Ethics in Family Counseling

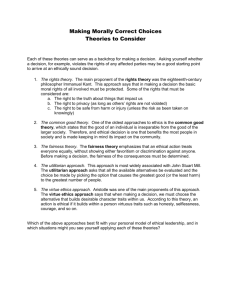

advertisement