National Occupational Standards in Management

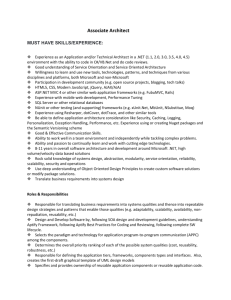

advertisement

Paper prepared for SAM/IFSAM VIIth World Congress: Management in a World of Diversity and Change. 5-7 July, 2004, Göteborg, Sweden. Academic stream: Management education. Leadership Standards: Pros and cons of a competency approach Richard Bolden (contact author) and Jonathan Gosling Centre for Leadership Studies University of Exeter Crossmead Barley Lane Exeter EX4 1TF UK Tel: +44 (0)1392 413018 Fax: +44 (0)1392 434132 Email: Richard.Bolden@exeter.ac.uk Website: www.leadership-studies.com 1 Leadership Standards: Pros and cons of a competency approach Abstract The pros and cons of a competency/standards approach to leadership and management development have been under debate for some time. Whilst many people now question the validity of this approach, organisations in all sectors continue developing their own frameworks and the government encourages and promotes occupational standards. In the current paper, the authors draw upon their experiences of working alongside consultants developing the new National Occupational Standards in Management and Leadership to present some theoretical and practical reflections on this approach. Our experiences have led us to conclude that the development of frameworks and standards can be a valuable way of encouraging individuals and organisations to consider their approach to management and leadership development, but that it is in the application of these standards and frameworks that difficulties can occur. When working with frameworks and standards there is frequently a temptation to apply them deductively to assess, select and measure leaders rather than inductively to describe effective leadership practice and stimulate debate. With an increasing awareness of the emergent and relational nature of leadership it is our opinion that the standards approach should not be used to define a comprehensive set of attributes of effective leaders, but rather to offer a “vocabulary” with which individuals, organisations, consultants and other agents can debate the nature of leadership and the associated values and relationships within their organisations. 2 Introduction The notion of management competence owes much of its origin to the work of McBer consultants for the American Management Association in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The aim of this work was “to explain some of the differences in general qualitative distinctions of performance (e.g. poor versus average versus superior managers) which may occur across specific jobs and organisations as a result of certain competencies which managers share” (Boyatzis, 1982, p9), with a job competency being defined as “an underlying characteristic of a person which results in effective and/or superior performance in a job” (ibid, p21). This concept was widely adopted as a basis for management education and development in the UK following the Review of Vocational Qualifications report in 1986 (De Ville, 1986) and continues to gain dominance. Following the Council for Excellence in Management and Leadership research (CEML, 2002), for example, the government pledged to address the national management and leadership deficit through a range of initiatives to increase demand and improve supply of management and leadership development (DfES, 2002). As these initiatives are rolled-out across the country the emphasis on evidence-based policy, measurable performance outcomes and consistency of approach encourages increased reliance on government-endorsed models, frameworks and standards. Two of the most influential frameworks currently under development in the UK are the Investors in People Leadership and Management Model (IiP, 2003) and the National Occupational Standards (NOS) in Management and Leadership (MSC, 2003). Both of these build upon existing and recognised awards, but where they differ is in the increasing emphasis on “leadership” as well as management. Similar initiatives are underway in other sectors of UK activity, including the National Standards for Headteachers, NHS Leadership Qualities Framework, Defence Leadership Framework, as well as numerous company-specific frameworks. In this paper, the authors will draw on their involvement in the development of the most recent set of NOS in management and leadership to highlight the methodological and theoretical weaknesses of this approach and explore alternative approaches to developing management and leadership capability. National Occupational Standards in Management NOS in Management were first introduced in the UK in 1992. The aim of this initiative was to address the relatively low level of education and training of UK managers in relation to their overseas counterparts by providing a benchmark against which they could evaluate their management behaviour and performance. The standards also fed into the National Vocational Qualifications (NVQ) system to provide a framework for the assessment and award of vocational awards in management [for a more detailed description of the initial development of these standards please see Holmes, 1993]. In 1997 the standards were reviewed and updated by the Management Charter Initiative (MCI) and divided management into seven key roles (manage activities, manage resources, manage people, manage information, manage energy, manage quality, and manage projects) each of which comprised a number of units of competence, with associated performance criteria, knowledge requirements, evidence requirements and examples of evidence (MCI, 1997). The underlying philosophy behind this framework is of the universal nature of management competencies, as revealed by following bold statement from the Management Standards Centre: “The standards were developed with the help of thousands of managers in all types of organisations and represent the acknowledged best practice indicators for management at every level. Whatever the size of your organisation, you will find the standards have been written to meet your management needs.” (MSC website, December 2003). The response to these standards has been mixed, to say the least. Whilst they may have been welcomed by agencies wishing to promote qualifications in management and are being used in some 10% of all UK businesses (Winterton and Winterton, 1997), their effectiveness with regards 3 to improving actual managerial performance is unclear. Winterton and Winterton (1997) conclude from an analysis of 16 case studies that integrating the MCI standards with organisational strategy can enhance the link between management development and business performance through the structure that they provide. Grugulis (1997), however, argues that any benefits of the standards arise solely from their normative function and a desire of managers to legitimise their role. Critics of the standards approach to management attack it on a number of dimensions. Firstly it is criticised for being overly reductionist: “it has been extensively criticised for weaknesses in its ability to represent occupations which are characterised by a high degree of uncertainty, unpredictability and discretion, and its arguable tendency – contrary to the aims of the model on which it is based to atomise work roles rather than represent them holistically” (Lester, 1994, p28). Thus, it is argued that standards tend to fragment the management role into constituent elements rather than representing it as an integrated whole. Whilst this simplification and objectification of management is one of the main attractions of the competency approach, what is represented is far removed from the actual reality of being a manager (Lester, 1994; Grugulis, 1997). Managers operate in uncertain environments, their experience is highly subjective and contextual, and their behaviours result from a complex interaction between internal beliefs, values, knowledge, understanding, skills, and experience and the external world – in this case, the whole is far greater than the sum of its parts. Secondly, standards are criticised for being overly universalistic. As demonstrated by the earlier MSC quote, there is an assumption that the management standards are equally relevant to managers in small and large organisations, senior or junior positions, different industrial sectors, different cultures and facing different challenges and situations. Whilst there may be some evidence to support a set of more generic leadership and management qualities, it would be foolhardy to expect all situations to demand the same type of leadership response. A third criticism is the manner in which standards may reinforce rather than challenge traditional ways of thinking about management (Lester, 1994). Their focus on current “best practice” also means that they may date quickly and, in effect, represent “driving using the rear view mirror” (Cullen, 1992). Thus, standards can hinder rather than encourage a reconsideration of the manner in which management is conceived and applied within organisations, especially with regards to those aspects of the job that are prone to change (e.g. the impact of new technologies and globalisation). A fourth criticism of standards is their emphasis on measurable behaviours and outcomes (Bell et al., 2002) thus it is argued that the very processes of evidence gathering and assessment demanded by the standards approach may actually inhibit organisational learning and development by promoting a focus on observable behaviours and indicators to the exclusion of less overt aspects such as values, beliefs and relationships. A fifth common criticism of the standards approach is its rather limited and mechanistic approach to education: “In a sense the problem at the heart of the standards was that they avowedly offered training rather than education. Whereas training endeavours to impart knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary to perform job-related tasks and to improve job performance in a direct way, education is a process whose prime purposes are to impart knowledge and develop cognitive abilities” (Brundrett, 2000, p. 364). Development of the New NOS in Management and Leadership Despite (or perhaps in response to) these and other criticisms, and following government calls for an inclusion of the “softer” skills of leadership, the Management Standards Centre commissioned a revision of the existing NOS in management in 2003. The new standards are intended to represent a “world class” standard of management and leadership for use both as a benchmark of best practice and as the basis for the NVQ and SVQ (National and Scottish Vocational Qualifications) awards in management. It is also intended that the standards will inform the establishment of the Chartered Manager award from the Chartered Institute of Management. 4 In the first part of 2003 the Management Standards Centre completed an occupational mapping exercise and developed a “functional map” of management and leadership (Figure 1) that provided a framework within which the new management and leadership standards could be situated. [FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE] This map supersedes the previous key role model and divides management and leadership into six key functions: providing direction, facilitating change, achieving results, working with people, using resources, and managing self & personal skills. For each of these elements, the framework defines outcomes, behaviours, knowledge & understanding and skills. To accelerate the process of standards development, the MSC recruited six different sets of consultants to develop standards for each domain of the functional map. Despite our reservations about the approach, we agreed to assist the consultant charged with developing the standards on “Providing direction”, which comprised the elements of “developing a vision for the future”, “gaining commitment and providing leadership” and “providing governance”. Our main contribution was to compile a report summarising significant leadership theory, presenting a range of leadership qualities frameworks used across the public and private sector, and highlighting some alternative approaches to leadership and management development. Following this report, the consultant modified and updated the existing standards. A subsequent phase of research involved discussing these draft standards with a selection of interviewees to gain their reactions. Review of competencies Our review of leadership theory covered the main developments in leadership thinking from the trait approach through the behavioural and contingency schools, situational leadership, transactional and transformational leadership and distributed leadership. In addition, we compiled nine public sector, nine private sector and eight generic leadership and management frameworks currently in use, as well as a selection of leadership development programmes (Bolden et al., 2003). From this review we concluded that a somewhat moderated version of transformational leadership (e.g. Burns, 1978; Bass and Avolio, 1994) tends to be promoted in most frameworks. Whilst many go beyond simple definitions of behaviours, to consider the cognitive, affective and inter-personal qualities of leaders, the role of followers is usually only acknowledged in a rather simplistic, unidirectional manner. Leadership, therefore, is conceived as a set of values, qualities and behaviours exhibited by the leader that encourage the participation, development, and commitment of followers. It is remarkable, however, how few of the frameworks we reviewed (only eight out of 26) referred to the leader’s ability to “listen” and none mentioned the word “follow” (following, followers, etc.). The “leader” (as post holder) is thus promoted as the source of “leadership”. He/she is seen to act as an energiser, catalyst and visionary equipped with a set of abilities (communication, problemsolving, people management, decision making, etc.) that can be applied across a diverse range of situations and contexts. Whilst contingency and situational leadership factors may be considered, they are not generally viewed as barriers to an individuals’ ability to lead under different circumstances (they simply need to apply a different combination of skills). Fewer than half of the frameworks reviewed referred directly to the leaders’ ability to respond and adapt their style to different circumstances. In addition to “soft” skills, the leader is also expected to display excellent information processing, project management, customer service and delivery skills, along with proven business and political acumen. They build partnerships, walk the talk, show incredible drive and enthusiasm, and get things done. Furthermore, the leader demonstrates innovation, creativity and thinks “outside the box”. They are entrepreneurs who identify opportunities - they like to be challenged and they’re prepared to take risks. 5 Of interest, too, is the emphasis on the importance of qualities such as honesty, integrity, empathy, trust and valuing diversity. The leader is expected to show a true concern for people that is drawn from a deep level of self-awareness and personal reflection. This almost evangelistic notion of the leader as a multi-talented individual with diverse skills, personal qualities and a large social conscience, however, posses a number of difficulties. Firstly it represents almost a return to the early “great man” theories of leadership, which venerate the individual to the exclusion of the team and organisation. Secondly when you attempt to combine attributes from across a range of frameworks the result is an unwieldy, almost over-powering list of qualities such as that generated during the CEML research (Perren and Burgoyne, 2001), that identified 83 management and leadership attributes, condensed from a list of over 1000. And thirdly there is little evidence in practice that the “transformational” leader is any more effective with regards to improving organisational performance than his/her alternatives (Gronn, 1995). To a large extent these difficulties are a direct result of the functional analysis methodology central to the standards approach. This method generates a list of competencies from analysis of numerous managers jobs – the result, therefore, is not a list of activities/behaviours demonstrated by any one individual, rather an averaging out across multiple individuals. Imagine if a similar technique was used to determine the characteristics of the “lovable man”: they’d be caring, strong, gentle, attractive, kind, etc. – in effect an unlikely, if not impossible, combination. Whilst personal qualities of the leader are undoubtedly important they are unlikely to be sufficient in themselves for the emergence and exercise of leadership. Furthermore, the manner in which these qualities translate into behaviour and group interaction is likely to be culturally specific and thus depend on a whole host of factors, such as the nature of the leader, followers, task, organisational structure, national and corporate cultures. Review of the draft standards Following our review of leadership theory and competency frameworks we conducted semistructured interviews with eight experienced managers from a range of sectors (including manufacturing, education, finance and defence) and organisation types (public and private sector, large and small, national and multi-national, etc.) and two academic specialists in management learning and development to gain their reactions to the draft standards on “providing direction”. These interviews were supplemented by a number of less formal discussions with other managers, academics and policy makers about the standards approach more generally. Whilst interviewees demonstrated a range of opinions, a number of general reactions to the NOS became evident. On a positive note, the functional map was quite well received (especially by practising managers) as a representation of the management and leadership role. On a less positive note, there was an almost universal resistance to the excessive degree of detail provided within individual units. Whilst it was agreed that this might offer a useful directory or checklist of management activities, it was felt to be unworkable as practical tool. Furthermore, the Providing Direction part of the framework was felt to be too static to represent leadership and management in complex and changing environments and failed to highlight the importance of self-awareness, reflection and shared leadership. There was also a feeling that the standards did not really say anything new about management and leadership and were in no way motivational or inspirational. Only one interviewee showed any real interest in using the standards in their organisation and in this case, specific units would be distributed to selected members of the management team and adapted to the requirements of the organisation rather than used to assess the leadership and management capability of any one individual. With regards to competency frameworks more generally, the very fact that many organisations will go to great effort and expense to develop their own leadership framework is perhaps evidence in itself that there is no “one size fits all” model, even if there does seem to be a fair degree of similarity between them. Perhaps, in this case, it is not so much the framework in itself that is important, but the process by which it is developed. 6 For many of the organisations with which we spoke, the leadership competency framework is an integral element of the leadership development process – whereby it is used to define the content and mechanism of delivery and to help individuals measure and explore their own level of development. It frequently forms the basis of the 360-degree feedback process, by which they can monitor their progress and identify personal learning and development needs, and also underlies assessment and appraisals. A number of organisations expressed the importance of keeping the framework to a manageable number of dimensions (up to seven or eight) so that it remains easier to operationalise. Experience of larger frameworks (such as the previous NOS in management) confirms that longer lists may result in a box-ticking mentality that does little, if anything, to enhance leadership and management capability. Emergent and collective leadership The findings of our review are very similar to those of another recent review of leadership and leadership development literature for the Learning and Skills Research Centre (Rodgers et al., 2003; LSDA, 2003). The authors developed a useful model for the consideration of both leadership and leadership development along two dimensions: individual to collective and prescribed to emergent (see Figure 2). [FIGURE 2 – ABOUT HERE] It is proposed that the vast majority of current leadership initiatives lie within Cell 1 of the grid (prescribed and individual), with most of the remainder in Cell 2 (emergent and individual). Very few initiatives address the right-hand side of the grid and the authors challenge us to consider a more “collective” notion of leadership and leadership development such as that promoted in the distributed leadership literature (e.g. Spillane, 2001). Despite the apparent incompatibility between competency-based approaches and more emergent and collective concepts of leadership and leadership development, however, it is not uncommon to find emergent and collective methodologies being used within programmes closely associated with a competencies/qualities framework. In the NHS, for example, whilst the underlying framework for leadership development is the NHS Leadership Qualities Framework (NHS Leadership Centre, 2002) it is understood that many of these qualities can only be developed through more experiential and reflective learning opportunities such as study tours and exchanges (Blackler and Kennedy, 2003). Similar trends can be observed at the National College for School Leadership, which is increasingly moving from a leadership competencies model (Hay McBer, 1999) towards a more fluid leadership development framework that specifies a strategy for developing school leaders and promoting leadership at all levels (NCSL, 2003). The paradox of leadership and management standards In our research we have encountered a number of paradoxes that encourage a reconsideration of the standards approach to management and leadership development as promoted by the National Occupational Standards. Firstly, the latest set of standards endeavours to present a “world class” benchmark of management and leadership capability whilst also providing the basis for vocational awards in management. These aims are at odds as providing a measurable assessment of actual management performance (e.g. for vocational qualifications in management) is quite different from establishing an aspirational standard of best practice in management and leadership. Secondly, in attempting to describe the management and leadership role in detail, the framework focuses on the role of the individual to the exclusion of the wider organisation. This leads to two problems: an unrealistic expectation of the capabilities of any single individual; and a neglect of many of the more subtle aspects of leadership and management (such as inter-personal relationships, adaptability, the role of followers, and shared leadership) which are perhaps most instrumental to ensuring success. 7 A related paradox, is that in the endeavour to create a truly universal set of management and leadership standards, the NOS provide a set standards that are so generic as to be virtually meaningless in practice. The standards fail to capture the essence of leading and managing in different contexts and offer no guidance about how to adapt your style to the situation (e.g. public versus private sector, large versus small organisations, local versus multinational, etc.). Fourthly, by attempting to introduce the elements of leadership into the new NOS the management standards lose some of their focus. Whilst it is reassuring that the importance of leadership is recognised, leadership is not an occupation in the same way as management. Managers are recruited to specific management roles, with associated responsibilities, and whilst they may be required to exert leadership, the manner in which this is done and the observable outcomes are far harder to define. Fifth, although standards may define the qualities expected from managers and leaders, many of these demand a less prescriptive approach to their development. Qualities such as honesty, integrity and empathy cannot be taught, rather they need to be encouraged to develop through a process of reflection, experience, awareness and belief. Thus, whilst one of the main attractions of the standards approach is to clarify best practice, they provide little guidance as to how to achieve this. Sixth, vocational qualifications are future-orientated, being used as a basis for predicting the future performance of an individual (Holmes, 1993). The assessment of individuals, however, is based on documented “evidence” that has a doubtful relationship with the true nature of managerial work, nor how they will respond within different contexts and/or situations over time. Seventh, the competency and standards approach has at its core a notion of rationality but as Watson points out “because of the ever-present tendency for unintended consequences to occur, [formally rational means] often turn out not to lead to the goals for which they were intended (thus making them materially irrational). In fact, the means may subvert the very ends for which they were designed.” (Watson, 1987, p.49 cited in Grugulis, 1997). We could continue, however, the purpose of this paper is not to dismiss the standards approach out of hand, but to consider alternative ways of addressing the issues for which they were developed. Beyond standards and competencies At the heart of the standards/competencies approach is a desire to be both descriptive and normative - this dual objective is both a key to their popularity and unpopularity. Whilst there can be great practical benefits from describing effective practice, the manner in which this is done in the current NOS in management and leadership is not relevant to most managers lived experience. Likewise the normative function of the management standards qualifications in terms of specifying the behaviours and characteristics required of managers, whilst useful in theory fails to be very effective in practice. So how could these objectives be better served? Benchmarking best practice in management and leadership In attempting to present a comprehensive and universal picture of management and leadership qualities, the NOS provide a framework that bears little relation to what any actual manager does. A more appropriate approach might be to present real-life case studies of management and leadership in different contexts and situations that can be read as and when appropriate. The fact that every organisation and situation is unique, however, will mean that case study material will only go part way to revealing how leadership and management should look within a given context. A more comprehensive checklist of management and leadership behaviours, skills, outcomes, etc. (such as given in the NOS) could used in conjunction with case studies to offer a vocabulary with which to discuss management and leadership more widely and to develop a profile tailored to the organisation. Such an approach could help facilitate organisations looking to develop their own leadership and management frameworks, by encouraging them to consider and debate the meaning of leadership and management within their context. The identification of what is required (or desired) of leaders and the manner in which this integrates with other activities (such as the definition of corporate 8 values) is an important voyage of discovery for the organisation and one for which it is vital that key players take ownership. To achieve this takes time, reflection and discussion - simply printing off or copying a pre-defined set of standards wouldn’t achieve the same results. Assessing and developing management and leadership capability If the NOS in management and leadership don’t reflect what leaders and managers actually do, nor are they based on empirical evidence indicating a direct link between management and leadership competencies and improved performance, then they are unlikely to be effective at assessing management and leadership capability. Rather than considering the behaviours that leaders and managers should exhibit, maybe it would be better to consider what abilities they will require in order to deal effectively with future challenges. A recent approach to management education proposed by Gosling and Mintzberg (2003) moves the focus of executive education from a functional model (such as used traditionally in MBAs) to a cognitive model. In this approach, it is argued that what the effective manager needs to master is a series of “mindsets” rather than a pre-defined list of skills and behaviours (see Figure 3). [FIGURE 3 ABOUT HERE] The attractions of such an approach over standards and competencies include that: they treat the manager holistically, they are adaptable to different contexts and situations, and they inform development. Furthermore, the model in its simplicity is far easier to apply in practice, being motivational rather than prescriptive. Conclusions It has been argued that whilst the NOS in management and leadership have been developed to address very practical concerns (providing a benchmark of best practice and a framework for assessment and development) they are too conceptually and methodologically flawed to be of much practical benefit on their own. Dismissing the standards approach out of hand, however, is unconstructive as it does not help practitioners deal with the problems for which they were developed. In this paper we have argued for a more inductive application of the standards, as a means for opening a dialogue about management and leadership within organisations and providing examples of effective practice, rather than prescribing (deductively) what an effective manager should do. Perhaps their association with a best practice database would help improve their relevance and applicability to different sectors and settings and help bring them to life for practicing managers. Standards and competencies should thus aim be more inclusive. They should be tailored and modified for specific organisations and their staff; should be more accessible (and condensed); and should aim to be inspirational rather than descriptive. The focus on individual behaviours should be extended to permit a broader appreciation of the cognitive, affective and relational aspects of leadership and management and particularly the role of shared and distributed leadership within organisations. Furthermore, extensive research is required to ensure that the competencies and behaviours being promoted are directly and causally related to effective leadership in all its facets. References Bass, B.M. & Avolio, B.J. (1994) Improving Organizational Effectiveness Through Transformational Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Bell, E., Taylor, S. and Thorpe, R. (2002) “A Step in the Right Direction? Investors in People and the Learning Organization”. British Journal of Management, Vol 13, 161-171. Blackler, F. and Kennedy, A. (2003) The Design of a Development Programme for Experienced Top Managers from the Public Sector. Working Paper, Lancaster University. Boyatzis, R.E. (1982) The Competent Manager: a model for effective performance. New York, Wiley. 9 Brundrett, M. (2000) “The Question of Competence; the origins, strengths and inadequacies of a leadership training paradigm”. School Leadership and Management, 20(3), pp. 353-369. Burns, J. M. (1978) Leadership. New York: Harper & Row. CEML (2002) Managers and Leaders: Raising Our Game. London, Council for Excellence in Management and Leadership. Cullen, E. (1992) A vital way to manage change. Education, November 13, pp.3-17. De Ville, O. (1986), The Review of Vocational Qualifications in England and Wales. MSC/DES, London, HMSO. DfES (2002) Government Response to the Report of the Council for Excellence in Management and Leadership. Nottingham, DfES Publications. Gosling, J. and Mintzberg, H. (2003) “The Five Minds of a Manager”. Harvard Business Review, November 2003. Gronn, P. (1995) Greatness Re-visited: The current obsession with transformational leadership. Leading and Managing 1(1), 14-27. Grugulis, I. (1997) “The Consequences of Competence: a critical assessment of the Management NVQ”. Personnel Review 26(6), pp. 428-444. Hay McBer (1999) School Leadership Model. National College for School Leadership. Holmes, L. (1993) The Domestication of Management Knowledge? Recent UK State Intervention in Management Education. Prepared for EGOS Colloquium, "The Production and Diffusion of Managerial and Organizational Knowledge", July 1993. IiP (2003) Leadership and Management Model. London: Investors in People UK. Lester, S. (1994) “Management standards: a critical approach”. Competency 2 (1) pp 28-31, October 1994. LSDA (2003) Leading Learning Project Work Package 1: International Comparator Contexts. Learning and Skills Development Agency Research Findings Report, July 2003. MCI (1997) National Occupational Standards in Management. London: Management Charter Initiative. Available online at: www.management-standards.org.uk. MSC (2003) Draft National Occupational Standards in Management and Leadership. Management Standards Centre working document. NCSL (2003) Leadership Development Framework. National College for School Leadership, source: http://www.ncsl.org.uk/index.cfm?pageid=ldf NHS Leadership Centre (2002) NHS Leadership Qualities Framework. Source: http://www.NHSLeadershipQualities.nhs.uk Perren, L. and Burgoyne, J. (2001) Management and Leadership Abilities: An analysis of texts, testimony and practice. London: Council for Excellence in Management and Leadership. Rodgers, H., Frearson, M., Holden, R. and Gold, J. (2003) The Rush to Leadership. Presented at Management Theory at Work conference, Lancaster University, April 2003. Spillane JP, Halverson R, Diamond JB (2001). Towards a theory of leadership practice: a distributed perspective. Institute for Policy Research Working Paper, Northwestern University. Watson, T.J. (1987) Sociology, Work and Industry. London, Routledge and Kegan Paul. Winterton, J. and Winterton, R. (1997) “Does Management Development Add Value?” British Journal of Management, Vol.8 Special Issue, S65-S76, June 1997. 10 Figures Figure 1 - Draft Functional Map of Management and Leadership (Management Standards Centre, 2003) http://www.managers.org.uk/msu2001/functionalmap.htm Figure 2 – LSRC Leadership Framework (Source: LSDA, 2003) http://www.lsda.org.uk/files/PDF/LSRC533RF1.pdf 1 – Managing self: the reflective mind-set 2 – Managing organisations: the analytic mind-set 3 – Managing contexts: the worldly mind-set 4 – Managing relationships: the collaborative mind-set 5 – Managing change: the action mind-set Figure 3 – Mindsets for Managers (Gosling and Mintzberg, 2003) 11