APA Project: Adjudication Section ___ HEARINGS: Some Issues

advertisement

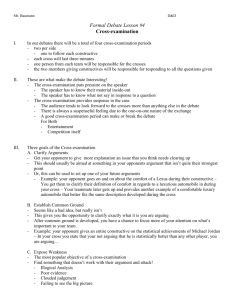

APA Project: Adjudication Section ___ HEARINGS: Some Issues Worthy of Consideration for Recommendations Steven Croley The following is a non-exhaustive list of topics relating to formal adjudication that may be worthy of consideration for reform recommendations: 1. Burden of Proof/Greenwich Collieries: Greenwich Collieriess determination that burden of proof in the APA refers to the burden of persuasion rather than merely the burden of production surprised a lot of courts and commentators. There wasissubstantial case law inconsistent with that holding. Is the decision a welcome one? For one thing, as Justice Souter points out in dissent, how is it compatible with the observation that when more than one party is seeking a particular result, like in a licensing for example, each party bears the burden? More than one party cannot bear the risk of nonpersuasion, can it? Second, what impact does GC have on the notion that a party may bear a burden on some particular issue, but not another? Does GC imply that now the party bears the burden of persuasion on that particular issue? In some cases, that might make sense, where for example the party is offering some kind of affirmative defense. On the other hand, where an agency has shifted the burden to a party with better access to information, considering that shifted burden one of persuasion rather than production might not make sense. Third, and more generally, is the GC approach a desirable one on the merits? On could make a strong argument that the burden-of-persuasion issue really is a policy question appropriately left to agency discretion. Davis and Pierce collected examples (pre GC) of how different agencies under different statutes allocate the burden differently (sometimes by statute but sometimes not). Why a blanket default rule, as GC contemplates instead? 2. Standard of Proof: Two issues relating to the standard of proof in formal adjudication suggest themselves for possible reform recommendations. The first concerns the relationship between the preponderance of the evidence standard, on the one hand, and language in APA section 556(d) describing the type of evidence (reliable, probative, and substantial) that shall guide the issuance of an order. In Steadman v. SEC, the Supreme 1 Court read 556's language to refer largely to the quantity rather than the quality of evidence. To what extent, then, are there quality controls on the evidence upon which an agency can rely? Undoubtedly so, but what exactly are those controls? Moreover, exactly how is it to be determined when an agency has satisfied the preponderance standard? Is the preponderance standard, given the nebulousness concerning the quality of evidence upon which an agency may rely, susceptible to general formulation? Or will courts recognize its violation only when they see it, in the context of a particular case? Second, what exactly is the interplay between the preponderance of the evidence standard of proof in adjudications, on the one hand, and substantial evidence standard of judicial review, on the other hand? Doesnt courts interpretation of substantial evidence undermine the preponderance standard, given that an agency can survive judicial challenge under the substantial evidence test without needing to demonstrate that a preponderance of the evidence in the record supports what the agency has done? Put differently, what is to stop an agency from issuing an order supported by substantial, but not a preponderance, of the evidence in the record? 3. Agency Rules of Evidence: This is something of a perennial issue, but might nevertheless (or therefore?) warrant some fresh thinking by the Section. One does hear from time to time frustrations by practitioners about inconsistencies across agencies and, more seriously, across ALJs within a single agency. Is there something that can be done to standardize agency evidentiary rules somewhat? Applying the FRE plainly makes no sense, and even the so far as practicable approach probably is misguided, among other reasons, because the ever-malleable so far as does not promote consistency so well. One alternative might be to develop general recommendations about what agencydeveloped evidentiary rules should like, much like ACUS did in 1986. Another alternative, more modest still, would be to require that each agency to promulgate its own evidentiary rules that will be binding for its own ALJs/hearings. Such an approach would preserve agency flexibility, but at the same time promote intra-agency consistency, as well as notice values. 4. Cross-examination: Here too there may be room for improvement. For example, lower courts have not approached Perales very consistently. What should the rule about cross-examination be: You are entitled so long as you ask for it? You are entitled to it whenever the agency will rely/does rely heaving on a document 2 or report whose author you want to cross? One problem with the former approach is that some parties will ask for it too muchnorms of administrative efficiency might counsel against a categorical rule that says you are entitled to cross-examination merely upon the asking. In this light, perhaps ALJs should have a general power to dispense with cross-examination whenever it is considered unnecessary. On the other hand, one problem with the latter approach is that it will not always be clear before the agencys decision how much an agency will end up relying on the evidence in question. There is something chronologically awkward, in other words, about a rule that says you get to cross for evidence an agency weighs heavily in its decision. So what other approach might be practical and feasible? Whatever that is, would not more consistency by courts be desirable for its own sake? For example, it may be possible to fashion some general principle guiding abuse-of-discretion reviewability for failure to allow requested cross-examination. Finally, it might make sense to connect the issue of cross-examination to the concept of prejudice associated with written evidence in 556(d). It appears there is not a great deal of case law shedding light on the prejudice caveat specifically. But clearly the idea of prejudice in this context and the right/opportunity of cross-examination are linked. 5. Alternative Hearing Procedure: Of course, the APA now provides for only one mode of formal hearings. Perhaps the introduction of a second, less formal but not informal species of adjudication is now in order. After all, there is a substantial distance between the rigors of formal adjudication and the vagaries of agency-prescribed informal adjudication. In between, an alternative formal hearing process might entail, for example, only written evidence, without opportunity for cross-examination (but rather a right to respond to evidence in writing), but with oral argument. One question a new formal hearing procedure would immediately raise concerns which cases would be most suitable for the alternative procedure. Even so, the APAs current two-tiered approach to adjudication may be too crude for some types of adjudicatory decisions. 3