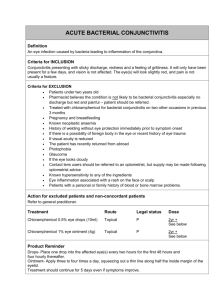

ACUTE BACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

advertisement

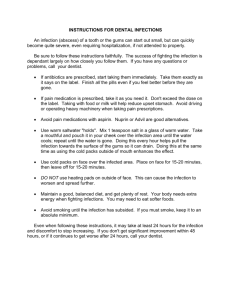

ACUTE BACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS Introduction Acute conjunctivitis can be: ● Bacterial ● Viral ● Allergic ● Irritative/ chemical Whilst acute bacterial conjunctivitis is usually easily diagnosed on clinical grounds, milder cases can be difficult to distinguish from viral or allergic causes. In most cases empiric treatment for bacterial infection is undertaken. Caution should be taken when assessing at risk groups for serious causes, such as gonococcus or trachoma. The important differentials of herpes infection or hypopyon must also be kept in mind. Epidemiology ● Acute bacterial conjunctivitis is widespread throughout the world. ● Outbreaks of gonococcal conjunctivitis have occurred in northern and central Australia. ● Infection due to Chlamydia trachomatis (trachoma) continues to be a significant public health concern in Aboriginal communities It is a major cause of preventable blindness worldwide. ● The epidemiology of acute bacterial conjunctivitis in Australia due to causes other than trachoma and gonococcal infection is not well documented. ● Infections are most common in children under five years of age and incidence decreases with age. Pathology Organisms The most common bacterial pathogens include: ● Haemophilus influenzae ● Streptococcus pneumoniae Less commonly: ● Staphylococcus aureus ● Pseudomonas aeruginosa ● Neisseria gonorrhoeae ● Neisseria meningitidis ● Chlamydia trachomatis Adenovirus is the commonest cause of viral conjunctivitis Incubation period ● The incubation period for bacterial infection is usually 24–72 hours. ● In the case of trachoma incubation is 5–12 days. Reservoir ● Humans. Mode of transmission ● Infection is transmitted via contact with the discharge from the conjunctivae or upper respiratory tract of infected persons. ● Neonates may acquire infection during vaginal delivery. ● In some areas flies have been suggested as possible vectors. Period of communicability ● It is infectious while there is discharge. Susceptibility & resistance ● Everyone is susceptible to infection and repeated attacks due to the same or different bacteria are possible. ● Maternal infection does not confer immunity to the child. Clinical assessment Left: Bacterial conjunctivitis. Right: Viral conjunctivitis. Left: Allergic conjunctivitis. Middle: Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus with nasociliary nerve involvement. Right: Flourescein stained cornea demonstrating a dendritic ulcer. Whilst acute bacterial conjunctivitis is usually easily diagnosed on clinical grounds, milder cases can be difficult to distinguish from viral or allergic causes. Before a diagnosis of “simple” bacterial conjunctivitis is assumed, important serious causes, as well as important differentials should always be considered. 1. High risk groups: Important serious causes should be considered in high risk groups which include Aboriginal populations and neonates. Trachoma: ● Important epidemiological considerations may alert the clinician to the possibility to Chlamydia infection. In Australia this will include Aboriginal populations in particular. ● Trachoma should be suspected in the presence of lymphoid follicles and diffuse conjunctival inflammation or trichiasis (inturned eyelashes). Neonates: 2. ● Neonates are at higher risk for serious bacterial infection, such as staphylococcus, gonococcus and meningococcus. ● (See also RCH guidelines) Hypopyon: ● 3. Predisposing foreign body: ● 4. Look for and rule out this serious condition, (see separate guidelines) Ensure that the eye has no predisposing foreign bodies. Slit lamp examination ● Slit lamp examination should be undertaken if herpetic infection or foreign body is suspected. ● Nasociliary involvement in patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus will make ocular involvement likely. “Typical” bacterial infection results in: ● Ocular pain, or “grittiness”. ● Photophobia ● Ocular inflammation ● Purulent discharge, (as opposed to the clear discharge of viral infection in most cases). ● Initial unilateral infection rapidly becomes bilateral due to cross contamination (via fingers). Sixty-four per cent of cases of acute bacterial conjunctivitis spontaneously remit within 5 days. Symptoms may however last up to 14 days if untreated. Investigations Mild conjunctivitis is rarely investigated and is usually treated empirically. Microscopic examination of a stained smear or culture of the discharge is required to differentiate bacterial from viral or allergic conjunctivitis. Swabs should be taken for culture and PCR testing when serious bacterial infection, (Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Neisseria meningitidis), or trachoma is suspected. They should also be taken in cases of neonatal infection. Herpes infection can de diagnosed clinically via slit lamp examination. Management Whilst acute bacterial conjunctivitis is usually easily diagnosed on clinical grounds, milder cases can be difficult to distinguish from viral or allergic causes. In most cases empiric treatment for bacterial infection is undertaken. 1. Irrigation: ● Sterile saline irrigation, to clear purulent discharge 2. Discharging eyes should never be padded. 3. Analgesics: ● 4. Anti-irritant drops: ● 5. Simple oral analgesics may give some relief from pain. Topical vasoconstrictors such as phenylephrine 0.12% may provide some symptom relief Antibiotic drops: 2 Chloramphenicol: ● Chloramphenicol 0.5% eye drops, 1 to 2 drops every 2 hours initially, decreasing to 6-hourly as the infection improves. ● Chloramphenicol 1% eye ointment may be used at bedtime Alternatively: Framycetin: ● Framycetin 0.5% eye drops, 1 to 2 drops every 1 to 2 hours initially, decreasing to 8-hourly as the infection improves. Gentamicin, tobramycin and quinolone eye drops are also available however are substantially more expensive than the recommended drugs and are generally unnecessary for uncomplicated empirical treatment. Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Neisseria meningitidis require treatment with systemic antibiotics. Specialist advice must be obtained for these ocular infections. Trachoma also requires systemic antibiotics, erythromycin or Azithromycin, (see Therapeutic Antibiotic Guidelines for full prescribing details). 6. Do not use, ● Topical steroids ● Topical local anaesthetics in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. 7. Referral: Referral to an Ophthalmologist should occur in the following circumstances: ● Failure of resolution with adequate treatment. ● Impairment of vision. ● Herpetic infection ● Suspected or proven Gonococcal or Neisseria infection ● Suspected or proven Chlamydia infection Neonatal conjunctivitis should be referred to a pediatrician. References 1. The Blue Book Website. 2. Therapeutic Antibiotic Guidelines, 13th ed 2006 Dr J. Hayes 8 October 2009