Chapter 4: Focus Group Discussion Method

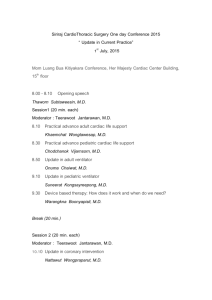

advertisement

CHAPTER FOUR FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION METHOD This chapter describes the Focus Group Discussion (FGD) method and indicates how it can be used to collect information in drug use studies. It begins with a brief overview of the method and the areas in which it can be used to study drug use problems. The major part of the chapter is devoted to the main steps involved in conducting focus groups. 4.10. Overview 4.11. What Is A Focus Group Discussion? A focus group discussion (FGD) is an in-depth field method that brings together a small homogeneous group (usually six to twelve persons) to discuss topics on a study agenda. The purpose of this discussion is to use the social dynamics of the group, with the help of a moderator/ facilitator, to stimulate participants to reveal underlying opinions, attitudes, and reasons for their behaviour. In short, a well-facilitated group can be helpful in finding out the "hows" and "whys" of human behavior. The technique is borrowed from social marketing where it was used to ascertain consumer satisfaction. The discussion is conducted in a relaxed atmosphere to enable participants to express themselves without any personal inhibitions. Participants usually share a common characteristic such as age, sex, or socio-economic status that defines them as a member of a target subgroup. This encourages a group to speak more freely about the subject without fear of being judged by others thought to be superior. The discussion is led by a trained moderator/facilitator (preferably experienced), assisted by an observer who takes notes and arranges any tape recording. The moderator uses a prepared guide to ask very general questions of the group. Usually more than one group session is needed to assure good coverage of responses to a set of topics. Each session usually lasts between one and two hours but ideally 60 to 90 minutes. 4.12. Use of FGDs in Drug Use Studies The method can be used in drug use studies in several ways. The following gives some ideas of ways to apply FGDs in the field. 4-1 a. Explore a topic about which little is known. For example, to begin the process of understanding cultural meanings of drugs in a community. b. Generate research questions if employed at the early stages of a multi-method study. c. Develop appropriate language to be used in a questionnaire. d. Complement other data in explaining people's actual thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and perceptions obtained from other methods. e. Develop appropriate materials and messages for educational interventions. 4.20. Key Steps in Conducting Focus Group Discussions (FGD) The steps in using FGDs to study a drug use problem are summarized below, followed by detailed discussion of each step. The extent to which these steps must be followed varies, however, depending on the training and experience of those involved in the data collection. 4-2 TABLE 4.1: Key Steps in Conducting a FGD Step 1: Plan the entire FGD study Step 2: Decide what types of groups are needed Step 3: Select moderator and field team Step 4: Develop facilitator's guide and format for recording responses Step 5: Train field team and pretest instruments Step 6: Prepare for individual FGDs Step 7: Step 8: 4.21. Conduct FGDs Analyze and interpret FGD results STEP 1: Plan the Entire FGD Study Once the decision to use focus group method is made, you will need to plan how to carry out the study. Planning is critical because it is the area where major decisions regarding the study are made. a. What Activities Need to be Planned? Planning decisions will involve the study design, selection and training of field team, collection of data, analysis, and report writing as well as planning for interventions. Other essential supporting materials and logistics such as an office for meetings by the field team, equipment for data processing, and transport and incentives for the field team must also be planned. b. Is There Need for a Resource Person? One important decision is to determine whether a resource person is needed to assist in planning and implementing subsequent stages of the study. This decision will depend on a number of factors. These include the size of the project, the resources available to you and your own experience with focus groups. If you are not quite confident with the method or the study is large, relying on a resource person to assist at this stage can help to ensure that subsequent stages of your study proceed smoothly. Otherwise, the services of a colleague familiar with FGDs could be all that you need. 4-3 c. Role of Resource Person in Training Field Staff One of the principal roles of the resource person is training of the FGD Moderators and assistants. If the field staff have no experience in applying the technique and have been involved in only clinical aspects of health, they will need considerable training. On the other hand, if staff have had some previous experience in similar studies, the task of the trainer is likely to be minimal. (See discussion of resource persons in chapter 2.) 4.22. STEP 2: Decide What Types of Groups Are Needed After developing an overall plan, you must decide the specific types of groups which will be used for your study. The following are some guiding principles: a. Identifying Target Groups Since broad generalizations are not usually made from the data obtained from FGDs alone, the common method for selecting participants for focus groups is by purposive (non-probability) sampling. An investigator selects those who, in his or her estimation, can provide the needed information. This depends on the target groups of concern to the study. For example, consider a study to determine the attitude of prescribers and mothers in public health facilities towards the use of antibiotics in the treatment of Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) in children. The two overall target groups will be prescribers in public health facilities and mothers who attend these clinics with their children. In selecting prescribers for a focus group discussion the study coordinator may decide to talk to prescribers working in hospital outpatient departments and health centers in separate sessions, if differences in their training or work setting might have an effect on their attitudes or behavior. This will be an example of quota sampling. On the other hand, in recruiting mothers for a similar discussion he/she may decide to draw participants from mothers in one or a few villages rather than from many villages in the district. This is a typical case of convenience sampling and, as its name implies, it is more convenient than a random sample of mothers drawn from all villages. Mothers may be further grouped into those living in villages near the district hospital and those living in remote villages, if ease of access is seen as an important determinant of behavior. When selecting participants, target those population segments likely to provide the most meaningful information, especially where differences might affect the way you design an intervention. Nevertheless, be sure that the group is representative of the larger population, though this does not imply that the results can be generalized. b. Composition of Groups Recruiting participants can require a great deal of effort if you need specific target groups. There are no rigid rules to follow, but one of the guiding principles in forming groups is that participants 4-4 should have something to say about the topic of concern, and they should feel comfortable saying it to one another. For example, a group that includes both para-medics and health center officers-incharge might not be very successful since the para-medics might be reluctant to speak in the presence of their "superiors." Forming two groups, one with para-medics and one with officers-in-charge, would more likely generate more free and open discussion. In order to separate participants into groups a screening process is sometimes required. This involves using a predetermined list and a very short questionnaire to select those who qualify and are interested in participating. Qualifying questions may include demographic characteristics, personality factors, or other variables related to the purpose of the study. Table 4.2 is an example of a screening questionnaire used in a study of family planning in Ghana. 4-5 Table 4.2: Example of a Screening Questionnaire 1. Do you have any children? Yes ............................. No ................................ Reject ............................... 2. Name: .......................................................................... 3. Age: ................................ 4. Number of children: ................ 5. Number of boys: ............. 6. Number of girls: ............... 7. Marital Status: ............................................................................................................................ 8. Educational level: ....................................................................................................................... 9. Occupation: ................................................................................................................................. 10. Religion: ...................................................................................................................................... 11. Number of years of residence in village/town: ......................................................................... 12. Do you practice family planning?: ............................................................................................ 13. What contraceptive do you use?: ............................................................................................... Selecting the Group and Conducting the Sessions A screening form was used in selecting participants for contraceptive user or non-user groups. A woman qualified if she had at least one child. For the user group, the women were, in addition: (a) Married, single, or divorced (b) current users of any modern contraceptive (c) resident in the village for a considerable length of time. Women for non-user groups had the same characteristics as the users except that they had either never used contraceptives or were not using them at present. c. Number of Groups 4-6 Practically, the number of focus groups you conduct will depend on the purpose of the study. Thus, more sessions may be needed, for example, to explore the reasons for the use of antibiotics in the treatment of ARI, in contrast to a simpler exploratory goal of discovering the terms people use to refer to antibiotics for the purpose of designing a questionnaire. 4-7 In general, however, the more similar the study population in terms of social characteristics, the fewer groups that will be needed. If there are several distinct target subgroups in the study population, you should run separate FGDs for each, e.g., groups composed entirely of doctors run separately from those of pharmacists, or groups with men run separately from those with women. One useful strategy is to conduct as many FGDs as are necessary to provide an adequate answer to the study questions. A minimum of two FGDs should be planned with each target subgroup. After these two sessions with each subgroup, if results are consistent, there may not be a need for any more FGDs in this subgroup. However, if important inconsistencies emerge, additional FGDs should be conducted until the reasons for the inconsistencies are explained. One focus group discussion for any meaningful topic in a particular target group is certainly never enough. d. Group Size Practically, the size of the group should facilitate a dynamic interaction between the participants. Having a too small or too large group would make this difficult. The best size is at least six members, but not more than twelve. Groups of less than four or more than twelve are difficult to manage, and the benefits of group dynamics that make FGDs effective are usually lost. e. Contacting and Informing Participants The initial contacting of participants may occur by mail, telephone, or in person. Personal contact may be the most feasible way in most developing countries. Recruiting can be done at a clinic, the market, or by going from house to house in the community. When you enter a community or institution to recruit, it is advisable to contact the head of the community, or the person in charge of the institution, to obtain permission. These people can help you with vital information about particular cultural practices and habits of the local population or community, as well as identifying participants who meet the target criteria.. Provide prospective participants with information about the study but restrict this to a general description, including the fact that it will involve a group discussion. If any form of incentive is to be provided, such as refreshments or transport, this should be indicated along with when and how it will be provided. Invited participants should be notified a few days before the discussion. 4.23. STEP 3: Select Moderator and Field Team The selection of the personnel who will be involved in the study is essential since the success of FGDs depends on the calibre of staff. a. Field Staff Requirements The usual staff requirements for focus group discussion are: 4-8 1. A Moderator/Facilitator who has a very demanding role as the discussion leader of the group. This involves the following: ! directing the discussion and not taking over the group; ! encouraging participants to express their feelings and opinions and communicate among themselves during the discussion; ! building rapport to gain the confidence and trust of the participants and thereby probe beneath the surface of comments and responses; ! maintaining flexibility and being as neutral as possible: if the discussion wanders away from the topic, he or she subtly directs it back without offending participants; ! controlling the time allotted to each topic and to the entire discussion. In view of the high leadership and communication skills required of FGD moderators, you need to select them carefully. Generally, educational background such as sociology, mass communication, or psychology, as well as experience in moderating focus groups, are useful. These requirements are, however, not essential, nor are they enough. The key qualification is an appropriate personality, since the procedures for moderating a group can be learned during training. Key personality traits include: sensitivity, willingness to listen, tolerance for different views, ability to focus a discussion, and assertiveness in supporting as well as cutting off the expression of opinions. Experience has shown that nurses, teachers, community leaders among others have proved very skillful as moderators. 2. An Observer/Recorder is also present, mainly to observe the session and take notes. The observer/recorder is responsible for the use and care of any tape recorder or other equipment. It is good to have the note taker trained in how to be objective in recording discussions and observing non-verbal expressions. Participants must be informed of the presence and role of the observer at the beginning of the session. He or she should be seated away from the group. Even though the observer/recorder is not expected to take part in the discussion, he or she may do so in a few exceptional cases, for example: ! if the moderator overlooks a useful point raised by a participant; ! to suggest a new question or topic relevant to the study; ! if the moderator has missed a an important topic in the guide. 4-9 3. Other Staff Depending on need, other staff may sometimes be recruited to assist in running the discussion, but they do not necessarily constitute part of the group. 4.24. ! Assistants: useful for sessions where interference from crowds and children has to be controlled. ! Translators: sometimes necessary where the moderator is not fluent in a local language. STEP 4: Develop Moderator's Guide and Format for Recording Responses The main purpose of the guide is to provide direction for the group discussion. To ensure that all related issues are covered in the study, it is recommended that all parties involved in the study have an input or consult in its preparation. a. Structure and Sequence of Topics Discussion guides will differ depending upon the topic under investigation and the target populations (e.g., physicians, pharmacists, mothers of children under five). Nevertheless, the general categories of questions in a guide for focus group discussions include: b. ! General questions which are designed to open the discussion and to allow participants to reveal common perceptions and attitudes. The sequence of questions on a given topic should proceed from the general to the specific. ! Specific questions designed to reveal key information and show the feelings and attitudes of participants. ! Probe questions designed to reveal more in-depth information or to clarify earlier statements or responses. Wording of Guide Questions in FGDs are generally less structured in order to elicit flexible response. The guide must be phrased in simple language. Avoid long and complex statements and make sure that the meanings are clear. Do not word questions to make people feel guilty or embarrassed. For example, instead of asking: "Why don't you go to the health center when your child has a serious cough?," the same question might be phrased: "What do you think might happen if you go to the health center when your child has a cough?@ 4-10 The questions must be framed in an "open-ended" style to enable participants to respond freely. Example (to prescribers at health centers): "How do you feel about treating cough with antibiotics?" This question allows respondents to discuss their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with antibiotics. It does not, however, place a judgment on antibiotic treatment, limit them to any specific antibiotic, nor indicate what other drugs may be used in addition to antibiotics. Questions should never imply what is acceptable and what is not. Suppose you are interested in knowing what other drugs are combined with antibiotics in the treatment of cough. This will require a question to encourage participants to speak about a range of other drugs. You would not want to ask a question like: Bad Example: ADo you think drugs besides antibiotics are needed for cough?@ This question can be answered yes or no, and it also suggests that other drugs are not needed, and participants may be reluctant to talk about what they actually do. It would be better to ask: Example: AI would like us to talk about drugs that are used for cough. Can you tell me about some of the drugs that are commonly used?@ This questions allows the respondents to answer in any way they choose, but it also suggests to them that there is a range of drugs that can be used for cough. It is important to avoid questions that have a yes/no answer. Occasionally it is possible to get a quick "Yes" or "No" answer which can then be further explored, but generally it is not a good way of questioning since such answers do not encourage lively discussion. c. Number of Topics Most FGD guides consist of fewer than a dozen topics, though the moderator may frequently probe responses and add new topics as the actual interview progresses. It is recommended that the guide be written with just one hour in mind to allow time for additions to be made in the field. Table 4.3. is an example of a list of questions in an FGD Guide on the overuse of antibiotics in the treatment of cough (ARI). 4-11 Table 4.3: Example of FGD Guide on Overuse of Antibiotics in Treatment of Cough 1. Introduction [Narrative welcoming participants, describing reasons for discussion, and setting up the general ground rules for the session] Ground Rules 1. 60-90 minutes (tape recorded -- observer and note taker) 2. Speak clearly/one at a time 3. Conversation/all participate 4. No right/wrong answers 5. Assurance of anonymity and confidentiality 2. Diagnosis Can we talk about when your child gets a cough (ARI)? In your own experience, how do doctors find out what is wrong with the child at these times? Probe: Do they depend mostly on symptoms or lab tests? What are some of the tests for? What are the common reasons for cough? 3. Treatment of Cough Let us talk now about the treatment of cough at the health centers. Can you tell me the common drugs that are prescribed for cough at the health centers? 4. Patient Expectation I would like to know more about how you feel about the treatment your child receives for cough. Do you usually come to the health centers with any expectations about the treatment you will receive? Probe: Do you prefer certain kinds of treatment? What do you do if your expectations are not met? Do you try to convince doctors to give you the treatment you prefer? 5. Attitude towards Antibiotics Can you tell me something about how you feel about antibiotics as a treatment for cough? Probe: Do you know the names of specific antibiotics that you think are good? Do you prefer pills or injections? Do they use other remedies/drugs for treating cough? What are some of these? Why do you use these remedies/drugs? 4-12 4.25. STEP 5: Train Field Team and Conduct Pilot Test The field team's ability to perform well depends on their previous experience, and on how they are trained for a particular study. Training is a very important part in ensuring the success of the study. a. Training Hints Before you begin the training, you need to make sufficient preparations to ensure that all aspects are covered and everything proceeds smoothly. The following are useful hints to assist in the training. ! Choose a comfortable location for the training. ! Keep all training sessions as simple as possible. ! Use simple language: complex language may make the tasks and concepts difficult to understand. ! Allow regular practice through role plays in order for team members to gain confidence in their abilities. ! Allow sufficient time for field practice or rehearsals. b. Training Package 1 Theory Sessions Depending upon previous experience of the field team with focus groups, the training package should involve several or all of the following theory sessions: ! ! ! Introduction to Focus Groups ! What are focus groups? ! How helpful are focus groups in drug use studies? What information will we be collecting? ! What specific drug use problem(s) are we investigating? ! What are the objectives and rationale for the study? Preparing for the Individual FGDs ! Becoming familiar with the FGD guide 4-13 ! ! ! 2. Reason for role plays Conducting the FGD ! Roles of the field team members ! Activities before the session: pre-arrangements and visits; checklist for FGD ! Activities during the session: reception/refreshment; opening the meeting/introduction; conducting and recording the session/group dynamic tips; closing. ! Activities after the session: field debriefing; office debriefing; transcribing and expanding field notes. Analysis and report writing of FGD results: ! Data analysis: Individual session reports; combined analysis. ! Report writing Practice Sessions Role playing involves a mock discussion in which members of the field team assume roles as moderator, observer and participants as a way of practicing the technique. While the session is going on, other members of the field team observe and give their objective feedback after the role play. More than one trial should be held with field team members while changing roles each time. Pilot testing is essential because it provides: c. ! an opportunity to determine if the wording in the guide is appropriate for eliciting discussion, i.e., whether it is understood as intended; ! a way of checking the effectiveness of training of field team members; ! much needed field practice for the staff to develop confidence; ! a means to identify potential problems likely to be encountered in the actual study. On-going Revision of FGD Guide Results of pilot tests will provide more information or new insights that are important for the study and interesting to participants. Each new focus group may lead to changes in the guide. In consultation with moderator(s) and other study investigators, the field coordinator should be able to modify the guide while the study is in progress. 4-14 4.2.6. STEP 6: Prepare for the Individual FGDs Between training field staff and starting the actual field work, an important link is preparing for the individual FGDs. This includes the following: a. Site Selection and Location for FGD Visit the project site(s) together with the field team and locate a place for the group meeting some days before the scheduled time. This will enable you to familiarize yourself with available logistics. The site for the discussion must be easily accessible to participants and convenient to the field team. The selected site must also be neutral (usually not a health facility) and large enough to accommodate all the participants and the field team. b. Date and Time For most focus groups in communities the ideal time is evening, while for those involving health staff late afternoon is often the best time, when the daily office routine is over. Make a time table that will guide how you will proceed with the field work after deciding the site(s), day(s), and time(s). See an example of a project time table in the annex. c. FGD Checklist Ensure that all equipment is ready before the field work. A checklist may include the following: (a) Arrange Transport Chairs, Mats, etc. Refreshments Other incentives, if any (b) Bring to the Field Tape Recorder Microphone (if needed) 3 blank 60 minute cassettes Batteries (plus extra) Moderator's guide Recording forms Test all recording materials a day before you go to the field to ensure that they are in working condition. 4.27. STEP 7: Conduct the FGD The climax of all the preparations made for the study is the actual FGD. On the day of the discussion a host, usually the moderator, and other members of the field team should be present at the venue before participants arrive. Snacks or drinks may be served to welcome the participants and put them at ease. 4-15 a. Conducting the Discussion In general, the session proceeds in the following main stages: ! Introduction; ! Warm-up; ! Discussion; ! Wrap-Up/Summary. 1. Introduction The moderator's brief introduction is aimed at making respondents relaxed, initiating rapport, and establishing the "ground rules" for the discussion to follow. In it the moderator: 2. ! speaks in a casual, friendly manner to help respondents relax; ! introduces himself/herself by giving his/her name and sometimes providing information about himself/herself; ! explains the general purpose of the group meeting to foster group feeling; ! encourages respondents to feel free to give their frank and honest opinions, explaining that there are no right or wrong answers, and it is okay to have feelings different from others; ! establishes neutrality by assuring respondents that he/she (moderator) has no connection with the subject of discussion that will affect his/her feelings; ! gives respondents the group rules: speak clearly and one at a time, avoid interrupting one another, and allow all participants a chance to speak; ! explains the purpose of any recording equipment that is being used; ! assures the group of confidentiality. Warm-Up This stage includes self introductions by respondents. They are asked to give their names and other information about themselves, for example mothers may give age and numbers of children. The moderator must show interest in what participants have to say, for example, by making eye contact and attending to each introduction. The moderator must sometimes probe for clarity and 4-16 understanding of information. He or she must also confine discussion only to the introductory formalities to avoid digressions. 3. Discussion This part begins the actual discussion of the study topic. At this stage efforts are directed at understanding the issues surrounding each topic. The moderator's role at this phase is very demanding. The following are some strategies the moderator can use to generate a healthy discussion: 4. ! Maintain a friendly and warm attitude to make participants feel comfortable. ! Do not behave like an expert. ! Build rapport by showing sensitivity to the needs and feelings of participants. ! Pretend to convey a lack of complete understanding sometimes with statements such as: "I didn't know that. Can you tell me more about it?" ! Pause when necessary to allow participants to think more or provide additional information. It is helpful to use incomplete statements like: "I don't know, maybe in some cases .... and wait for response. ! Use in-depth probes to clarify responses given by a participant, for example by asking: "Could you explain further?" or "I don't understand ... " or by repeating the response as a question: "...It's effective?" ! Know when to keep quiet and use it to your advantage, and do not let quietness intimidate you. ! Encourage participants to communicate among themselves. Wrap-Up Summary The last five to ten minutes of the session consists mainly of summarizing and recapping the identifying themes of the group. This is meant to assist the moderator, the recorder, and the respondents in understanding what has occurred during the session. It also provides an opportunity for respondents to alter or clarify their positions or add any remaining thoughts they may have. The steps involved may be ordered as follows: ! Inform participants that the meeting is closing and ask for any comments; relevant ones could be explored in depth. 4-17 ! Thank the participants and acknowledge that their ideas have been valuable and will be utilized. ! Serve refreshments and listen for additional comments as the group breaks up. ! Provide participants with any information they need but do not feel obliged to comment on everything that everyone says. The moderator and recorder need to meet to review and complete their notes after the session, and to evaluate the success of the discussion. b. Debriefing It is important to hold regular debriefing sessions between the investigator(s) and field team to discuss progress. In cases where the investigator accompanies the field team to the field, a short field debrief lasting about fifteen minutes, can be held immediately after the field session. It should be limited to issues that might be forgotten by the time a full debriefing session is held. A full debriefing takes place with the entire study team. The session can be used to assess whether the discussions are providing the information required to meet the study objectives. If not, necessary changes may be made in the guide and approach. It is advisable to prepare a meeting agenda to "guide" the debriefing session. c. Recording and Managing Information in FGDs 1. Note-taking The simplest way to record information in FGDs is note-taking by the observer. It is not essential for the person to have shorthand skills for this task, but practice in note-taking during pilot testing will be helpful. Other non-verbal feedback such as tone of voice, laughter, or posture should be noted, as these may suggest attitudes useful for the report. The observer must not inject personal judgments when recording notes. Comment should be put in brackets. Similarly, direct quotes from participants should be marked with quotation marks. After the session, the observer should go back over the notes to add any further detail. (Figure 4.1 is an example of the structure of an FGD observer's notebook.) 4-18 Figure 4.1: Format of Contents of Observers's Notes The recorder's notes would usually include the following: 1. Group: (Identification of participating group) 2. Date: (of group) 3. Time: (group began and ended) 4. Name of Community/Group of Professionals: (brief description of it and any other information that may bear on the activities of the participants (e.g., distance from next town, conditions of health services)) 5. Meeting Place: (location and brief description (i.e., big, convenient) and how this could affect the discussion) 6. Participants: (including number and personal characteristics and other kinds of relevant information such as presence of children) 7. Group Dynamics: (general description, level of participation, dormant participants, interest level, boredom, anxiety, etc.) 8. Interruptions: (occuring during the session) 9. Impressions and Observations 10. Seating Diagram of the group. (It is best to have the group seated in a circle.) 11. Running Notes on discussion of various topics. 4-19 2. Cassette Recordings Since taking accurate notes on an entire discussion can be difficult, it is ideal if a tape recorder can be used. Though transcribing tapes is not easy, tapes also serve as permanent records of the FGD and can be listened to many times to clear up any doubts or confusion. They also make it easy for an investigator to assess the performance of the field team. The tape recorder must not, however, be allowed to interfere with a discussion. Asking participants to speak into the tape recorder, for instance, may disrupt the FGD dynamics as the microphone is passed. After the session, all tapes used must be transcribed and edited for analysis. 3. Video Recording Video is mainly used in developed countries. If a video camera is available, it may be used with discretion depending upon how much experience your group has had with such technology. Video recording provides a record of both what participants say and how they say it. CARTOON-PROVIDE A SKETCH CAPTIONED What happened to group dynamics at this discussion? 4.28. STEP 8: Analyze and Interpret FGD Results Focus group analysis is a process that begins when you enter the field and continues until completion of the final report. This continuous process avoids the situation of accumulating a mass of data that may be difficult to cope with at the end of a study. Since the moderator and the observer/recorder are the key actors in gathering the information the investigator should work closely with them in analyzing the data. a. How much Analysis is Required? The amount of analysis required in any focus group study will vary with the purpose of the study, its design, and the extent to which conclusions can be drawn from the data available. A simple analysis using notes/feedback material of the field team may suffice in exploratory studies where the conclusions of the study are straightforward. In general, however, analysis of focus groups involves various activities, each of which is important for producing the final report. These include: 4-20 1. Field Notes and Debriefings [Refer to the in-depth interview analysis] Field notes include written notes and comments on both verbal and non-verbal exchanges during the FGD compiled by the moderator and the observer. Debriefing notes compiled immediately after the sessions afford a quick and easy way of summarizing the data while the events of the FGD are still clearly in the minds of the field staff (see Step 7 above). Taken together, the field notes and debriefings can give a snapshot of the key findings from each session. 2. Session Summaries Within a day or two after the completion of each FGD, the moderator should complete a session summary. Working with his/her field notes and notes from the field debriefing (if completed) the moderator should prepare a 2-3 page summary of the session covering the following: 3. ! number and type of participants ! place and length of session ! moderator=s evaluation of how successful the session was in achieving meaningful interactions among all participants and staying focused ! key findings from the session for each of the major topics in the moderator=s guide, including useful non-verbal information ! unexpected findings and insights, especially regarding factors that may increase or decrease the success of the intervention. Transcripts Transcribing is very demanding. It is therefore recommended that transcript analysis be carried out as soon as the transcripts become available and not when all the focus groups are completed. The following guidelines may be followed for analysis of transcripts: ! First, read through the transcripts with the study questions in mind; note any impressions and major opinions from the discussion. ! Second, read the transcripts again, this time looking at each specific topic of interest or importance defined in the moderator=s guide. Also note any new areas of interest raised in the session. ! Third, read through each transcript again and strike out any responses that might have been forced on participants through poor moderating. Also, you may remove sections that have been poorly transcribed or that do not make sense. 4-21 ! Begin a coding process by marking the transcripts according to various sub-topics or areas of interest to indicate what participants are talking about. For instance, in analysing data concerning the use of antibiotics in the treatment of ARI, every time a participant mentions antibiotic use, you can mark the section to indicate this by saying ANTIBU (ANTIBIOTIC USE). At the end of each page, therefore, your transcripts will have various code words running down the side. This makes it easier for you to identify areas of interest. Prepare as many code words as necessary to meet your information needs, but try to keep these simple and short. Note also that not all responses will fall into the neat categories of information that you hope to obtain. If you come across a new response that introduces a new idea or topic of importance, code it. You may need a code book for the exercise. ! 4. The final task of the analysis involves using the list of information required to check what information you have actually obtained. This will tell you whether the objectives of your study are being met or not. Alter your question guide for the next session if you are not getting close. Log Book Some studies use a log book to organize the transcribed analysis. It consists of a table that enables the investigator to record the responses according to selected topics of interest. The idea behind the log book is to retain the full range of responses in order to be able to spot relevant issues. Topics of interest are written on the left column of the page while the right side is divided into columns for the various FGD sessions. Responses are then tallied under each column as and where they occur according to sub themes. Approaching the analysis this way enables the investigator to find out how many times an issue was discussed across all the focus groups, as well as how many times a response was given. The approach is very useful when combining FGD results from different discussion groups. (i.e., prescribers, paramedics, patients, etc.). This approach is similar to the process of synthesis across methods. (See Chapter Seven.) An example of a log book for a study on the overuse of antibiotics is provided in Table 4.4. 4-22 Table 4.4: Example of Log Book on Use of Antibiotics Reasons for Preferring Antibiotics Topic # of Mentions of Issue by Session # of participants 3 41 52 6 Pressure from families and peers Prevention against pneumonia Appropriate treatment for cold and coughs Better/more powerful drugs Complaints/requests from patients Fear of losing patients Severity of symptoms a Writing the Report If you have used all the methods mentioned so far, the following may be available to you for your report writing: log book, codes from transcripts, session summaries, field notes, and debriefing notes. Your task in report writing involves deciding which responses are important to include in the report and which can be omitted. Findings are presented according to topics or issues of interest. Use quotations to illustrate strongly expressed thoughts, beliefs, and emotions by the participants. Remember to describe the overall consensus of the groups by sub-topics in the moderator's guide. Majority and minority feelings, as well as apparent differences in feelings by characteristics of respondents (e.g., sex and age) should be distinguished. Your final report must therefore reflect the 4-23 variety of participants' ways of thinking about the subject of study. Many focus group reports do not indicate how many participants discussed a certain issue. The common style is to say: "The majority of participants said ... " or "Few of them, however, felt....." Depending upon the purpose of the research, such presentations can be sufficient and useful. Nevertheless, it is sometimes useful to dwell a bit on frequency of occurrence of particular issues. b. Interpretation of Findings Interpretation involves explaining your findings in terms of the problem or question you want to answer. In the course of the study, you may have developed some ideas about what the respondents are saying. This is the time to question yourself about how significant the information you have gathered is to the problem under investigation. As much as possible involve the rest of the team, particularly the moderators and observers in this exercise since they had a direct contact with the groups. Based on the discussion of findings, the investigator may then be in a position to make useful recommendations for planning and developing an intervention. Any recommendations about how future studies should be conducted must also be noted. In general, the format of the focus group report should consist of: ! title of study ! objectives and methods, including data analysis ! major findings in line with significant broad topics of the moderator=s guide ! discussion ! conclusions ! recommendations for interventions. 4-24 CHAPTER SUMMARY Following is a summary of the main issues discussed in this chapter. FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION (FGD) METHOD IN DRUG USE STUDIES OVERVIEW What is Focus Group Discussion? Use of FGDs in Drug Use Studies KEY STEPS IN CONDUCTING FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSIONS STEP 1: Plan the entire FGD What activities need to be planned? Is there the need for a resource person Role of resource person in training field staff STEP 2: Decide what types of groups are needed Method of sampling (selection criteria) Composition of groups Number of groups Group size Contacting and informing participants STEP 3: Select moderator and field team Field staff requirements moderator observer/recorder other staff STEP 4: Develop moderator's guide and format for recording responses Structure and sequence of topics Wording of guide Number of topics Example of an FGD guide STEP 5: Train field team and conduct pilot test Training hints Training package theory sessions practice sessions On-going revision of FGD guide Prepare for the individual FGDs STEP 6: 4-25 Site selection and location for FGD Date and time Plan for supporting materials or FGD checklist STEP 7: Conduct the FGD Conducting the Discussion Introduction Warm-up Discussion Wrap-up summary Debriefing Collecting and managing information in FGD STEP 8: Analyze and interpret FGD results How much analysis is required? debriefing notes transcripts log book Writing the report Interpretation of findings Example of format of an FGD report List of Tables List of Figures List of Tables Table 4.1 Key Steps in Conducting FGD Table 4.2 Example of a Screening Questionnaire Table 4.3 Format of Contents of Observer's Notes Table 4.4 Example of a Log Book Table 4.5 A hypothetical example of an FGD report List of Figures Figure 4.1 Example of Format of a Focus Group Moderator's Guide 4-26