Chapter 4: General Issues in Research Design

Background

Causation, units, and time are key elements in planning an research study.

Causation is the focus of explanatory research. At the outset, it’s important to keep in mind that cause in social science is inherently probabilistic . Certain criteria must be satisfied before it can be inferred that something causes something else. The text refers to the discussion of idiographic and nomothetic modes of explanation considered in Chapter 1. There are both necessary and sufficient causes. A necessary cause is a condition that, by and large, must be present for the effect to follow. A sufficient cause is a condition that more or less guarantees the effect in question. There are molar and micromediational causal statements. Both can be useful in criminal justice research.

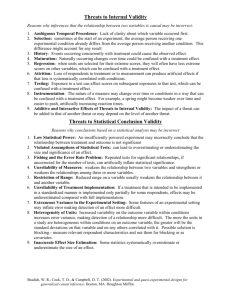

Scientists assess the truth of statements about cause by considering threats to validity. When we are concerned with whether we are correct in inferring that a cause produced some effect, we are concerned with the validity of causal inference. The next concern is a number of different validity threats in causal inference – reasons we might be incorrect in stating that some cause produced some effect. Statistical conclusion validity refers to our ability to determine whether a change in the suspected cause is statistically associated with a change in the suspected effect.

Internal validity threats challenge causal statements that are based on some observed relationship. Construct validity refers to generalizing from what we observe and measure to the real-world things in which we are interested. External validity is concerned with whether research findings from one study can be reproduced in another study, often under different conditions. The four types of validity threats can be grouped into two categories: bias and generalizability. Internal and statistical conclusion validity threats are related to systematic and nonsystematic bias, respectively.

Scientific realism bridges idiographic and nomothetic approaches to explanation by seeking to understand how causal mechanisms operate in specific contexts .

Units of analysis and the time dimension are two key elements in planning a research study.

In criminal justice research, there is a great deal of variation in what or who is studied – the units of analysis . Units of analysis are typically also the units of observation. Among the most common units of analysis are:

individuals – Any variety of individuals may be the units of analysis in criminal justice research

groups – Social groups may be the units of analysis in criminal justice research.

organizations – Formal political or social organizations may be the units of analysis in criminal justice research

social artifacts – Social artifacts are the products of social beings and their behavior.

1

There are two very important concepts that are related to units of analysis:

The ecological fallacy refers to the danger of making assertions about individuals as the unity of analysis based on the examination of groups or other aggregations.

Reductionism is an overly strict limitation on the kinds of concepts and variables to be considered as causes in explaining the broad range of human behavior represented by crime and criminal justice policy.

Because time order is a requirement for causal inferences, the time dimension of research requires careful planning. Time-related options for research designs offer choices that are particularly important for exploratory studies. Exploratory and descriptive studies are often cross-sectional . The problem with this design is that conclusions are based on observations made at only one time. Other research projects, called longitudinal studies , are designed to permit observations over an extended period. Three special types of longitudinal studies should be noted:

Trend studies look at changes within some general population over time.

Cohort studies examine more specific populations as they change over time.

Panel studies are similar to trend and cohort studies except that the same set of people is interviewed two or more times.

It may be possible to draw approximate conclusions about processes that take place over time even when only cross-sectional data are available.

Retrospective research asks people to recall their pasts, and is another common way of approximating observations over time. On the other hand, a prospective approach follows subjects forward in time

Designing research requires planning several stages, but the stages do not always occur in the same sequence. A schematic view of the social science research process is provided in Chapter 4

(Figure 4.2). Here is a “quick” rendition of the sequence:

<B>Conceptualization

→

Choice of Research Method →

Operationalization → Population and Sampling →

Observations →

Data Processing → Analysis → Application</B>

The Research Proposal

Here are the key elements of a research proposal:

Problem or objective

Literature review

2

Subjects for Study

Measurement

Data-Collection Methods

Analysis

Schedule

Budget

3