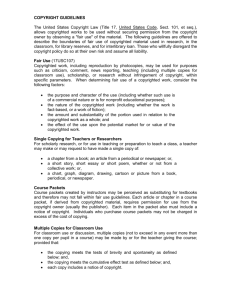

COPYRIGHT AS TRADE REGULATION

advertisement