5. Causes of the Great Vowel Shift

advertisement

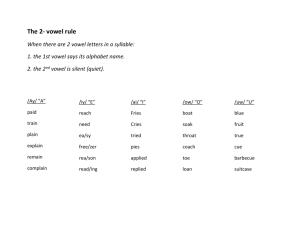

Course Project: The Great Vowel Shift LD 5332 Applied Phonology Spring 2003 Ed Kenschaft Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 2 of 20 Table of Contents 1. Synopsis ....................................................................................................... 3 2. Historical Background................................................................................. 3 3. Great Vowel Shift ......................................................................................... 4 3.1. Analysis 1: Baugh and Cable ............................................................................................................. 4 3.2. Analysis 2: Chomsky and Halle ......................................................................................................... 5 3.3. Other Analyses .................................................................................................................................... 7 3.4. Comparison of Analyses 1 & 2 .......................................................................................................... 7 3.4.1. Phonetic ........................................................................................................................................ 7 3.4.2. Theoretical .................................................................................................................................... 8 4. Synchronic Vowel Shift ............................................................................... 8 4.1. Giegerich ............................................................................................................................................. 8 4.2. Chomsky and Halle .......................................................................................................................... 13 4.3. Evaluation ......................................................................................................................................... 13 5. Causes of the Great Vowel Shift............................................................... 14 5.1. Pilch ................................................................................................................................................... 14 5.2. Diensberg ........................................................................................................................................... 15 5.3. Bertacca ............................................................................................................................................. 15 6. Various Ramifications of the Great Vowel Shift ...................................... 16 6.1. Effects on Spelling ............................................................................................................................ 16 6.2. Scottish Dialect ................................................................................................................................. 16 7. Further Research ....................................................................................... 17 7.1. Germanic Roots ................................................................................................................................ 17 7.2. Scottish .............................................................................................................................................. 17 7.3. Alternate Theories ............................................................................................................................ 18 8. Conclusions ............................................................................................... 18 9. References ................................................................................................. 19 LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 3 of 20 1. Synopsis One of the defining features distinguishing Modern English from Middle English was the Great Vowel Shift (GVS)1, which occurred gradually over the course of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (Baugh and Cable 235). Linguists differ in their analysis of the processes that occurred during the GVS, their causes and effects. We evaluate some of these analyses, focusing particularly on the theories of Baugh and Cable (1951) and Chomsky and Halle (1968). To understand the effects, we examine the correspondences between the diachronic GVS and synchronic vowel shift in Modern English. All phonetic transcriptions have been adapted to IPA notation.2 2. Historical Background The history of English is broken roughly into three main phases: Old English, spoken before the Norman invasion in the 11th century; Middle English, spoken between the 11th and 15th centuries; and Modern English, spoken from the 16th century onward. To speak of any of these phases as a monolithic language is a device of convenience, since in fact there were countless dialects spoken at any time, and considerable changes during each period. Nonetheless, the labels are useful for describing characteristics generally common to the dialects of a given phase. Old English was inflectionally rich. Middle English saw a complete transformation of inflectional patterns, leaving a language with “relatively few and simple inflections” 1 Also known as the Tudor Vowel Shift (Pilch 79). 2 Where the interpretation is subject to confusion, this is indicated in a footnote. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 4 of 20 (Moore 114). In comparison, the changes in sound qualities between Old and Middle English were relatively minor (Baugh and Cable 236). The inflectional changes between Middle English and Modern English were comparatively insignificant. Even so, Shakespeare (early Modern English), 200 years after Chaucer (Middle English), would have found his speech virtually incomprehensible, thanks to the GVS. In contrast, a modern speaker, 400 years after Shakespeare, would have little more difficulty understanding his pronunciation than we would in listening to a broad Irish brogue (Baugh and Cable 234-235). 3. Great Vowel Shift 3.1. Analysis 1: Baugh and Cable Baugh and Cable (238) provide the following analysis of the Great Vowel Shift. All the long3 vowels gradually came to be pronounced with a greater elevation of the tongue and closing of the mouth, so that those that could be raised ( 45) were raised, and those that could not without becoming consonantal () became diphthongs. The change can be visualized in the following diagram: 3 Baugh and Cable do not refer to the later generativist concept of tense vs. lax vowels, but rather restrict their discussion to vowel length. 4 From the diagram below, it is possible that this symbol is intended to represent the low front vowel . 5 Baugh and Cable represent this sound as either or . It is possible that is intended. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 5 of 20 Such a diagram must be taken as only a very rough indication of what happened, especially in the breaking of and into the diphthongs and . Nor must the changes indicated by the arrows be thought of as taking place successively, but rather as all part of a general movement with slight differences in the speed with which the results were accomplished. … [I]t is apparent that most of the long vowels had acquired at least by the sixteenth century (and probably earlier) approximately their present pronunciation. The most important development that has taken place since is the further raising of M.E. to . Baugh and Cable’s discussion assumes that each vowel represents an underlying phonological unit, and that the definitions of these units changed over time. The analysis is purely lexical and diachronic, making no appeal to synchronic phonological rules. Note the implication that the diphthongs came about only because there was no higher place for the high vowels to rise to. 3.2. Analysis 2: Chomsky and Halle Chomsky and Halle (178-243) provide a different analysis. They explain the GVS in terms of several synchronic rules which were introduced into the grammar of Modern English. Two of these rules are particularly significant: rule (1) which transforms all tense vowels into diphthongs; and rule (2) which shifts tense vowels.6 6 These are preliminary forms of these rules. The final forms are rather more complicated (243). LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 6 of 20 (1) Diphthongization voc cons high back round → tense back / __ (2) Vowel Shift tense V → high low _____ high low _____ low high (a) (b) These rules result in the following set of derivations. (3) Diphthongization phonological representation Vowel Shift (a) Vowel Shift (b) Chomsky and Halle describe the Vowel Shift Rule as “a synchronic residue of the Great Vowel Shift of Early Modern English” (184). Various other rules are described as “refinements and extensions of the Vowel Shift Rule” (188). Notable among these are rules converting / / to / /. Chomsky and Halle demonstrate in great detail how these changes occurred gradually, tracing several stages of vowel shift through the writings of contemporary linguists (259289). LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 7 of 20 3.3. Other Analyses It must be noted that the two theories summarized above do not exhaust the range of possible explanations for the changes observed in the vowels of the English language. One modern linguist argues that the theory of the Great Vowel Shift “fits squarely into patterns of thought & social bias characteristic of its era” (Giancarlo, abstract). Another article suggests that such theories “represent historiographic constructs, or stories, whose plausibility depends not only on their truth value but at least as much on their fruitfulness & on the consistencies they produce” (Schendl and Ritt, abstract). We do not dispute such claims. However, this paper limits its discussion to the two primary analyses outlined above, accepting them as genuine attempts to model the perceived facts. 3.4. Comparison of Analyses 1 & 2 3.4.1. Phonetic Perhaps the most striking disparity between the two analyses is in the perception of phonetic data. Chomsky and Halle assert “a well-known fact” that Modern English tense vowels are always diphthongized (183). Baugh and Cable, on the other hand, only observe diphthongs resulting from the shift of previously high vowels.7 It seems unlikely that the language changed dramatically between Baugh and Cable (1951) and Chomsky and Halle (1968). One can only speculate what may have led to the 7 As I scan the works of later writers, all seem to assume Baugh and Cable’s characterization, rather than Chomsky and Halle’s (e.g. Smith, abstract). LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 8 of 20 differing perceptions.8 Perhaps they spoke different dialects. Perhaps Baugh and Cable did not credit the subtle glide in Modern English clean (which they transcribe []) compared to the strong diphthong in five [].9 3.4.2. Theoretical The other major difference between the analyses is in the theoretical nature of the change. Baugh and Cable apparently considered the GVS to be purely lexical, a mass shift of the phonological representations of countless English words. According to Chomsky and Halle, on the other hand, the change did not affect phonological representations, but introduced new synchronic phonological rules. Which interpretation is preferable? To address this question, we must first take a closer look at some synchronic data. 4. Synchronic Vowel Shift To understand the Great Vowel Shift, it helps to look at vowel shift as it occurs synchronically in Modern English. 4.1. Giegerich Giegerich (305-309) discusses the following alternations: 8 One could presumably interview at least one of the authors – last I heard, Chomsky is still alive – but that would be beyond the scope of this paper. 9 Baugh and Cable’s work is primarily historical, not descriptive. They may not have been concerned with fine distinctions. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift (4) (5) The Great Vowel Shift Page 9 of 20 [] ↔ [] serene – serenity obscene – obscenity appeal – appellative metre – metrical deep – depth concave – concavity profane – profanity compare – comparative explain – explanatory sane – sanity [] ↔ [] In each set of examples, the vowel alternates between (in the terms of generative phonology) a tense [+tense] form and a lax [-tense] form. However, that does not fully describe the alternation. The tense form is also higher than the lax form, as in: [] (6) [+tense, +high, -low] [] [+tense, -high, -low] [] ↔ [-tense, -high, -low] [] ↔ [-tense, -high, +low] Giegerich provides two alternative analyses for these alternations. In the first analysis, the underlying vowel in (4) is // [+tense, -high, -low], and the underlying vowel in (5) is // [+tense, -high, +low]10. The lax form is produced through 10 Since IPA does not distinguish the open front unrounded vowel from the central equivalent, we use Giegerich’s symbol. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 10 of 20 a trisyllabic laxing rule (not further discussed here). The tense form is produced through a pair of rules that he calls Tense-Vowel Shift: (7) Analysis 1: Tense-Vowel Shift consonantal tense high low → consonantal tense high low → [-low] [+high (a) ] (b) Giegerich’s second analysis takes // as the underlying vowel in (4) and // as the underlying vowel in (5). The tense form is thus identical with the underlying vowel, and the lax form is produced by trisyllabic laxing and a pair of rules that he calls Lax-Vowel Shift: LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift (8) The Great Vowel Shift Page 11 of 20 Analysis 2: Lax-Vowel Shift consonantal tense high low → [+low] (a) consonantal tense high low → [-high] (b) Giegerich at first suggests that the Lax-Vowel Shift analysis is more plausible. His reason is that the surface form of one of the derivations is identical with the phonological representation, whereas the Tense-Vowel Shift analysis offers no such basic alternant.11 However, he then goes on to describe that in the alternation between Canada – Canadian, the same argument favors Tense-Vowel Shift over Lax-Vowel Shift. The simplicity argument does not clearly favor one analysis over the other. Giegerich ends his analysis with the decision unresolved. Earlier (294), Giegerich had provided data for other alternating pairs12: 11 Chomsky and Halle give several other examples of the reverse alternation (179). Kenstowicz demonstrates that a basic alternant does not always occur (104-110). 12 In (10) there is an additional alternation between [] and [], but we do not discuss this further. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift (9) The Great Vowel Shift [] ↔ [] divine – divinity derive – derivative line – linear (10) abound Page 12 of 20 [] ↔ [] – abundant profound – profundity denounce – denunciation In (9) and (10), the nucleus in the tense syllable is a diphthong. It is not obvious how the Lax-Vowel Shift analysis could be extended to this data, but it is quite clear how Tense-Vowel Shift could be extended. In fact, the Tense-Vowel Shift exhibits exactly the same behavior for tense vowels as we described diachronically for the Great Vowel Shift in Section 3. Giegerich raises the question whether these alternations should be considered phonological or morphological. He introduces several alternating pairs which do not fit the standard pattern, e.g.: [] ↔ [] (11) obese – obesity (12) confide – confession [] ↔ [] (13) clear – clarify [] ↔ [] (14) domain – dominion [] ↔ [] Clearly, the derivational rules must be lexical, since they have exceptions. Whether one is willing to posit phonological rules with lexical exceptions depends on one’s theoretical framework. If phonological rules are considered to be strictly regular, then the alternation must be considered morphological. (Giegerich 294-295) LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 13 of 20 4.2. Chomsky and Halle Giergerich was no doubt familiar with Chomsky and Halle’s discussion, but he does not follow their argument to its conclusion. They trace all the alternations described in (4), (5), (9), (10) to the set of rules described in Section 3.2. The synchronic alternations are precisely the effect of the Great Vowel Shift. Tense-Vowel Shift is thus a simplified form of their analysis. 4.3. Evaluation We have at least three alternative theories to describe the synchronic alternations in (4), (5), (9), (10). 1. With the Tense-Vowel Shift analysis, the phonological representations of both tense and lax vowels remain unaffected by the GVS, but synchronic phonological rules implement the effect. 2. With the Lax-Vowel Shift analysis, the underlying (i.e. lexical) phonological representations of both tense and lax vowels exhibit the effects of the GVS, and synchronic phonological rules reverse the effect for lax vowels. 3. With a morphological analysis, the GVS changed the phonological representation of the tense vowels, and left the short vowels alone, resulting in lexical morphemes with allomorphs bearing a surface similarity, but different phonological representations (and spellings). This can be summarized in table (15). LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift (15) The Great Vowel Shift Page 14 of 20 Theory Lexical shift Synchronic shift Tense-Vowel Shift none tense vowels only Lax-Vowel Shift tense and lax vowels lax vowels only morphological tense vowels only none The Tense-Vowel Shift analysis provides the simplest explanation with the greatest predictability. However, it must still allow for the possibility of lexical exceptions. We side with Chomsky and Halle, therefore, in asserting that the alternations are a direct result of the synchronic phonological rules introduced during the Great Vowel Shift, but that these derivations must occur at the lexical level. 5. Causes of the Great Vowel Shift The causes of the GVS are subject to as much debate as the nature of the shift itself. A brief discussion is merited. 5.1. Pilch Pilch (75-78) offers an explanation of the conditions leading to the Great Vowel Shift. His analysis suggests the same phonetic understanding as Baugh and Cable, as described in Section 3.1. Middle English did not have contrastive vowel length. Rather, vowel length was conditioned by syllable and word structure. However, there were eight long vowels and only five short vowels, with typically a two-to-two correspondence between them. For instance, long [] alternated with short [], and short [] alternated with long []. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 15 of 20 By the time of late Middle English, many words had alternating forms with long and short vowels, but the environmental triggers for the distinction had been lost, e.g. the present and past forms of read.13 Contrastive vowel length thus entered the language, but its use was unstable. Starting in London in the 14th century, the contrast of high vowels // – / / was reinterpreted as a contrast with diphthongs // – / / (later / /).14 This accounts for the shift of the long high vowels to diphthongs. The other long vowels then shifted to fill the gap left by the long high vowels. 5.2. Diensberg Diensberg proposes that the GVS was prompted by the “massive intake of Romance loanwords in Middle English & Early Modern English” (abstract). He cites evidence that alternations in Middle English stressed vowels match alternations in French loanwords. 5.3. Bertacca Bertacca (abstract) refutes Diensberg’s theory, pointing to the loss of inflectional morphology and various other factors as causes for the GVS. 13 Pilch does not say so, but presumably the loss of environmental triggers resulted from the reduction of inflectional complexity described in Section 2. This view is confirmed by Bertacca, who also suggests several other possible triggers for the GVS. 14 Pilch does not address what motivated this reinterpretation, but it could have been dissimilation, changing the long form to make the contrast more noticeable. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 16 of 20 6. Various Ramifications of the Great Vowel Shift 6.1. Effects on Spelling The written form of the London dialect became the standard written form of English between 1450 and 1500. The written language continued to develop in response to certain changes in the spoken language during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (Moore 113). However, the spelling of most English vowels is frozen at a form which precedes the Great Vowel Shift. This explains why English vowel symbols no longer correspond to the sounds they once represented in English and still represent in other modern languages. (Baugh and Cable 239) 6.2. Scottish Dialect All modern dialects of English outside the British Isles derive from the standard London dialect of the seventeenth century. Various local dialects of England, Ireland and Scotland trace their roots to an earlier source. (Moore 113) The land of Scotland was apparently overlooked by the Great Vowel Shift. This explains why modern Scottish English contains such words as [] ‘down’ and [] ‘clean’.15 15 I found no mention of this phenomenon, nor do I have any native Scots available as language helpers. The examples are taken from memory. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 17 of 20 7. Further Research 7.1. Germanic Roots The preponderance of English data used to demonstrate the Great Vowel Shift in the literature have Latin roots. It might be helpful to trace words of Germanic origin to see whether the generalizations hold. If confirmed, this would tend to support the interpretation of the GVS as a phonological phenomenon; otherwise, it would tend to support a morphological theory, where Latinate words underwent a lexical transformation. Various authors mention that Great Vowel Shift in English bears some similarity to shifts in Dutch and other Germanic languages. Johnston (abstract) suggests that these shifts are genetically related, but Awedk and Hamans (abstract) disagree. In any case, this tends to refute the hypothesis that the English GVS was a purely Latinate phenomenon. Comparing the GVS with shifts in other languages might help identify cross-linguistic patterns. 7.2. Scottish The Scottish phenomenon merits more investigation. If the theory is correct that the Scottish dialect(s) of English never underwent the Great Vowel Shift, a close examination might reveal insights into the character of Middle English and the ensuing diachronic change. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 18 of 20 7.3. Alternate Theories Recent journal articles go well beyond the theories discussed in this paper. A full study would need to take into account all of the current theories. 8. Conclusions The loss of the complex Old English inflectional system led to an unstable contrast of vowel length, which in turn led to an upward shift of the long vowels, with the highest vowels becoming strong diphthongs. The simplest interpretation would seem to be that the underlying representations were not changed, but rather new phonological rules were introduced into the language. The phonological derivations must occur at the lexical level to account for various exceptions. Many English spellings reflect the older pronunciations. LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 19 of 20 9. References For several journal articles listed here, only the abstract was available. These are so indicated. Anderson, John M., and Charles Jones. Phonological Structure and the History of English. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1977. Awedyk, Wieslaw and Camiel Hamans. “Vowel Shifts in English and Dutch: Formal or Genetic Relation?” Folia-Linguistica-Historica; 1989, 8, 1-2, 99-114 (abstract only). Baugh, Albert C., and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 3rd ed. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978. Bertacca, Antonio. “The Great Vowel Shift and Anglo-French Loanwords: A Rejoinder to Diensberg 1998.” Folia-Linguistica-Historica; 2000, 21, 1-2, 125-148 (abstract only). Chomsky, Noam, and Morris Halle. The Sound Pattern of English. New York: Harper & Row, 1968. Diensberg, Bernhard. “Linguistic Change in English: The Case of the Great Vowel Shift from the Perspective of Phonological Alternations Due to the Wholesale Borrowing of Anglo-French Loanwords.” Folia-Linguistica-Historica; 1998, 19, 1-2, 103-117 (abstract only). Giancarlo, Matthew. “The Rise and Fall of the Great Vowel Shift? The Changing Ideological Intersections of Philology, Historical Linguistics, and Literary History.” Representations; 2001, 76, fall, 27-60 (abstract only). LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003 Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift Page 20 of 20 Giegerich, Heinz J. English Phonology: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Johnston, Paul A., Jr. “Lass's Law and West Germanic Vowel Shift.” Folia-LinguisticaHistorica; 1989, 10, 1-2, 199-261 (abstract only). Kenstowicz, Michael. Phonology in Generative Grammar. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1994. Lass, Roger. English Phonology and Phonological Theory: Synchronic and Diachronic Studies. Camridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976. Moore, Samuel. Historical Outlines of English Phonology and Morphology. Ann Arbor: George Wahr, 1925. Pilch, Herbert. Manual of English Phonetics. München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1994. Schendl, Herbert and Nikolaus Ritt. “Of Vowel Shifts Great, Small, Long and Short.” Language-Sciences; 2002, 24, 3-4, May-July, 409-421 (abstract only). Smith, Jeremy J. “Dialectal Variation in Middle English and the Actuation of the Great Vowel Shift.” Neuphilologische-Mitteilungen; 1993, 94, 3-4, 259-277 (abstract only). LD 5332 Applied Phonology Ed Kenschaft Spring 2003