App3.2_eco_random_AS

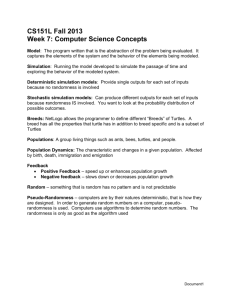

advertisement

PROTOTYPE (1/9/04): ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FOR DELIVERABLE 1.1.2 (TO INFORM DISCUSSION AT LISBON PROJECT MEETING 19/9/04) Activity Sequence: Modelling in Ecoliteracy & Randomness Aims of activity sequence This activity sequence is the result of merging two existing ones: Ecoliteracy and Randomness. The focus is on collaboration and modelling, with the provision of joint activities, common tool kits and a weblabspaedia site. 1. Ecoliteracy The goal of this activity sequence is to learn concepts and techniques of modelling and how to construct dynamic systems on a computer. This activity sequence has evolved from previously focussing on learning about ecological and complex systems to focus now on modelling and construction of dynamic systems. Ecological and complex systems still play an important role in the activity sequence since these serve the role of providing domains with properties that are interesting to construct computational models of. As application domains they also provide a means of fostering collaboration between children in the different sites of the project. The activity sequence is designed to provide tools that let children learn to model – and also construct their own – dynamic representations of real world phenomena. The sequence aims to provide means for children to control some of the expressive properties of computation and at the same time get insights into how a complex phenomena in the real world can be expressed through computer modelling in different forms. The domain holds properties that we find particularly interesting for the purpose of the project. The modelling, construction, exchange, and modification of dynamic systems provide new means for children to communicate with each other, even though they are not able to understand each others’ spoken and written languages. One challenge that has emerged during the second year of the project has been that of achieving the kind of collaboration between children across sites that fosters the knowledge building processes that the project has set as one of as its central goals. Simply finding technical solutions for how to manage translation of children’s webreports will not be sufficient in reaching this goal. Especially since the project has set out to also provide children with other than pure language based means of communicating their knowledge. When developing the activity sequence we presupposed that animals, nature and environmental issues would be topics that many children at this age are interested in, and also that the geographical differences between the sites in the project would make it particularly interesting for students to exchange models were such issues were central aspects. DraftAS Eco-modelling/Randomness 1 of 9 Moreover, another goal of the Weblabs project is to explore how transparent modules of programming code or more generally, computational processes, could be used for modelling and programming activities in order to express and communicate ideas within particular knowledge domains. Behaviours of – and relations between – organisms are aspects that we find to be very well suited for the exploration of such programming structures while also being interesting and engaging for the targeted age group. 2. Randomness What is randomness? What is a random phenomenon? Given a phenomenon how can we judge if it is random or not? These questions are still open in the sense that there is not yet a universally accepted definition of randomness. Probability (in which we include the concept of randomness) is a quite young subject; in fact historians chose 1654 as a convenient landmark for the birth of mathematical probability, due to the contents of the correspondence of Pascal and Fermat regarding games of chance. Furthermore its first universally accepted axiomatisation was proposed by Kolmogorov in 1933. However, humans have been coping with randomness for thousands of years, for instance in chance games, thus it is only its mathematical interpretations that are relatively new. Drawing from history, the peculiarity of mathematical formalizations of randomness is that they are based either on common sense, either on key ideas derived from different scientific contexts. In fact we can find interpretations, and related attempts of formalizations, of the word “random” for instance as: “unpredictable”, “lawless”, “incomputable”, “uncompressible”, “not deterministic”, etc. Any of such characterisation can be ascribed to the idea of randomness, and contributed to define its key aspects, as shown by the historical evolution of the definitions of randomness. Our activity sequence relies on the idea of building meanings for some of the key words associated to randomness, taking into account of issues highlighted by research in mathematics education such as: 1. cultural biases concerning randomness (for instance in Lotto games, people’s belief that the less a numbers is extracted, the more chances to be extracted it has); 2. gap between intuitions and probabilistic formalizations; 3. difficulties in gathering together different random related experiences; literature shows examples of pupils being able to cope with different random phenomenon, but being unable to individuate a common denominator linking the different experiences. The activity sequence that we designed, approaches the idea of randomness on the one hand by exploring some key dichotomies such as “predictability vs. unpredictability”, “presence of pattern vs. lack of pattern”, “rule based vs. not rule based”, “fairness vs. unfairness”, “determinism vs. indeterminism”; on the other hand some key properties of randomness are explored, such as the properties of random walk, and independence of events from events’ history, etc.. The study of such dichotomies, and properties, is to be DraftAS Eco-modelling/Randomness 2 of 9 intended as a means to explore and define the dichotomy “random vs. non-random”, which is the core of our educational goal. An additional goal of the randomness activity is a qualitative understanding of some aspects of probability such as sample space and law of large numbers: Probability at school is usually introduced via sample activities with coins, dices or spinners. RCXLego tangibles might provide another set of tools that augment physical devices with computational power and link them to the computer based ones. Constructing and using tangible random devices offers an opportunity to make pupils experience concepts of randomness and probability starting from their intuitions. It also allows us to discuss interesting advanced concepts, such as the verification of a random source and the properties of random walks. To support the related activities we will introduce modelling of LEGO robots and other phenomena focusing on random strategy and modification and/or replacement of the random generator used into the model. Role of collaboration Within the development of the proposed activities, collaboration between the participants concerns pedagogical, cultural and source related aspects that we will discuss partially in this section. Other detail will be given along activities descriptions. In the following we are going to describe, in general lines, how collaboration shell be set up in standard school situations, where we have a teacher and a group of pupils. Such general lines, with slight changes, apply to any situation characterized by a group of learners and one person (or a few) orchestrating their activities; thus they apply to any of the specific settings within the project. Collaboration will occur at the following levels: Group work: within a single class collaboration will happen within subjects participating to activities with different and well defined roles. For instance in some cases some pupils will be involved in the production of a phenomenon, while others will participate as active observers (making conjectures, taking notes, etc.). Webreports: among different classes, participants may collaborate communicating both as single persons and as whole classes via web tools. Group work Collaboration within single classes will happen both in the form of small group of pupils activities and in the form of class discussion under the guidance of the teacher. The aim of the former is to stimulate each pupils’ verbalization, and reciprocal help, concerning what is being observed and done during the development of the activity. On the other hand the aim of the latter is both, to compare and socialize the outcomes of the small groups’ works, and to stimulate individuals’ further advances and inquires. Here it is part of the teacher’s role to let emerge pupils’ intuitions and guide them toward the focusing on, and the command of, some key aspects of the considered knowledge domain (randomness in this case). In particular the teacher may act as: concepts’ mediator that pupils are not able to construct neither individually nor in collaboration; DraftAS Eco-modelling/Randomness 3 of 9 provocative agent of the emergence of new concepts; mediator for making new concepts explicit. Pupils will be required to produce both reports of what they will have individually done, and reports of what they will have learnt through collective activities. We hypothesize that pupil will learn to better express themselves, and to improve their capability to talk about meaningful contents. On the basis of the mentioned reports, the class as a whole (teacher and pupils) will produce a “group webreport” which will represent the status and the evolution of the knowledge which is shared within the class. The activity of producing such individual reports, and collective notebook, together with its extension to a larger community, pupils will be introduced to a meaningful cultural experience; namely the process of knowledge sharing, which is a fundamental step in the construction of adults’ scientific knowledge. Weblabspaedia In order to orchestrate the process of knowledge sharing, pupils within the different sites will be involved in the production of a common “Weblabspaedia”, where the concepts of the activity will be explored in terms of significant examples, words, ideas, and sayings. Each class (or local group of pupils), will be involved in the production of a local “collective notebook”, which will be published on the web (perhaps with researchers’ technical help), written in the pupils’ mother tongue. Such documents will represent the cultures of each local group. Concerning the languages to be used to write both the local documents and the common “Weblabspaedia”, firstly we need a language which is powerful as an expressive tool and as a tool for thinking, for each pupil to approach new concepts. Secondly, we need a common language to share knowledge across sites. Finally we want each group to be integrated, with its culture, in the community with equal importance and dignity. Therefore the common “Weblabspaedia” will be written in English, whilst the local “collective notebooks” will be written in native languages, which are more familiar to the single groups. Thanks to a common language, and several native languages, we plan to exploit linguistic and cultural differences as a propellant for the evolution of common activities. Given their collective notebooks, local groups will be required to choose some of their contents to be proposed to the other groups as “candidates” for the edition of the common Weblabspaedia. This step will require: choice of contents to be shared production of a document containing such contents (for all groups); and translation of such documents in English (for all non-native English speakers). We will call such documents “proposal documents”. Although a common language is chosen, it may be the case that different groups will give different meanings to the same words, thus we will foster a process of comparison which will be orchestrated by teachers (or researchers) in order to reach agreements on the possible meanings of each word. Starting from the proposal documents, local and cross sites debates will be set up, in order to choose what of the proposed contents will be included in the official “common Weblabspaedia”. Along with such debate the Weblabspaedia will be edited, possibly with researchers’ technical help. DraftAS Eco-modelling/Randomness 4 of 9 In the case of randomness, at the core of the designed activities, there are some key words and sayings (see aims in this document), and the exploration of their meanings. This exploration is rooted in pupils’ cultures, and in the specific practical experience proposed. This approach is supported by the literature review, with particular attention to the cultural historical evolution of the meaning of randomness. We choose the metaphor of the Weblabspaedia, as a cultural instrument that, for each item, may contain a wide variety of relevant material that represent the cultural meaning of the item. The contents of our Weblabspaedia, for each item, will contain key words, sayings, examples, questions, relevant problems, etc.. We believe that, the cultural diversity of the groups will bring to each item different elements that, shared within the community, will enrich the shared meanings of to the item. Each element used to describe en item, will be considered an items itself and will have its dedicated documents. For each of these items there will be a dedicated web document. The single pages will evolve along with the sequence of activities. In particular, for each item of the Weblabspaedia, we will have as many proposal documents and local Weblabspaedia items, as the number of the involved groups. To conclude, the main idea is that of setting up an activity of collaboration, which goes through the whole duration of the experimentation and that unifies all participants under a common aim, the construction of a Weblabspaedia. Furthermore, the Weblabspaedia will function also a means for sharing experiences and knowledge. Thus, in case pupils will be involved in different practical activities, they will have a chance to learn from what others will have been doing. Models An important part of the collaboration in this activity sequence should evolve around the models that the children construct (models created on the computer as well as on paper). The most important reason for this is that it is the actual artefacts that are an expression of the children’s understanding of the phenomena under study. By allowing children to try out, change, and extend each other’s models, they are allowed to investigate different ways of understanding and expressing knowledge. In addition, collaboration through model exchange provides a way of overcoming the language barrier between children in different countries. Assessment criteria In our view the assessment of the students’ learning should be conducted within a “situated” framework where assessment is integrated with the students’ daily and weekly learning activities. This is especially important in tool-intense activities where learning cannot be separated from the use of the involved tools. Therefore we will focus the assessment around the character of the models that children create and the way they talk about their models, as they construct them and explain their workings to each other in the weekly sessions. In order to find indications of how the children’s understandings develop throughout their work we will compare their models and explanations at different stages in the activity sequence. Hence, we will not create particular assessment activities, DraftAS Eco-modelling/Randomness 5 of 9 for instance, in the form of pre- and post-tests, since we find that these run the risk of getting detached from the children’s actual learning activities and thereby not measuring what actually is intended. We will use student’s models and conversations, field notes and video recordings as the main data sources. In the analysis these will be used in the following way: Researchers field notes and reflective reports These will serve as reflective material for the researchers to develop rich descriptions of the aspects that are focused upon in the students’ models and conversations. Students’ models The content and functionality of the students’ models will be analysed. The analysis will cover the dynamics of the model, how real world phenomena are represented, how relations and dependencies between species are represented, how behaviours are defined, etc. Analysing students’ webreports and weblabspaedia Analysing how characteristics of the students’ models are described and discussed in reports and weblabspaedia, Students’ conversations Higher level analysis of students’ conversation and argumentation will investigate what the students focus upon, e.g. dynamics, function, looks, etc. Video recordings This will be used to conduct detailed analysis and zoom into particular issues found in the analysis of conversations and models. As collaboration is a central element in the children’s activities we will need to assess both individual and collaborative learning. Most data collected will be based on the children’s collaborative activities, especially since they will not be working with individual projects but mostly in pairs or in groups. Moreover, all activities will be conducted in collaborative settings with children and teachers working together. Hence, we will initially take a collaborative point of view with respect to assessment, and as the analysis evolves search for indications and evidence of learning at the individual level. Tools The following tables lists all the tools current available on the WebReports site for randomness. Tool Random jump ToonTalk Sweeper Bot (Random Bot 2D) Description Behaviour that moves jumping randomly around. A vehicle that moves in a 2D area and sweeps balls away, or DraftAS Eco-modelling/Randomness Type Animation tool Animation tool 6 of 9 Stream bar graph Stream counter Remove duplicates Nest to box Box to nest Random gardens tools Coin disintegrates them. Plots a bar graph of the elements of a stream Counts how many times an object is present in a stream Removes all duplicated elements of a box. Converts a stack of objects on a nest into a box. Converts a box of objects into a stack on top of a nest. ToonTalks tools for exploring random numbers generators. coin you can toss by hitting t Destructive random garden Picks at random one of the parts (i.e. pictures, texts and numbers) of the white picture. Random Garden Picks at random one of the parts (i.e. pictures, texts and numbers) of the green picture. ToonaTalk Shaker It is a tool that can contain one or more balls, when it is shaked, the balls begins moving, bouncing on the sides of the shaker, and slowing down according to a predefined friction Bounce Random Garden Extracts an element from its contents whenever it is touched by another ToonTalk object. Copy touched this little gadget sends a copy of whatever it touches to a nest. Data Analysis tool Data Analysis tool Generic tool Generic tool Generic tool Notebook Random Generator Random Generator Random Generator Random Generator Random Generator Random Generator Table 1. List of Randomness Toon Talk tools. Tool The Random Bot 2D (Sweeper Bot) ShakerHarvester The RandomBot1D (Drunk Bot 1D) ShakerBot Description Description and building instructions of the Random Bot 2D also called Drunk Bot 2D or "Berto" (as pupils of Class2A suggested) Description of the RCX tool ShakerHarvester, with images, instructions, and NQC file. Description of the RandomBot1D with instructions for building and running it. ShakerBot RCX Robot Table 2. List of RCX tools. DraftAS Eco-modelling/Randomness 7 of 9 Tool Description Used in Defined in Ecoliteracy1.tt Example simulation where not all objects are programmed. Random motion A new behaviour for random movement. Ecoliteracy1.tt Systems TM spec Move with arrows A new behaviour for moving with arrows. Ecoliteracy1.tt Systems TM spec Dive Object make a “dive” at regular intervals. Behaviour consist of sub behaviours - Start dive - Turn at bottom - Stop dive Ecoliteracy1.tt Systems TM spec Eat Object "eats" food-object Ecoliteracy1.tt upon collision. Consist of sub behaviours: - grow when touching - remove objects collided with Systems TM spec Starve Keeps making the object smaller and smaller (starving). Contains subbehaviours: - Shrink sometimes - Starve to death Ecoliteracy1.tt Systems TM spec Grow when touching User defines the amount with which the object grows when touching the specified object. Eat (Ecoliteracy1.tt) Systems TM spec Shrink sometimes Uses the tool - seconds counter Starve (Ecoliteracy1.tt) Systems TM spec Starve (Ecoliteracy1.tt) Systems TM spec Starve to death If width or height is smaller than zero, the whole object is removed from memory. Subbehaviours: - remove when width=0 DraftAS Eco-modelling/Randomness 8 of 9 Tool Description - Used in Defined in remove when height=0 Remove objects collided with Transfers the behaviour of Eat (Ecoliteracy1.tt) removing oneself to the object colliding with. Systems TM spec Seconds counter Repeats counting seconds Shrink sometimes from a number that users (Starve) define down to zero. Dive Systems TM spec Behaviour cards Playing-style cards representing the animal gadgets Role playing activities Table 3. List of Toon Talk Ecoliteracy tools. The merging of the tools from the two activities implies modifying the movement behaviours in the animal gadget to decouple the random generator from the actual update of the position and velocity of an object. Furthermore, by enabling some behaviours (e.g. eat) to be executed in a probabilistic fashion (by including a random garden as a trigger) will make possible to explore random strategies in the ecoliteracy domain as well. Overview of activity sequence The merge of the activity sequence will be based on a spiral approach where key concepts are visited more times from a variety of point of views. Here we outline the joint planned activities; for what concerns the other activities in the specific domains (ecoliteracy, randomness) we refer to the existing documents detailing them. We will start by introducing ToonTalk via the animal gadgets for example exploring last year children models (see: Our new animal gadget webreport) and building new ones. Some children would then continue on the ecomodelling parts (e.g. Sweden) while others might focus on Randomness for example modelling the behaviour of LEGO robots such as the shakerbot or the sweeperbot (by the way the two model share the same LEGO vehicle, the random generator is different). The exchange and collaborative development of models will be based on the “guess and modify my model” activity were children will examine a model constructed using the animal gadget’s toolkit and modify it introducing non-determinism. To provide a common language to discuss the randomness aspect of children model we will jointly organize a guess my garden activity. At the end of each of those activities the classes involved in the field-testing will update a common weblabspaedia. DraftAS Eco-modelling/Randomness 9 of 9