KEEP BREATHING - Malcolm Hart, Ph.D.

advertisement

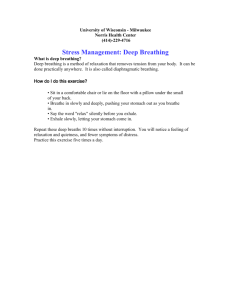

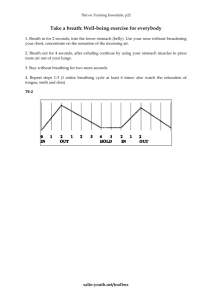

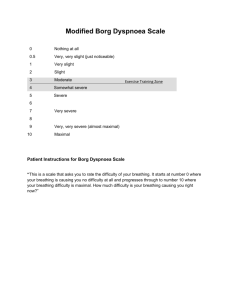

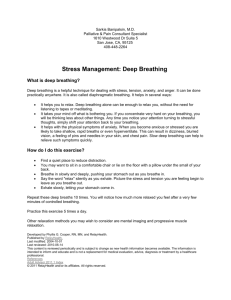

KNOW YOUR STRESS STYLE. AND, KEEP BREATHING! Mac Hart, Ph.D. In the past 24 years, I have evaluated well over 4,000 police and deputy sheriff applicants at the oral board interview. In nearly every one of those board interviews, I asked the law enforcement applicant some version of the following question: “How do you know when you are stressed? What personal cues alert you to the fact that your tension is increasing or that your stress level is climbing?” I am alarmed when police applicants gaze back at me with blank looks on their faces, with seemingly no idea what I am talking about, and/or who calmly insist - “I don’t ever get stressed.” To function well as a human being and to respond adaptively to stressful life events, it is imperative that each of us learns to identify (1) the types of things, events, people that cause us stress and (2) the kinds of actions, choices, and adjustments that we can employ to help to alleviate that stress. Such awareness is essential for good physical health, emotional health, and successful job performance. The stakes are even higher in law enforcement work where officers are called upon to make split-second decisions in high-risk situations. Can you imagine the dangers on a police officer on patrol, unaware of his elevated stress level – primed to shut down or over-react with fear or anger when the unexpected occurs? “Stress Style Test: Body, Mind, Mixed?” (Daniel Goleman, Ph.D.) In American Health (August 1987), Dr. Daniel Goleman published the following brief screening test to help people identify their characteristic style of reacting to stress. The bold-text material that follows is quoted directly from Dr. Goleman’s article: the directions, the checklist of symptoms, and the procedure for scoring your personal responses. Imagine yourself in a stressful situation. When you’re feeling anxious, what do you typically experience? Check all that apply: 1. My heart beats faster. 2. I find it difficult to concentrate, because of distracting thoughts. 3. I worry too much about things that don’t really matter. 4. I feel jittery. 5. I get diarrhea. 6. I imagine terrifying scenes. 7. I can’t keep anxiety-provoking pictures and images out of my mind. 8. My stomach gets tense. 9. I pace up and down nervously. 10. I’m bothered by unimportant thoughts running through my mind. 11. I become immobilized. 1 12. I feel I’m losing out on things because I can’t make decisions fast enough. 13. I perspire. 14. I can’t stop thinking worrisome thoughts. “There are three basic ways of reacting to stress – primarily physical, mainly mental or mixed. Physical stress types feel tension in the body--- jitters, butterflies, and the sweats. Mental types experience stress mainly in the mind---worries and preoccupying thoughts. Mixed types react with both responses in about equal measure.” “Give yourself a Mind point if you answered ‘yes’ to each of the following questions: 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 12, 14.” “Give yourself a Body point for a ‘yes’ response to each of these: 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 13.” “If you have more Mind than Body points, consider yourself a mental stress type. If you have more Body than Mind points, your stress style is physical. About the same number of each? You’re a mixed reactor” (p.63). In his article, Daniel Goleman then proceeds to suggest relaxing activities for persons with each type of stress style. For physical stress types, he recommends activities such as: aerobics, yoga, massage, hot tubs or hot baths, walking, swimming, or progressive muscle relaxation. For mental stress types, Goleman suggests the following practices: meditation, reading, crossword puzzles, TV/movies, board games, arts and crafts, or any absorbing hobby. Mixed stress types may want to experiment with a combination of activities from the Mind and Body lists. By all means, learn to manage your personal stress more effectively by selecting some of these kinds of activities to include – on regular basis – in your weekly schedule. These are basically lifestyle changes that can help address accumulated daily stress. But, what can any person do in that very moment when an unexpected stressor occurs? Corrective Breathing – Get The Immediate Benefits Slow, nasal diaphragmatic breathing can be tremendously helpful virtually anytime that a stressful physical or emotional threatens to unbalance us. By altering your breathing pattern in the midst of an anxiety-provoking situation, you can actually slow down, and even reverse, your body’s “panic-provoking symptoms.” Reid Wilson, Ph.D. in his ground-breaking book, Don’t Panic-Taking Control of Panic Attacks, teaches us that in response to any threatening situation (real or perceived), most people (1) increase their respiration rates, (2) shift to an upper chest (thoracic) breathing pattern, (3) and engage in a high degree of mouth breathing – that often takes the form of audible sighing and over-breathing. This over-breathing, or hyperventilating (sub-clinically), results in the body taking in too much oxygen and blowing off too much carbon dioxide. This change in the normal balance of blood gases raises the pH 2 level in the body’s nerve cells – making them more excitable. When this occurs, Dr. Wilson tells us that the body’s “Calming Response” is suppressed and all kinds of uncomfortable physical symptoms begin to occur in conjunction with a panic response. Wilson observes, “Most people who hyperventilate never realize they are doing so. They don’t report that they are having a problem with their breathing” (p.148). So, scratch that image of someone overtly gasping for air, or trying to catch his breath by breathing into a paper bag, when he is hyperventilating. This is how it is generally depicted on the movies or TV, however, it is generally much more subtle than that. “Physical and Psychological Complaints Caused by Hyperventilation” (Reid Wilson, p.148-149) Which of these have you experienced in the throes of a highly stressful situation? Heart palpitations Heartburn Poor concentration Tingling of mouth, hands, feet Chest pain Lump in the throat Stomach pain Muscle pain Muscle spasms Sweating Racing heart Dizziness or lightheadedness Blurred vision Shortness of breath Choking sensation Difficulty swallowing Nausea Shaking Tension, anxiety Fatigue, weakness In effect poor breathing by itself, in response to an anxiety-provoking situation, can throw the body and mind into a panic-like state that greatly reduces an individual’s ability to respond to the stressful event in an adaptive, balanced, and intelligent manner. There is good news. It is fairly easy to learn to monitor your personal stress level and to start using slow, nasal diaphragmatic breathing to help activate the calming response, when something stressful occurs. How To Use Slow Nasal Breathing To Decrease Your Stress Response Please follow these simple steps: 1. Start monitoring your stress level (0-10 scale) throughout the day. Let’s define a “0 to 1” level of stress that extremely relaxed and carefree state of mind/body, such as you might experience in your favorite stress-free place, e.g. lying on a hammock in your back yard. Level “9 or 10”, then, will represent a highly anxious, near panic state of mind and body, 3 where it becomes difficult to think clearly and lots of physical signs of stress are present. Most people report an average stress level of between “2” and “5” when they’re involved in their daily routines, and nothing particularly stressful is occurring. It’s very helpful to know, hour-by-hour, what level of “stress” or “relaxation” you may be experiencing. 2. At the first sign of an “elevated” stress response, begin to employ a slow, nasal breathing (described in step 3 below) pattern. “Elevated” stress is a relative term, so each individual must decide what kind of increase in stress starts to become disruptive or problematic. Generally speaking, people tend to identify stress scores in the “5” to “7” range as elevated. This will vary widely, however, depending upon your level of average stress during the course of the day. Successful intervention requires that you decide what stress level you are defining as “elevated”, then commit to employing this nasal breathing strategy whenever that unacceptable stress level occurs. This will promote the bodymind’s relaxation response. 3. Use the slow nasal, diaphragmatic breathing pattern in a deliberate way until you notice a significant decrease in your stress level. First – make sure that you have stopped any mouth breathing or sighing breaths. As we noted above, that simply makes things worse. Next – simply begin to breathe, a normal amount of air, gently and slowly through your nose, while focusing on filling only the lower part of your lungs (diaphragm or belly area). Then exhale easily through your nose. Repeat this process for a few minutes with a positive and expectant attitude until you begin to experience a calm, warm, and relaxed feeling in your chest, throat, and stomach areas. Reid Wilson, Ph.D. refers to this type of breathing as “natural breathing” (p.150). He suggests that we need to learn to breath from the diaphragm and to make that breathing pattern a regular part of our daily lives. He observes that over time we can learn this new habit of breathing from the belly, which helps us to become more resilient to the brief respiratory elevations associated with events that trigger our stress. In his book, Don’t Panic – Taking Control of Anxiety Attacks, Dr. Wilson offers the following exercise to help us learn this skill of natural breathing: 1. “Lie down on a rug or on your bed, with your legs relaxed and straight and your hands by your side.” 2. “Let yourself breathe normal, easy breaths. Notice what part of your upper body rises and falls with each breath. Rest a hand on that spot. If that part is your chest, you are not taking full advantage of your lungs. If your stomach region (abdomen) is moving instead, you are doing fine.” 4 3. “If your hand is on your chest, place your other hand on your stomach region. Practice breathing into that area, without producing a rise in the chest. If you need help in accomplishing this, consciously protrude your stomach region each time you inhale.” “By breathing into your lower lungs, you are using your respiratory system to its full potential. This is what I mean when I use the term natural breathing: gentle, slow, easy breathing into your lower lungs and not your upper chest. It is the method you should use throughout your normal daily activities” (p.150-151). 4. Strive to make this slow nasal diaphragmatic (“natural”) breathing pattern a regular and normal part of your daily life. Good “natural breathing” alone can do much to maintain the body’s calming response as well as to fend off or slow down the body’s emergency response when stressful events occur. So, practice it continually throughout the day – anytime that you are not exercising, or exerting yourself physically. You can maintain a sense of balance and emotional well being by practicing slow nasal breathing in your car, while interacting with others, or even while managing the various tasks and duties of your work day.. 5