file

advertisement

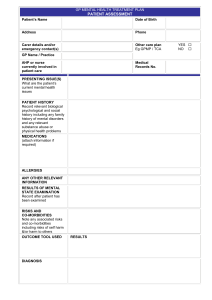

Islamic Republic of Afghanistan National Drug Treatment Guidelines February 2006 Drug Demand Reduction Directorate Drug Demand Reduction unit Ministry of Counter Narcotics Ministry of Public Health Table of Contents Preface page Introduction Background Main Drug used in Afghanistan Towards a Comprehensive Drug treatment service and continuum of care The Continuum of Care Assessment and Pre-treatment Pre-treatment Motivational Counseling Drug Reduction Program Harm Reduction Program Detoxification Treatment and Rehabilitation Aftercare Follow up Harm Reduction Monitoring and Evaluation Special Needs Groups Program Management Appendix 1: Harm Reduction for IDUs Appendix 2: Stage of Changes and Relevant Interventions Pre-Contemplation Contemplation Decision Action Maintenance Relapse Appendix 3: Relapse Prevention Reference 1 2 2 3 3 4 5 5 5 5 6 6 6 7 7 7 8 9 9 10 10 10 10 10 11 11 12 Drug Treatment Guidelines for Afghanistan Developed by Demand Reduction Directorate of the Ministry of Counter Narcotics in conjunction with the Treatment Sub-group of the National Demand Reduction Working Group November 2005 1. Introduction: The following are a set of guidelines for the development of drug treatment projects and programmes in Afghanistan. As far as possible given scarce resources and other constraints, all organizations and agencies, national and international, government, NGO and private, should follow these guidelines that will be used by the Ministry of Counter Narcotics as a basic set of principles to monitor all drug treatment services and facilities. 1.1 Regardless of which method of treatment is used, it is the responsibility of all individuals and organizations involved in the provision of drug treatment to ensure that the changing needs of the client are met and that where appropriate responsibility is taken for moving the recovering drug user to the next appropriate stage of treatment. 1.2 In order to develop a comprehensive system of care and support that takes a multidisciplinary approach, and to reduce the risk of relapse, an integrated treatment programme should be able to offer the following services: pre-treatment; detoxification; treatment; rehabilitation, aftercare; follow-up and a range of outreach/family/community-based initiatives. Harm reduction services can be integrated into such a programme, although they can also offer a separate service for clients not motivated to stop using drugs. 1.3 Within each area of treatment there are different methods of working and each organization must decide for itself which method is the most appropriate to meet the needs of their client groups based on comprehensive individual client assessments. An agency may not provide all treatment options, but should then ensure that provision for other necessary services can be identified and appropriate client-referrals made. For example, an agency offering only detoxification and treatment services should make provision for aftercare and relapse prevention services from partner agencies. 1.4 While the guidelines are not prescriptive, each drug treatment service provider should try and follow them to ensure that minimum basic standards meet the needs of clients. For purposes of government data collection and monitoring, a common standard initial client assessment form will be developed that all agencies will have to complete. Agencies are also at liberty to develop their own forms, although completion of government forms will be mandatory. 1.5 The guidelines also provide a set of basic minimum standards relating to the managerial, administrative and staffing work practices of any organization providing drug treatment services in Afghanistan. 1.6 The guidelines should be reviewed on a regular basis. More detailed practice guidelines should be developed for each section as required, for example: standard client assessment form; optional detoxification regimes. 1 2. Background 2.1 Decades of war and conflict have left Afghanistan with an increasing number of problem drug users and few available treatment services. Until mid-2002 the only remaining drug treatment facility in the country was the Government’s Drug Dependency Treatment Centre (DDTC) situated in the Mental Health Department of the Polyclinic in Kabul. Since then, dedicated treatment services offering a range of basic residential, community and outreach services have opened in Kabul, Jalalabad, Faisabad, Gardez, Qandahar and Herat, although these are all under resourced and unable to meet client demand. 2.2. A range of NGOs and other organizations have become involved in providing complementary services for drug users, for example the provision of vocational training and income generation opportunities during rehabilitation, and in training programmes for the development of treatment services, for example training for harm reduction service delivery. Inter-agency cooperation in these areas is to be encouraged. 2.3 There are only a few community based prevention, treatment and outreach services in Afghanistan, in Kabul, Logar and Nangarhar. More services offering a range of harm reduction and social welfare services such as provision of food, first aid, medical care and bathing and washing facilities, as well as information and counseling, are urgently needed. 2.4 One continuing problem in Afghanistan, partly as a result of the Taliban policy of extreme criminalization of drug users and partly due to traditional attitudes towards drug users, is making contact with problem drug users who remain a largely socially invisible, isolated and marginalized group. This is particularly the case for those drug users who may be injecting their drugs. 3. Main drugs used in Afghanistan 3.1 In assessing the needs of individual problem drug users, treatment providers need to be aware of the short-term and long-term effects and consequences, both physical and psychological, of the different drugs consumed, including the methods by which they are taken. Most drug users in Afghanistan present with problems relating to the use of opiates such as heroin and opium, various preparations of cannabis, and a wide range of pharmaceutical drugs, particularly tranquillisers and painkillers. 3.2 The most commonly reported pharmaceutical drugs misused include pentazocine (Sosegon), diazapam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), pheniramine (the anti-histamine Avil), hyoscine, metamizole/dipyrone (Novalgin), buprenorphine (Temgesic), phenobarbitol and other barbiturates. It should be noted that the use of pentazocine has been banned in several countries and that in the UK, “its prescription is now semi-officially discouraged owing to the extra stress it places on the heart and its tendency to create ‘hallucinations and thought disturbances’”.1 The use of methaqualone (mandrax), a non-barbiturate sedative/ hypnotic that has been banned in most western countries because of its powerful effects and high potential for abuse has also been reported. 3.3 Alcohol and solvent users have also reportedly presented to treatment services. Currently there are few reported cases of the use of stimulant drugs like amphetamines, but treatment 1 2 Andrew Tyler, 1995, Street Drugs, Hodder and Stoughton, London, p280 services should be aware of the effects of these types of drugs and appropriate treatment modalities. 3.4 One particular problem is that of polydrug use where a drug user consumes two or more drugs together, or in quick succession, as this can present problems when it comes to the detoxification stage. 4. Towards a comprehensive drug treatment service and continuum of care A comprehensive drug treatment service and continuum of care will include a wide range of treatment options and choices depending on the assessed and changing needs of the drug user. While Afghanistan is a country with few resources, in the long-term it needs to develop a range of options if abstinence from drug use is to be achieved, relapse prevented, drug-related harm reduced and the drug user fully reintegrated into the society. Some features of such a comprehensive service include: Integrated treatment, prevention and harm reduction programmes that will reduce the risk of infectious diseases and other medical and social harm, including drug-related deaths. Afghanistan already has a National Harm Reduction Strategy for IDU (Injecting Drug Use) and HIV Prevention and this should be referred to when developing harm reduction programmes. Community based and outreach harm reduction services that include needle and syringe access and disposal programmes, drug substitution therapy, basic medical provision and first aid, and coordination with social services. (See Appendix 1 for harm reduction with injecting drug users). Government and NGO treatment services should complement each other and develop client referral systems at local, provincial and national levels. Community based/outreach treatment services, including home-based detoxification and treatment, and residential treatment centres. Integration of specialist drug treatment services with generic primary healthcare services eg local health clinics, TBAs (Traditional Birth Attendants), Community Healthcare Workers. Where appropriate the inclusion of existing community groups in the rehabilitation and aftercare of the recovering drug user, for example Mosques, the family and community associations. All staff involved in treatment provision should be comprehensively trained, including basic counseling, basic first aid and basic health and hygiene procedures. Development of comprehensive treatment teams that ideally should have the following multi-disciplinary staff team: medical doctor; nurse; psychiatrist; social workers; psychologist; counselors; peer educators; community outreach workers; trained community volunteers (note that the last 3 groups should utilize ex-drug users where possible) 5. THE CONTINUUM OF CARE It is the responsibility of treatment agencies to ensure that drug users have access to a wide range of services depending on assessed need. Where appropriate this means being able to refer the 3 drug user to another agency that can provide the necessary treatment option. For example, an agency providing mainly detoxification and treatment should establish links with other agencies offering good aftercare and support services. To this end, referral systems and cooperative networks of treatment service providers need to be developed at the local, regional and national levels. Only then can the needs of the various client groups be met. 5.1. Assessment and pre-treatment Before the treatment plan/programme can be developed, a detailed assessment for each individual drug user is required. For drug-dependent clients in particular a range of pre-treatment services can be offered, for example motivational counseling, drug reduction programmes and harm reduction services. 5.1.1 Assessment: A full assessment of the presenting drug user is necessary for the following reasons: To treat any emergency or acute problem. Confirm patient is taking drugs (history and examination – see below). Assess degree of dependence. Identify complications of drug misuse and assess risk behaviour. Identify other medical, social and mental health problems. Give advice on harm reduction, including, if appropriate, access to sterile needles and syringes, testing for hepatitis, HIV and immunisation against hepatitis B. Determine the patient’s expectations of treatment and the degree of motivation to change. Assess the most appropriate level of expertise required to manage the patient (this may alter over time), and refer/liaise appropriately, for example to residential centre for detoxification and treatment or for home-based detoxification. Determine the need for substitute medication if any. Record all assessment details on a standard reporting form. A recorded drug history: This should include sections on the following: Reason for presentation/method of referral Past and current (last 4 weeks) drug use Method of drug use (eg smoking, ingesting, sniffing, injecting) History of injecting and risk of HIV and hepatitis Medical history Psychiatric history Social history eg family situation, employment record, educational level, vocational skills Past contact with treatment services Examination: 4 Assessing motivation Assessing general health Assessment of mental health Assessment of family and social situation 5.1.2 Pre treatment motivational counselling: Ideally there should be a 5-30 day period of motivational counseling before a drug-dependent client is admitted for detoxification and treatment. This can be done in a centre or in the community and preferably should be conducted in small groups (as with Nejat Centre’s Hujra system). Such counseling can be done on a daily, twice weekly or weekly basis depending on circumstances and the duration of the pre-treatment programme. Staff engaged in motivational counseling should be thoroughly trained in the techniques involved (see Appendix 2 for Stages of Change Model). 5.1.3 Drug reduction programmes: Depending on the motivational level of the drug user a drug reduction programme should be considered for those entering the detoxification stage. This can also be seen as a slow detoxification, allowing users to gradually reduce their daily consumption of drugs at a realistic and manageable pace. 5.1.4 Harm Reduction services: See section 5.6 5.2. Detoxification: 5.2.1 A detoxification and treatment programme should be developed for each recovering drug user depending on their need. The method of detoxification will depend on the needs of the individual client. Currently symptomatic treatment is usually provided during detoxification using minor painkillers, but a problematic client group such as IDUs or barbiturate users may need to be detoxified using substitute opiates or non-opiate drugs. Barbiturate users are at particular risk and need to be closely monitored and supported during detoxification. 5.2.2 For some individuals, general support, understanding of the symptoms associated with drug withdrawal and encouragement may be enough. Symptomatic relief of withdrawal symptoms can sometimes be achieved with minor painkillers and/or tranquillisers if necessary. 5.2.3 Some clients may have a history of self-recovery where they have previously given up drugs without any outside help or intervention, perhaps because of shifts in identity and lifestyle, family pressure, change in financial circumstances or unavailability of drugs. It is useful exploring with the client their previous experiences, if any, of withdrawing from drugs, whether in a treatment facility or by themselves. 5.2.4 For some drug-dependent clients a history of serious withdrawal complications (e.g. benzodiazepine or alcohol withdrawal-induced epileptic fits), or a lack of social support or other problems, may make substitute prescribing necessary during the detoxification process. It is best to assume that any drug that has been heavily consumed over a significant period of time may have a withdrawal-symptom profile associated with it. Withdrawal symptoms will differ depending on the pharmacological profile of the drug user. Some drugs with short half-lives will give rise to withdrawal symptoms at an earlier phase: the symptoms will also peak, and be cleared, quicker. 5.2.5 The severity of withdrawal symptoms is not clearly or directly related to the quantity of drugs previously consumed. When assessing withdrawal, for the purpose of dose titration, it is better to place greater weight on observable signs rather than subjective symptoms. In 5 Afghanistan clients undergoing detoxification may suffer from malnutrition and endemic illnesses like TB, hepatitis and bronchitis, and these need to be factored in. 5.2.6 Medically supervised detoxification programmes for management of withdrawal symptoms and stabilization can be carried out in a residential setting or in the community, particularly the home if there is a supportive family arrangement. The detoxification stage of treatment can last from 5 to 14 days depending on individual needs. 5.2.7 Treatment of the heroin withdrawal syndrome can be given using substitute opiates such as methadone, buprenorphine, or codeine-based drugs. Non-opiate drugs such as clonidine, naltrexone and lofexidine can also be used, but only by staff who have been specifically trained in this treatment option. 5.3. Treatment and rehabilitation: 5.3.1 The treatment and rehabilitation stage of the recovery cycle can take place in either inpatient residential or outpatient community facilities for a period of 1 to 3 months, depending on the needs of the client and whether family support is available. During this period recovering drug users should receive counseling, including relapse prevention (see Appendix 3), be encouraged to make lifestyle changes and engage in recreational activities, sports, life skills enhancement training, work programmes and other healthy activities. All treatment services should have available a basic documented treatment programme for their clients. 5.4. Aftercare: 5.4.1 This phase of treatment should be for a longer duration that can last for up to 2 years depending on the client’s needs. During this period regular counseling sessions and meetings should be arranged with the client either in the treatment centre or in the community. In Afghanistan this can be problematic as a recovering drug user may return to their home in a different province after the detoxification and treatment stage. All efforts must be made by the treatment service to contact and support the user’s family and any other source of community help and assistance such as Mosques and support groups. 5.4.2 Self-help/support groups of ex-drug users can provide a very useful support to the recovering user, and treatment services should try and develop and encourage these groups. Attempts should also be made to employ ex-drug users as treatment counselors, particularly for community and outreach work. 5.4.3 In an impoverished country like Afghanistan it is very important that vocational training and other income generating opportunities are provided during this stage, and even during the treatment and rehabilitation stage, as this is essential for social reintegration. If this cannot be provided by the specialist treatment agency, and there is no reason why it should, then the agency must make arrangements with NGOs and Government offices to provide such services to recovering users. Networking and establishing partnerships with other non-treatment agencies at this stage can play a very important role, for example work and vocational training schemes run by the Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs, UN organizations and NGOs. 5.5. Follow-up 5.5.1 While follow-up and aftercare are often combined, aftercare emphasizes the continued provision of services to recovering drug users, such as counseling, family support, vocational 6 training and income-generation opportunities. Follow-up is more a long-term stage when the recovering drug user is contacted to check on his progress and to determine whether he is still drug-free. Collecting data at this stage to determine relapse rates is important. This process can be facilitated by the provision of good family support and self-help groups such as NA (Narcotics Anonymous). 5.6. Harm reduction: 5.6.1 A defining feature of harm reduction is the focus on the prevention of drug-related harm for those drug users unable or unwilling to stop using drugs. This includes reducing harm at the individual, family and community levels, and reducing different types of harm such as health, social, financial and legal. 5.6.2 A core package of harm reduction interventions will include the following: Sterile needle and syringe access and disposal programmes Information on safer injecting practices Provision of condoms Provision of information, advice and education about HIV, other diseases and good sexual and reproductive health Substitute drug therapy Counseling services These interventions may be associated with clients that are unable to satisfy basic needs such as food, shelter and hygiene toward which supporting arrangements should be considered and coordinated. To promote accessibility, the package is best delivered through community based interventions by clinics and outreach services. 6. Monitoring and Evaluation 6.1 While the MCN has the national government responsibility for coordinating and monitoring all treatment activities in Afghanistan, in conjunction with the Ministry of Public Health, and is in the process of developing recording tools for this purpose, all treatment agencies need to actively monitor, record and evaluate their own practices in order to improve services to the client group and also to provide necessary information to donors. 7. Special needs groups: 7.1 There are several high-risk groups in Afghanistan where special services may need to be developed because of presenting problems and risks during treatment, for example with pregnant women during the detoxification stage; homeless people after detoxification and completing residential treatment; and drug users with mental health problems. Some examples of special needs groups: 7 Women and pregnant users Poly drug users Injecting drug users Children and juveniles Ex-combatants Prisoners The Homeless Dual diagnosis (Drug use and mental health problems) 8. Programme Management Programme specifications are necessary for all drug treatment programmes to ensure that their purposes and operational procedures are: publicly transparent; clearly linked to some aspect of the drugs problem; and, supported by the management and administration of appropriate human, material and financial resources. The specifications can also provide a reference point for service adaptation as the nature of drug problems inevitably change over time. Furthermore they provide important information for interagency referral and for more effective planning in the development or adaptation of the treatment continuum. The following specifications should be evident in each drug treatment programme and should constitute a written policy and strategy document available for monitoring purposes: 8 A description of the client group that is served by the programme; An operational philosophy that defines the preferred treatment model together with the specific approach that is used and how it can lead to a successful outcome; Standards of governance in a description of the executive and operational management structure of the programme and how it is regulated; Strategic management by outlining an overall mission statement and a strategic plan; A description of the size and composition of the staff team; Access and referral information with a clear description as to how referrals are made to the programme, the time limits for a response, what staff will be involved and how the referral will be managed, how the referral process will be documented, and what outcomes will be communicated back to the referring agency; A description of the assessment criteria, including method as to how the client will be assessed and what specific problems will be screened for and assessed; Care planning and review that provides a written description of the treatment to be provided and its predicted course, including the specific needs of the client and the way they will be addressed by the service or by other service providers. This process needs to be carefully monitored and revised as necessary. Completing treatment as a planned event, including onward referral if necessary and overseen by a designated staff member; Human resources management and development, including a manager, staff and volunteers (if used) that are recruited in an open and transparent procedure to acquire the skills and abilities relevant to written job descriptions and the programme objectives. Provision should also be made for the supervision and appraisal of staff performance together with an annual training plan that has financial support. Health and safety provisions, including procedures for disruptive or threatening behavior, partnered outreach staff with backup communications – especially when working in a new setting, and procedures to prevent the spread of communicable diseases. Premises will need to meet the requirements of appropriate regulatory bodies, including provisions to secure any inventory of psychotropic drugs; Accommodation that should be comfortable and meet the needs of clients with regard to their privacy, dignity, and respect. Food and drink should be nutritious and healthy; Programme performance and quality should be addressed with procedures for documenting and reporting service outputs and outcomes; Other core operational procedures should be established for: admission and discharge criteria; client rights; client confidentiality; client participation; complaints procedure; and, visitors policy. Appendix 1: Harm Reduction for IDUs (Injecting Drug Users) Injecting drug use carries a significant risk of infection not only for the drug user but for his family and other community members, as well as treatment staff, particularly when equipment is shared or not properly cleaned. Dirty and unhygienic injecting habits can result in local or systematic infections, and poor injecting technique can cause venous or arterial thrombosis. The first principle of reducing harm should be to stop injecting practice. The consequences of sharing any injecting equipment (spoons, water, filters, needles, syringes etc.) must be addressed with every misuser. As drug misusers may resort to cleaning of equipment, it is good practice to advise them of the best method they might follow, even allowing for its potential risks. Injectors should be informed of the dangers of using used injecting equipment, and encouraged to be scrupulous in their hygiene technique if injecting drugs. They should be advised to use sterile or at least their own equipment on each occasion, if they are to reduce their risk of acquiring hepatitis C, B or HIV. The harm associated with injection can be reduced by advising about poor injecting technique, providing clean needles and syringes, and by giving correct advice on cleaning injecting equipment. Most significantly, the sharing of needles, syringes and injection equipment (spoons, filters, water) needs to be clearly addressed with the client. Many drug misusers only consider sharing to be the joint use of the needle or syringe and have not considered that water used for preparation and disposal, and other injecting paraphernalia such as filters, can also run significant contamination risks, and possibly play a significant role in the transmission not only of HIV, but also of the hepatitis B and C viruses. Many IDUs, as well as non-IDUs, will benefit from the provision of social services such as food, washing and bathing facilities and haircutting. Information and advice on safer injecting can be provided as follows: Always inject with the blood flow; rotate injection sites; use sterile new injecting equipment, with the smallest-bore needle possible; avoid neck, groin, breast, feet and hand veins; mix powders with sterile water and filter solution before injecting; always dispose of equipment safely (either in a bin provided or by placing the needle inside the syringe and placing both inside a drinks can); avoid injecting into infected areas; do not inject into swollen limbs, even if the veins appear to be distended; poor veins indicate a poor technique, so try to see what is going wrong; do not inject on your own; learn basic principles of first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in order that you may help friends at times of crisis. Appendix 2 : Stages of Change and relevant interventions Clinical management and treatment must be considered in the context of the natural history of drug misuse. Awareness of the different stages drug users pass through can help treatment staff 9 make the right responses. For example, the needs of a young person under 20 years, newly involved in drug misuse, are very different when compared with an individual who has been injecting drugs for over 10 years. The stages of change model described by Prochaska and DiClemente, linked to the technique of motivational interviewing, has important practical applications for assessment and treatment. Motivation is considered to be a pre-condition for effective treatment and this model assists treatment staff to encourage motivation in a more effective way. The model recognises that established drug users often only actively engage in change, or treatment for change, when they have passed through various key stages, as follows (possible interventions are listed in italics after each stage, although these are not exhaustive : 1. Pre-contemplation: A stage where drug users are not aware that they have a problem, and therefore do not seriously think about change. It is others, like family members, who recognise that there are problems and that change is required. Needle and syringe access and disposal programmes Harm reduction clinics Targeted health promotion Substitute prescribing (maintenance) Outreach Information and advice Social welfare services 2. Contemplation: A stage where the individual begins to weigh up the costs and benefits of their drug misuse; they feel ambivalent about their behaviour. The person considers that there might be a problem and that change might be necessary. (All interventions in 1. above) Motivational interviewing Structured counseling Preparation for detoxification Groupwork 3. Decision: A hypothetical stage where the balance of change is influenced and a point is reached where a decision is made to do something, or possibly nothing, about their drug-using behaviour. 4. Action: The process or stage of doing something. The person chooses a strategy for change and pursues it, taking steps to put their decision into effect. This is traditionally where ‘motivation’ for treatment would begin and treatment staff would have a significant role to play. (All interventions listed in 1 and 2 above may be appropriate) Structured daycare In-patient detoxification Community/home-based detoxification Reduction prescribing 5. Maintenance: During this stage the task is to maintain the gains that have been made in order to avoid a return to undesired previous behaviours. Failure to consolidate progress may result in a 10 relapse. This is where relapse prevention services play a significant part in determining whether a person returns to drugs or not. Residential rehabilitation Skills-based services Social welfare services Vocational training/income generation opportunities Support groups Relapse prevention Family therapy 6. Relapse: At the point of relapse, the individual will return to previous patterns of behaviour at either a pre-contemplative, or contemplative stage. However, relapse in itself would not be considered a treatment failure but a positive learning experience, potentially increasing the successful outcome next time round and complete abstinence from drug use. It is necessary to distinguish between a lapse and a relapse, either can be viewed as a positive learning experience for some drug users. All the above interventions may be appropriate i) Pre-contemplation may last for years but staff and services can encourage the move to the contemplation stage, e.g. by using specific forms of motivational interviewing and providing basic harm reduction advice. Contemplators also need encouragement to make a decision and enter the action phase of treatment, such as detoxification or regular attendance at a treatment centre. Maintaining the positive effect of treatment involves structured and active follow-up and aftercare services to build on changes already made. This can take months or even years. ii) The model highlights that at each stage of treatment and change, drug users may relapse and return to previous phases. It is common for many drug users to relapse one or more times before finally stopping drug use altogether. iii) The value of this model is that it assists in clarifying which stage the individual drug misuser is at and this informs the treatment response. It follows that treatment interventions must be tailored for particular stages and needs in a drug user’s life. For example, there is no strong clinical indication to offer a substitute opioid drug or a package of detoxification to a drug misuser at the stage of pre-contemplation. However, there is a clinical responsibility to encourage the client to begin to contemplate his problem at that stage, so pre-treatment motivational counseling can begin.. Appendix 3: Relapse prevention A number of behavioural techniques have been developed to prevent relapse. Typically, these involve the identification of high-risk situations, where there is an increased likelihood of drug taking behaviour starting again. Rehabilitation and therapeutic communities are treatments aimed at developing specific changes in lifestyle to remain drug free in an environment where drugs are easily available. Self-help groups, such as NA, ex-addicts groups or those run through Mosques, can aim to help drug-dependent or drug taking individuals become abstinent. An important component of NA programmes is the adoption of limited objectives. The individual is advised to promise him/herself not to use drugs for just one day, something that many have done willingly or unwillingly in the past and therefore know to be possible. Having abstained for one day, the individual renews this short achievable contract with themself. If a day is too long, then the time 11 can be shortened to just 10 minutes at a time. This strategy focuses the person’s mind on the immediate problem of not taking drugs and undermines practised excuses and the rationalisation for drug taking. Note that Naltrexone-assisted relapse prevention should only be initiated by specialists experienced in this technique. References: Drug Misuse and Dependence – Guidelines on Clinical Management, 1999, Department of Health, UK Contemporary Drug Abuse Treatment – A Review of the Evidence Base, 2002, UNODC, Vienna Drug abuse treatment and rehabilitation – a practical planning and implementation guide, 1993, UNODC, Vienna Manual for reducing drug-related harm in Asia, 2002, McFarlane Burnett Institute for Medical Research, Centre for Harm Reduction, Australia Harm Reduction: Tackling drug use and HIV in the developing world, 2005, Department for International Development, HM Government, London T.T.Ranganathan, 2004, Addiction Treatment: an overview, Clinical Research Foundation, Chennai, India Andrew Shephard, 1990, Substance Dependency: A Professional Guide, Birmingham, Venture Press Ltd. Andrew Tyler, 1995, Street Drugs, London, Hodder and Stoughton National Drug Treatment Guidelines for Afghanistan_22_02_2006 12