning. Contract zoning and conditional zoning a. Perceived need for contract zoning arises because most zoning districts allow a range of permitted uses. In applying a particular district designation to a property, neither the governing board nor the neighbors can know with any legal assurance which of the permitted uses may actually be developed. b. Contract zoning may be used to require the petitioner to restrict the use of his property to the use for which he seeks the amendment. The unit may also require the petitioner to abide by other protective conditions or impose various exactions. c. Two forms of this technique: contract zoning (sometimes called bilateral contract zoning) and conditional zoning (sometimes called unilateral contract zoning. d. Contract zoning often disapproved. In these cases either i. Unit and petitioner independently execute a contract, or ii. The rezoning ordinance state the terms of a bilateral agreement, or iii. The governing board relies unduly on the representations made by petitioner that development will be limited to certain specified uses. e. Contract zoning of this sort can be invalidated on grounds that legislative body may not contract away its legislative power to zone. f. Conditional zoning receives more of a mixed reception, but recently approved here in North Carolina. The restrictions are imposed unilaterally upon the petitioner. This approach avoids the problem of a legislative body binding itself in advance. Courts that uphold conditions on the property owner (landscaping, buffering, dedication or construction of improvements) generally emphasize the mitigation of the impact of the rezoning on neighboring properties. Some courts, however, invalidate the conditions or promises (not the rezoning itself) on grounds that such conditions violate the statutory requirement that regulations be uniform for each class or kind of building in each district (the so-called uniformity requirement). Exclusionary and Inclusionary Land Use Controls 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Definition: land use control regulations that have the purpose or effect of excluding activities from a jurisdiction in which they would otherwise locate L.U.L.U.'s: Land uses locally unwanted (in certain jurisdictions) include: a. low and moderate-income housing; b. group-care or family-care homes; c. half-way houses; d. billboards; e. adult entertainment establishments; f. manufactured housing and mobile home parks; g. hazardous waste facilities and landfills; h. junk and salvage yards. Some states have adopted legislation prohibiting local governments from excluding particular activities from the jurisdiction as a whole or from certain zoning districts. Courts in other states have developed doctrine that presumption of legal validity does not necessarily apply to regulations that exclude. Special justification is required. Exclusionary zoning in context of housing a. Definition: land use control regulations which singly or in concert tend to 13 b. c. d. e. exclude persons of low or moderate income from the regulating jurisdiction. Examples of techniques: i. exclusion by race ii. minimum lot size requirements iii. minimum floor area requirements iv. costly dedication, public improvement, and fee requirements v. exclusion of multi-family residential development vi. limitations on the number of bedrooms in dwelling units vii. exclusions of townhouses and other forms of single-family attached housing viii. exclusion of forms of manufactured housing Difficulty in attacking: Most zoning doctrine based on determining impact of zoning on a specific parcel of land or project rather than on impact upon entire community Legal bases for challenge: i. Equal Protection Clause of 14th Amendment to U.S. Constitution ii. Substantive due process (U.S. Const.) iii. Constitutional right to travel iv. Various state constitutional provisions v. Statutory purposes for which zoning or subdivision regs may be exercised State law i. Procedural issues Some states provide that if those challenging can show effect of zoning is exclusionary, the presumption that the ordinance is valid is lost, and the unit of government must assume burden of providing special jurisdiction. ii. Courts in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey have recognized special "builders' remedies." Exclusionary zoning not simply invalidated, but developer given site-specific permission to develop and/or court supervises amendment of ordinances to allow excluded housing to be built. iii. The "regional welfare concept" Early cases from Pennsylvania and Michigan focus on whether community has closed its doors to future growth. Evolved into notion that community has responsibility to consider "regional welfare." Cases invalidated large-lot zoning and exclusions of multi-family housing. iv. New York courts held that a municipality may prohibit multi-family housing only if regional and local housing needs supplied by the community or by other accessible areas within region. Two-part test: Has community adopted properly balanced and well-ordered plan? In enacting zoning has consideration been given to regional needs and requirements? v. California has codified the regional welfare concept into statutory law. vi. "Fair share" of low- and moderate-income housing (New Jersey style) aa. Mount Laurel I (LPC, p. 21) requires "developing" municipalities to provide reasonable opportunities for construction of community's "fair share" of low- and moderate14 income housing needed in region by removing barriers in land use regulations. Later cases held that communities have affirmative obligations to revise regulations and to eliminate undue cost-generating features such as subdivision ordinance exactions. bb. Mount Laurel II (LPC, p. 18) held that constitutional obligation extends not just to "developing" municipalities but to all municipalities classified as growth areas by the State Development Guide Plan. Communities must act affirmatively to make low-income housing available through subsidies to developers of low-cost housing, developer incentives, and mandatory set-asides of low-income units. vii. New Jersey Fair Housing Act (1985) aa. Exempts a municipality from "builders remedies" if it commits to adopt fair share housing plan. Sets up administrative appeal procedure to hear fair share challenges. bb. Allows "regional contribution agreements." One municipality may transfer its obligation to another by paying it to provide new units, rehab existing units, or replace substandard ones with new housing. f. Federal courts and legislation i. In Arlington Heights (LPC, p.20) U.S. Supreme Court held that exclusionary action did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of U.S. Const. Proof that a municipal zoning action had an adverse and disproportionate impact on blacks was insufficient; proof of a facially discriminatory intent or purpose was necessary to show a constitutional violation. ii. Supreme Court has held that taxpayers, a homebuilders' association, and several public interest groups interested in providing low-cost housing lacked "standing" to challenge an exclusionary ordinance. Court provided that in order to challenge exclusionary zoning practices, the plaintiff must allege "specific, concrete facts demonstrating that the challenged practices harm him and that he personally would benefit in a tangible way from the court's intervention." iii. Despite ruling in Arlington Heights above, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 may render some zoning actions invalid because of their racial impact, even absent a showing of discriminatory intent. iv. In a few cases plaintiff has charged that exclusionary zoning violates the constitutional right to travel. In federal district court decision in Petaluma that city's growth control plan was invalidated in part on grounds that this right was violated because the development regulations restricted right of persons residing outside city to migrate and settle there. On appeal, the federal court of appeals in Petaluma (LPC, p. 21) found that the developer lacked standing to raise issue and issue was not discussed. Also, in Belle Terre (LPC, p. 21) U.S. Supreme Court upheld restrictive definition of family despite claim that it infringed right to travel. 15 V. 6. Inclusionary Zoning and Housing a. Definition: using land-use controls to encourage or compel developers to develop housing for low-and moderate-income persons at below-market prices b. May be mandatory (e.g., compulsory "set-asides" of certain portion of housing units built) or optional c. May or may not involve density bonuses or other inducements. d. Often includes restrictions on resale or rents charged 7. Federal Fair Housing Act a. Makes it unlawful to make housing unavailable “because of race, color, religion, sex, familial status, . . . . national origin (or disability).” b. Act violation may be based on showing of discriminatory effect as well as discriminatory intent.” c. Cases based on racial or disability discrimination most common d. Discrimination against disabled expressly defined to include a refusal to make reasonable accommodations in rules necessary to afford disabled persons an equal opportunity to use a dwelling. i. Disability includes mentally ill, recovering addicts, and persons with AIDS ii. Requirements that subject group homes to special permit reuiqrements may violate FHA iii Special accommodation requirement may require zoning variance e. Discrimination on basis of familial status i. Adopted to stem tide of discrimination against familities with children ii. Act exempts bona-fide housing for seniors Controlling Residential Development A. Land subdivision control 1. Controls apply when land is subdivided for development and usually apply only to residential development. 2. Regulations do not control the use of land, but require compliance with design and improvement standards. May require minimum lot size requirements just as zoning. 3. Some states allow adopt of subdivision ordnance only after adoption of a comprehensive plan or a comprehensive plan and require consistency with it. 4. Ordinance generally prohibits the sale or recordation of lots before a recordable plat is reviewed and approved. 5. Process includes review of a. Sketch plan b. Preliminary or tentative plat c. Final plat 6. Preliminary plat includes all of the elements that ordinance requires for approval of final. 7. Right to subdivide may vest after preliminary plat approved 8. Subdivider generally authorized to begin construction of improvements after preliminary approved. 9. Ordinance may allow approval and recordation of final plat, subject to installation of improvements 10. Regulations may require performance guarantee or other assurance, approved with final plat, that improvements will be completed. Such guarantees and assurances include: 16 a. b. c. d. Letter of credit Bond Money or securities in escrow Requirement that improvements in prior stage of development are completed before final approval for subsequent stage given. e. Withholding of certificate of occupancy for buildings constructed in portions of subdivision for which improvements have not been completed. B. Developer exactions 1. 2. 3. 4. C. Compulsory dedication 1. 2. 3. D. Traditional approach has been to require developer to "dedicate" (offer to the public) sites, rights-of-way, and easements necessary for streets and utilities and related facilities that could be finance through special assessment on the benefited properties. Now majority of states authorize cities to require developers to dedicate sites for parks and recreational facilities, even though such facilities are not typically subject to special assessments and have been financed by community at large. A minority of states now allow cities to require the dedication of sites for other facilities (school sites, fire station sites, etc.). Construction or improvement requirements 1. 2. E. Definition: Any condition of development approval that requires a developer to provide or contribute to the financing of public facilities at its own expense. Growing trend to place more and more of the costs of providing the capital facilities required to serve new development on developers (and hence on new residents or owners of raw land) rather than having them financed by community at large. More common forms of exactions a. Compulsory dedication of land b. Construction or improvement of public facilities c. Payments in lieu of dedication or improvement d. Impact or development fees e. Land reservation requirements Legal requirements for exactions a. Ordinance or regulation must authorize them b. They must be authorized by statute or by provisions of a charter c. They must be in conformance with federal and state constitutional provisions (see below) Traditional approach has been to require developer to construct or install, or improve only those facilities (streets, water and sewer lines, drainage facilities, fire hydrants, street signs, etc.) that are needed "on-site" and benefit the properties being developed. Some jurisdictions now also require improvements to be made on the perimeter of the site that may benefit other properties (i.e., improvements to arterial streets abutting the development site or utility line extensions needed to reach the site). Payments-in-lieu 17 1. 2. 3. F. Impact or development fees 1. 2. 3. G. Similar in concept to fees-in-lieu, but not directly tied to "in-kind" requirements. They can be much more easily applied to facilities and improvements located outside the development as well as those on-site. Impact fees typically applied not only to subdivisions, but also to apartment, condominium, commercial, and even office and industrial developments that create the need for new off-site public facilities. Impact fees are typically paid at the time building permits are issued and must also be earmarked both as to purpose and planning district. Land reservation 1. 2. H. Payments-in-lieu systems have been developed in reaction to deficiencies of compulsory dedication and improvement requirements since one parcel of land or facility may serve an area larger than a single subdivision or development. Also, the task of improving a major street cannot easily be divided among developers who develop at different times. Payments-in-lieu payments made to the local unit in an amount representing roughly the value of the site or the improvement that would have been provided. Payments usually made prior to and as a condition of final plat approval and are placed in funds earmarked both by purpose (parks, school sites, etc.) and by planning area for which collected. Compulsory reservation useful where plans show that a site in a new development would be the most desirable location for new public facility, but local government cannot justify requiring developer to dedicate site. Reservation requirements require developer to abstain from subdividing or developing reserved property for a specific period of time. During that period, the agency for whom the site may negotiate to purchase the site or being eminent domain proceedings. If it fails to do so by the time the period expires, the reservation is lifted. The constitutional tests for evaluating exactions 1. 2. 3. Perhaps the most critical test that an exaction must meet is that it be constitutional; it must not deprive the developer of his property without due process and it must not constitute a "taking" without just compensation. Despite the fact that the compulsory dedication involves putting private property into public hands without payment by the unit, courts have uniformly upheld such dedications if it meets the following tests: The "specifically and uniquely attributable test: If the burden cast upon the developer is specifically and uniquely attributable to his activity, then the requirement is permissible. If not, it is forbidden and amounts to a confiscation of private property rather than a reasonable exercise of the police power. a. Most restrictive constitutional test. b. Benefits must inure almost exclusively to residents of development. c. Requirements for the dedication and improvement of interior streets, utilities, and similar local improvements meet test. d. Park or school site dedication requirements may meet test only if development rather large and isolated. e. Apparently prevents unit from imposing exaction if nearby public facilities are already in place. 18 4. The "reasonably related" test or "rational nexus" test: If the exaction is "reasonably related" or has a "rational nexus" to the nature and extent of the development proposed, the exaction is permissible. a. As a general rule, the benefits must not inure solely to the subdivision, but there must be some demonstrable benefit to it. b. Test provides that benefits to the development from the required exaction need not necessarily equal or exceed costs of the exaction, at least not when original need for facility is generated by the development. c. Exaction (particularly fees) may support facilities located off-site in appropriate circumstances. d. Under this test courts have been unwilling to tolerate exactions of land or money for facilities that the unit has no present plan for providing. The timing of the development and the needs it generates for new facilities and the actual availability of the new facilities for which the exaction was imposed must roughly coincide. e. Test, like specifically and uniquely attributable test, provides that exactions may not be imposed on developments already substantially served by public facilities, although some states would approve exaction if it could be shown that new development generally creates the need for the type of exaction sought to be imposed. 5. The constitutional test in Dolan (LPC, p. 10) a. Exactions must be "roughly proportional" to the impacts caused by the proposed development. b. Precise mathematical calculation is not required. c. Individualized determination must be made that the requirement is appropriate. d. Burden of proving the constitutionality of a development exaction is on the unit of government that imposes it. 6. See also Del Monte Dunes (LPC, p. 6) where court implies that Dolan test does not apply to exactions in the form of fees rather than real property VI. Growth Management A. Definition: government program intended to influence the rate, amount, type, location, and/or quality of future development within a jurisdiction B. Moratoria and Interim Controls 1. 2. 3. 4. A drastic restriction on development for a limited period of time designed to allow government to develop long-term solution to a problem or emergency May need to comply with certain ordinance adoption procedures Considerations a. Is it in response to an emergency or serious problem? b. Is it imposed for proper purpose? c. How long will restrictions remain in effect? d. What control does the community have over the problem that gives rise to moratoria? Moratorium of 32 months prohibiting virtually all significant development not an unconstitutional taking per se and did not amount to a categorical taking in Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. (LPC, p. 5) 19 C. Timing, Phasing, and Adequate Public Facilities Programs 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. D. Growth Control Quotas 1. 2. E. 2. 2. Query: may government refuse public service extension (particularly utility service) as a means of implementing growth management plan? If service is proprietary in nature, then is unit subject to a duty to serve similar to duty imposed on private utilities? Generally a utility may refuse to provide services only for utility-related reasons. Courts have provided mixed response to question of whether local government public enterprise has such a duty to all who want service. State Growth Management Program 1. 2. 3. VII. Basic concept: additional urban growth is allowed within the growth boundary but restricted or prohibited outside it. Provision of new services usually controlled by the designation of growth areas. Variant of concept involves a number of service areas or "tiers" as a means of directing growth. Controlling Growth through Public Facilities Extension 1. G. Program places a quota on growth, either absolutely or annually; growth typically allocated under criteria that may include point system. (See exercise in problem set III in these materials.) Growth control quota upheld in Construction Industry v. City of Petaluma (LPC, p. 21) Urban Growth Boundaries 1. F. Adequacy public facilities criterion: Linking development permission to the availability and the availability of public facilities to serve it Authorized in principle in Golden v. Town of Ramapo (LPC, p. 22) Generally must be accompanied by a good faith effort to increase the capacity of public facilities. New Hampshire legislation: authorizes APF program after adoption of a master plan and a capital improvement program Maryland legislation: prohibits certain local governments from issuing building permits unless water supply, sewerage system, and solid waste facilities adequate Florida legislation: local development regulations must provide that either public facilities are available when needed to serve development or development permits conditioned on the availability of services necessary to serve new development: “concurrency criterion” Smart growth initiatives have grown from state growth management systems. Programs often include four elements: a. Enactment of state legislation establishing program b. Preparation of comprehensive plans by local governments c. Review of local plans by a state agency d. Provision of state incentives and disincentives to encourage local compliance. See handout entitled “State Growth Management Programs.” Environmental Land Use Controls/Legislation 20 A. Introduction 1. 2. 3. 4. B. Environmental programs not well integrated with zoning and land use controls Planning slow to incorporate environmental values Environmental programs may require more drastic limitations on land use than zoning normally provides More potential for "regulatory taking" than traditional zoning Protecting Natural Resource Areas 1. 2. Wetlands a. Coastal or inland--salt or freshwater marshes, swamps, meadows, bogs, fens, pocossins b. Functions served: Natural areas valued for recreation, for education, reduce flood peaks, detain stormwater, recharge groundwater, support wetlanddependent fish and wildlife and food chain, filter water quality c. Federal Wetlands Protection Program of the Clean Water Act i. Sec. 404 requires permits for discharges of pollutants into the "waters of the United States (including wetlands) ii. Sec. 404 jurisdiction shared by EPA, and Army Corps of Engineers iii. Corps may issue permits for the discharge of dredged or fill material at specified disposal sites iv. EPA may veto a permit if discharge will have unacceptable adverse effect upon water supplies, fishing areas, wildlife, or recreational areas v. Corps may consider wide range of public and private impacts, including their cumulative effects vi. EPA prohibits permit if practical alternatives exist with less adverse impact on aquatic system. Practical alternatives presumed to exist if project not water-dependent vii. Mitigation: EPA requires applicants to "minimize potential adverse impacts" First, mitigate by not filling. Second, if impacts unavoidable, redesign. Third, if wetland loss occurs, mitigate through on-site or off-site restoration, creation, or purchase of wetlands. Mitigation banks created by developers allow creation or restoration so as to "bank" them for future projects viii. Is policy of no net loss feasible? d. Is prohibition on filling an unconstitutional taking? i. Just v. Marinette County (LPC, p. 22), upheld wetland regulation requiring preservation of wetland in its natural state, justified as preventing harm to the environment ii. Note Lucas (LPC, p. 13) rejects harm-benefit rule and implies that restricting land to undeveloped uses amounts to a taking Floodplains a. Natural flood overflow areas adjacent to stream channels. Includes area subject to 100-year flood (statistical chance that flood will occur is 1% in one year. Includes stream channel, its overbank area, and adjacent floodway fringe. b. Development typically prohibited in floodway. Structures allowed in floodway fringe, if elevated or floodproofed. c. Federal Flood Insurance Program i. Encourages private insurers to provide insurance for structures in floodplain. Participation by communities voluntary, but is a requirement for loans from private lenders regulated or insured by 21 feds or for receipt of direct federal financial assistance. Communities must adopt floodplain regulations to make property owners in community eligible for federally subsidized flood insurance. iii. Program administered by Federal Emergency Management Agency iv. Query: Has availability of program prevented flood loss? Or has availability of insurance encouraged development by providing an assurance that losses will be paid if flooding occur? d. Is a floodplain regulation a taking? i. Restriction on use of land to prevent flooding other's land may fall within nuisance exception to per se taking rule. ii. Unclear if regulation applies to land under development that is at risk. iii. Takings claims mitigated in flood fringe areas where certain forms of development generally allowed. ii. 3. Agricultural Land Preservation a. National Agricultural Land Study (1981) found crisis in conversion of agricultural land to urban uses and for water impoundment facilities b. Original concern: nation’s capacity to produce adequate supplies of food. More recent concern: loss of open, less developed areas, characterized by ag lands, beng converted into suburban sprawl. Hidden concern of farm community: preservation of farmers and farming way of life c. Incentives: i.. Do incentives prevent conversion of farmland, delay it, or only subsidize former farmers? ii.. Most states authorize preferential or deferred assessment of agricultural land at agricultural use value for property tax purposes (on urban fringe use value generally far less than market value for developed urban uses) . iii.. Agricultural districts: legally recognized geographic areas initiated by farmers and approved by a government agency. Landowners enter into binding agreements with agency for certain number of years to keep land in farming, triggerng certain limitations on governmental power aa. Limitations on use of eminent domain in such districts bb.. Limitations on use of special assessments to finance urban -type improvements in district cc. Special property tax treatment c. Right-to-farm laws i. May limit liability of existing farms from private nuisance suits as urban residents move into agroicultural areas (known as “comng to the nuisance”) ii. May limit applicability of local government nuisance actions d. Agricultural zoning i. County zoning statutes n some states exempt agricultural use. ii. Nonexclusive ag zoning: allows non-farm-development subject to large minimum-lot sizes, area-based allocation systems, conditional use permits iii.. Exclusive ag zoning: nonfarm uses and dwellings prohibited iv. Purchase of development rights (i.e., conservation easements) v. Agricultural land protection as part of growth management system (see Oregon system stating agricultural land be preserved and maintained for farm use. Also use of technique of urban growth boundaries and exclusive agricultural zones) e. Purchase of development rights (conservation easements) 22 i. Sometimes used in transfer of development rights program or in agricultural trust program ii. Landowner restricts right to develop land in ways incompatible with its use as farmland for the benefit of public agency or private ag lands preservation organizations iii. Most states have state-funded conservationon easement programs f. Federal response i. Environmental impact statements (EIS) required by Natonal Environmental Policy Act directs federal agencies to consider the loss of prime farmland ii. Farmland Protection Policy Act requires USDA to develop criteria for identifying effects of fdefal actons on farmland preservation 4. Environmental Impact Statements a. See "Environmental Impact Review" in Notes on Environmental Protection and Other Topics 5. Transfer of Development Rights a. Regulatory system in which the right to develop property can be separated or severed from land in a particular zoning district, sold or transferred to other property owners, and exercised in connection with the development of land in some other area of the jurisdiction (in a receiving district) b. See Penn Central (LPC, p. 20), Suitum (LPC, p. 8) c. Used for resource protection in Pinelands in New Jersey and in Montgomery County, Maryland d. Based on following methodology: i. Establish projected (or allowable) growth for area within planning period ii. Establish base allowable densities for various zoning districts and convert into allowable development rights iii. Determine providing districts and receiving districts iv. Property owners in restricted (downzoned) areas may sell development rights severed from the parcel for which they were established to owners of land in receiving districts e. Market for severed development rights may depend on creation of a development rights bank with ability to buy rights from restricted owners f. Problems: i. Difficult to create active market for development rights ii. Difficult to make work if ordinary rezonings easy to obtain in receiving districts iii. Use of development rights at receiver sites may result in significant differences in density between properties subject to normal density limitations and properties for which transferred development rights exercised 6. Coastal Setback Legislation a. National Coastal Zone Management Act provides funding for state coastal management programs. These include: i. State land development control applying to coastal properties ii. Wetlands and floodplain regulations programs iii. Beachfront management statutes b. Coastal setbacks designed to control erosion of beaches and dunes 23 Lucas held South Carolina’s beach setback law to be taking per se because it denied all economically viable use of the landowner’s property unless it could be defended under nuisance law. South Carolina Supreme Court later ruled that restriction could not have been imposed under law of nuisance, hence taking upheld. d. Subsequent to Lucas, court have held that a taking does not occur because of beach setback if owner acquired land after coastal law was adopted. 7. See Notes on Environmental Protection and Other Topics c. 24