Word file - Human Rights Coalition

advertisement

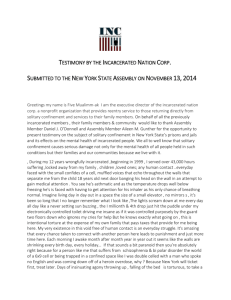

Human Rights Coalition "Abolish Solitary" Platform: Sources and Citations (questions? email bretgrote@yahoo.com) Human beings are social creatures, and we need regular contact with other humans in order to maintain our health, well-being and sanity. Craig Haney and Mona Lynch, Regulating Prisons of the Future: A Psychological Analysis of Supermax and Solitary Confinement, 23 N.Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc. Change 477, 503-06 (1997). 503-04—social contact and the maintenance of “self”: Classic theory and research in social psychology have underscored the importance of social contact for the creation and maintenance of “self.” Indeed, two of the very first social psychologists--Charles Cooley and George Herbert Mead--premised their theories of selfhood entirely upon social interaction. Cooley's evocative term--“looking glass self”--suggested that we look to others and in them see identity-forming reflections of ourselves. [FN120] Mead also emphasized the importance of direct feedback from others in establishing a sense of self, writing that “[w]e appear as selves in our conduct insofar as we ourselves take the attitude that others take toward us . . . .” [FN121] More recently, Leon Festinger's pivotal theory of social comparison processes posited an essential human “drive” for social evaluation that pushes people to belong to groups and associate with *504 others. [FN122] Researchers have documented the importance of social comparison to concepts about the self, [FN123] perceptions of relative deprivation, [FN124] and feelings of equity or fairness. [FN125] In a related series of experimental studies, one social psychologist documented the increased need to affiliate with others in order to interpret emotional states, especially in the face of ambiguous and anxietyarousing situations. [FN126] Subsequent research on this issue added catharsis, interpersonal support, and self-esteem as components of the strong need to be with others--all needs that go unfulfilled when persons are isolated or alone. 505-06—isolation as core feature of “brainwashing” and coercive interrogation techniques: Finally, the importance of social contact in grounding human identity and contributing to mental health is indirectly underscored by the frequency with which isolation is used to create or intensify human malleability. Techniques of coercive interrogation or so-called “brainwashing” virtually always include extreme forms of social isolation. As two students of these techniques wrote: Man is a social animal; he does not live alone. From birth to death he lives in the company of his fellow men. When he is totally isolated, he is removed from all of the interpersonal relations which are so important to him, and taken out of the social role which sustains him. His internal as well as his external life is disrupted. *506 Exposed for the first time to total isolation . . . he develops a predictable group of symptoms, which might almost be called a “disease syndrome.” [FN132] Among the symptoms identified as part of this syndrome were bewilderment, anxiety, frustration, dejection, boredom, rumination, and depression. In addition, the authors observed that “[s]ome prisoners may become delirious and have visual hallucinations.” Depriving a person of nearly all contact with others can cause irreversible psychological damage in as little as 2 weeks. Craig Haney and Mona Lynch, Regulating Prisons of the Future: A Psychological Analysis of Supermax and Solitary Confinement, 23 N.Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc. Change 477, 530 (1997). 530—every study longer than ten days shows negative psychological effects: There is not a single study of solitary confinement wherein non-voluntary confinement that lasted for longer than 10 days failed to result in negative psychological effects. Stuart Grassian, Psychiatric Effects of Solitary Confinement, 22 Wash. U. J.L. & Pol’y 325, 331 (2006). 331—even a few days of solitary: Indeed, even a few days of solitary confinement will predictably shift the electroencephalogram (EEG) pattern toward an abnormal pattern characteristic of stupor and delirium. Peter Scharff Smith, The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature, 34 Crime & Just. 441, 503-04 (2006). 503-04—risk increases daily: “The overall conclusion must therefore be that, though reactions vary between individuals, negative (sometimes severe) health effects can occur after only a few days of solitary confinement. The health risk rises for each additional day in solitary confinement.” Interim Report of the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment U.N. Doc. A/66/268 (August 5, 2011) (Defining solitary confinement in ¶ 26 as “the physical and social isolation of individuals who are confined to their cells for 22 to 24 hours a day.”). ¶ 26—definition of prolonged solitary (15 days): For the purposes of this report, the Special Rapporteur defines solitary confinement as the physical and social isolation of individuals who are confined to their cells for 22 to 24 hours a day. Of particular concern to the Special Rapporteur is prolonged solitary confinement, which he defines as any period of solitary confinement in excess of 15 days. He is aware of the arbitrary nature of the effort to establish a moment in time which an already harmful regime becomes prolonged and therefore unacceptably painful. He concludes that 15 days is the limit between “solitary confinement” and “prolonged solitary confinement” because at that point, according to the literature surveyed, some of the harmful psychological effects of isolation can become irreversible. ¶ 55—stupor and delirium: Research shows that deprived of a sufficient level of social stimulation, individuals soon become incapable of maintaining an adequate state of alertness and attention to their environment. Indeed, even a few days of solitary confinement will shift an individual’s brain activity towards an abnormal pattern characteristic of stupor and delirium. Advancements in new technologies have made it possible to achieve indirect supervision and keep individuals under close surveillance with almost no human interaction. The European Court of Human Rights has recognized that “complete sensory isolation, coupled with total social isolation, can destroy the personality and constitutes a form of inhuman treatment which cannot be justified by the requirements of security or any other reason”. ¶ 62—health risks rise each day: Negative health effects can occur after only a few days in solitary confinement, and the health risks rise with each additional day spent in such conditions. Experts who have examined the impact of solitary confinement have found three common elements that are inherently present in solitary confinement – social isolation, minimal environmental stimulation and “minimal opportunity for social interaction”. . . . There is no research to support prison administrators' claims that solitary confinement serves any rehabilitative purpose; on the contrary, multiple studies confirm that solitary confinement is emotionally, physically and psychologically destructive and greatly reduces a prisoner's chances at successful reintegration into society. Craig Haney and Mona Lynch, Regulating Prisons of the Future: A Psychological Analysis of Supermax and Solitary Confinement, 23 N.Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc. Change 477, 534-35 (1997). 534-35—no evidence that solitary decreases violence: That is, there are no credible or convincing data of which we are aware to suggest that such confinement produces any widespread beneficial effects. In essence, this was the conclusion of an official Canadian study group on “dissociation” that filed a report with the Commissioner of Penitentiaries in the mid-1970s: “Although we recognize the limitations on social sciences in effective change in inmates, we must still acknowledge the lack of substantive rehabilitative or therapeutic value in the concept of segregation.” [FN280] Moreover, since most prisoners eventually will be released from prison, “segregation as it presently exists is not practical. It further enhances the inmate's antisocial attitudes and, in general, constitutes a self-fulfilling prophecy.” [FN281] Another study concluded that the use of solitary was not even effective as a deterrent. Disciplinary incidence rates were not affected among the punished *535 nor among the general population by the length or number of visits to the “hole.” 536—evidence of alternatives: In contrast to the absence of documentation that supermax or solitary confinement “works,” in general or for any particular type of inmate, there is some direct evidence to suggest that other approaches to handling violent prisoners are effective in both reducing levels of institutional aggression and decreasing recidivism among such prisoners upon release. Chad S. Briggs, Jody L. Sundt, Thomas C. Castellano, The Effect of Supermaximum Security Prisons on Aggregate Levels of Institutional Violence, 41 Criminology 1341, 1346 (2003). (Researcher’s note: This study is inherently flawed as it fails to account for levels of staff-on-prisoner violence. In addition, it relies on official prison data. Even with those qualifiers, it fails to demonstrate that supermax confinement reduces violence.) 1341—summary of findings: No support was found for the hypothesis that supermaxes reduce levels of inmate-on-inmate violence. Mixed support was found for the hypothesis that supermax increases staff safety: the implementation of a supermax had no effect on levels of inmate-on-staff assaults in Minnesota, temporarily increased staff injuries in Arizona, and reduced assaults against staff in Illinois. 1367—summary of findings: The findings presented here reveal that the opening of a supermax had no effect on eight of the measures of institutional violence examined across three states. In one of the time series examined, however, the implementation of a supermax was associated with a temporary increase in assaults against staff. Finally, the opening of a supermax was associated with a decrease in assaults against staff in one of the time series examined. Thus, no support was found for the hypothesis that the implementation of a supermax prison reduces aggregate levels of inmate-on-inmate assaults. Mixed support was found for our second hypothesis: The opening of SMU I in Arizona and OPH in Minnesota were not associated with changes in the incidence of violence directed toward staff; the findings associated with the opening of SMU II suggest that this facility may have been temporarily harmful within the Arizona DOC; and the opening of Tamms in Illinois was associated with a significant, against staff. 1370—evidence does not justify use of supermax: Although some question whether the supermax prison can ever be an acceptable response to prison violence, King (1999:182) argues that, in the least, "where prison regimes are so depriving as those offered in most supermax facilities, the onus is upon those imposing the regimes to demonstrate that this is justified." This justification might come in two fundamental forms. First, we might ask whether supermax reduces prison violence, and second, whether alternative methods of control exist. Although the findings obtained here must be buttressed with analyses from other states-and more contextually informed analyses of trend data from the three states studied hereinthis study presents strong preliminary evidence that supermaximum prisons cannot be justified as a means of increasing inmate safety. Our findings with regard to officer safety are more equivocal, but the necessary onus of evidence in support of the use of supermax certainly has not been met here. Felony and Violent Recidivism Among Supermax Prison Inmates in Washington, Lovell & Johnson (This study shows that supermax prisoners in Washington were more likely to recidivate, though it does not demonstrate the reason why this is (i.e. whether that is because supermax prisoners are more prone to violating the law or because conditions of isolation in a supermax increase the risk of unsuccessful reintegration. What the study can be cited for is support that supermax does not help reduce the recidivism rate, which it would if solitary confinement were an effective deterrent to future criminal behavior.) 1. A finding that IMU assignment predicted lower recidivism would suggest that IMU confinement is an effective treatment. Our findings do not support this hypothesis. 2. A finding that IMU assignment does not predict recidivism would suggest either (1) that IMU-provoking behavior and the IMU experience are both neutral; or (2) that the behavior predicts recidivism as a main effect, but this effect is neutralized by the IMU experience. Neither of these hypotheses is supported. 3. We found, with qualifications, that IMU assignment predicts higher recidivism. We may conclude that IMU confinement does not appear to help control recidivism, which advances knowledge beyond its present null state. But we do not know whether the predictive effect is due to the IMU experience or to some psychological process that leads prison staff to see the offender as threatening and which, after release, leads to further criminal aggression. Jamie Fellner, Human Rights Watch OUT OF SIGHT: SUPER-MAXIMUM SECURITY CONFINEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES § I—An Overview (2000). 1—emotionally, physically, and psychologically destructive: At best, prisoners' days are marked by idleness, tedium, and tension. But for many, the absence of normal social interaction, of reasonable mental stimulus, of exposure to the natural world, of almost everything that makes life human and bearable, is emotionally, physically, and psychologically destructive. 4—no data proving deterrent effect: There are, however, other ways to encourage good conduct than to raise the specter of supermax confinement and, to date, there is no data proving such a deterrent effect. Jennifer R. Wynn and Alisa Szatrowski, Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown in New York State Correctional Facilities, 24 Pace L. Rev. 497, 514 (2004) 514—no research in support of control units positive effects: While a large body of literature attests to the damaging psychological effects of long-term isolation, there is no empirical research that shows the opposite: that long-term punitive segregation produces positive changes in behavior. That nearly threequarters of the inmates at Southport had prior stays in disciplinary lockdown clearly undermines the notion that lockdown effectively deters future ruleviolating behavior. In isolation, the mentally ill become more unstable, while healthy prisoners begin to exhibit mental illness after only a short time. Peter Scharff Smith, The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature, 34 Crime & Just. 441, 503-04 (2006). 504—causing harm to all: Solitary confinement harms prisoners who were not mentally ill on admission to prison and worsens the mental health of those who were. Leena Kurki and Norval Morris, The Purposes, Practices, and Problems of Supermax Prisons, 28 Crime & Just. 385, 409 (2001) 409—mentally ill in supermax prisons: Quite apart from whether administrative rules exclude mentally ill prisoners from supermaxes, many such prisoners are held in Tamms, Pelican Bay, Red Onion, and Indiana's and Texas's supermaxes. The chief of medical services estimated that 208 prisoners at Pelican Bay in 1990 were either psychotic or psychotic in partial remission (Madrid v. Gomez at 1215). Stuart Grassian found that seventeen out of fifty inmates he interviewed in the special housing unit were acutely psychotic and not receiving appropriate treatment (Madrid v. Gomez at 1223). The staff of Indiana's special housing unit acknowledged that half to two-thirds of inmates were mentally ill (Human Rights Watch 1997, p. 34). Crisis symptoms of mental illnesses are obvious to everyone: severe self-mutilation, hallucinations, paranoia, panic attacks and anxiety, and impulsive violence (Kupers 1999). Yet descriptions about Tamms, Pelican Bay, Red Onion, and Indiana's and Texas's supermaxes similarly point out that the mental health staff in these supermaxes seemed to be preoccupied with sorting out those inmates they believed were manipulative malingerers who faked their symptoms. All sources describe inmates who suffer serious hallucinations, act absurdly, and are far beyond ordinary human behavior. Jennifer R. Wynn and Alisa Szatrowski, Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown in New York State Correctional Facilities, 24 Pace L. Rev. 497, 514 (2004) 511—desperation on every site visit: The most disturbing aspect of our site visits was encountering so many prisoners in twenty-three-lockdown who were actively psychotic, manic, paranoid or delusional. [FN63] On nearly every site visit, it was not uncommon to encounter individuals in various states of desperation: men weeping in their cells, men who had smeared feces on their bodies or lit their cells on fire, inmates who cut themselves in a form of selfdirected violence known as “self-mutilation.” Some inmates expressed persecutory thoughts--“The COs are poisoning my food”--or believed that the prison psychologist was “drugging” them. Approximately 50% of prison suicides occur in solitary confinement. Cruel and unusual treatment of WikiLeaks suspect, By Terry A. Kupers, Special to CNN - http://articles.cnn.com/2011-03-16/opinion/kupers.bradley.manning.prison_1_solitaryconfinement-prisoners-mental-illness?_s=PM:OPINION “One of the most stunning statistics in criminology today is that, on average, 50% of U.S. prisoner suicides happen among the 2% to 8% of prisoners who are in solitary confinement, also known as segregation.” The Colorado Study vs. the Reality of Supermax Confinement, Stuart Grassian, M.D., J.D., and Terry Kupers M.D, M.S.P., Correctional Mental Health Report, Volume 13 No. 1, May/June 2011 “One of the most stunning and inescapable statistical facts regarding long-term segregation is that on average, 50% of completed suicides by inmates occur among the 2-8% of prisoners who are housed in isolated confinement. This fact can mean only two things: either it demonstrates that segregation is psychologically toxic, or else it demonstrates that the more troubled inmates who need psychiatric help are instead placed in a psychiatrically punitive environment. Of course, it is both: the more psychologically troubled inmates have less control over their behavior, and the system’s response to their unacceptable behaviors is to punish them with isolation.” Cruel Isolation: Amnesty International’s Concerns About Conditions in Arizona Maximum Security Prisons, April 2012 11—higher suicide rate in the hole: “At least 43 suicides are listed as having taken place in Arizona’s adult prisons in the five and a half years from October 2005 to April 2011, with several more cases to June 2011 still under investigation. Of 37 cases where Amnesty International obtained information on the units where the suicides took place, 22 (60%) took place in Maximum custody isolation facilities: SMU1/11 (14 suicides); Florence Central Unit (4); and Lumley Unit (4), which is the special management unit of the women’s prison at Perryville. SMU1/11, which houses 4% of the total state prison population, accounted for more than a third of the 37 suicides.” Jennifer R. Wynn and Alisa Szatrowski, Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown in New York State Correctional Facilities, 24 Pace L. Rev. 497, 514 (2004) 516—suicide statistics: More than half of prison suicides in New York take place in twenty-three-hour lockdown units, although less than 10% of the inmate population is housed in them. [FN78] “Perhaps no factor has been more tragically associated with jail and prison suicides than the consistent finding of isolated/segregated housing,” wrote psychologist Ronald Bonner in the Journal of the American Association of Suicidology. [FN79] Of the 258 inmates in our sample, 44% reported that they had attempted suicide at least once while in prison and 20% had prior admissions to the psychiatric hospital for inmates. These figures are more reflective of a mental hospital than a prison. Solitary confinement targets prisoners of color most severely, reinforcing oppressive and unconscionable patterns of racism. This is known because 1) people of color are incarcerated at far greater levels than their percentage of the general population; and 2) through consistent reports received by HRC about the demographics in the solitary units in PA. This data is also kept under wraps. If the DOC wants to contest it they can release the data and allow access to the units for verification. Mark S. Hamm, Therese Coupez, Frances E. Hoze & Corey Weinstein, The Myth of Humane Imprisonment: A Critical Analysis of Severe Discipline in U.S. Maximum Security Prisons, 1945-1990, in PRISON VIOLENCE IN AMERICA 190 (Michael C. Braswell, Reid H. Montgomery, Jr., Lucien X. Lombardo, eds. 1994) 190—deeply entrenched: “The pattern of guard brutality noted here is consistent with the vast and varied body of post-war literature demonstrating that “guard use of physical coercion [is] highly structured and deeply entrenched in the guard subculture”. The unusually harsh treatment of jailhouse lawyers, blacks, and mentally ill offenders has been confirmed time and again in the literature. And our discovery that maximum security prisons are exceedingly cruel places will surprise no on.” Jamie Fellner, Human Rights Watch, RED ONION STATE PRISON: SUPERMAXIMUM SECURITY CONFINEMENT IN VIRGINIA (1999). Pervasive racism: Unfortunately, white and black inmates alike at Red Onion describe an atmosphere of pervasive and blatant racism. Inmates claim that officers routinely use such terms as “boy” and “nigger”. One white inmate told HRW that an officer said to him, with reference to a black inmate with a reputation for sexual misbehavior, “What do you expect from a fucking nigger?” Another white inmate wrote to HRW that he had talked with an officer escorting him about a shooting. He described the officer as “so excited about being able to shoot ‘niggers...’[H]e couldn’t wait to shoot some of them black bastards.” It is extensively used to retaliate against those who file lawsuits or speak out against violations of their human and constitutional rights. See HRC/Fed Up! reports: Institutionalized Cruelty, Resistance and Retaliation, Unity and Courage for discussions of retaliation. Mark S. Hamm, Therese Coupez, Frances E. Hoze & Corey Weinstein, The Myth of Humane Imprisonment: A Critical Analysis of Severe Discipline in U.S. Maximum Security Prisons, 1945-1990, in PRISON VIOLENCE IN AMERICA 190 (Michael C. Braswell, Reid H. Montgomery, Jr., Lucien X. Lombardo, eds. 1994) 187—jailhouse lawyers targeted: “Table 10.8 shows that the primary victim of severe discipline is not a black man or woman, as might be suspected. The primary victim is not Hispanic, and certainly is not a gang member nor a political prisoner. The primary victim is not a homosexual or one suffering from AIDS. Rather, Table 10.8 reveals that the primary victim of severe discipline is a jailhouse lawyer.” 188—why jailhouse lawyers are targeted: “We received hundreds of comments from prisoners explaining why jailhouse lawyers are differentially treated. These responses typically began with the assertion that prison officials “ignore grievances” and the “inmate appeal system is a farce” because of unfair hearings and arbitrary discipline systems” base on “no true trial” or a “biased hearing.” They proceeded to the idea that there were “inconsistent and ever-changing rules” that were “vague” and “applied based on guards opinion of you.” And so, these respondents arrived at the conclusion that there was “selective discipline with racial prejudice” and that “jailhouse lawyers can help you out of a jam.” . . . Because of this, these respondents observed that guards had a standard practice of “singling out jailhouse lawyers for discipline” in retaliation for challenging the status quo.” 190—deeply entrenched: “The pattern of guard brutality noted here is consistent with the vast and varied body of post-war literature demonstrating that “guard use of physical coercion [is] highly structured and deeply entrenched in the guard subculture”. The unusually harsh treatment of jailhouse lawyers, blacks, and mentally ill offenders has been confirmed time and again in the literature. And our discovery that maximum security prisons are exceedingly cruel places will surprise no on.” “One of the Dirty Secrets of American Corrections”: Retaliation, Surplus Power, and Whistleblowing Inmates, 42 U. Mich. J.L. Reform 611, 613 (2009). 611—normative response to grievance-filing: Retaliation is deeply engrained in the correctional office subculture; it may well be in the normative response when an inmate files a grievance, a statutory precondition for filing a civil rights action. 613—not rogue actors: Correctional officers who retaliate against inmates cannot be regarded as rogue actors. They act within the norm. Vincent Nathan's groundbreaking survey of Ohio inmates found that 70.1% of inmates who brought grievances indicated that they had suffered retaliation thereafter; moreover, 87% of all respondents *614 and nearly 92% of the inmates using the grievance process agreed with the statement, “I believe staff will retaliate or get back at me if I use the grievance process.” [FN18] Among staff supervisors, only 21% believed that retaliation never happened, with one warden characterizing it as “commonplace” when inmates resort to the grievance process. [FN19] In turn, a New York State study found that more than half of the inmates filing grievances reported subsequent retaliation. 644—PLRA encourages retaliation: Through its exhaustion requirement, the Act has favorably influenced the cost-benefit ratio of correctional officer retaliation by enhancing the benefit. First, the filing of a grievance identifies targets who may seek judicial relief for officer misconduct. Second, retaliation against the targets acquires a functional quality, to wit, the prospect of deterring the target from filing suit and deterring other inmates from filing grievances. Third, by forbidding damages for mental or emotional suffering absent a causallyrelated physical injury, [FN264] the Act effectively immunizes retaliatory measures from compensatory damage awards if they stop short of physical injury. 645—prisoners as whistleblowers: Inmates who file grievances about matters of public importance become the penal counterpart of civilian, governmental whistleblowers. The two groups share several characteristics. Like whistleblowers, inmates experiencing retaliation sometimes possess information that has not been disseminated publicly; like whistleblowers, inmates acquire this information because of their institutional membership; and inmates and whistleblowers alike function as intermediaries by providing information to a third party, be it a government watchdog agency, a court, or, because of the exhaustion requirement of the PLRA, a grievance officer. [FN268] Furthermore, both whistleblowers and inmates face retaliation because they reside in institutions that do not readily tolerate dissent. Ninety days in solitary can easily turn into 10 years or more. Another fact known from HRC’s own work with prisoners who are placed in solitary confinement and quickly accrue disciplinary time amounting to several months or even a couple of years, which sets off a cycle of protest, abuse, retaliation, and so on. Again, if the DOC wants to contest this, all they have to do is release records of who is in solitary, how often that person has been there, and for how long. Guards in these units regularly abuse male and female prisoners physically, psychologically, and sexually, and deny them basic needs such as meals, shower, water, and visits. See HRC/Fed Up! reports: Institutionalized Cruelty, Resistance and Retaliation, Unity and Courage for discussions of retaliation. Also see virtually any edition of the PA Prison Report. Craig Haney and Mona Lynch, Regulating Prisons of the Future: A Psychological Analysis of Supermax and Solitary Confinement, 23 N.Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc. Change 477, 531 (1997). 531—an integral part of the experience: Commentators who have sought to attribute these harmful consequences not to isolation per se but to mistreatment by guards and to the loss of educational, vocational, and recreational activities by prisoners [FN269] seem to ignore the extent to which these practices regularly occur in solitary confinement. Greater exposure to staff mistreatment and the loss of meaningful programming cannot be characterized as unfortunate but merely occasional incidents to solitary confinement; they are too often an integral part of the experience. Leena Kurki and Norval Morris, The Purposes, Practices, and Problems of Supermax Prisons, 28 Crime & Just. 385, 408-09 (2001) 408-09—a culture that supports abuse of power: Observations of relations between the staff and inmates vary from “considerable hostility” in Tamms and “unusually hostile” in Red Onion (Human Rights Watch 1999, p. 20) to an “affirmative management strategy to permit the use of excessive force” in Pelican Bay (Madrid v. Gomez at 1199). All the characteristics of supermaxes are more likely than not to create a culture that supports abuse of power. Inmates are labeled as the worst of worst and are isolated from other inmates. The staff have practically unlimited power to control inmates' access to food, possessions, and movement. Any humane relationships between staff and inmates are rare in circumstances where interaction is limited to the most dangerous situations— extracting inmates from cells or escorting shackled and handcuffed inmates to showers, exercise yards, visiting areas, or medical care (Ward 1995). Supermaxes are far removed from the usual sights, sounds, standards, and restrictions of everyday prison life and far removed from the perception of the outside *409 world. The physical and intellectual isolation “helps create a palpable distance from ordinary compunctions, inhibitions, and community norms”—for both the staff and prisoners (Madrid v. Gomez at 1160). 409—supermax more likely to produce violent staff: No one knows how common abuses of power or the use of excessive force are in supermax prisons. However, many agree that supermax regimes are more likely than other prison regimes to produce abusive and violent behaviors by the staff. Pelican Bay in the early 1990s must have been among the worst examples with a deliberate pattern of violence and excessive force, but unspeakable incidents are also described in Ruiz v. Johnson on Texas administrative segregation units and in Human Rights Watch (1997, 1999) reports on Red Onion and Indiana's supermaxes. Jamie Fellner, Human Rights Watch OUT OF SIGHT: SUPER-MAXIMUM SECURITY CONFINEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES § I—An Overview (2000). 4—abuse flourishes: There is a heightened risk in supermax facilities that correctional officers will use abusive levels of force. They work in an environment in which the usual prison "us vs. them" mentality is exaggerated by the minimal staff-inmate interaction, the primacy of security over all other considerations, and the fact that the inmates have been demonized as "the worst of the worst." Perhaps not surprisingly, correctional officers in some supermax facilities have repeatedly crossed the line between the legitimate use of force and abuse. They have used force -- including cell extractions and the discharge of electronic stun devices, stun guns, chemical sprays, shotguns with rubber pellets and even guns loaded with lethal munitions -- unnecessarily, dangerously, and even maliciously. Jamie Fellner, Human Rights Watch, RED ONION STATE PRISON: SUPERMAXIMUM SECURITY CONFINEMENT IN VIRGINIA (1999). Guard on inmate violence: As one inmate wrote to Human Rights Watch, “Frankly, in many ways, it is safer to be in the segregation unit than in the so-called general population. Inmate on inmate violence virtually does not exist [at Red Onion]. Inmate on guard violence virtually does not exist here. Guard on inmate violence is high.” Unusually hostile: Conditions in super-maximum security prisons tend to foster unusually hostile relations between prisoners and guards. The simple fact that prisoners have been labeled the “worst of the worst” and are subject to extreme controls and have minimal and highly structured interaction with staff encourages correctional officers to view them in a dehumanizing way and to treat them more harshly. Reliance on threat and use of force: To date, nobody has been killed at Red Onion. But Red Onion is a facility that appears to be managed by reliance on the continual threat and actual use of physical force, including firearms, electronic stun devices, chemical sprays and restraints. From the information available to us, it seems that physical force is used unnecessarily and excessively at Red Onion. Inmates claim that they are shot at, shocked with electronic stun devices, beaten, and strapped down for trivial nonviolent actions, e.g., moving slowly on the yard, yelling in the cells, refusing to return a paper cup. Restraints and strip cells: Inmates also claim Red Onion staff abuse restraint equipment and strip cells, using them maliciously as punishment even though such use is prohibited. Four- and five-point65 restraints immobilize an inmate on a bed. They should only be used in extreme circumstances—when an inmate left unrestrained poses a serious risk of injury to himself or to others and when other types of restraints are ineffective—and for no more time than is absolutely necessary.66 Inmates assert, however, that staff at Red Onion place men in restraints as retaliation for misbehavior, e.g. throwing juice on an officer. “[E]veryone here knows it’s for punishment.” They also assert that inmates are kept in restraints for arbitrary time periods—eight hours, seventy-two hours—regardless of the inmates’ condition or the need for such control. Inmates have similarly complained that strip cells containing no furnishings, bedding or equipment are used as punishment. The degrading nature of unnecessary strip cell confinement is heightened by officers’ refusal to provide toilet paper when needed. Jennifer R. Wynn and Alisa Szatrowski, Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown in New York State Correctional Facilities, 24 Pace L. Rev. 497, 514 (2004) 525—breeding grounds for sadistic behavior: Because of the isolated nature of lockdown facilities, there is great potential for misuse of authority and abuse of inmates and staff. Without careful measures to mitigate against these factors, lockdown units can become breeding grounds for sadistic behavior, fatal neglect and callous indifference to human suffering. At least 80,000 prisoners today are held in solitary confinement in the U.S., at least 2,500 of them in Pennsylvania state prisons. Jean Casella and James Ridgeway, How Many Prisoners Are in Solitary Confinement in the United States? February 1, 2012, accessed at http://solitarywatch.com/2012/02/01/how-many-prisoners-are-in-solitary-confinement-inthe-united-states/). “A census of state and federal prisoners is conducted every five years by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics. The most recent census for which data are available is 2005. It found 81,622 inmates were being held in “restricted housing.” This number was recently cited by the Vera Institute of Justice‘s Segregation Reduction Project. The 80,000 figure has also been used by National Geographic and The New Yorker, among others.” PA Figure is found in the recent PA DOC Monthly Population Reports when the numbers in the RHU and SSNU are totaled. It is unclear if the RHU figures include those in SMUs and death row, which are also characterized as RHUs. Most have little or no access to mental health care, and are forced to live in conditions that increase the likelihood of self-harm, suicide, and violence towards others. HRC is aware of the general lack of meaningful mental health care through our extensive investigations and documentations. This is a point raised consistently in the relevant scholarship and can be inferred from some of the above points on mental health, such as the suicide rates. Jennifer R. Wynn and Alisa Szatrowski, Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown in New York State Correctional Facilities, 24 Pace L. Rev. 497, 514 (2004) 517-18—punishment for self-mutilation: Department figures show that incidents of self-harm rose by 49% between 1995 and 2000. [FN92] Of the inmates in our sample, *518 36% said they engaged in self-mutilation while in prison. Unthinkable to outside observers, DOCS issues misbehavior reports to inmates who attempt to kill or harm themselves, purportedly to discourage malingering. The act of “inflicting self-harm” is an official violation of DOCS policy. [FN93] To punish individuals in such desperate straits can only be described as cruel and misguided. 518-19—staff confession: When we returned to Southport in May 2002, correction officers asked to meet with us privately off facility grounds for fear of reprisal from the superintendent. They reported that, *519 “the biggest problem is that a quarter of the inmates are mentally ill and shouldn't be here.” [FN96] Two psychologists share a caseload of 130 inmates. All of the officers said that they knew of inmates who manifested obvious signs of mental illness but who were not on the OMH caseload. [FN97] They also stated: “The administration heard you were coming and moved the worst inmates out.” This danger ripples outward when prisoners who have been kept in solitary are released into general population, often resulting in violent altercations that are used as a justification to continually cycle them back into solitary. Leena Kurki and Norval Morris, The Purposes, Practices, and Problems of Supermax Prisons, 28 Crime & Just. 385, 404 (2001) 404—cycle of repression: There is a more insidious aspect of the processes that put the mentally ill in jails, prisons, and supermax prisons. More than the community at large, the criminal justice system and those who serve it rely on deterrence as a system to control human behavior. A substantial proportion of those who suffer from mental illness, or who are marginally retarded, or who tremble on the brink of those conditions tend to respond unfavorably and with increasing resistance to punitive controls. The supposed equilibrium of misbehavior and deterrent punishment is thus ratcheted up step by step so that the inadequate and troubled personality may be jailed for a minor offense and by virtue of an increasing process of deterrent punishment, increased resistance, increased deterrent punishment, yet further increased resistance, the result is a stepping up through the graduated severity of different prisons to the ultimate location in a Tamms. Jennifer R. Wynn and Alisa Szatrowski, Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown in New York State Correctional Facilities, 24 Pace L. Rev. 497, 514 (2004) 512-23—revolving door of dysfunction: Inmates who are transferred to CNYPC from disciplinary confinement are often returned to lockdown rather than to general population to serve out the remainder of their disciplinary sentence. In a cycle an outside psychiatrist described as a “misery-go-round,” the inmate typically deteriorates again, is returned to CNYPC, stabilized temporarily, sent back to the SHU, and the grim cycle continues. [FN68] Psychiatrist Stuart Grassian, one of the country's leading experts on the psychological effects of solitary confinement, was appointed by the court in *513 Eng v. Goord to monitor conditions in the Attica SHU. He commented on the ongoing nature of this problem after a site visit in 1999: [T]he “revolving door” of decompensation in SHU leading to brief respite and then return to the toxic SHU environment, continues basically unabated. Mentally ill inmates continue to be housed in SHU even after they have recurrently become floridly ill and out of control in that setting. OMH's failure to intervene in this reality--its failure to state that there are individuals incapable of tolerating Attica SHU--pulls OMH staff away from professional integrity, and towards a hostile, cynical attitude towards those inmates. People max out their sentences in solitary confinement, and then without any resocialization therapy are dumped back into society, harmed and unable to cope, resulting in increased violence and instability in our communities. *PA recidivism rates Felony and Violent Recidivism Among Supermax Prison Inmates in Washington, Lovell & Johnson (This study shows that supermax prisoners in Washington were more likely to recidivate, though it does not demonstrate the reason why this is (i.e. whether that is because supermax prisoners are more prone to violating the law or because conditions of isolation in a supermax increase the risk of unsuccessful reintegration. What the study can be cited for is support that supermax does not help reduce the recidivism rate, which it would if solitary confinement were an effective deterrent to future criminal behavior.) 1. A finding that IMU assignment predicted lower recidivism would suggest that IMU confinement is an effective treatment. Our findings do not support this hypothesis. 2. A finding that IMU assignment does not predict recidivism would suggest either (1) that IMU-provoking behavior and the IMU experience are both neutral; or (2) that the behavior predicts recidivism as a main effect, but this effect is neutralized by the IMU experience. Neither of these hypotheses is supported. 3. We found, with qualifications, that IMU assignment predicts higher recidivism. We may conclude that IMU confinement does not appear to help control recidivism, which advances knowledge beyond its present null state. But we do not know whether the predictive effect is due to the IMU experience or to some psychological process that leads prison staff to see the offender as threatening and which, after release, leads to further criminal aggression. The practice of solitary confinement is widespread, is significantly more expensive than regular prison housing . . . See fact sheet compiled by Solitary Watch: http://solitarywatch.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/fact-sheet-the-high-cost-of-solitaryconfinement.pdf Although there is no PA-specific data that HRC is aware of, the pattern reflected in the fact sheet makes clear that the costs are significantly higher. The rampant use of solitary confinement and the construction of Supermax prisons are recent in history . . . Leena Kurki and Norval Morris, The Purposes, Practices, and Problems of Supermax Prisons, 28 Crime & Just. 385 (2001) 385—tracking the rise: In 1984 there was only one prison in the United States that would now be called a “supermax”—the federal penitentiary at Marion, Illinois, after the October 1983 lockdown. In 1999, by various counts and various definitions, between thirty and thirty-four states had supermax prisons or units, with more building apace (National Institute of Corrections 1997; King 1999). . . . other states have already taken steps to reduce its use. *Maine, Colorado, Mississippi