OTHER COURSES TAUGHT - College of Liberal Arts

OTHER COURSES TAUGHT

HISTORY 151-(Fall 2002)

AMERICAN HISTORY TO 1877

Professor Michael A. Morrison Office Hours:

Office: University Hall 225 Monday:

10:00-11:00

& by appointment

Phone: 494/4804/494-4127 (work) 463-0087 (home) e-mail: mmorrison@sla.purdue.edu

(work) nfg-mam@att.net

(home)

Course Description:

This course explores American history from the beginning of European settlements to the end of the Reconstruction of the Union. It has three interrelated objectives. The first is to introduce some of the major themes, events, and personalities in the period so as to give the student a basic framework of the American past. Second, it attempts to develop the student’s ability to understand some of the interpretive problems historians encounter and debate in explaining the past. Third, our goal is to develop critical thinking and other related skills that students can deploy in other classes and in their own personal and professional lives. The format of the class is a mix of lectures in a large classroom setting and small discussion sections that encourage student participation.

“The only thing new in the world is the history you don’t know.”

Harry S. Truman

Required Reading:

Alan Brinkley, American History: A Survey, Volume I: to 1877 (11 th edition)

Primis, American History: A Document Collection

Michael A. Morrison, ed., The Human Tradition in Antebellum America

The assigned readings are available for purchase at Follett’s and University Bookstores.

The text ( American History ) and reader ( Human Tradition) will be made available on reserve in the undergraduate library.

Course Outline and Reading Assignments for lectures:

1. Discovery, Exploration and First Settlements

August 19-23

READ: Chapters 1 (entire) and 2 (pp. 34-40) in American History,

Primis, pp. 1-9

2. Errand into the Wilderness: The Puritan Experience

August 26-30

READ: Chapter 2 (pp. 40-49) in American History

Primis, pp. 11-14, 16

3. The Growth of Colonial British North America

September 4-6

READ: Chapter 2 (pp. 49-63) and Chapter 3 (entire) in American History

Primis , pp. 24-25

4. The Founding of a Nation: The American Revolution, 1763-1783

September 9-20

READ: Chapter 4 (entire) and Chapter 5 (pp. 126-129) in American History

Primis , pp. 30-45

5. We the People: The Origins of the American Constitution

September 23-27

READ: Chapter 5 (pp. 147-156) and Chapter 6 (pp.160-167) in American

History

Primis , pp. 46-60

6. Securing the Revolution: The Early Years of the American Republic

September 30-October 4

READ: Chapter 6 (pp. 167-178) and Chapter 7 (entire) in American History

Chapter 1 in Human Tradition

MIDTERM EXAM: Thursday evening, October 10, 7-9 p.m. in Matthews (MTHW) 210

7. The Age of Jackson, 1824-1844

October 14-18

READ: Chapter 9 (entire) and Chapter 10 (entire) in American History

Primis, pp. 61-66

Chapters 4 and 5, 8 and 9 in Human Tradition

9. The Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1844-1854

October 21-November 2

READ: Chapter 13 (pp. 344-361) in American History

Primis , 67-70

Chapters 11 and 13 in Human Tradition

10. A House Divided: Sectionalism, Secession, and Civil War

November 4-December 6

READ: Chapter 11 (entire) and Chapter 13 (pp. 361-368) in American History

Primis , 71-74, 78-84

Chapters 10 and 14 in Human Tradition

ATTENDANCE:

I will not take attendance at the lectures. You are responsible for all of the material covered in lectures, however, and you will find it difficult in the extreme to pass this course without regular attendance. I will not make my lecture notes available.

EXAMS:

There are two in-class exams for this class: a midterm and a final. The midterm is scheduled for Wednesday evening, October 10, from 7-9 p.m. in Matthews (MTHW)

210. I have scheduled it for the evening so as to relieve students from the pressure of time or “clock-watching.” The exam will not take two hours, but I want to give students the luxury of taking their time without having to worry about the clock. The second exam will take place during finals week. The time and place will be announced. I will also schedule two other alternate dates so that you can fit the final into your very busy schedule that week. It will cover the material in lectures and discussions from the midterm to the end of the semester. It is not cumulative .

Each exam will contain five identification terms and one essay question. To help you prepare for the tests, you will receive a list of identification terms and essay question options. The essay question on each exam will come word-for-word from that study sheet. To help you prepare for the midterm exam , there will be an in-class review session on the Wednesday (October 9) before the midterm; discussion sections will be cancelled that week. For the final exam, the discussion sections in the week that precedes the final exam will be wholly devoted to a review and preparation.

DISCUSSION SECTIONS:

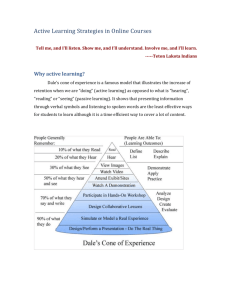

In addition to the Monday and Wednesday lectures, each student will attend one discussion session per week. These discussion section meetings replace a third lecture, so the workload for this class is the same as for any three-credit hour class. At the most basic, these discussions are mean to provide students with an alternative to the large lecture class where learning is passive. The purpose of the discussion session is to provide students with an intimate learning environment that will allow them to participate actively in their own education. These weekly meetings will first review lecture material then focus on the assigned readings. They will allow students to ask questions, pursue matters not covered in lectures, debate with one another, seek clarification of lecture

material, and, in general, pursue the issues covered in the course in a small-class surrounding in which they are active participants.

Each student will write a total of ten (10) informal papers based on the readings for discussion section in weeks chosen by the student . That is, there are twelve assigned readings for this fifteen week semester. (The first and the last weeks of the semester have no assigned readings for discussion sections, and discussion sections will be cancelled for the week of the midterm exam.) Students must write a total of

10 papers during the semester; each paper will be 1 1/2 to 2 pages in length.

Students are free to choose which weeks they will not write a paper. In the weeks that the student does not write a paper, s/he is still obliged to do the reading, attend section, and participate in the discussion of the group. The writing assignments are described below. The papers will be graded and worth a maximum of 10 points a piece.

Thus you can receive a maximum of 100 points for these one- to two-page papers.

The point of these papers—or homework assignments, if you will—is to a) ensure that the students do the assigned reading; b) reward them for doing the work; and c) to take an edge off of the weight of the midterm and final by allowing students to build up their grade gradually over the semester. The larger purpose of the weekly meetings, however, is to allow students an active participation in their own education. Thus the discussion section meeting will spend some time reviewing the material in class; but the bulk of the hour will be focused on discussion and debate. The level of participation is up to each student.

ATTENDANCE POLICY FOR DISCUSSION SECTIONS

Although I do not take attendance for lectures, I do expect that students will attend the discussion sections especially during the weeks that they hand in their writing assignments . To meet the spirit of this expectation, if a student hands in a writing assignment before or after the discussion section— and does not attend the discussion section itself

—s/he will receive no higher than five (5) points—out of ten (10)—for the writing assignment. This is only fair to those who play by the rules and meet the expectations of the discussion section part of History 151.

EXTRA CREDIT

Although students are required to hand in only ten (10) written assignments, they may hand in up all twelve (12) assignments. We will count the highest ten (10) scores and drop the lowest two (2).

TEACHING ASSISTANTS:

Two of the greatest learning resources in this class are the teaching assistants.

The teaching assistants assigned to this class are Mark Lewellen-Biddle and Jay Hopler.

Both Mark and Jay have had a great deal of experience working with undergraduates, and they are outstanding a members of our graduate program. Most important, Mark and Jay are here to help students do the very best that they can in History 151. Make use of their many, many talents.

Mark Lewellen-Biddle Jay Hopler

REC 420 REC 406

Ph: 49 67475 Ph: 49-61702

Email: marklewellen_biddle@hotmail.com Email: jhop605@aol.com

GRADING:

Believing both in the Protestant work ethic and laissez-faire market principles, there will be no curving in this class. Nor will there be any predetermined number of As,

Bs, Cs, Ds, and Fs. Each student will be rewarded for her or his efforts, nor will anyone be penalized for working hard and playing by the rules. Each student controls her or his destiny (grade-wise, that is) in this class.

Mid-term exam: 100 points

Final exam: 100 points

Weekly class writing assignments: 100 points

The final grade will be determined thusly:

A: 300-270

B: 269-240

C: 239-210

D: 209-180

F: 179-“Look out Below!”

“Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.”

H.G. Wells

WEEKLY WRITING ASSIGNMENTS

FOR DISCUSSION SECTIONS

Week of August 26 : You are a newly arrived and somewhat lonely settler in Virginia and have relatives back in England who are thinking about joining you in the New

World. You miss them and would like to have their good company, but you also have come to know well how different life is in Virginia, especially having witnessed Bacon’s

Rebellion. Write a two to three-page letter to your loved ones describing life as you have come to know it in the colony. You may assume that your letter will greatly influence their decision whether to stay in England or make the trek to the New World.

(Material: lecture, Primis , pages 1-9, American History , pages 34-40)

Week of September 2 : If you are a male, assume that you are an attorney and write a two-page defense of Anne Hutchinson. If you are female, you are the prosecutor in the trial and write a two-page indictment of her. In either instance, base your arguments on the material in the text and reader and ground your case on the culture of Puritan New

England.

(Material: lectures, Primis , pages 11-14, 16, American History , pages 42-47)

Week of September 9 : You are a white indentured servant and, not surprisingly, you are really cheesed off at the arrogant, self-important, exploitative white ruling establishment in Virginia. Being mad as hell, you are not going to take it any more. You need allies in your political struggle against that upper-class elite, however. Write a short political broadside (or appeal) addressed to African-American slaves that will be distributed throughout the colony to drum up support for your cause. Be sure to point out to them the similarity of your conditions and circumstances so that they will see the justness of and enroll in your cause.

(Material: lectures, Primis , pages 24-25, American History , pages 66-67, 71-75)

Week of September 16 : God help us all, assume you are a young, aspiring lawyer and the assistant to the chief prosecuting attorney in Boston. Your boss is thinking about bringing charges against various British officials and officers for their involvement in the

Boston Massacre and the slaughter of innocent colonists at Lexington. Write a memo

encouraging or discouraging him from bringing charges basing your judgment on the conflicting accounts of both events found in Primis. Remember if you are wrong in your advice, you’re out of a job with the city and will have to chase ambulances for the rest of your sorry career.

(Material: lectures, Primis , pages 34-39 , American History , pages 114-115, 121-122)

Week of September 23 : Assume that you have the heavy if unhappy responsibility to be

King George III's political advisor. The colonists have sent along documents in Chapter

3 Primis including the Resolution For Independence, an excerpt from Paine's Common

Sense , and a copy of the Declaration of Independence found in the text, American

History . Your responsibility is to draft a two to three-page rebuttal to the general points made in those documents. King George will incorporate your arguments into a speech to

Parliament in which he will declare his thirteen colonies in revolt and call on the House of Commons and House of Lords to support a military effort to put down the rebellion. If he fails because your rebuttal is not persuasive, you will find yourself chained up in the

Tower of London among the rats, waiting to be broken on the rack and trying in vain to make your peace with your God.

(Material: lectures, Primis , 39-45, American History , pages 126-127, Appendix, A9-10)

Week of September 30 : Assume that you are an Antifederalist campaigning for the ratification convention in your state. You have read the new Constitution and listened to all of the bogus arguments made for it by antidemocratic spokesmen such as James

Madison in his Federalist Number 10. Write a one- to two-page political broadside detailing your objections to this new government. Remember the success of your candidacy depends on the persuasiveness of your case.

(Material: lectures, Primis , pages 46-50, American History , pages 166-167)

Week of October 14 : You are an up and coming young man (yes even the women in the class) with your eye on the main chance (that is, you want to get rich!!!). Your father wants you to take the safe sober route of Hiram Hill. You, being a bit of a roustabout, think that John Smith’s life, fame and riches are the way to go. Before you head to the frontier, write a short letter to dad explaining why you chose not to become an upstanding

(and wealthy) member of the community like Hill and, instead, are going to try your luck in Ohio.

(Material: Human Tradition , chapters 4 and 5, American History , pages 188-194,

218-221)

Week of October 21 : You are a southern governor who wants to get reelected say in

1836. Write a letter to your land-hungry, white constituents supporting Indian removal .

The persuasiveness of your argument to dispossess the Choctaws or Cherokees from their homeland will go a long way to ensuring the success of your candidacy. Remember there are whites and Native Americans who strongly oppose removal, and you will have to rebut their arguments effectively or it’s back to the cotton fields with you.

(Material: Primis , pages 61-66, Human Tradition , chapters 8 and 9, American History , pages 244-248)

Week of October 28 : The rise of Jacksonian democracy and the Democratic Party is widely hailed as the “Age of the Common Man.” Perhaps. Assume that you are either

Laura Wirt Randall or Peggy Eaton (men and women in the class) and you are on your deathbed. Write a short letter to your children (who will read it once you’ve gone to your final reward, have joined the “choir invisible,” and are now taking an eternity-long “dirt nap”) reflecting on your life as a woman in this age of equality .

(Material: Human Tradition , chapters 11 and 13, Primis , pages 67-70, American History , pages 324-325, 333-334)

Week of November 4 : Assume that you are, Col. Horatio Beauregard, a bourbonguzzling, slaveholding candidate for the United States House of Representatives. The slavery extension question has all of the voters in your district in a tizzy. Draft an outline of a speech defending the South’s (and southerners’) right to take their slaves into the commonly owned territories of the West. Remember this is no easy task a) since you are a slaveholder most of your constituents think that at best you are an arrogant jackass and at worst perhaps the antichrist; and b) they don’t own any slaves, they don’t intend to own any slaves and so why should they care a hoot about this issue. Persuade them—I dare you.

(Material: lectures, Primis , pages 71-74, 78-79, American History , pages 355-359)

Week of November 11

If your name begins with A through L:

Write a description of life in the North from any point of view below:

A southern plantation owner

A slave

A poor white Southerner who doesn’t own slaves

If your name begins with M through Z:

Write a description of life in the South from any point of view below:

A social worker

A factory worker

An antislavery politician

(Material: lectures, Human Tradition, chapter 14, American History , pages 302-306,

361-363)

Week of November 18 : Two weeks ago you were concerned with defending slavery within the American political system and, by extension, preserving the Union of all the states. This week you are a flaming abolitionist who does not give a hoot in hell whether the Union survives or not—slavery must go. Having just read Hosea Easton’s Treatise, you are now convinced that slavery is a crime against humanity. Write a short letter to your local antislavery newspaper promoting Easton’s work, arguing that his analysis is correct, and urging the paper’s readers to go out and buy it. Remember that the editor

(i.e., the teaching assistant) does not like long, rambling letters and that you only have a couple of pages of paper to make your case: make it a short, emotional appeal.

(Material: lectures, Human Tradition , chapter 10, Primis , pages 80-84,

American History, pages 334-341)

Week of December 2 : Review for the final exam.

HISTORY 385 (Fall 2000)

AMERICAN POLITICAL HISTORY

Professor Michael A. Morrison Office Hours:

Office: University Hall 308 Monday & Wednesday, 2:00-3:00 p.m.

Phone: 494-4804/494-4122 (work) and by appointment

463-0087 (home) e-mail: mmorrison@sla.purdue.edu

(work) nfg-mam@.att.net

(home)

Books Available for Purchase

The following paperback books are available for purchase at Follett's and University

Bookstore.

Jack N. Rakove, James Madison and the Creation of the Republic

Harry L. Watson, Andrew Jackson vs. Henry Clay: Democracy and Development in

Antebellum America

William E. Cain, ed., William Lloyd Garrison and the Fight Against Slavery: Selections from the Liberator

Ellen Fitzpatrick, ed., Muckraking: Three Landmark Articles

Bruce J. Schulman, Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism

Course Outline and Reading Assignments

Foundations and Parameters

August 21-September 8

Read for Discussion on September 8: Rakove, Madison, pp. 1-79

Origins of American Political Parties

September 11-22

Read for short essay quiz and discussion on September 15:

Rakove, Madison, pp. 80-104

Read for discussion on September 22:

Rakove, Madison, pp. 105-48

Journal pick up in class, September 11

Second Party System

September 25-October 2

Read for short essay quiz and discussion on October 2:

Watson, Jackson vs. Clay, Part 1

Disruption of the Second Party System

October 4-18

Read for short essay quiz and discussion on October 18:

Cain, Garrison, Part 1

Journal pick up in class, October 13

Gilded Age Politics: From Stalemate to Crisis

October 20-23

From the Square Deal to the New Deal: Reform Politics, 1900-1937

October 25-November 20

Read for essay quiz and discussion on November 3:

Fitzpatrick, Muckraking, Part 2: “The Documents”

Journal pick up in class, November 10

The Politics of Pluralism

November 27-December 8

Read for essay quiz and discussion on December 1:

Schulman, Johnson, chapters 3-6

Journal pick up in class, December 4

Grading:

1. Essays and Discussions

I have come to two sad conclusions after these many years in the trenches. First, long term papers in survey-level courses generally are too burdensome on the student and, alas, unsatisfactory to the professor. Second, discussion sessions without an “incentive” to do the reading are too burdensome on the student and, alas, unsatisfactory to the professor. Therefore I have scheduled five quiz/discussion sections for the semester; the dates are: September 15, October 2, October 18, November 3, and December 1 .

We will discuss the assigned readings for thirty minutes, and then the class will take a quiz over that material. First, I want to give the students a number of opportunities to accumulate points toward their final grade. Second, since we will be discussing the material that will be covered in the quiz, it will be an “incentive” to do the reading.

Thirdly, students are sometimes reluctant to participate in discussions, even though they

have done the reading. They should benefit from having done the work: the quiz will give them something for their efforts. Each quiz will be worth a total of 20 points.

2. Journals

Each student will keep a journal that will reflect on the lectures, discussions, readings, and videos. These are to be considered informal writing exercises. For example you might choose to summarize lectures, to explain why a reading is difficult to understand, to disagree with a point made by me or someone else in class, to raise questions, to make connections between different topics or themes of the class, to express excitement at seeing new ideas, or for any other purpose. These journals are to be treated like a diary or a “learning log,” which allow you to write about the course in a number of ways.

Students will write a minimum of three pages per week . You should keep these entries in the same spiral bound notebook so that they remain all together. I will pick the journals up four times during the semester: September 11, October 13, November 10, and December 4.

Each grading of the journal will be worth a maximum of 25 points.

3. Final Exam:

There will be a take-home final exam . The exam will be distributed the last day of class

(December 8), and it will be due no later than the following Friday, December 15, at 5:00 p.m. It will consist of three question options, and the student will select and answer two.

The questions (and therefore your answers) will draw on the lecture material and assigned readings. Each question will be worth a total of 50 points for an overall total of

100.

Course grades will be distributed thusly:

Quizzes: 5 @ 20 points= 100 points

Journals: 4 @ 25 points each=100 points

Final Exam: 100 points

To determine your final grade add the totals and divide by 3. You will end up somewhere between 0 (gasp) and 100 ( yes!

). The final grade will be based on a straight scale basis.

HISTORY 495M (Fall 1999)

RESEARCH SEMINAR IN HISTORICAL TOPICS:

SECTIONALISM AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

Professor Michael A. Morrison Office Hours:

308 University Hall Monday & Wednesday, 1:00-2:00 p.m.

494-4804/4122 (work) & by appointment

463-0087 (home) e-mail: morrisom@purdue.edu

(work) e-mail: nfg-mam@worldnet.att.net

(home)

Course Description:

This course is intended for undergraduate history majors and other students interested in the historian’s craft. Its purpose is to provide students with a greater understanding of the political, social, cultural, and intellectual issues pertaining to the growth of sectionalism in the United States in the 1850s and, subsequently, the human experience of the American Civil War. The class is a mixture of lectures, class discussions based on the readings, interpretation and discussion of visual presentations

(videos), exams, and a semester-long research paper based on primary sources.

Books available for purchase:

Richard H. Sewell, A House Divided: Sectionalism and Civil War, 1848-1865

Harriet A. Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself

George Fitzhugh, Cannibals All! or, Slaves Without Masters, ed. C. Vann Woodward

Robert W. Johannsen, ed., The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

Glenn M. Linden and Thomas J. Pressly, Voices from the House Divided: The United

States Civil War as Personal Experience

Course Outline:

Week 1 (August 23-27): Introduction, library resources and tour

Week 2 (August 30-September 3): The Sectional Issue Introduced into Politics

READ: Sewell, A House Divided , Chapter 1

Weeks 3-5 (September 8-24): North of Slavery—The Institution and its critics

READ: Sewell, A House Divided, Chapter 2

Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

Weeks 6-8 (September 27-October 15): Liberty and Slavery: Southern Politics and

Society

READ: Fitzhugh, Cannibals All!

Weeks 9-11 (October 18-November 5): And the War Came

READ: Sewell, A House Divided, Chapters 3 and 4

Johannsen, ed., The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

Weeks 12-14 (November 8-22): Ordeal by Fire: The American Civil War as a Human

Experience

READ: Sewell, A House Divided , Chapters 6 and 7

Linden and Pressly, Voices from the House Divided

Weeks 15-16 (November 29-December 10): Paper presentations and sober second thoughts

Assignments:

A variety of writing assignments are due throughout the semester. The core of this class, however, is a 12-15 page term paper that will be based on primary sources. I am appending a list of possible topics (Appendix B), all of which bear generally on the material covered in the class and the readings. Each student will select a specific topic from that list or of her or his own choosing (and with my approval). S/he will then compile an extensive bibliography of not less than thirty

(30) entries—a combination of primary (documents, letters, newspapers, congressional debates, etc.) and secondary sources (books and articles written by historians on the topic). Students will also hand in a three to four page essay based on outside readings on the chosen topic with a one-sentence thesis statement of the final paper; an abstract (100-200 words) that summarizes the argument of the larger paper; a first draft of the paper to be reviewed by me and one of your peers in the class; and a final version of the paper to be handed in the last week of class. The process for writing the paper will be described in

Appendix A.

Class Participation:

At each discussion section (five in all) students will take a ten-minute quiz on the lectures and assigned readings; each will be worth 10 points. The quiz will take the form of an short (two-page), exploratory writing assignment such as a thought letter or a legal brief based on a particular issue that has been stressed in the readings and lectures. For example, I might ask you to imagine that you are an abolitionist. I would then ask you to write a letter to an editor making a plea for the immediate abolition of slavery. Or, alternatively, I would ask you to assume that you are a South Carolina fire-eater; your task would be to write a short, political broadside arguing for immediate secession.

Following the quiz, there will be a discussion of the materials covered in class and in the assigned readings. Students will receive between 1-10 points, depending on their level of participation in discussion. One point is awarded for attending class and staying awake (if you nod off, then you receive nothing—and the rest of the class will sneak out and leave you snoring away). Ten points will be awarded for enthusiastic participation.

Teaching Assistant:

I am fortunate in the extreme to have one of the most talented and advanced graduate students in the department’s doctoral program as my teaching assistant.

Ms. Susanna Calkins is well on her way to finishing what promises to be a firstrate dissertation on the public and private lives of Quaker women. Susanna has audited my undergraduate class in American history, and she has taught her own survey level class in European history. More to the point, Ms. Calkins is very familiar with writing research papers and the sources of the SLA library. She will be available to students to work with them in a tutorial fashion as they research and write their papers. Rather than limit herself to fixed office hours, Ms. Calkins will be available to students at a time and place that are convenient to both.

Grading:

Quizzes—5 @ 10 points maximum: 50 points

Discussions—5 @ 10 points maximum: 50 points

Bibliography: 25 points

Essay on proposed topic: 50 points

Peer Evaluation: 25 points

Final Paper: 100 points

Final Grade Calculation:

A range: 300-270 points

B range: 269-240 points

C range: 239-210 points

D range: 209-180 points

F(ailing): 179 and (look out) below

APPENDIX A

PAPER-WRITING GUIDE FOR HISTORY 495M

Task: The purpose of this course is twofold: first, to familiarize the student with the causes and consequences of sectional politics and the American Civil War; second, to introduce students to the historian’s craft. That is, the course is meant to both discuss and think about a particular historical topic and to instruct students in the art of research and writing history. Since, however, only a small portion of the class—if any—will do postgraduate work in history (these would be the insane), this class has a larger purpose. I hope to give students skills—researching, note-taking, critical thinking, and essay writing—that they can deploy and employ in other classes and in their own professional and personal lives. To that end, each student will choose a theme on a personally selected topic and write a 12-15 page paper based largely on primary-source research. After reading, digesting, and analyzing the primary-source materials that relate to your topic, each student will write an essay that assesses carefully how this issue contributed to the coming of the American Civil War or reveals the human dimension of that conflict.

Audience: Since I already am (or allege to be) an expert on the American Civil War, please assume that I know all of the answers to, and opinions on, your essay option.

Therefore, students will assume for the time being that they are historians (ugh! Gag me with a spoon!) and are using their research findings to inform their colleagues in this class how the war came about or how it affected the millions touched by it. Put in other terms, I want each student to situate her/his work in the context of the 1850s and 1860s to explain to the average undergraduate (if such a person exists) how this particular issue reveals one of the many causes or consequences of the sectional conflict between the free and slave states. (Though your classmates are your audience, anyone using “like” as an all-purpose verb will automatically fail the course.)

Format: The paper should be no less than twelve pages and no more than fifteen pages, exclusive of endnotes. It must be typed, double-spaced, and properly footnoted (here see the Chicago Manual of Style ). The essay must begin with a thesis that addresses the proposed topic option, and is supported by evidence drawn primarily—though not exclusively—from the primary sources that you have examined. Please use spell check and grammar check before handing in the draft and final versions: it will save you embarrassment and me migraines.

Expectations: Students should conceive of this writing assignment as a semesterlong process (here do not insert “ordeal” for “process”). This will be a very different approach than the slap-dash, frenetically written, end-of-semester paper that has proven historically to be a disappointment to the author (you) and the reader (me).

The first step will be to select a topic. This will be done by the second week of class.

On the Friday of the fourth week of class, students will hand in their bibliographies.

On the Friday of the seventh week of class, students will hand in a four-page essay on the topic with a thesis statement for the larger paper. On the tenth week of class, students will provide an abstract of 100-200 words that summarizes your argument; this will not be graded but is a course requirement. Failure to turn in the abstract will mean a penalty of one-half of your final grade. On the twelfth week of class students will provide two copies of the first version (or draft) of the paper. One will be given to a peer (classmate) for review; I will critique the other. Although peer reviewers or

(reviews) will be graded on the thoughtfulness of their contribution to this collaborative effort, no grade will be given to the first draft. Monday and

Wednesday of week thirteen will be devoted to peer review; students will receive my comments on the first version of the paper on Friday of that week. The final version of the paper will be due on the last day of class.

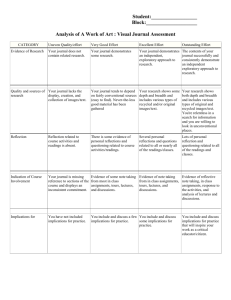

Criteria for Evaluation: After the short essay on the topic (week seven) has been returned, students will receive a guide to the criteria by which the final paper is to be graded. It will weigh different features according to importance (e.g., thesis statement, evidence, argumentation, historicism (is this topic analyzed on its own terms?), grammar, etc.). Each student and peer will evaluate her/his first draft on the basis of this analytical framework, as will I. The final product will be evaluated on the same basis. Though the particulars—and the rating form—will come later, the emphasis is, on the whole, on your ability to think about and analyze materials like a historian. This means being more concerned with cause and effect (“how” and “why” things happen) than a narrative of “what” happened. As one of my esteemed colleagues has put it, the goal of this paper assignment (and the class generally) is to understand that history is not a given (there is no book-o-history that contains “the truth”). Rather it is an ever evolving product of a dialogue between the past (as it emerges from your primary sources) and the present (your inquiring mind and analytical ability).

APPENDIX B

LIST OF POSSIBLE PAPER TOPICS

1.

Debate on the Annexation of Texas, 1844 (Democrat or Whig, abolitionists) a) election of 1844

2.

Debate on the Mexican War, 1846-1848 (Democrat or Whig)

3.

Debate on restricting slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico as a consequence of the war, 1847-1848.

a) election of 1848

4.

Debate on the compromise measures of 1850 a) arguments on the impact of slavery on the South b) arguments in favor of slavery c) arguments for congressional noninterference

5.

Assessment of compromise measures, 1850-52 a) election of 1852

6.

Debate on the Kansas Nebraska Act (Democrats for; Democrats and free-soilers against,

Southerners for and against)

7.

Debates on the civil war in Kansas, 1854-57

8.

Dred Scott decision, 1857 (Democrats [North and South], Republicans) a) Lecompton Constitution

9.

Lincoln-Douglas Debates

10.

Religion and slavery (for it against it)

11.

Abolitionism

12.

Women and abolitionism

13.

The institution of slavery (from the African-American perspective)

14.

Slave revolts

15.

Election of 1856 and Know-Nothing party

16.

Territorial Expansion: Ostend Manifesto (1854); Filibustering; 1849-51 (López & Cuba),

1855-56 (Walker & Central America)

17.

John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry

18.

Election of 1860 (take any one of the four parties: Union Democrats (north); Constitutional

Democrats (South); Constitutional Unionists (conservatives); Republicans

19.

Efforts to Compromise (Peace Convention, February 1861; Committee of 13 report in

Congress, 1861)

20.

Southern secession debates—generally or by state

21.

Northern reaction to secession—Democrats or Republicans

22.

Fort Sumter, April 1861

23.

The personal effect of war on soldiers, wives, parents, etc.

24.

Military operations of the war