Biography of Jurgen Habermas

advertisement

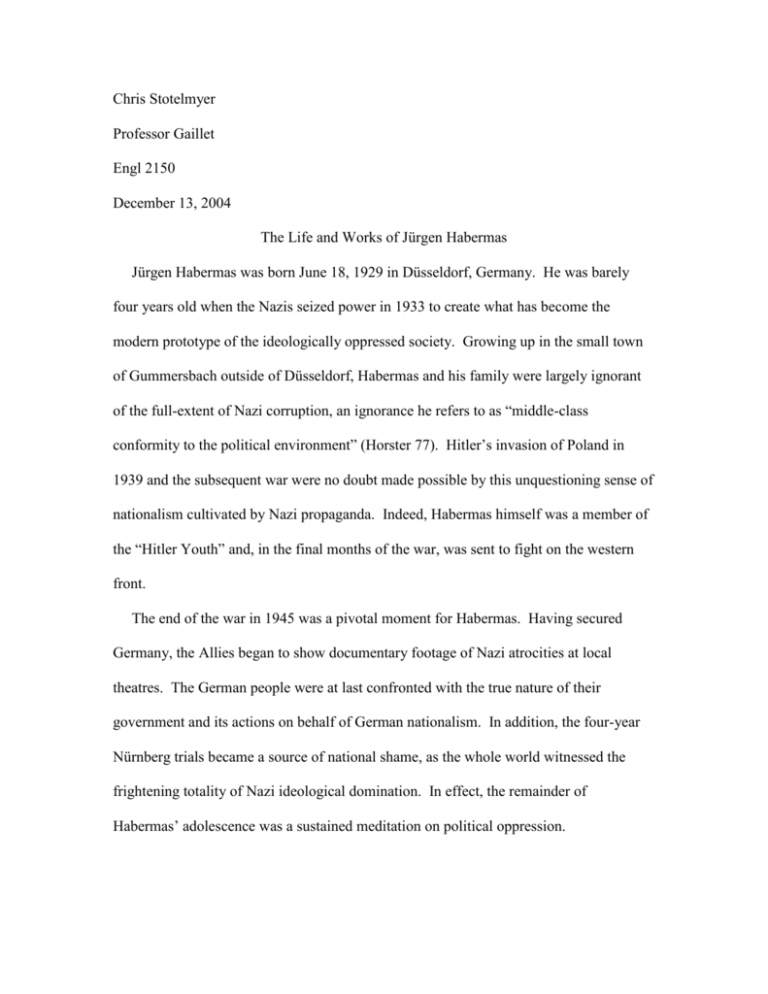

Chris Stotelmyer Professor Gaillet Engl 2150 December 13, 2004 The Life and Works of Jürgen Habermas Jürgen Habermas was born June 18, 1929 in Düsseldorf, Germany. He was barely four years old when the Nazis seized power in 1933 to create what has become the modern prototype of the ideologically oppressed society. Growing up in the small town of Gummersbach outside of Düsseldorf, Habermas and his family were largely ignorant of the full-extent of Nazi corruption, an ignorance he refers to as “middle-class conformity to the political environment” (Horster 77). Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939 and the subsequent war were no doubt made possible by this unquestioning sense of nationalism cultivated by Nazi propaganda. Indeed, Habermas himself was a member of the “Hitler Youth” and, in the final months of the war, was sent to fight on the western front. The end of the war in 1945 was a pivotal moment for Habermas. Having secured Germany, the Allies began to show documentary footage of Nazi atrocities at local theatres. The German people were at last confronted with the true nature of their government and its actions on behalf of German nationalism. In addition, the four-year Nürnberg trials became a source of national shame, as the whole world witnessed the frightening totality of Nazi ideological domination. In effect, the remainder of Habermas’ adolescence was a sustained meditation on political oppression. Stotelmyer 2 Many Germans had great hopes for the model of democracy brought to West Germany by the Americans and the British. Habermas, in particular, came to view the Allied victory not as a defeat but as a “liberation from a criminal tyranny”(Horster 4). His enthusiasm, however, was not boundless. During Germany’s economic reconstruction, Habermas began to experience a sense of disillusionment at what he perceived to be regressive political actions. Many important civil posts were filled with former Nazi sympathizers, creating a sense of tacit continuity of the previous regime. Habermas had begun his study of philosophy in 1949 at Göttingen University when these appointments took place. That year he attended the election meetings for the first Göttingen parliament. Habermas describes the experience: The party convention was decorated with black, white, and red flags and was closed with the German national anthem. I fled absolutely full of emotion; I simply could not stand it. (Horster 79) He saw in this experience the potential for a state to use a democratic model as a façade, or mask, of legitimacy. Despite these setbacks, Habermas remained optimistic for Germany’s future and, fortunately, Germany did escape the bonds of its past. In 1954, Habermas completed his graduate dissertation on F.W.J. Schelling and received his doctorate in philosophy in Bonn. His early postdoctoral years were critical in his emerging philosophy in that he began to study Marxist thought more closely. A reading of Georg Lukacs’ History of Class Consciousness inspired Habermas to consider whether a systematic argument could be made of Marxist thought. Lukacs’ work, however, was a critique, not a systematic approach to Marx. His ideas, therefore, did not lend themselves to a broad argumentative theory. Stotelmyer 3 Habermas eventually found appropriate theoretical framework for his thought in the writings of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer. Leaders of the so-called Frankfurt School of philosophical thought, Adorno and Horkheimer sought to develop a critical theory of society based on multiple fields of study. The work of the Frankfurt School philosophers was thus informed by psychology, sociology, anthropology, philosophy, and other disciplines. Habermas was particularly struck by Adorno and Horkheimer’s book Dialectic of Enlightenment, in which they applied Marx in a systematic way to help establish a social theory. Their ideas galvanized Habermas and for the first time his philosophical thought began to inform his political ideas. He began to apply the theories of the Frankfurt School to his own philosophy and, in 1956, was awarded an assistantship at The Frankfurt Institute for Social Research. The Institute for Social Research was home to the philosophers of the Frankfurt School in the 1930’s. Because of their decidedly left-wing sympathies, its members were exiled from Nazi Germany during World War II but continued their work at Columbia University in the United States. Eventually, the Frankfurt School theorists retired or passed on and it was left to Habermas, then, to carry their work forward in his own philosophy. In 1962, Habermas left Frankfurt to study in Marburg and published his seminal work The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, in which he critiques the political system of Germany. Habermas envisions the “public sphere” as a kind of institution that can monitor government, or power, through public discourse. He theorized the existence of many public spheres, all engaged in discourse with one another. His goal is to transform the public sphere into an entity that participates in discourse firmly grounded in Stotelmyer 4 rationality. Transformation established Habermas as a champion of Enlightenment principles in a rapidly evolving postmodern world. His next book, Theory and Practice, was published in 1963 and establishes two fundamental ideas. Habermas proposes two kinds of social actions. First, he defines “instrumental action” as action that “is governed by technical rules based on empirical knowledge” (McCarthy 391). In other words, this kind of action achieves specific goals under specific circumstances and, as such, is purposeful. Instrumental action is material and decidedly Marxist. Habermas calls his second type of action “communicative action.” Communicative action is simply communication or human linguistic interaction, particularly interaction that produces agreement or understanding. Habermas rejects the Marxist view that all human action is merely instrumental (i.e. production) and creates his second social model to account for moral or political motivations. Habermas feels that human beings lack freedom in modern society and his criticism of Marxism springs from the fact that Marx fails to address the human element in society. The idea that humanity is just a small part of an evolving economic machine is insufficient for Habermas. In 1964 Habermas returns to Frankfurt to accept a professorship at the University of Frankfurt, and for the next seven years publishes critiques of the major movements in social theory. It is this constant evaluation of the dominant social discourse (much of it postmodern) that solidifies his own philosophical ideas. Due to conflicts with the student protest movement, Habermas left Frankfurt in 1971 to head the prestigious Max Planck Institute. His disagreements with the protest movement demonstrate Habermas’s commitment to rationality. Although he supported the movement in general, Habermas Stotelmyer 5 was struck by what he saw as left-wing fascism because the students had become just as dogmatic in their beliefs as the conservatives they were opposing. This staunch advocacy of rational discourse came to fruition in 1981 with the publication of his groundbreaking work The Theory of Communicative Action. In its two volumes, Habermas puts forth a theoretical social apparatus with four main themes: the concept of the rationality of actions; an appropriate theory of action; a concept of social order; and the diagnosis of contemporary society (Robins 3). His theory is based on the concept of an ideal speech situation and the presence of validity claims. Validity claims are simply statements that are asserted as being true or valid. If, in the arena of everyday discourse, a validity claim is called into question, then participants must move to the arena of rational discourse. Put very simply, rational discourse must meet four conditions: 1. All participants are free to question and/or introduce assertions. 2. Participants have a right to represent their own views without external interference. 3. Participants are allowed and encouraged to express their attitudes, desires, and needs. (State any prejudices that may affect discourse) 4. Speech cannot be one sided. Rules applying to one participant apply to all participants. The goal of rational discourse is to examine validity claims in an effort to attain intersubjectivity. Intersubjectivity occurs when participants have reached an agreement and are able to work together, progress, and live peacefully. All participants will Stotelmyer 6 eventually be “on the same page” so to speak. By positing an ideal situation, Habermas believes society’s ills can be addressed. Shortly after the publication of Communicative Action, Habermas returned to the University of Frankfurt to resume his professorship. He would spend the next several years lecturing and refining his philosophy. In 1985, Habermas published The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, in which he attempts to defend modernity from the criticisms of the postmodernists. Habermas is perhaps the last philosopher to completely espouse and defend the ideals of rationality and human achievement advocated by Enlightenment philosophers. He is frequently called into debates to defend modernity with such postmodern thinkers as Lyotard, Gadamer, and Foucault. Postmodern thinkers have criticized Habermas’ strong affinity with Enlightenment rationality and, in particular, his reliance on the “universalist” view of ethics proposed by Kant. Kant held “that if there is something we can call morality, it cannot be private, but rather necessarily carries with it a universal and necessary command to all rational individuals’ (White 271). In other words, what is moral for one is moral for all. This universal view of morality is anathema to the postmodern assertion that all truth is relative. The modernist belief in human rationality and the existence of “Truth” are primary targets of postmodern criticism. Despite the criticisms of postmodernists, Habermas continues to be a powerful voice of rationality in a turbulent world. It is also important to remember that Habermas is equally critical of postmodernism, which he views as simply another form of irrationality. The breadth of his knowledge is enormous and his arguments can be devastating to his Stotelmyer 7 opponents. Because of his Enlightenment loyalties, Habermas’ is a strong believer in dialectic and open philosophical discourse. Over the past two decades, Habermas has lectured, debated, and published countless papers, and he has received several academic awards and accolades. Most recently he received the 2004 Kyoto Prize for Arts and Philosophy given by The Inamori Foundation of Japan. At 75, Habermas is still an active participant in public discourse, including the discourse surrounding the American occupation of Iraq. In an interview with Eduardo Mendieta in 2003, for instance, Habermas comments on the Bush administration’s behavior after September 11: The militarization of life domestically and abroad, the bellicose policies which open themselves up to infection by their opponents own methods, […] all this the politically enlightened American populace would have overwhelmingly rejected, if the administration had not, with force, shameless propaganda, and manipulated insecurity, exploited the shock of September 11. (Habermas “Interview” 9) In spite of America’s current problems, Habermas still believes now, as he did in 1946, in the American democratic ideal. Always optimistic, he recalls his thoughts in the autumn of 2002 concerning the American mindset: This was not ‘my’ America. From my 16th year onward, my political thinking, thanks to the sensible re-education policy of the Occupation, has been nourished by the American ideals of the late 18th century. (Habermas “Interview” 9) Stotelmyer 8 As an example of the Enlightenment belief in human achievement and progress, Habermas has no equal. Habermas lives in Munich, Germany. Stotelmyer 9 Works Consulted Habermas, Jürgen. Interview with Eduardo Mendieta. Logos Online. 11 Oct. 2004. 11 Dec. 2004. <http://www.logosjournal.com/habermas_america.htm>. Habermas, Jürgen. Theory of Communicative Action. 2 Vols. Boston: Beacon P. 1984. Horster, Detlef. Habermas: An Introduction. Trans. Heidi Thompson. Philadelphia: Pennbridge. 1992. Jürgen Habermas Web Resource. Ed. Steve Robinson. 1997. English 980: Studies in Rhetoric, Michigan State. 11 Dec. 2004 <http://www.msu.edu/user/robins11/Habermas/main.html>. McCarthy, Thomas. The Critical Theory of Jürgen Habermas. Cambridge: MIT P. 1978. White, Stephen K. Ed. The Cambridge Companion to Habermas. New York: Cambridge UP. 1995.