ARTIFICIAL REEFS

Marine and Freshwater

Applications

Edited by Frank M. D’Itri

LEWIS PUBLISHERS, INC.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Main entry under title:

Artificial reefs.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Artificial reefs United States

2. Artificial reefs—Japan. I. D’Itri, Frank M.

SH157.85.A7A78 1985

551.4’24

85-213

ISBN O-87371-OlO-X

—

COPYRIGHT © 1985 by LEWIS PUBLISHERS, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Neither this book nor any part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording,

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from

the publisher.

LEWIS PUBLISHERS, INC.

121 South Main Street, Chelsea, Michigan 48118

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

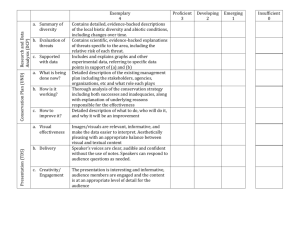

CHAPTER 13

UTILIZATION OF ARTIFICIAL REEFS IN THE

INSHORE AREAS OF LAKE MICHIGAN

Fred P. Binkowski

Center for Great Lakes Studies

University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee

Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53201

INTRODUCTION

Twenty—five to thirty years ago, recreational fishing in Lake Michigan along the shore of

Milwaukee County was excellent. The most abundant and important fish caught during that time

was the yellow perch, Perca flavescens. Sport fishermen were able to fill their live nets with

jumbo perch ranging in size from 23 to 140 cm. It wasn’t uncommon for fishermen to catch 50 to

100 perch in 2 or 3 hr. Some of the prime fishing areas during this time were off the breakwater

wall at South Shore Park, the north/south government pier and the Jones Island wall. From

mid—June through August most of these areas were occupied by hundreds of people fishing

from the piers and breakwater walls, and an equal number fishing from boats anchored off these

structures.

By the late 1950s other areas, such as the Lakeside Power Plant, McKinley breakwater wall,

Sheridan and Grant Park jetties, and the Oak Creek Power Plant became recognized as prime

perch fishing areas. In addition, the yellow perch was also an important component of the

commercial catch in Lake Michigan for many years with some of the best inshore, commercial

fishing occurring off of Wind Point, just south of the Milwaukee County line. This shoreline area

has been identified as a traditional perch spawning ground (Coberly and Horrall, 1980). In the

early 1960s the commercial harvest reached a peak of 2.6 million kg in Lake Michigan. By 1970

the commercial catch declined by more than 80 percent (Smith, 1970). The rapid decline of the

yellow perch population in Lake Michigan could be attributed to the introduction of the alewife

(Smith, 1968, 1970), the decline in water quality and the destruction of spawning habitats and

nursery grounds, with the latter being the most significant. The perch sport fishery which attracted

many fishermen to the harbors, piers, and shallow waters of Lake Michigan each summer also declined.

In Wisconsin waters of Lake Michigan this declining pattern continued until the mid—

1970s when the yellow perch population began to gradually increase. In 1977 the commercial

harvest doubled and there have been some good signs that the perch population will continue to

increase, albeit, slowly.

Several studies are now being conducted on the relationship between substrate type and

spawning, hatching, and the survival and growth of yellow perch in Lake Michigan by biologists

at the University of Michigan.

At the present time, the best yellow perch sport fishing in Wisconsin waters of Lake

Michigan bordering Milwaukee County is occurring in rocky or rip—rap areas off the Lakeside

Power Plant, Oak Creek Power Plant, and along the breakwater wall of South Shore Park with

the heaviest fishing pressure occurring off the South Shore Park shoreline and breakwater wall.

Based on 1981 gill net ‘survey data, the perch population at South Shore Park showed an

increase concurrent with the construction of an artificial reef in Lake Michigan at South Shore

Park (Figure 1). There was also a significant increase in the species diversity of the reef area.

Figure 1. Artist’s sketch of the South Shore Park Marina and primary perch

In July, 1980, Milwaukee County spent approximately $6000 for a dredging project along the

lakefront at South Shore Park. About 283 m3 of silt and sand were removed from this area. In

November, 1980, the Milwaukee County Park Commission spent another $4000 to construct an

artificial reef made up of 68 metric tons of beach stone and 77 metric tons of field stone. The

rock piles are approximately 4.56 m wide and 1.52 m high. The edge of the reef is about 2.13 m

from the fishing wall (Figure 1).

In 1981, the Center for Great Lakes Studies, University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee received a

$4000 research grant from Milwaukee County to investigate the possibility of restoring the

yellow perch habitat at South Shore Park. The South Shore Park reef was considered to be an

ideal site to investigate the utilization of a shore zone artificial reef by forage and sport fishes

and compare the sport fishing success at the reef site with other popular and historical inshore

fishing areas.

The first reported artificial reefs were constructed in the early 1800s (Edmond, 1960; Elliott,

19146). Studies have shown that large numbers of fish will congregate near or on artificial reefs.

This is usually due to an increase in the biological productivity of the reef area (Popenoe, 1978).

Reefs may also serve as spawning and nursery grounds for young fishes (Prince et al., 1975).

The concept of artificial reefs has been used more extensively in marine environments and has

proven to be very successful in concentrating fish and increasing the number of fish caught per

angler hour (Turner et al., 1969; Walton, 1976, 1979; Stone et al., 1979). Freshwater reefs have

also been utilized for the same purpose as in the marine environment but to a lesser extent.

Investigators from Michigan State University sponsored by the Michigan Sea Grant College

Program are evaluating the biological and economical feasibility of a large limestone reef in 7.6

to 15.2 m of water (see Chapter 16). This type of reef can be utilized by offshore boat fishing

only.

The South Shore Park reef is unique, in that it is located in 3.04 to 3.65 m of water and less than

2.0 m from shore. This type of reef will serve the shoreline fishery. The primary objectives of

this investigation were to: (1). determine the effectiveness of this reef in increasing biological

productivity and attracting fish, thus increasing angling opportunities and (2) identify an area in

the shore zone of Lake Michigan which historically provided good fishing success and construct

an artificial reef in this area and measure its potential to congregate both forage and sport fishes.

There are approximately 32 or more kilometers of Lake Michigan shoreline along southern

Milwaukee County (similar.to the South Shore Park site) with public access that have the

potential for development into prime shoreline recreational fishing areas to serve the urban

community.

The development of urban fishing areas has been advocated in recent years by city governments

and other agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service,

American. Planning Association (formerly ASP.0), Water and Power Resources-Service, Urban

Wildlife Research Center, Inc., and Sport Fishing Institute. Interviews conducted with groups of

sport fishermen revealed an urgent need to develop the shore fishery at South Shore Park, the

north/south breakwater wall, the McKinley breakwater wall and the St. Francis Power Plant.

One. of the most typical statements made by people during these interviews was that senior

citizens, -young children and people who are not able to operate or own boats can’t get to the

good fishing spots. In order for these people to participate in the sport fishery they would have to

fish fran shore.

The intent is that these shallow water reefs will help in developing an urban recreational fishery

for perch and other sport fishes for people who are limited to shoreline fishing.

APPROACH

Following a dredging operation in July 1980, the construction of the reef at South Shore Park

was completed in November 1980. The reef bed, encompassing an area of approximately 11400

m2, was covered with a combination of sand and pebble sized beach stone. The super structure

of the reef was constructed of football sized field stone. The reef was divided into three separate

sections consisting of two designs. One design was a pier—like structure about 14.5 m long, 2.14

in wide and 1.5 in high, with a crescent at the distal end from shore. The second design was a

boomerang shape. Both of these designs maximized the refuge area of the reef, especially during

storm conditions from a southeasterly direction (Figure 2A).

Periodic inspection of the reef was done in conjunction with the stocking of sac-fry in 1981 and

the collection of rocks to quantify the extent of reef colonization by invertebrates (Table 1). In

May 1981, six months after its construction, the reef’s layout had changed (Figure 2B). The

design was more box shaped, with the boomerang reef still intact. By 1983 there

Table 1. Qualitative Invertebrate Survey: South Shore Park Artificial Reef

Organisms identified:

Isopoda Cirolanides

Annelida Hirudinea (leeches)

Annelida Oligochaeta

Turbellaria Trichladida Planariidae

Gastropoda

Hydr’acarina Hydrachnae Hydrachnae (water mites)

Cladocera Daphnidae Daphnia

Coelenteratea Hydroida Hydra americana

Botatoria Trichoceridae (rotifers)

Diptera Chironomidae (larvae and pupae)

Ostracoda Podocopa

Amphi poda Gammaroidea Gainmari dae Gamrnarus

Trichoptera Hydroptilidae (caddis fly larvae)

Porifera Spongilladae

Pelecypoda Sphaeriidae (freshwater clam)

Copepoda Cyclopoida Cyclopidae

Protozoa Plasmodrorna Ciliata

was a significant change in the reef layout compared to the proposed design in 1980. The ends of

the reef including the boomerang are now connected, resembling the letter M or an inverted W

(Figure 2C).

In the spring of 1981 we collected spawning adult perch from Green Bay. This work was done in

cooperation with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Besources (WDNE). The eggs were

removed from the females and fertilized in the field. The fertilized egg ribbons were transported

back to Milwaukee where they were incubated in the laboratory to the sac—fry stage. In May,

1981, we stocked approximately 200,000 sac—fry on the reef. Sampling to measure larval fish

density and early survival on the reef was conducted using a 0.5 meter 360 micron mesh

plankton net equipped with a flowmeter gauge. No perch larvae were found in the plankton net

samples.

From May through September, 1981 and June through August, 1982 one experimental gill net 76

m long was set overnight on the reef once a week, and 2 to 3 graded mesh gill nets 76 m long

were set in other locations within the South Shore Park area. This additional gill netting was part

of a harbor survey

Table 2. Incidental catch species list for South Shore Reef gill netting.

Size range

Species

Number

1981

Yellow Perch, Perca flavescerns

White Sucker, Catostomus cornmersoni

Rainbow Trout, Salmo gairdneri

Alewife, Alosa pseudoharengus

Northern Pike, Esox lucius

Green Sunfish, Lepomls cyanellus

Sculpin, Cottus spp.

Black Bullhead, Ictalurus rnelas

Spottail Shiner, Notropis hudsonius

Coho Salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch

Brown Trout, Salmo trutta

(mm)

426

18

12

100 - 300

300 - 450

195 - 348

1982

Yellow Perch

Alewife

Sucker

Rainbow Trout

Trout Perch, Percopsis omiscocnaycus

Northern Pike

Brown Trout

project conducted by the WDNR, to determine the abundance of the pre—spawniflg, spawning,

and post—spawning perch population. The experimental gill net mesh size ranged from 0.3 cm2

to 3.8 cm2. The graded mesh gill size ranged from 2.2 cm2 to 14>~ cm2 The experimental and

graded mesh gill net sets were the primary source of infcmation to evaluate the utilization of the

reef by both forage and sport fishes.

When representatives from the Milwaukee County Government requested our help with the

design and construction of this reef the primary objective was to enhance the sport fishing within

this unique shoreline area. This habitat improvement concept prompted us to consult with the

WDNR on the design, construction and location of the reef. The decision was

Table 3. Size distribution of South Shore Park yellow perch.

(99

2 July 81

9July81

16 July 81

22July81

29July81

8

89

Size (trim)

100—1149 150—199 200~2149 250—299

—

12

1

2

5

21

6

8

11

3

9

—

—

20

10.

22

5

2

300+

12

7

114

9

1

1

—

5 Aug 81

12Aug81

19Aug81

26 Aug 81

3 Sept 81

10 Sept 81

16 Sept 81

214Sept8l

2Oct81

2June82

16June82

7 July 82

15 July 82

28July82

11 Aug 82

—

3

13

13

1

2

1

19

20

21

9

3

3

3

—

—

—

9

—

1

2

1

2

1

12

8

6

1

—

3

-

—

—

1

—

—

1

—

—

-

8

10

11

13

6

15

9

5

14

—

—

—

1

1

—

—

1

1~4

—

10

8

13

—

2

-

1

1

—

—

-

14

2

2

1

—

—

1

2

—

-

unanimous: the South Shore Park area would provide the best site to test the success of the reef as a

device to congregate fish, which in turn would increase angling opportunities.

In interviews with sport fishermen prior to the construction of the reef, it was noted that the most

abundant sport fish in the area was the rainbow trout with some incidental catches of yellow perch usually

about 150 mm in length. Many of these fishermen spent long hours fishing and all they had to show for

their effort was an empty live net at the end of the day.

During the summer of 1981 and 1982, gill net sampling was conducted once a week on the reef

and beach seine hauls were made in the South Shore Park area with a 7.6 m bag seine. At the same time

the reef survey was being conducted the WDNT~ was collecting information on the abundance of yellow

perch in other locations near the reef area using graded mesh gill nets. These sampling locations consisted

of mostly a sand bottom with some submergent vegetation and a minimal amount of rock out-

ARTIFICIAL BEEFS IN INSHORE AREAS OF LAKE MICHIGAN

357

croppings. The two most abundant species collected were yellow perch and white suckers. The perch caught in these nets ranged

in size from 180 to 300 plus mm. On several occasions fish as large as 330 mm were caught with the average size between 230

and 250 mm. The species diversity number was significantly lower as canpared to the fish collected on the reef. A total of twelve

species was collected on the reef: 5 forage and 7 sport species for 1981—82 (Table 2).

Two stomach analyses studies were conducted on South Shore Park yellow perch to determine selective and/or seasonal

feeding patterns. The first occurred between July 2 and October 2, 1981 with 426 fish collected and

the second from June 2 to August 11, 1982 with 143 fish collected.

Perch ranged in size from 65 to 303 mm. The majority were females. In 1981 the population was dominated by larger

(150 to 299 mm) fish throughout July and early August, but became almost exclusively yearlings

(100 to 149 mm) from mid—August to October. The 1982 study revealed a population consistently

dominated by fish ranging between 100 and 199 mm fish (Table 3).

Perch larger than 160 mm generally consumed only other fish (Table 14). Of the identifiable fish remains, sculpin, 9— spine

stickleback and alewife were common prey. In 1981, perch consumed almost exclusively large

alewives (40 to 100mm) during July, but all three species in August. In the 1982 study, sculpin and

stickleback were the most consumed species, with sculpin being more favored in early to mid—June and

stickleback from mid—June to August. Few alewife were consumed. One interesting note: in the 1981 study it

was common to find 2 or more fish per stomach, while in 1982 there was rarely more than one.

In both studies it appeared that the perch smaller than 160 mm consumed a wide variety of foods including chironomid larvae

and pupae, amphipods, isopods, hydracarina, culicids, leeches, snails, crayfish, and eggs of other fish. In 1981

and 1982, the large amounts of eggs consumed in July disappeared by August. Also in August sharp increases

occurred in the volume of foods consumed as well •as more selectiveness of isopods as food objects. In late

August and September chironomid larvae and amphipods also became a significant portion of the perch diet.

Prior to the reef construction we were not aware of any significant increase in the numbers of different sport fishes congregating near~ the reef

area. Following the construction of the reef both the abundance and size of yellow perch collected in the reef area increased significantly. Also

for the first

358ARTIFICIAL REEFS

Table 4. Frequency of occurrence of various food items in yellow perch less than and greater than 150 mm

Yellow

Perch

Vertebrates

Fish

Fish

Eggs

PM

AMP

Crustaceans

ISO

HYR

DEC

1981

< 150 mm

14

17

12

30

64

6

1

(244 fish)

>

150 mm

(194 fish)

1.6

2

6.9

126

14.9

10

12.3

2

26.2

6

2.5

14

1.0

614.9

5.2

1.0

3.1

2.1

7

1982

27

10

40.9

15.2

0.4

0

0

<

150 mm

(66 fish)

0

3

0

150 mm

(77 fish)

0

14.5

29

10.6

>

7

5

16

2

2

0

37.7

9.1

6.5

20.8

2.6

2.6

21

31.8

0

0

PM = Plant Material; hydracarina; DEC = decapoda.

KEY:

AMP = Amphipoda; ISO isopoda; HYR

359

ARTIFICIAL REEFS IN INSHORE KREAS OF LAKE MICHIGAN

Table 14 (continued). Frequency of occurrence of various food items in yellow perch less than and greater than 150 mm

Insects

Annelids

CR1

GUI.

TBI

ODO

HYM

OLI

RIB

GAS

UNID

EMP

89

36.5

25

10.2

3

1.2

14

1.6

0

0

3

1.2

0

0

1981

0

0

22

9.0

68

27.9

12

6.2

1

0.5

0

0

1

0.5

0

0

1

0.5

0

0

33

0

50.0

15

19.5

0

0

0

1

1.5

1

1.3

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

1.3

0

0

1

1.3

0

0

1

1.3

0

0

10

5.2

38

19.6

1982

3

3

14.5

0

0

14.5

0

0

18

27.3

22

28.6

KEY:

CR1 chir-onomidae; GUI. = culicidae; Thl trichoptera; ODO = odonata; HIM hymenoptera; OLI = oligochaeta; HIR hirudinea; GAS =

gastropcda; UNID unidentifiable; E~~P = empty

360

ARTIFICIAL REEFS

time northern pike were collected in our gill nets, something unheard of in the past.

Due to money constraints the sampling program on the reef was minimal in effort. Even with the low sample size we feel

that the reef was responsible for attracting a large number of different species, and even more

important was the congregating of some sport species which previously were rarely seen in the area.

One unusual situation that still puzzles us is the fact that there were many large perch congregating on the reef and

the fishermen would work their baits in the right area, but only a few large fish were caught off the reef. Most of the

larger fish continued to be caught off the breakwater.

The function of the reef has definitely served its purpose in that it has begun to congregate forage fish which attract

sport fish which in turn attract anglers. At present, the concept of inshore reefs has carried over into the electric

power industry. There is some interest in developing inshore reefs using fly ash blocks to enhance and rehabilitate

both sport and commercial fish populations, and provide a cost effective approach to utilizing these fishery

resources.

SUMMARY

The concept of using artificial structures (reefs) in freshwater systems, specifically Lake Michigan, has received little attention.

The use of rocks, anchored logs and brush piles has commonly been used in inland lakes as substrate for increasing the biological

productivity, and attracting fish and increasing angling opportunities.

The primary objectives of this research were to identify an area in the shore zone of Lake Michigan which historically provided

good fishing success, design and construct a reef within this area, and measure its potential to increase biological production and

congregate both forage and sport fishes. The reef was constructed of field stone and was located in 3 to 3.6 in of water within a

breakwater area. Observations were made of the reef using SCUBA in 1981, 1982, and 1983 to determine the effects of wave

action and ice on its shape and dimensions.

In the spring of 1981 we began an experimental gill net survey which continued through October. Gill net surveys were also

conducted from June, 1982 through August, 1982. In 1981 approximately 200,000 yellow perch sac-fry were planted on the

ARTIFICIAL REEFS IN INSHORE AREAS OF LAKE MICHIGAN 361

reef. The gill net samples from 1981—82 were used to determine the species diversity on the reef as compared to the area

surrounding the reef. Sub—samples of fish from the gill nets were used for food studies. Fish samples from other locations within

the reef area were collected with graded mesh gill net and beach seines.

The majority of invertebrates colonizing the reef included numerous zooplankton, planarians, amphipods, leeches, and insect

larvae with isopods (Asellus) being the most abundant invertebrate.

The reef provided the highest fish species diversity as compared to other sampling locations within the reef area. Twelve different

species of fish were collected on the reef which included 5 forage and 7 sport species.

LITERATURE CITED

Coberly, C.E. and R.M. Horrall. 1980. Fish Spawning Grounds in Wisconsin Waters of the Great Lakes. University of Wisconsin

Sea Grant Publication (WISG 80—235). University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706.

Edmond, L. 1960. Marine habitat improvement in Japan. Foreign

Service Dispatch No. 180, American Embassy, Tokyo. U.S.

Department of State, Washington, DC. ~4 pp.

Elliott, W. 19~46. Carolina Sports ~ Land and Water. Burges and James Printers, Charleston, SC. 172 pp.

Popenoe, H.L. 1978. Artificial Reefs in Florida. Florida Sea

Grant College Report No. 224. University of Florida, Gainesville

FL 32611. pp. 1—3.

Prince, E.G., R.F. Raleigh, and R.V. Corning. 1975. Artificial

reefs and Centrarchid Bass. In: R.H. Stroud and H. Clepper

(eds.), Black Bass Biology and Management, Sport Fishing

Institute, Washington, DC 20005. pp. 2498~505.

Smith, S.H. 1968. Species succession and fishery exploitation in the Great Lakes. J. Fish. Res. Rd. Canada 25:667—693.

Scith, S.H. 1970. Species interactions of the alewife in the Great Lakes. Trans. Amer. Fish. Soc. 99:754—765.

Stone, P.?., H.L. Pratt, P.O. Parker, Jr., and G.E. Davis. 1979. A comparison of fish populations on an artificial reef in the Florida Keys.

NOAA/NMFS. Mar. Fish. Rev. 241(9):1—11.