Washington Territory: the Political and Demographic Context

advertisement

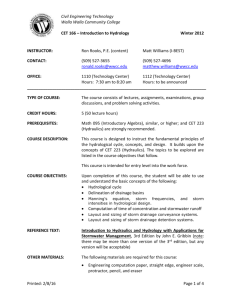

The Battle of Frenchtown (1855), Washington Territory: the Political and Demographic Context rev 9/4/11 Washington State’s newest historic site, Frenchtown, was opened on December 11, 2010. This date commemorated an event which had taken place 155 years earlier, one in which over 1,000 men found themselves engaged in a four-day battle in the Walla Walla Valley. Estimates of the number of men that died in the fighting there total around eighty souls. This paper will focus on four sub-themes: (1) The actual four-day battle between the militia and the warriors of Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Palouse tribes who were defending their area villages; (2) The difficulties faced by the U.S. Army, in the person of the Pacific Division’s Commanding Officer, General John Wool, in establishing its authority and checking the rogue elements within the territorial militia of Oregon and Washington, along with the ambitions of West Point graduate Isaac Stevens, who was now wearing the hat of Washington’s Territorial Governor; (3) The more obscure yet fundamental matter of the actual regional demographics of the Pacific Northwest (PNW) frontier in the 1850s, and why there happened to be a ‘Frenchtown’ located at the site of this battle; and finally, (4) An outline of the migration of these obscure people into the backcountry of the PNW over the second half of the 19 th century. In addition to a point on the map, there was the point in time, all part of a larger process. All across the northern borderlands of the U.S., every time a treaty had been signed from 1763 through 1846, most of the older communities of French-speaking Canadiens located deep in the interior found themselves south of the new line. With them were their Indian wives and families of mixed-blood offspring - then called half-breeds, now generally the term metis is used, for those ‘French-breeds’ among them. Hence, the French-Canadian West found itself in territory that sequentially ended up in the U. S., not in modern Canada. As such, their part of the story has fallen out of Canadian history, and has yet to be written back into America’s national history. Not represented at the negotiations, much like their Indian relations, the treaties ignored the interests and natural allegiances of les Canadiens. . Furthermore, one might remember that during much of the 19th century the ancestors of the modern Anglo-Canadians still referred to themselves as English, Scottish, or Irish subjects of the Crown, rarely as Canadians. At mid-century, in the Pacific Northwest, les Canadiens composed the large majority of the older settler group. And these were a river people. They had their own names for many of the tributaries and lakes of the Columbia-Snake River system. If the modern reader takes a closer look at the map, he will see that many of these names are still there. This applies to major milestones along the river system, also. The principal portage points going up-river through the Columbia River Gorge, were called les Cascades and les Dalles. By 1825 the first of these had been expanded to the entire mountain range penetrated by the gorge. Roughly half-way up, the Columbia River ran parallel to a natural phenomenon they called La Grande Coulee. A century later, a site along the Columbia at the north end of this massive dry canyon was picked for building the highest dam in North America. And so on, with numerous other residual names and topographical terms provided by les Canadiens that are still on our maps. The Battle In an area rich with historic tragedy, the battle occurred two miles west of the ruins of the Whitman Mission in one of the territory’s largest inland settlements east of the Columbia River Gorge. Six months earlier the Walla Walla Treaty had been signed about ten miles further up stream. Located deep in Indian Country, this community stretched along the Walla Walla River for several miles between the modern day city of Walla Walla and the town of Lowden. More precisely, the settlement lay between the confluence of two tributaries of the Walla Walla, Dry Creek and Mill Creek. The community was known to the Americans as ‘Frenchtown,’ and to the locals as le Village des Canadiens. It was situated immediately down stream from the principal village of the Cayuse. 2 The Yakima War started in October of 1855, following a series of murders of whites in the Yakama Country and Puget Sound. Resentment by the Indians to the terms unilaterally imposed in a series of recent treaties is generally considered the principal cause of the series of incidents that led to war. The treaties were imposed between Christmas Day of 1854 and June of 1855 by Isaac Stevens. Stevens was a man wearing two hats, serving as both Washington Territory’s first Governor, as well as its Superintendent of Indian Affairs. When Governor Stevens arrived in the new territory in the fall of 1853, Indians still outnumbered whites by roughly a four to one ratio. Stevens was in a hurry, however. American settlers continued to trickle in looking for free land, and there was no time to waste. With the successful conclusion of the Yakima River campaign in November under Major Rains of the U.S. Army, it appeared that further operations were to be called off until spring. Major Rains had cleared the Valley, working in tandem with the Oregon volunteers under an independent command, but this had amounted to little more than minor skirmishing and looting of Indian food caches and a French Catholic Mission on the Ahtanum River. While the smaller Washington force of volunteer militia were fully occupied in the Puget Sound areas, the more numerous Oregon volunteer units were not to be denied. There had been reports of looting in the Walla Walla Valley by bands of Indians. Rumors passed on by friendly Indians indicated that a number of Walla Walla Indians were planning to attack Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens and a small accompanying force of volunteers, returning with him from the Spokane country. Therefore, Oregon’s Territorial Governor, George Curry, ordered the volunteer units that had missed out on the Yakima Campaign to deploy to the Walla Walla Valley to counter the potential threat to Stevens and his party. The Oregon Mounted Volunteers (O.M.V.) headed out, and up the south bank of the Columbia from the fort at les Dalles, establishing a base near the confluence of the Umatilla River. Then on December 2, after an all night march across difficult terrain from near the mouth of the Umatilla River to that of the Walla Walla River, the O.M.V. reached the abandoned Hudson Bay’s Company (HBC) trading post at the mouth of the Walla Walla River. The post had been 3 pillaged of its blankets and other trading goods, but to the O.M.V.’s disappointment, there were few Indians in site. Hopes of pulling off a surprise attack were frustrated. However, the eager Oregon Mounted Volunteers under the command of the recently elected frontier lawyer named James Kelly, would soon have more opportunities to precipitate a battle. They drove up the valley toward the Walla Walla and Cayuse villages. Kelly, suddenly a militia Lt. Colonel, had displayed sufficient bravado during his campaign speech to get elected to the rank. Now an opportunity to act had presented itself. At his side rode one of the subagents of the Oregon’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Nathan Olney. The Superintendent, Joel Palmer, having learned of the man’s unreliable character through painful experience, had been trying to keep Olney on a short leash, but he had broken loose, again. Concerned for their families along with their recently gathered stores of food for making it through the winter, Walla Walla Chief Peopeo Moxmox, rode out with forty men to ascertain the intentions of this armed suyapo force. (Suyapo was a Columbia basin Indian term for Americans, apparently derived from the French word for the peculiar ornament they always seemed to wear on their heads – le chapeau.) Chief Peopeo Moxmox had long been a friend of the whites. Many of the tribe’s young women had married Canadiens, who had once worked at the nearby trading post or its ranching operation further up stream. Known as a man of moderation, the chief had signed the recent treaty, and all this in spite of his son having been murdered by an American - a crime that had been allowed to go unpunished. The chief first met with a force of a 1/2 dozen metis scouts under Narcisse Cornoyer and Antoine Rivet. Antoine’s father, Francois had accompanied Lewis and Clark in 1804 up the Missouri as far as the Mandan villages of North Dakota. Francois Rivet returned downstream in the spring of 4 1805 with another dozen or so boatmen of Canadien origins, while Lewis and Clark headed for the Pacific with a more Americanized crew. Then Francois was heading back up river in 1806 with Captain McClallen when they shared an encampment with Lewis and Clark returning from the Pacific. Rivet continued up river with McClallen where they reached the headwaters of the Columbia in 1807 by following a returning Flathead band of buffalo hunters via a much more practical crossing of the Continental Divide than that of the Shoshone. Francois stayed on and married a young widow of the continuous warfare with the Blackfeet. His wife was of Flathead and Pend Oreille origins. She later received the baptismal name of Therese, when they retired downstream with their large family to a farm in the Willamette Valley. As for Narcisse Cornoyer, he was a literate and more recent addition to the community of les Canadiens in the Willamette Valley, where he married a metis of Canadien and Chinook Indian origins, Sophie Beleque. Peopeo Moxmox approached under a white flag of truce. A brief discussion in the regional pidgin known as the Chinook Jargon followed, one in which the chief expressed his desire to parley. Once Kelly was alerted that contact had been made, and had caught up with the metis scouts, the chief queried Kelly as to why the soldiers had entered Walla Walla Country. Kelly and Olney were immediately suspicious of the old chief’s willingness to discuss matters. Negotiation meant delay. They suspected treachery. In response to the chief’s willingness to pursue restitution for the looted blankets and livestock from the HBC trading post or local ranchers, Kelly responded with specific demands which amounted to confiscation of all rifles, ammunition, and the Walla Walla tribe’s considerable livestock – both horses and cattle. As for the chief’s conciliatory posture, in his report afterward, Lt. Col. Kelly recalled, “we concluded that this was only a ruse for gaining time to remove his village and preparing for battle. I stated to him that we had come to chastise him for the wrongs he had done our people, and that we would not defer making an attack on his people unless he and his five followers would consent to accompany and remain with us until all difficulties were settled.” [extract from John C. Jackson’s “A Little War of Destiny,” p.120] 5 Chief Peopeo Moxmox and his men were consequently taken hostage. This naturally outraged the balance of the Indian force of several dozen Indians, observing from a nearby hill. Word immediately spread among the tribes of this latest breach of trust by the suyapo. The next morning, December 6, the Oregon Mounted Volunteers (O.M.V.) entered a nearby Walla Walla village that had been deserted. They proceeded to pillage the remaining food supplies. Returning to the O.M.V. baggage camp on the Walla Walla, the next day Kelly’s force continued to advance up the river, while sniping began from Indians on ridge tops. The battle started on the morning of December 7, as a mobile action with small groups of riders circling and skirmishing up, over, and around the hill country extending north of the river valley. Dismounting under the increasingly heavy fire from the defending Indians, battle lines soon stabilized between the cabins of Joseph Laroque and Louis Tellier in le village des Canadiens. But this was not before the O.M.V. had made two charges against the Indians holed up on the Tellier farm. These two charges at the beginning of the battle would account for all eight of the O.M.V.’s fatalities over the entire four-day period. The Laroque and Tellier families along with those of the other Canadiens had withdrawn to one of two locations over the prior weeks as the chaos worsened. One group had headed down river toward les Dalles after the looting by a number of the younger Indians had begun, while the other group of several dozen individuals stayed in the area moving up the Touchet about twenty miles to the northeast. The following March, this latter group was also forced to move down river to les Dalles when the Army decided to start enforcing its earlier ban on settlement east of les Cascades, at least until things settled down. It was outside the Laroque cabin that Volunteers gunned down Chief Peopeo Moxmox and several of his men on December 7. Once it was apparent that a serious battle was underway, Lt. Col. Kelly decided that the prisoners needed to be tied-up to free up their guards. The chief 6 and his men resisted, and were killed for it. The chief’s body was then mutilated with ears and other parts cut off for trophies to be displayed once back in the Willamette Valley. source: John C. Jackson 1 7 Assaults, skirmishing and flanking operations continued over the next four days, shifting back and forth as the lines extended up from the brush along the river up over the ridge located to the north, where the cemetery of the St. Rose Catholic Church would soon lie. Both sides dug numerous rifles pits (fox holes) all along the fluid battle line. Small units of each party would move forward, but be forced back due to exposure to cross fire on their flanks. As in many battles, the timely arrival of reinforcements and supplies proved critical. First the Indians gained a momentary advantage with the arrival of around 100 Palouse warriors. Ammunition was beginning to run low on both sides, however. When two companies of reinforcements showed up to bolster the O.M.V. positions on December 10, the Indian warriors decided to withdraw from the battlefield. This too was accomplished in an orderly manner. Unfortunately, several days later, the villagers panicked while crossing the Snake about 50 miles to the northeast. Several dozen Indians drowned and hundreds of horses were lost. Estimates of fatalities at the battle site of Frenchtown included the original eight O.M.V. soldiers, and roughly 70 odd Indian warriors. The O.M.V. force also suffered 17 wounded. Quoting from John C. Jackson’s “A Little War of Destiny,” Next morning the Indians had evaporated. The arrival of the relief column had convinced them to give up the fight and evacuate the tribe and as much property as they could salvage. As the fleeing warriors whipped along the Nez Perce Trail, they passed the Metis camp on the Touchet River and pulled up for a moment to tell the half-breeds that they would have beaten the whites if the reinforcement hadn’t arrived…. As they [an OMV detachment of 60 volunteers] continued, the pursuers met a Nez Perce Indian bringing a message from Narcisse Raymond, who was with the Metis assembled in a group camp on the Henry Chase claim on the upper Touchet. It was suspicious that they had remained safe while the fight was going on. When the Metis asked for protection, they were put under the care of Company K [the Willamette Valley Metis unit]. Although proximity to the army was not in their best interests, the Metis were ordered to move nearer the volunteer camp so they could be properly supervised. [ JCJ pp.139-40] As elsewhere in the West many local Indians and their metis neighbors had come to rely increasingly on cattle ranching to supplement ‘the hunt.’ Depredations committed in the Walla Walla Valley by the OMV during their advance and in the course of the following winter 8 included confiscation of livestock and food caches of both the Indians and Canadien/metis community. The metis were suspect, and all Indians not in internment camps near the white settlements and forts were assumed to be hostiles. It was an exceptionally cold winter and the O.M.V. received only intermittent supplies. They resorted to living off the land. French Catholic missionary, Father Chirouse, tried his best to mitigate directly with the militia on behalf of his flock, writing letters to the authorities and such, but to little avail. In a convenient leap of logic, all Indian livestock was assumed to have been stolen! And, of course, looting by some of the Indians had been one of the pretexts for the O.M.V.’s invasion of the Walla Walla Valley. Moreover, no one had been killed during this out break of thievery. It is somewhat ironic then, that in addition to all the fatalities, that it was the Oregon militia that proceeded to do a far more thorough job of looting all things in the valley that were edible or of value over the next several months. It would take a long time for the Walla Walla and Cayuse herds to recover. The O.M.V, represented the only force in the field that winter. It was so cold that the Columbia froze over. In mid-March after receiving reinforcements and completing several sweeps north and west along the Snake River the supply situation had become so critical Kelly decided to withdraw the main force. In the meantime, the U.S. Army had finally received reinforcements in January, 1856. Eight companies of the U.S. 9th Infantry arrived under the command of Colonel George Wright. Deployment inland was delayed by weather, and then a major battle fought at les Cascades portage point on the Columbia. In August Fort Simcoe was established by the Army in the Yakima Valley, and in October, 1856 following an attack by Indians on Governor Stevens’ party after the failure of the Second Walla Walla Treaty Council, federal troops under Major Steptoe established Fort Walla Walla. The site of the U.S. Army fort is adjacent to where the modern city of Walla Walla soon sprang up – quickly becoming the largest city in the entire territory of Washington. Having ordered the settlers and miners out of the Columbia Basin, Canadian or American, the U.S. Army was now in place to enforce a truce – one that would last two more years. Then three major battles were fought in 1858 during the May to September time frame which definitively decided the matter. This time it was the U.S. Army with its Nez Perce allies 9 fighting the Spokane, Coeur d’Alene, and again the Palouse. More reservations would be created over the following decades to accommodate these and other tribes in the region, but no longer under the pretense of “treaties.” From here on out Indian reservations would be generated by Executive Orders. U.S. Army Relations with the Militia & Governor Stevens – issues, personalities, and consequences The difficulties faced by the U.S. Army in establishing its authority over territorial militia of Oregon and Washington were considerable. The Pacific Division’s Commanding Officer was General John Wool, who was based out of San Francisco Bay. General Wool had assumed command in 1854 with very few troops at his disposal to cover the entire Pacific coast, let alone inland settlements. With almost a half century of experience on the frontier, General Wool was a prudent, conscientious officer. Richard Kluger the author of “The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek,” characterized General Wool as follows, An old warhorse and a decorated veteran of many a campaign dating back to the war of 1812, Wool strongly disapproved of civilians serving as volunteer soldiers, answerable only to state or territorial authorities who were not professional military men. He considered militia enlistees little better than vigilantes, generally ill-trained and poorly disciplined, who posed a greater threat to the peace than irritable Indians did and often took their empowerment as a license to kill, plunder, and profiteer. As second ranking officer in the U.S. Army, Wool, like his sole superior, General Winfield Scott, had an outsized ego, but was no witless blowhard. Even now, past seventy, Wool maintained his reputation as honest, public-spirited, and highly professional. [Kluger, pp.151-2] The General would soon face a challenge to his authority in the persons of the territorial governors of Oregon and Washington. The Democrats were in the White House and their appointees as territorial governors reflected their populist national agenda including expansion and a particularly harsh approach to race relations - be it blacks back east, or out west, the Indians, mixed-bloods, and now the Chinese immigrants. Once the shooting started in October of 1855, the Washington militia was initially placed under command of U.S. Army, while the 10 much larger Oregon territorial militia never was. Subordination of the Washington volunteers to the Army’s authority would be withdrawn in short order. In the newly created Washington Territory, General Wool faced an ambitious West Point graduate named Isaac Stevens. Two generations separated the much younger Stevens from General Wool. For most of his Army career Stevens had been responsible for building coastal fortifications along the Atlantic. He had met his future wife while building Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island. He had also been in and out of Washington, D.C. during much of his service and had become increasingly engaged in politics. When Franklin Pierce entered the White House in 1853 Stevens successfully sought an appointment. He was not only appointed Governor of the new territory of Washington, but also its Superintendent of Indian Affairs. In addition, while on the way to his new post he would head the northern railway survey. Stevens had the energy and temperament to handle all three positions simultaneously. Kent Richard’s, in his biography of the first of Washington’s many territorial governors, “Isaac I. Stevens: A Young Man in a Hurry,” characterized Stevens’ antagonist, General Wool, and his view of the frontier along these lines, Although he was seventy years old in 1854, Wool remained a vigorous, capable officer – apparently the logical choice for the large politically sensitive Department of the Pacific. He proved to be capable of running the huge department with as much efficiency as circumstances allowed, but he was less suited to handle political problems. Thoroughly professional, completely honest, and imbued with a sense of public service, Wool believed that the Army was in the best position to deal with various problems caused by American expansion. The general would brook no interference from outside sources – which included state, territorial, and local officials within his broadly conceived sphere of influence. ... His critics called him pompous and arrogant. But criticism did not deter Wool. He was not concerned with public relations; he would do his duty as he saw it…. When General Wool arrived at Benecia (on the Sacramento River) to assume command, he was already convinced that Indian hostilities usually resulted from actions by the whites that provoked retaliation. His observations during his first months on the West Coast confirmed that opinion. [Richards, pp. 238-9] Given his character, Governor Isaac Stevens was inclined to move quickly in consolidating the nation’s tenuous hold on its northwest corner. There would be no tolerance for delay in 11 implementing the program. Arriving in the fall of 1853 to assume his responsibilities as the territory’s governor, within 18 months he was leading his small party on a treaty-signing Blitz across the Columbia River basin toward the Rockies. For purposes of economy, to make matters worse, he was under orders form the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to consolidate the widely scattered tribes into a small number of reservations. Resorting to strong-armed tactics to get closure at the Walla Walla Treaty negotiations, the Stevens party immediately moved further inland for the next such event, leaving in their wake numerous resentful Indians. Land was being taken both by the terms of the treaty and, in fact, by settlers, with only promises of eventual compensation. Miners were also on the move with gold discoveries in the Colville Valley drawing them inland. Furthermore, there were no uniformed authorities in sight. The first U.S. Army unit would not show in the Walla Walla valley for another year. In fact, it would be another four years before the treaties would be ratified in 1859. Into this void would move the territorial militia. Meanwhile, in addition to the challenges of removing the surviving Indians from their lands to make way for settlers, this settler community itself was by no means homogenous. A cultural contest continued between the earliest settlers and their missionaries as to national and ethnic loyalties. The missionaries and their flocks were divided roughly along the lines of the competing newer demographic elements – English-speaking American Protestants, now ascendant, versus the older settler group of les Canadiens, who were predominantly Frenchspeaking Catholics. Issues along these lines had involved accusations of Canadian Catholic priests and Canadian mixed-bloods instigating the Whitman Massacre in 1847, resentment over the greater success of the Catholics in converting Indians, and other suspicions that triggered Governor Stevens declaration of Martial Law in the spring of 1856. Martial Law was subsequently overturned in the territorial courts after much public posturing and mutual threats of arrest among the handful of territorial officials - including Stevens’ actual detention of a territorial judge arrested by one of his posses. This was followed by further manipulation of the court system in the prosecution and hanging of Nisqually chief Leschi - an abuse of the process resisted by the Army at Fort Steilacoom to Leschi’s last day on earth. Caught in an uncomfortable position between the Americans on one side, and their Indian in-laws, cousins, 12 neighbors, and friends on the other, most Canadiens felt compelled to pick sides. Others, however, were able to maintain an uneasy neutrality. This posture was totally unacceptable to Governor Stevens and his constituents. In the wake of the Battle of Frenchtown, also known as the battle of Walla Walla, feuding between Governor Stevens and General Wool went public. Wool’s view was that Indian wars were instigated by white miners and settlers, then expanded in scope by their militia. Kurt Nelson, in his book “Fighting for Paradise: A Military History of the Pacific Northwest,” provides us with the following summary of the battle’s origins and consequences. While U.S. Army General John Wool was critical of the Oregon volunteers for widening the war (and mutilating Peo-peo-mox-mox), Washington Territorial Governor Stevens was rich with praise. After attempting to negotiate treaties with other Indians, Stevens arrived in the Walla Walla Valley from the east on December 20, 1855. Governor Stevens was convinced that the Oregon Volunteers had saved his party, as he had heard that the Indians of the area were prepared to ambush him. It was General Wool’s unwillingness to provide an escort for the Governor which led, in part, to the Washington Territorial troops no longer being placed under federal control throughout the rest of the war. Others contended that the Oregon Mounted Volunteers merely expanded the war needlessly. Many Indians had been unwilling to join the Yakimas, until the attack on the seemingly peaceful Cayuse and Walla Walla, which was seen as unprovoked. Further, treatment of Peo-peo-mox-mox, taken under a flag of truce, and then mutilated, was the provocation that sent many tribes, or at least their young men, into the war parties attacking the whites. 13 In the way of further explanation, another quote from Richard Kluger is helpful. In retrospect, Steven’s strategy seems daring and unduly provocative. He was denying the tribes time to let his hard-edged reasoning sink in, likely because he feared they might use a protracted delay to organize coordinated intertribal resistance, uncommon among native peoples, but by no means unthinkable. Stevens was proceeding aggressively, moreover, without military support or the immediate prospect of any. In fact, the U.S. Army commander for the Pacific coast region, General John Wool. … had so few troops at his disposal that he favored a go-slow settlement policy and was outspoken in his belief that white settlers, in their eagerness to displace the natives, were the ones that ignited most of the violence along the frontier. It was precisely this land-hungry breed, of course, who Stevens had been sent west to serve. As he had just done with Leschi [in the southern Puget Sound area] and then at Point Elliot, … the governor would now miscalculate the will of the tribes east of the Cascades to resist him, treaty or no treaty. [Kluger, p.113] With Wool’s prior assessment having been re-confirmed by the Battle of Frenchtown, he also made it clear that he considered the killing and desecration of Chief Peopeo Moxmox to be disgraceful. And of course, Governor Stevens voiced the opposite opinion. Again quoting from Kluger, The governor … continued to believe that the suddenly dire Indian problem was not the result of oppressive and relentless treatymaking on his part, but the tribes’ treachery in forsaking their solemn vows to uphold the written agreements. The problem of low manpower was especially apparent east of the mountains, where Stevens was encamped near Walla Walla on December 28 [18 days after the battle] when he addressed a haughty letter to General Wool, … accusing him of shirking his duty by leaving pacification to “the citizen soldiery [i.e., the volunteer militias] alone to fight the battles and gain the victories.” … Stevens compounded his slur by going on to recommend “that you will urge forward your preparations with all possible dispatch. Get all your disposable force in this valley in January, establish a large depot camp here, occupy Fort Walla Walla and Yakima country, and be ready in February to take the field.” Then, as a civilian territorial official presuming to direct the top U.S. Army officer in their part of the nation, he outlined his own sweeping “plan of campaign” for the Snake River region in eastern Washington Territory. [Kluger pp. 143-4] Stevens was not alone in demanding the Army move aggressively against the Indian population of the region. Stevens reflected the view of many settlers - that the U.S. Army wasn’t doing its job in protecting them from the Indians. In the territory’s capital, Olympia, Washington, the local newspaper, ‘the Pioneer and Democrat’ recorded this increasingly public exchange of recriminations, while putting an extremely partisan Democratic party spin on all news. The newspaper fully supported the conduct of the O.M.V. The Pioneer and Democrat 14 was blatantly pro-Stevens and justified all of his actions and that of the volunteers, with continuing diatribes against General Wool and the U.S. Army. True, insufficient numbers were clearly a problem for the U.S. Army, and territorial volunteers were necessary for defensive purposes to supplement an over-stretched Army. General Wool had been calling for reinforcements from back east, but it took several months for them to be re-deployed to the Pacific. When the volunteers assumed offensive operations, however, they were little more than vigilantes terrorizing the Indians. In addition to unprovoked attacks on Indians that were not hostile, such as occurred with the Oregon Mounted Volunteers at the Battle of Frenchtown, the fact that among their victims there was a significant percentage of children and women was especially appalling – e.g. the Mashel River and Grande Ronde massacres. The latter two massacres were credited to units of the Washington territorial militia. Added to these were the subsequent fatalities caused by drowning while fleeing the attacking militia in panic, or those dying of exposure and hunger following the raids on their villages and food supplies. Continuing with Kluger’s description of the unfolding drama, Arriving at Fort Vancouver in southernmost Washington Territory, he [General Wool] assessed the situation, decided that a winter campaign against the Indians would be disastrous, ordered forts to be built in the Yakima and Walla Walla valleys …. and conveniently forgot to answer the Governor’s earlier letter until February. In his reply, Wool reiterated his outspoken view that Indian misconduct was generally set off by white settlers’ abuses, and in the belief that volunteer militias were prone to turn into unbridled vigilantes eager to bash any redskin within reach, he called for all actions against the Indians to be carried out solely by regular army troops. [Kluger p. 144] In addition to sounding off in ‘The Pioneer and Democrat’ directly or through his friends, Stevens was soon writing Secretary of War Jefferson Davis demanding that General Wool be sacked. Stevens stepped up his effort to vilify General Wool by telling Davis that if the tribes in this region were to be subdued, the War Department had better recognize “the necessity of removing from command of the Department of the Pacific, a man who has by his acts, so far as this territory was concerned, shown an utter incapacity.” [Kluger p.164] 15 Knowing that, in the end, it was likely to be he, Stevens, that would be the one to lose his current job, not the General, Stevens figured that the best way out of the trap was to advance. Time was running out for him due to all the controversy he had stirred up with his outrageous conduct vis-a-vis both the Army and with the territorial courts. Ever popular with the more jingoistic sector of the populace, however, Stevens got himself elected as the territorial delegate to Congress. This gave him the platform in D.C. for pursuing his vendettas, while seeking political cover for salvaging his career. Frenchtown So why was there a Frenchtown at this battle site? Well for starters, as mentioned earlier, most of the French-Canadian West ended up in the U.S. As such, the worlds of the U.S. Army and the Canadians intersected all across the American West. This is clearly not the West in the mind of the general public, which is more geared to Hollywood, and dime-novel distortions. One of the most important members of Lewis & Clark’s Corps of Discovery had been their principal scout, translator and hunter, Georges Drouillard. Then when Astor decided to set up a trading operation near the mouth of the Columbia a few years later, Canadians of French and Scottish origins constituted a major proportion of his employees and partners. Then with Fremont’s expeditions in the 1840s, though Kit Carson got all the press with the American reading public who wanted to hear about one-of-their-own, Fremont’s other principal scout was Basil Lajeunesse. A few years later, in September 1849 Captain William Warner headed up into the mountains of northeastern California from Sacramento to scout the region for 16 alternative trails entering Oregon from the south. And who was beside Capt. Warner when they both went down in a hail of arrows at the head of an Army column? Nobody named Juan or Pedro, but there was a scout named Francois Bercier. As for the mountain range, it was named, of course, for the martyred Captain, not the scout. Likewise, whenever Governor Stevens ventured into the interior, though his trust in them was highly variable, he found himself forced by circumstances into relying on the likes of Pierre Boutineau, Antoine Plante, Andre Dominique Pambrun, and Georges Montour. Following the return of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, it took decades for American settlers to actually start to migrate out to the Pacific Northwest, several more years to establish a new 17 18 border (1846), and then three more years for the first U.S. Army units to arrive in 1849. The latter had in the interim been preoccupied in Mexico and California. The principal public authority in the region during the intervening period had been a British chartered trading monopoly – the Hudson Bay Company (HBC) – responsible for the Western two-thirds of British North America. It was the Hudson’s Bay Company that intervened to save the 56 surviving hostages of the Whitman Massacre in December 1847. There were still no American authorities on hand, and would not be for another 18 months. In fact, it would not be until 1872 that the company and the British Army withdrew from their last enclaves in Washington Territory, where Indians still outnumbered whites till around 1860. The HBC’s current and former employees in the region, mostly of Canadien extraction - along with their mixed-blood families – totaled approximately one thousand people by the early 1840s, as the Americans began to arrive in significant numbers over the Oregon Trail. These former employees had been establishing a series of settlements up river from the company’s various trading posts, receiving various names from the new arrivals, including French Towns, or Prairies, or French Settlement. Though Canadiens in fact - along with their Indian and mixed-blood wives and mixed-blood children – they constituted the majority of settlers in Oregon’s Willamette Valley prior to November 1843 and in Washington Territory until around 1850. Contrary to convenient mythology, most of these people never left the region, though they tended to relocate into the more remote corners of the backcountry over the following decades, many descendants ultimately ending up on several interior Indian Reservations. From the battles of Vincennes (1779), to Detroit (1812), along with an earlier Battle of Frenchtown in Michigan (1813) - on to points west, these Canadien/metis border communities found themselves in the eye of the storm. Lines drawn at tables located on the Atlantic seaboard ignored a less clear-cut reality in the interior. And as their native relations were by no means willing to be passive actors, this multi-cultural people were caught in the middle of the ensuing disturbances. The earlier Battle of Frenchtown fought in southeast Michigan is considered to be the bloodiest single defeat suffered by the Americans during the War of 1812. 19 Along the way, these families, had become the first settlers of the region, usually with smaller scale farming and ranching, often supplementing their income by occasional work as packers, cowhands, ranchers, woodcutters, ferry operators, or toll bridge operators. A significant number were also hired as guides, interpreters, and scouts by the new governmental authorities. Moreover, they did not go away. Washington Territory was not all that different from other areas along the northern borderlands, except as to the particulars. Clearly the hottest, or cutting edge racial issues weren’t what are usually portrayed. Their numbers, their strategic locations, and their skill sets meant that the half-breeds, mostly metis, couldn’t be ignored by the new set of decision makers. As earlier in the century on the frontiers of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, at the time and place they had to be dealt with first - as the original settler group, and necessary intermediaries. This was still Indian Territory. The metis knew the local people and their languages. In Washington, during the 1850s those locals – the Indians - not only constituted a majority of the territory’s population through the end of the decade, but they were the primary source of hired labor, which was still mostly a seasonal requirement. They were also the key to local sources of nourishment. In addition to communication between friends, relations, neighbors or strangers, they knew the terrain. It wasn’t easy to get around without the Indians or metis serving as guides and providing packhorses, ferry services, or canoes. These peoples could be marginalized, then integrated or disposed of later, but for now they were needed. Splitting allegiances down the middle – divide and conquer is usually a good tactic. Many of the descendents of the oldest metis families, though, had already gone the other way, being by then three quarters or even 7/8 Indian, such as the Finleys and the Plantes. Kent Richards, encapsulates the situation at the first meeting of the territorial assembly in 1854 for us. A major issue of the session was the status of the French Canadians formerly employed by the Hudson Bay Company who continued to reside in the territory. Some of the legislators argued that most of the Canadians were pioneers who helped open up the country and who paid taxes. Some citizens petitioned for the denial of voting privileges to anyone who could not read or write English, and, after hot debate, the 20 legislature granted the vote to half-breeds who the election judges determined had adopted the habits of civilization, a compromise that allowed Canadian farmers to vote but excluded those living among the Indians. [Richards p. 188] This story also reminds us of the multiple challenges faced by our predecessors in the mid-19th century in establishing the authority of the Federal Government in this far corner of the world. Americans had arrived late on the scene, and some were inclined to over-compensate for the slow start. As with other matters in life, the establishment of government authority in borderlands, haste often makes waste. Political expediency is no excuse, in military affairs at the time, nor in the later writing of history. (4) The rest of the Story 21 (a) Distilling a New Regional Brew of Metis West of the Rockies This tale covers several generations of mixed-blood or metis families originating with: a father who was Euro-Canadian, Metis (with a Chippewa or Cree admixture), or Iroquois; and with a mother who was either Metis – also from east of the Rockies - or an Indian from one of the Pacific Northwest (PNw) tribes. One way or the other, within a generation, these bi-cultural and multi-lingual people had close relations of blood and friendship with members of the local Indian tribes. Straddling two worlds, the culture of this mixed community was hybrid. No small matter. Their wife’s know-how allowed them to live off the land and their Indian relations brought trade, security, friendship and language instruction. Given their antecedents and the requirements of the place and time, their culture was ‘all of the above’ - a very useful skill set for bridging two worlds still attempting to accommodate each other. Much like the Chinatowns that would soon be cropping up on the edge of Euro-American settlements and mining camps all over the west, the metis settlements were informal affairs. Per earlier mention, they were usually referred to by a generic name, one often associated with ethnicity and language such as French-towns, French Settlements, or Prairies. The ‘Prairies’ included the largest original metis settlement, French Prairie on the middle Willamette, but also Cowlitz Prairie at the head of navigation for the river (and tribe) of that name, or Muck Prairie in the south Puget Sound area. French Prairie proliferated into a set of villages bearing the names of St. Paul, St. Louis, Gervais, Champoeg and Butteville. Other than the French Prairie villages, and Frenchtown on the Clark Fork, few settlements ever retained these names. One in the distant Colville Valley kept an Indian name, Chewelah, but most were sub-planted by names brought in by the later wave of settlers such as Lowden, Toledo, Melrose, or Deere Lodge, or simply translated from the French, such as Kettle Falls. And Fort Vancouver remained Vancouver, along with keeping a share of les Canadiens,’their metis families, living there under the spiritual guidance provided fellow Canadiens including Bishop Augustin M.A. Blanchet, Father Jean-Baptiste Brouillet and the initial establishment of 22 the Sisters of Providence in the West. The latter included the immortalized Mother Joseph. Though the HBC did not originally allow former employees to settle on their own farms near their principal entrepot and plantation at Fort Vancouver, once the U.S. jurisdiction was settled, they could and did make Donation Land Claims around Vancouver much as any other Euro-American settler. A Catholic Church census of their flock had been performed early in 1844, prior to Father Francois Norbert Blanchet’s return to Quebec to become Bishop, and to recruit his younger brother, Augustin Magloire Blanchet. Francois Blanchet then continued on to Europe in order to recruit priests and nuns while raising funds. While there he again advanced in the hierarchy to become Archbishop of history’s least populated archdiocese. The census had placed the number of Indian converts in the Pacific Northwest at 6,000, while les Canadiens and metis parishioners, per earlier mention, were calculated to number roughly one thousand souls. Location of the latter, at that point in time, was divided approximately as follows: about 600 in the French Prairie settlements of the Willamette valley; about 100 each around the Fort Vancouver and Cowlitz Prairie facilities of the Hudson Bay Company, plus another 200 scattered between the interior posts of Forts Colvile, Walla Walla, and Okanogan, plus Fort Langley on the lower Fraser River. There were also smaller establishments on the upper Fraser, as well as along the Pacific coast stretching from Vancouver Island to the Russian Alaskan settlements. An impasse in negotiations between the U.S. and the authorities representing British North America had left the Oregon Country in limbo under ‘joint occupancy’ for three decades. While F. A. Blanchet was in Europe, a treaty finally partitioning the Columbia and Oregon region had been signed. But this was just the beginning of a long process. There was a lot to be sorted out south of the line - one that would exist on paper only for much of the balance of the century. While most Catholic Canadians and their families west of the continental divide remained in the U.S., very few of their descendents stayed in the same locations. People were on the move, and the Catholic Church had some catching up to do. Ditto for U.S. federal government authorities. 23 (b) Working with the New Majority Only months prior to a new Catholic Church census, a major milestone in local demographics and history had been reached. In November 1843 the American Protestant settlers arriving over the Oregon Trail achieved majority status over the earlier Canadiens and metis group in the Willamette valley. With partition of the region two and a half years later in 1846, very few of les Canadiens or metis moved north, the large majority staying put in what was now definitively to become U.S. territory. There would soon be a new set of rules imposed by a new majority. However, the metis were still closely tied to the former majority – the Indians. Fortunately, les Canadiens had acquired significant know-how in the art of accommodating majorities. Furthermore, second-class status here with their lifelong friends and Indian relatives, was better than the third class option available further to the north. The 49th parallel slowly firmed up during a messy transition period from 1846 to 1871, while the Hudson's Bay Company gradually withdrew from their last trading posts in Washington Territory. The small American settler group north of the Columbia in the area that would soon become Washington Territory would achieve parity in numbers with les Canadiens and metis by around 1850. But again, it wouldn’t be until around1860 that the white and metis settler groups combined would outnumber the Natives. When Oregon agreed to the plan to spin off Washington Territory in 1853, it was in order to let the latter serve as the Oregon Country’s Indian Territory, and thereby to facilitate Oregon’s rush to statehood, achieved in 1859 – thirty years before Washington became a state. The final withdrawal of the HBC and the British Army in 1871-2 timeframe would coincide with British Columbia joining the new Canadian Confederation. And fortunately, with the large majority of les Canadiens and metis shorn of with the southern half of Columbia south of the 49th parallel, the northern half retained by Canada could be re-engineered demographically to become an Anglo-Canadian paradise on the Pacific. Lines were starting to coalesce in more ways than one. Property owners among the 24 Canadiens and the first generation of metis had been major beneficiaries of the Oregon Provisional Government, and subsequently, the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850. However, along with a small sprinkling of countrymen of more recent derivation from the British Isles, they soon found themselves engaged as useful, though suspect, intermediaries in all three Indian Wars from 1847 thru 1858, starting with the controversies festering around the Whitman Massacre. They had also been at the center of debates during the first two legislative assemblies of Washington Territory over ethnicity and determination of voting and property rights. And finally, they were the aforementioned targets of Territorial Governor Stevens’ declaration of martial law in the spring of 1856. Facilitating the transition to the new majority might buy them time, but re-integration would present its challenges. [see graphic] (c) “Eastward, Boys, to the Reservation” During the early decades of the 19th century, as mentioned earlier, many of the tribes of the lower and middle Columbia had tribal members who had married les Canadiens and metis from points east. Early alliances and the resultant locale of trading posts meant that some northwest tribes had inter-married with the easterners more than others. Over the second half of the 19th century, a certain number of metis descendents were able to enter the white settler world. This was especially true of metis daughters and grand daughters. Others, however, retreated ever further into the backcountry, forming new communities, or grafting themselves onto the older native communities. For some of the tribes west of les Cascades whose surviving members had a high incidence of inter-marriage with the French-Canadians - such as the Cowlitz, the Chinook/Clatsop and the Cow Creek Band of the Umpqua – reservations were never established. One reason for this was that they had the misfortune of living in what were becoming major thoroughfares or transportation corridors. Like the Spokane and Palouse tribes east of les Cascades, they mostly scattered to reservations set aside for other tribes, or into the deeper recesses of the backcountry. Only those with a head of household who was at least 50% white could stay-put 25 through having obtained – and kept – a donation land claim. Otherwise they soon found themselves guilty of being “trespassers” or tenants on some newcomers land. Unlike their brethren to the west, those tribes east of les Cascades with a significant percentage of intermarriage with les Canadiens did obtain reservations. Tangled up in the tribes’ turmoil and trauma, the net flow of their metis cousins was moving further inland, looking for a refuge. As the frontier settled down and closed up late in the century, it was decided in Washington, D.C. that the recently established Indian reservations suddenly needed to be ‘opened up,’ for further white settlement. Given the alternatives, several of the tribes, as well as the metis, were willing to accommodate. As previously mentioned, a prior generation of metis had gained land ownership through their fathers’ participation in the Oregon Provisional Government, later endorsed under the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850. Now it would be the turn of later generations of metis thru the Dawes Act of 1887 to get another chance at obtaining free land. This time though, between 1885 and 1916, it would have through allotments on the reservation as adopted Indians, not as white settlers. By the early 20th century the largest interior concentrations in the PNW of French-Breeds, as these French-speaking Indians were often called at the time, were found on four reservations. In descending order of numbers, these were the Flathead, Umatilla, Colville, and Coeur d’Alene Reservations. Just after the turn of the century, the number of French-speaking Indians on these four reservations was collectively estimated to have numbered about 1600 people. 26 Included among them were descendents of the Laroque and Tellier families. Joe Laroque’s wife was baptized Lizette Walla Walla, and Louis Tellier’s was called Angelique Pendoreille. By a convenient Catholic practice, Baptismal names for Indian wives included their tribe of origin. Consequently, due to their mother’s origins some Laroque family descendents later received allotments with other Walla Walla tribal members on the Umatilla Reservation, while the Tellier children received allotments on the reservation where the Pend Oreille tribe had relocated, the Flathead Reservation. A similar scenario played itself out for many dozens of other metis families. For example, there were the families of the two senior members of the metis detachment of the Oregon Mounted Volunteers serving as scouts, Narcisse Cornoyer and Antoine Rivet. After the interior of Washington Territory was reopened for settlement in the late 1850s, Narcisse moved with his metis wife Sophie Beleque and their family to the re-established Frenchtown in the Walla Walla Valley, picking a lot on upper Pine Creek. Sophie’s sister, Ester, and her family also joined them taking up farming on Mud Creek just to the northwest of the Cornoyer place. Narcisse then got himself appointed to serve as Superintendent of the Umatilla Indian Reservation between 1871 and 1880. In 1878 he was granted land on the Umatilla reservation when he was adopted, along with another 1/2 dozen members of the metis community as ‘friends of the tribes.’ This also included Andre Dominque Pambrun. The Rivet clan had also trickled inland during this period, leaving French Prairie in the Willamette Valley for the Colville Valley, and ultimately Frenchtown on the Clark Fork and the Flathead Reservation. (d) The Frenchtowns Get Whiter as the Metis Relocate to the Reservations Two of the metis settlements inhabited at some point by a number of these families, actually came to be known as ‘Frenchtown.’ The one in the Walla Walla Valley, we are already familiar with. The other was located on the Clark Fork River (now Montana). Both eventually developed into white communities. The same thing happened to other metis settlements such as kettle Falls and Chewelah in the Colville Valley, or the one that had been centered on 27 Grant’s Ranch near Deer Lodge on the upper Clark Fork. In the end, most of the descendents of the original metis families relocated to the nearby reservations. Follow-on immigration from Canada - or once removed via Minnesota - had allowed one of the Frenchtowns, the one on the Clark Fork of the Columbia, to remain on the map and continue to speak French well into the 20th century. This also occurred in the villages of French Prairie in the Willamette Valley, though here les Canadiens were supplemented by an admixture of French-speakers of European origin from Alsace, Belgium and France. Frenchtown on the Walla Walla, on the other hand received few demographic infusions from these sources after the 1860s. During the late 1880s and early 1890s, most of the earlier metis families had moved from the Walla Walla settlement to the nearby Umatilla Reservation located 30 miles to the southeast. Left behind were a small number of families of Canadien origin – fragments of the Bergevin, Allard, Beauchamp, and Gagnon clans. The inducement of adoption by the relocated Walla Walla tribe, would be a powerful one. It entitled individual members of the metis families to a free allotment of up to 160 acres of land on the upper Umatilla River in the north part of the reservation. Agitation by settlers in the Pendleton area for opening the Umatilla reservation to white settlement had developed into federal government policy. This was embodied in the Slater Bill in 1885 under the sponsorship of one of Oregon’s ‘one term wonders’ in the U.S. Senate. Among the three confederated tribes on the Umatilla, the Walla Walla under chief Homilie willingly served as the adoption agency for the metis. During this turn of the century period the Walla Walla tribe grew from the smallest of the three tribes on the reservation to the largest. This would be undone however in the course of the 20th century as the 1/4 blood quantum rule gradually excluded many of the increasingly diluted descendents. Table 1 Umatilla Reservation census - by tribal group 1876-1906 28 Impact of 1885 Slater Bill opening the reservation to white homesteaders after providing for adoption of mixed-bloods and granting of allotments to each tribal member. Note that virtually all mixed-bloods or ‘metis’ were adopted by one tribe, the Walla Walla whether or not their antecedents were Walla Walla, Cayuse, Cree, or from other tribes. Walla Walla 1876 1888 1898 1903 128 406 529 574 Including 216 MixedBloods Cayuse 385 461 369 385 Including No MixedBloods Umatilla 169 171 188 191 Including 16 MixedBloods An extract of a 1906 BIA report stated, “There were about 1,200 Indians residing on this reservation, of which number about onefourth were of mixt [sic] blood, principally of Canadian-French descent. “ Cheap or free land was getting harder to come by. The growing sense of panic in white 29 settler communities throughout the west had been generated by a sense that the frontier was closing up. This, combined with misdirected philanthropic intentions of Senators back east, led to endorsement a plan similar to the Slater Bill for the entire West. This legislation was enacted two years later in 1887 as the Dawes Act. Over the next three decades, under the provisions of the Dawes Act, a similar fate awaited the Colville, Flathead, Coeur d’Alene and numerous other reservations. At that point it made practical sense for the tribes to dilute the impact of the loss of what little land remained to them to white settlers, by expanding the old practice of adopting close relations from the mixed-blood community. The tribes however were not of one mind on this. The more traditionalist elements within the tribes thought they saw the equivalent of a Trojan Horse at their gates. For the Bureau of Indian Affairs and its Agents, though being likewise of two minds on the matter, and having vacillated over time as to whether to acknowledge or resist the practice of adoption of the metis, the final position was to endorse it. The decision was based on the assumption that the net effect of the presence of mixed-bloods on these reservations would be positive in terms of implementing the government’s dual policy of turning the Indians into both Christians and farmers. The mixed-bloods could serve as useful intermediaries in encouraging the transition of the Indians toward the white man’s goal for them. Table 2 Flathead Reservation 1905 census - ethnic breakdown within each tribe Pend Oreilles (640) - full blood 242 - mixed blood 387 - adopted - 7 Indians and 4 whites; Lower Pend Oreille (197) 30 - full bloods 161 - mixed bloods 35 - adopted – 1 white; Flatheads (557) - full bloods 233 - mixed 305 - adopted - 3 Indians and 16 whites Kutenais (556) - full bloods - mixed 342 - adopted - 2 Indians and 2 whites 210 Spokanes (135) - full bloods 55 - mixed 80 Other tribes (48) - full bloods 14 - mixed 34 Hence the total number of mixed-bloods in 1905 came to 1183 or 55% of the enrollees on the Flathead Reservation. When another wave of Canadiens from the east started to pour into the middle Columbia region at the end of the 19th century, irrigation prospects led them to choose another valley neighboring the Walla Walla to the northwest in the opposite direction from the Umatilla. The chosen valley was the Yakima. Meanwhile the Frenchtown in the Walla Walla Valley had dried up and nearly disappeared. Hence, in the course of the 20 th century, with this turn of the 31 century demographic wave from Canada, supplemented by immigrants from France, the Yakima Valley would end up being the primary and final pocket of Francophones (Frenchspeakers) south of the border in the PNW. The Canadien settlement at Chewelah experienced emigration similar to the two Frenchtowns, with most of the metis population leaving the Colville valley. Most headed east along the Clark Fork, upriver to Flathead country. However, some of the Colville Valley metis relocated to the Coeur d’Alene reservation, while others followed the Colville Reservation’s shifting borders across the Columbia, to the west where it currently resides. Here too, adoption by the Confederated tribes allowed the metis to settle and eventually later obtain an individual allotment of land when the reservations were ‘opened up.’ And as elsewhere, some did stay behind, especially the younger women. As with the Gendron and Finely families, metis daughters had the option of marrying into the new settler community of the Colville valley. Today, south of the 49th parallel, we are faced with an odd statistic that indicates the continental reach of that 14th colony that somehow chose to disengage in 1776. Of the four individuals selected to represent the states of Washington and Oregon in the Capitol Building’s Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C., three were born in Quebec, and two spoke French as their mother tongue. For Washington, along side Calvinist Missionary Marcus Whitman - and providing balance in terms of religion, gender and ethnicity - we have Mother Joseph, born Esther Pariseau from the village of Elzear, just north of Montreal. South of the Columbia we have ‘The Father of Oregon,’ Jean Baptiste McLoughlin, born and raised in Riviere du Loup, paired with Methodist missionary Jason Lee (who, though English speaking, was also from Quebec). Is this sampling an anomaly, or a representative one which indicates a bigger story? Throughout the 19th century, those writing about the American West, be they journalists, or others posing as historians, all shared one overwhelming priority. The story had to be Americanized. 32 The thousands of Francophones of a century ago, now have tens of thousands of descendents in the region. The language is pretty much gone, at least south of the 49 th parallel, but not the people. One way or another, French culture is clearly not foreign in this corner of the continent. This multi-cultural people and their church played major roles during the transition of the northwest frontier. However, re-integration into the world of the new majority – and its history texts - would not be a straight-forward process. Rob Foxcurran Seattle, Washington 206-898-5608 _________________ I’m currently exploring options for publication of my 500-page manuscript on the above subject with the Septentrion publishing house in Quebec, and an affiliate in Montreal, Baraka Books. A Canadian co-author from the University of Northern British Columbia, Michel Bouchard, is working with me to co-author an abbreviated version for the general public. The manuscript is entitled “”Washington Territory's Tale of A Few Frenchtowns: Resettlement of the French-Breeds into the Backcountry and onto the Reservations.” Bibliography Principal Sources for this paper George L. Converse, A Military History of the Columbia Valley: 1848-1865, Pioneer Press Books, Walla Walla, Washington 1988 33 John C. Jackson, Children of the Fur Trade: Forgotten Metis of the Pacific Northwest, Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, Montana 1996 John C. Jackson, A Little War of Destiny: The Yakima Walla Walla Indian War of 1855-56, Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, Washington 1996 Richard Kluger, Seizing Destiny: How America Grew From Sea to Shining Sea, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 2007 Richard Kluger, The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek: A Tragic Clash between White and Native America, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 2011 Harriet Duncan Munnick and Adrian R Munnick, translation and editing, The Catholic Church Records of the Pacific Northwest: St. Ann, Walla Walla, Frenchtown, Binford & Mort Publishers, Portland, Or. 1989 Kurt R. Nelson, Kurt R. Fighting for Paradise: A Military History of the Pacific Northwest, Westholme Publishing, Pennsylvannia 2007 Steve Plucker, Battle of Frenchtown manuscript, 2011, unpublished Kent Richards, Isaac Stevens: Young Man in a Hurry, Washington State University Press 1993 U.S. National Archives, Federal Records Center, Seattle, Washington: - Bureau of Indian Affairs Files for the Umatilla and Flathead Reservations; - U.S. Census for Washington and Montana Territories: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880 Union-Bulletin, Walla Walla (newspaper) 34 “Canadians and French Played Major Part in Valley’s Development,” April 10, 1927 “The Frenchtown Story: Community, Not a Town,” page 30, August 27, 1967 “French-Breeds, “ pages 32-3, June 11, 1978 “Rendezvous planned to commemorate ‘French Town,’” June 20, 1993 R.R. Foxcurran, unpublished papers: (1) French-Canadians in the American West, 2000, (2) Washington’s Canadians in the 2nd half of the 19th Century, 2003 (3) Washington Territory’s Tale of a Few Frenchtowns: relocation into the backcountry and onto the reservations (2010) Sampling of other sources for full bibliography of 500-page manuscript Jean Barman and Bruce M. Watson, "Fort Colville's Fur Trade Families and the Dynamics of Race in the Pacific Northwest," Pacific Northwest Quarterly Summer 1999, a quarterly publication of the University of Washington Ray Allen Billington, The Far Western Frontier: 1830 -1860, Harper & Row, New York 1956 Carpenter, Cecilia Svinth, Fort Nisqually: A Documented History of Indian and British Interaction, Published by Tahoma Research Service 1986 David C. Courchane, Jocko’s People: The Descendents of James Finlay and His Son, Jacques Rafael Finlay , privately published 1997 Nicolas de Finiel, An Account of Upper Louisiana, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 1989 Maurice Denuziere, Je Te Nomme Louisiane, Editons Denoel, Paris 1990 35 Steven B. Emerson, “Oregon volunteers battle the Walla Wallas and other tribes beginning on December 7, 1855,” HistoryLink.org, April 20, 2008 Eugene Mark Felsman, “Brief History of the Enrollment Process on the Flathead Reservation, Montana, 1903-1908,” unpublished paper presented for a Contemporary Issues course, at the Salish and Kootenai College, to instructor Ron Therriault, March 2, 1991 Martha Harroun Foster, We Know Who We Are: Metis Identity in a Montana Community, University of Oklahoma Press: Norman 2006 Frenchtown Historical Society, Frenchtown Valley Footprints, Mountian Press Printing, Missoula, Montana 1976 James R. Gibson, Farming the Frontier: The Agricultural Opening of the Oregon Country 1786 -1846, University of Washington Press, 1985 George and Terry Goulet, The Metis in British Columbia: From Fur Trade Outposts to Colony, Fabjob Inc., Calgary Alberta 2008 Gilles Havard, Empire et Metissages: Indiens et Francais dans le Pays d’en Haut 1660-1715, Septentrion, Presses de l’Universite de Paris-Sorbonne 2003 Gilles Havard and Cecile Vidal, Histoire de L’Amerique Francaise, Editions Flammarion, 2003 36 Alexander Harmon, Indians in the Making: Ethnic Relations and Indian Identities around Puget Sound, Univ. of California Press 1998 Ingersoll, Thomas N., To Intermix with our White Brothers: Indian Mixed Bloods in the United States from Earliest Times to the Indian Removals, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque 2005 Irwin, Judith W., "The Dispossessed: The Cowlitz Tribe Continues its 140 year Struggle for Recognition and Restitution," Columbia Summer 1994 [a quarterly publication of the Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma, Wash.] John C. Jackson, “Old Rivet,” Columbia Magazine, Summer 2004: Vol. 18, No. 2 John C. Jackson, “The Man Hunter: George Drouillard,” We Proceeded On (magazine of the Lewis and Clark Heritage Foundation) , February 2009, Vol. 35, No.1 Jacques Lacoursiere, Jean Provencher, and Denis Vaugeois, Canada-Quebec:1534-2000, Septentrion, Quebec 2001 Lavender, David, Bent's Fort, University of Nebraska press, Lincoln 1954 Lavender, David, Fort Vancouver and the Pacific Northwest, [Part II of Handbook No.113 entitled, Fort Vancouver], National Parks Service Publications Division, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. 1981 37 Lavender, David, Land of Giants: The Drive to the Pacific Northwest 1750-1950, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln & London 1956 Raymonde Litalien, Jean-Francois Palomino, Denis Vaugeois, La Mesure d’un Continent: At;as Historique de l’Amerique du Nord: 1492-1814, Septentrion, Quebec Lokken, Roy N., “The Martial Law Controversy in Washington Territory: 1856,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, April 1952 Dean Louder & Eric Wadell, Du Continent Perdu a L’Archipel Retrouve: Le Quebec et L’Ameriique francaise, Les presses de l’Universite Laval, Quebec, Canada 2007 Dean Louder & Eric Wadell, Franco-Amerique, Septentrion, Quebec, Canada 2007 Grant MacEwan, Les Franco-Canadians dans l'Ouest, Editions des Plaines, Saint-Boniface Manitoba 1986 Mackie, Richard Somerset, Trading beyond the Mountains; The British Fur Trade on the Pacific, University of British Columbia (UBC) Press 199 Miller, Jay, Mourning Dove: A Salishan Biography, University of Nebraska Press, Linclon and London 1990 Nisbet, Jack, Visible Bones, Sasquatch Books, Seattle 2003 38 Nisbet, Jack, Mapmaker’s Eye: David Thompson on the Columbia Plateau , Washington State University Press, Pullman,Washington 2005 Peltier, Jerome, Antoine Plante, Ye Galleon press Fairfield, Washington, 1983 Peterson, Jacqueline, and Brown, Jennifer S. H.., The New Peoples: Being and Becoming Metis in North America, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1984 Wilson, Roy I., The Catholic Ladder and Native American Legends – A Comparative Study, Publisher, Roy I. Wilson, Bremerton Washington, 1996 Ruby, Robert H., and Brown, John A., Indians of the Pacific Northwest: A History, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1982 Wlifred P. Schoenberg, [University of Gonzaga historian], A History of the Catholic Church in the PNW:1743-1983, The Pastoral Press, Washington, D.C., 1987 Smith, Burton M., "The Politics of Allotment on the Flathead Indian Reservation," originally published in the Pacific Northwest Quarterly, vol 70, no.3 July 1979) pp. 131-40. New edition copyright 1995 for Salish and Kootenai Papers, Published by the Salish and Kootenai College Press, Pablo Montana, 1995 Spokane Review, “Down in Wallula 74 years Ago,” October 2, 1904 James G. Swan, The Northwest Coast, or Three Years in Washington Territory, 39 University of Washington Press (originally published in 1857) Tamastslikt Cultural Institute Archives, Umatilla Reservation, Pendleton, Oregon Wade Thomson, Descendents of the Fur Trade: Morigeau, Finley, Berland, Couture Families , Copyright Oct 2005, Wade Thomson Clifford E.Trafzer, and Richard D Scheuerman,. Renagade Tribe: The Palouse Indians and the Invasion of the Inland Pacific Northwest, Washington State University Press, Pullman Washington 1986 Vaugeois, Denis, America: L’Expedition de Lewis & Clark et la Naissance d’une Nouvelle Puissance 1803-1853, Les Editions du Septentrion, 2002 Sillery (Quebec) Bruce M. Watson, Lives Lived West of the Divide; A Biographical Dictionary of Fur Traders Working West of the Rockies, 1793- 1858, Centre for Social, Spatial, and Economic Justice, University of British Columbia, Kelowna, B.C. 2010 Whealdon, Bon I., edited by Robert Bigart, I Will Be Meat For My Salish, Salish Kootenai College Press, Pablo, Montana, and Montana Historical Society press, Helena Mont, 2001 40 41