USN LT Christian`s Little Blue Book

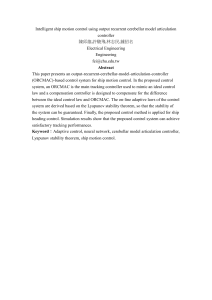

advertisement