Travel book (July 07) - University of Sheffield

advertisement

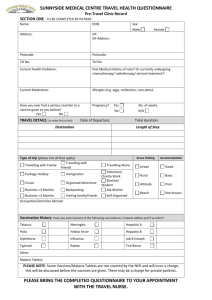

53, Gell Street Sheffield S3 7QP Tel: 0114 2222100 Results & Advice Line: 0114 2222111 Term Time: 1-2pm Results of Tests, 2-3pm Advice Vacation Time: 2-3pm Results & Advice STUDENT TRAVEL INFORMATION AND ADVICE CONTENTS British vaccination schedule International Schedules for travel vaccines General side effects of vaccines Malaria Sun safety Accident prevention Medical advice on diving problems Winter sports injuries First Aid Kits Culture shock Advice for travelling in remote areas Insurance cover Food and water advice Swimming Diarrhoea Hepatitis B and HIV infection Insect bites Animal bites Advice for women travellers Contraception advice for travellers Advice on air travel: dehydration, circulation problems, jet lag Airline flight restrictions Fear of flying, air rage Altitude sickness, mountain sickness Ear care and air travel Appendices – diseases that can be vaccinated against in the traveller List of travel clinics in the UK Travel Health books – general reading list References British Vaccination Schedule Recommended age Which vaccine is given of vaccination 2 months old Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough) polio and Hib Meningitis C 3 months old Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough) polio and Hib Meningitis C 4 months old Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough) polio and Hib Meningitis C 13 months old MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) 4-5 years old (pre- Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and polio school) MMR booster 13-18 years old Tetanus, diphtheria and polio Ref: 1 NB: It’s particularly important to check that your MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) immunisation is up to date because some teenagers have not had two doses of MMR. MMR was introduced into the UK vaccine schedule in 1988 with a second dose being introduced in 1996. So, if you were born before 1992, you have probably only had one dose of MMR. So, if you think this applies to you, you should book an appointment for the second dose now. If you have never had the MMR vaccine, you should have one dose now and another three months later. Meningitis C vaccine was introduced into the UK vaccine schedule in 1999. It is recommended that if you did not receive 3 doses as a small baby within the above schedule, that you have received 1 dose to protect you against this disease. It is still very important to be aware of the signs and symptoms of meningitis, as the vaccine does not protect against other strains. Hib (Haemophilus influenzae) was introduced into the UK vaccine schedule in 1993. Hib vaccine is only recommended for the age group 2mths – 10yrs. BCG (Tuberculosis) vaccine recommendations changed in the UK in July 2005. You may well have already received a BCG vaccine between the ages of 10yrs-14yrs. Only one vaccine is recommended. The new UK government guidelines are: all babies living in areas where the incidence of TB is 40/100,000 or greater babies whose parents or grandparents have lived in a country with a TB prevalence of 40/100,000 or higher unvaccinated new immigrants from countries with a high TB prevalence Ref: 1 Why do we need immunisation? The UK national immunisation programme has meant that dangerous diseases such as tetanus, diphtheria and polio have effectively disappeared in the UK. But these diseases could come back – they are still around in many countries throughout the world. That’s why it’s so important for you to protect yourself. I don’t remember what vaccines I’ve previously had, how do I find out? Your parents may remember. Your family GP may have records. Your medical records may have the information. Your school may have records of vaccines given at school. It is always worth you having your own personal record of what immunisations you have had, in case records aren’t available. International Schedules for travel vaccines NB: If you have had all 5 childhood doses of: Diphtheria, Tetanus and Polio, then you are protected from these diseases for life in countries where the diseases have effectively disappeared. But when travelling to countries where the diseases are still endemic, it may be recommended that you receive a booster within the last 10years. Ref: 2 International Schedules for travel vaccines Vaccine Dose 1 Dose 2 Dose 3 Dose 4 Booster Doses Hepatitis A Day 0 6months – 10-20 years (Should be given at 12months (dependent on least 2weeks manufacturer) before departure) Typhoid Day 0 3 yearly if still (Should be given at at risk least 2weeks before departure) Hepatitis B – Day 0 1 month 6 months Day 0 1 month 2 months 5 years (preferable schedule) Hepatitis B – (accelerated Day 0 Day 7 Day 21 (very rapid 12 5 years months schedule) Combined 5 years months schedule) Hepatitis B – 12 Day 0 1 month 6 months Hepatitis A at Hepatitis A & least 10 B years. (Twinrix) Hepatitis B (preferable 5 years schedule) NB Twinrix does NOT have an accelerated schedule like Hepatitis B. Combined Day 0 Day 7 Hepatitis A & Day 21 12 Hepatitis A at months least 10 B years. (Twinrix) Hepatitis B (very rapid 5 years schedule) Yellow Fever Day 0 (must be given at least 10 days before 10 years (if still at risk) entering country & a certificate issued) Men ACWY Day 0 5 years. (Haj (should be given at pilgrims may least 2-3 weeks need after 3 years before departure) – please get up to date advice) Rabies Day 0 Day 7 Day 21-28 2-5 years (if still at risk) Japenese B Day 0 Day 7-14 Day 28 12 Encephalitis months (Green Cross) (if still at Tick Borne risk) Day 0 Preferably 1- 9-12 months 3 years Encephalitis 3 months after 2nd dose at risk) (FSME) after 1st dose (if still (but if travelling immediately day 14) Please Note: Children’s Vaccine doses and schedules are very different, so please ask your nurse specifically about these. WHAT GENERAL SIDE EFFECTS OF VACCINES CAN YOU EXPECT TO EXPERIENCE? Some people will develop slight tenderness, redness and sometimes swelling at the site of the injection and a small number may experience slight fever, headache, general aching and malaise approximately 24 hours after the vaccination, lasting for up to 24 hours. You are advised to take regular analgaesia to reduce your temperature (e.g paracetamol) and to drink plenty of non alcoholic fluids. A cold compress applied to the site of the injection may relieve the discomfort. WE DO REQUEST YOU WAIT IN THE WAITING ROOM OF THE SURGERY FOR APPROXIMATELY 20-30 MINUTES AFTER RECEIVING ANY VACCINES. This is merely a precaution, because in extremely rare circumstances, a person can have an immediate and sometimes severe allergic reaction which would require medical attention. SPECIFIC INFORMATION ABOUT YELLOW FEVER VACCINE The symptoms described above under general side effects can sometimes occur in yellow fever vaccine 5-10 days after vaccination. If you are concerned about your condition, you can telephone the University Health Service Advice Line (details front cover) and ask to speak to a nurse or doctor. If the surgery has closed, you can also phone NHS Direct on: 0845 4647 for 24 hr help and advice from a nurse or doctor. MALARIA Malaria infects over 500 million people worldwide, causes over one million deaths each year and threatens the lives of about 40% of the world’s population. All it takes is one bite from an infected mosquito for this to happen to you. Many people do not realise how dangerous malaria can be, or that in some cases it can lead to kidney failure, seizures, coma or even death. Find out about the real dangers of malaria and speak to your doctor about malaria prevention before you travel. There are different options available and one will suit you. The Dangers: Malaria is preventable and treatable and yet it remains one of the major causes of death worldwide Malaria is an infectious disease caused by the Plasmodium parasite It is carried from person to person by infected female Anopheles mosquitoes How Malaria Spreads: Infected mosquito bites a human Parasite rapidly goes to liver within 30 minutes The parasite starts reproducing rapidly in liver. Some parasites lie dormant in the liver and become activated years after initial infections. Gets into the blood stream, attaches and enters red blood cells. Further reproduction occurs. Infected red blood cells burst, infecting other blood cells. This repeating cycle depletes the body of oxygen and also causes fever. The cycle coincides with malaria’s fever and chills. After release, a dormant version of malaria travels through the host’s blood stream, waiting to be ingested by another mosquito to carry it to a new host. Protecting Yourself From Malaria ABCD A – BE AWARE OF THE RISK OF MALARIA All travellers to malarious areas must be aware of the risk of malaria in the places they visit B – PREVENT OR AVOID BITES FROM THE INFECTED MOSQUITO Use mosquito repellent with DEET (diethyltoluamide) on both your skin and clothes. Keep arms, legs and feet covered and, if possible, with light coloured clothing C – COMPLY WITH THE APPROPRIATE CHEMOPROPHYLACTIC DRUGS (PREVENTATIVE MEDICATION) There are different antimalarial options and one will suit you, so speak to your healthcare professional about the best protection for you D – PROMPT DIAGNOSIS FOLLOWING ANY SYMPTOMS OF MALARIA (EG FLU-LIKE SYMPTOMS) AND OBTAIN TREATMENT IMMEDIATELY The main initial symptoms are often mistaken for flu and include headache, vomiting, fatigue, nausea, muscular pains, mild diarrhoea and fever. Did you know that…………… the most lethal form of malaria is on the increase the signs of malaria can often be confused with flu malaria can live inside you for years and can be a long-term disease malaria is not a seasonal disease and you are at risk of it throughout the year it is not only in dirty swampy areas that you can contract malaria you are not necessarily safe from malaria if you stay in big cities or four star hotels you are at risk by travelling to malarious areas without taking antimalarials it is important to complete the antimalarial course after returning from holiday you should ideally seek advice on malarial eight weeks before you travel but can still seek advice even at the last minute there are antimalarial medications available to suit your individual needs (Ref: Malaria Hotspots. GSK. 05/04) Visit www.malariahotspots.co.uk to find out more……… DIFFERENT TYPES OF MALARIA There are 4 different species of human parasite: Plasmodium falciparum (most serious) in sub-Sarahan Africa, Papua New Guinea and Amazon rain forests of South America – death can occur within days Plasmodium vivax in Indian sub-continent P.Ovale mostly in Africa P.Malariae mostly in Africa Signs and Symptoms Illness usually begins within 2-4 weeks of the infected bite. But sometimes up to 35 days Malaise, headache and muscle pains but the first major symptom is usually fever. At this stage symptoms are similar to flu. Rigors followed by profuse sweating occur. A wide range of other symptoms can occur including diarrhoea, abdominal pain and a dry cough. Anti-malarial medication Your nurse/doctor will advise which tablets you should take. Medication How long Whilst in the How long after before malarious departing entering area malarious area? malarious area? Chloroquine Commence 1 week Every week whilst 4 weeks after departing (Adults) 300mg before entering in malarious area malarious area to be taken malarious area weekly Proguanil Commence 1wk Every day whilst in 4 weeks after departing (Adults) 200mg before entering malarious area malarious area to be taken daily malarious area Mefloquine Commence 2-3 weeks Every week whilst 4 weeks after departing (Adults) 250mg before entering in malarious area malarious area to be taken malarious area Every day whilst in 7 days after departing malarious area malarious area weekly Malarone Commence 1-2 days (Adults) x1 tablet before entering to be taken daily malarious area Doxycycline Commence 1-2 days Every day whilst in 4 weeks after departing (Adults) 100mg before entering malarious area malarious area to be taken daily malarious area SUN SAFETY Sun damage to the skin Although sunbathing may be enjoyable, it must be remembered that excessive sun exposure is a health hazard due to the effect of ultraviolet radiation on the skin. Ultraviolet A (UVA) and Ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation are known to cause premature cancers. UVB also causes sunburn. This is more likely when the light is also ‘reflected’ from water (swimming pools or the sea), white sand or snow. Vulnerable groups These groups may be more likely to get sun burn problems than others • Babies and children. • Fair skinned people who often also have red hair or blue eyes. • Those with certain medical conditions such as albinism or previous skin cancer. • Those on certain medications such as tetracyclines or diuretics. General Precautions • Babies under 9 months should be kept out of direct sunlight. • Children should wear long sleeved, loose fitting shirts, hats and highfactor waterproof sunscreen. • Everyone should avoid the midday sun, usually from noon until 14.00 hours (15.00 in tropical regions). • Adults should wear a broad brimmed hat, long sleeved shirts and sunglasses. Sunscreens • These absorb ultraviolet B (UVB) and to a lesser extent ultraviolet A (UVA). • The Sun Protection Factor (SPF) refers to the protection against UVB. (e.g. ‘SPF 8’ allows approximately 8 times longer sun exposure without burning than with no protection). • There is a voluntary star system denoting UVA protection; more stars indicating greater protection. Also check for any expiry dates Sunburn and heat-stroke cause serious problems in travellers. Both are preventable - to avoid, use the following PRECAUTIONARY GUIDELINES • Increase sun exposure gradually, 20 minutes limit initially. • Use sun blocks of appropriate adequate ‘SPF’ strength. Re-apply often and always after swimming and washing. Read manufacturer instructions. HOW TO BE SUNSMART Sunscreen does not offer total protection from the suns rays and using it is only one way to reduce your risk of skin cancer. Be SunSmart * Stay in the shade between 11am and 3pm The sun is most dangerous in the middle of the day – find shade under umbrellas, trees, canopies or indoors. * Make sure you never burn Sunburn can double your risk of skin cancer * Always cover up Sunscreen is not enough – wear a t-shirt, a wide brimmed hat and wraparound sunglasses (eyes get sun damaged too) * Remember to take extra care with children Young skin is delicate, keep babies out of the sun completely * Then use factor 15 sunscreen or higher Apply sunscreen generously 15-30 minutes before you go outside (it doesn’t work immediately), and re-apply often Also…. report mole changes or unusual skin growths promptly to your doctor avoid using sun beds or tanning lamps Ref: 3 ACCIDENT PREVENTION All travellers should have health insurance to cover accidents as well as other illness and check that repatriation in an emergency is also covered. General advice • Be aware of the possible risks and avoiding predictable injury should always be the first priority. • Foot injuries on the beach, for example, are common in those not wearing shoes. • Unfamiliar sea creatures (e.g. fish or molluscs) and caterpillars may be unexpectedly venomous. • Dogs in many countries run wild and will respond aggressively when approached. • Skin injuries can lead to tetanus and 10 yearly boosters of tetanus toxoid are advised when post-exposure tetanus hyperimmune immunoglobulin may not be available. • Serious injuries that may need blood transfusion can be of concern where HIV screening of blood products is not universal. • To reduce any risk of mugging travel in groups, avoid remote areas after dark, use a torch, keep on the move, carry an alarm or an anti-personnel spray (may be illegal in some countries), wear modest clothing – do not display wealth. Road accidents • When crossing the road remember the traffic may come from the opposite direction to the one in your home country. • Drivers in some countries may not observe pedestrian crossings or traffic signals. • Strictly observe speed limits, traffic lights and signs. • Never drink and drive. • Consider locking your doors at stopping points. e.g. at night in isolated areas. • Be very careful on potholed and non-tarmacadamed ‘dust’ roads which can become corrugated from continual exposure to the wind. • Think twice about taking an overloaded up-country bus. • Scooters and motor bicycles are frequently unstable on poorly maintained roads and those riding have very little protection in the event of an accident. • Check hire vehicles very carefully for mechanical defects. Swimming and diving • Alcohol and swimming do not mix. • Do not swim immediately after a big meal – cramp may be more common. • Low water temperature can induce hypothermia. This can be rapidly fatal – within minutes. Both the sea and inland deep water lakes may be very cold even during hot summer months. • Sunburn is common and may be unexpected since the swimmer is kept cool by being in the water. • Beware of fast moving tides and currents, especially the undertow from waves and in deep water – even strong swimmers may find it difficult to get back to the shore. • Avoid swimming alone. • Swim in approved places when there is a beach patrol or lifeguard service. • Avoid using airbeds or inflatable dinghies in the sea. If there is an offshore wind they can easily been blown a long distance off shore. If this happens the scenario is often panic, jumping off, exhaustion and hypothermia. Invariably it is better to stay ‘aboard’, try to attract attention and await rescue. Medical Advice on Diving Problems The Royal Navy provides a 24 hour emergency advice service. This gives information on the location of your nearest medical diving problem treatment facility (recompression chamber) and the emergency management of diving related illness. Tel:- 07831 151 523 (cell phone) or 0831 151 523 (non cellphone) and ask for the Royal Navy Duty Diving Medical Officer. State clearly that there is a diving problem. In case of difficulty an alternative contact is Royal Hospital, Haslar. Tel:- 023 92 584255 Winter Sports Injuries • Do not be over ambitious – make sure you are fully trained for the degree of skill required. • Avoid excessive fatigue – accidents often occur before lunch and on the way back to the resort in the evening. • Keep up your carbohydrate and fluid intake. • Become familiar with the terrain and the hazards involved, including avalanche potential. • Watch out for other skiers and snowboarders. It is your responsibility to avoid skiers in front of you. • Observe adverse weather warnings. • Do not ‘economise’ on protective clothing, boots and safety equipment. • Consider helmets for younger skiers and snowboarders. • Learn to fall correctly and to release your ski stick before it damages your thumb (skiers thumb)! FIRST AID KITS o Back packers in particular, should consider including something for simple diarrhoea, sufficient anti-malarial tablets, possibly an antibiotic (discuss this with the nurse), and emergency malarial treatment if going to areas remote from medical facilities. o The University Health Service sells Merlin Medical Packs (for use by qualified medical staff in an emergency). This pack should be carried in countries where sterile emergency equipment may not be readily available. CULTURE SHOCK o This can be very real. Family or social difficulties at home and psychological problems, including alcoholism, make adapting difficult. Time differences between continents might increase isolation when it is difficult to maintain contact with friends and relatives. A situation that is exciting and welcome to one person can be daunting to another. o Problems may include adjusting to a different climate and language, unfamiliar social amenities, coming to terms with poverty, begging and movement restrictions for safety or political reasons. The extent of difficulties will vary between individuals, but being open to new and different cultures and being patient, rather than critical, will help you adapt to new and challenging adventures. ADVICE FOR TRAVELLING IN REMOTE AREAS If you intend to take part in an expedition, or if you will be travelling in areas where help is difficult to obtain in an emergency, you may find it useful to consider the issues discussed below. You should be aware that travel in areas which are remote from medical facilities involves an additional element of risk. In the event of a serious injury or illness it could be many hours or even days before evacuation is possible. You should consider the characteristics of the environment you will be in, such as altitude, extremes of temperature and weather, distance from outside help, and how these factors may affect the ease of rescue in the event of an emergency. Depending on whether you are with a commercial trek, a youth expedition, travelling independently or in some other group, the provision for medical support can vary enormously. Some groups always have a doctor with them, others may have a nurse, paramedic or first-aider. You should ensure in any case that someone has thought about medical issues and that an appropriate first aid kit is carried. Preferably everyone on the trip should have a basic knowledge of what to do in an emergency. It would be advisable to get training in first aid before departure; courses are available which are aimed specifically at those travelling in remote areas. It is worth taking a small personal first aid kit in addition to the main expedition kit. Before departure The best way to deal with medical problems is to prevent them happening in the first place. This is even more important if you are going somewhere where medical support is hard to obtain. It would be a good idea to have a medical check-up before going, and remember to take supplies of any medications which you commonly need. A dental check-up is especially important, and should be done at least three months before departure to give time for any necessary work. Tell your dentist that you will be going on expedition and for how long, and he may elect to fix small problems earlier rather than later in order to avoid potential complications in the middle of the jungle. If you usually wear contact lenses, consider whether you will be able to keep them in a sterile condition when away. Often in an expedition environment this is not possible, and it may be wise to use spectacles instead. Contact lenses can also be a problem if the environment is dusty, such as a desert. Physical and mental fitness Most expeditions are likely to involve a considerable amount of physical exertion. It is very much worth preparing for this with a regular aerobic exercise programme, for several weeks or months before departure. This will certainly increase your enjoyment of the trip and improve the chances of achieving your objectives. Some people may find it difficult adapting mentally to an expedition environment, due to factors such as a lack of privacy and being cut off from family and friends. If you have a history of any psychological problems, including alcoholism or drug dependency, it is important to make sure that these are well under control before putting yourself into an unfamiliar environment. It may be worth seeking counselling before your plans are finalised. The extent of difficulties will vary between individuals, but being open to new and different cultures and being patient, rather than critical, will help you adapt to new and challenging adventures. Camp hygiene Depending on whether food is provided by your own expedition, or bought locally, the risks of infection will vary. If local cooks are employed, check that they use hygienic methods to avoid contamination. You will usually need to treat drinking water by chemical means and/or filtration. Sterilised water should also be used for cleaning teeth and for washing dishes and cutlery. All expeditions should have an environmentally aware policy about the disposal of kitchen and human waste, which should be kept totally separate from cooking areas and water sources. Wash your hands, with water containing a disinfectant, before eating or handling food and always after using the toilet. INSURANCE COVER Take out adequate insurance cover for your trip. This should possibly include medical repatriation and this is extremely expensive. If you have any pre-existing medical conditions, make sure you inform the insurance company of these details and check the small print of the policy thoroughly. If you travel to a European Union country, make sure you have obtained an E111 form before you travel (including a photocopy of the original form). The E111 form is in the T6 leaflet, and after completion, should be stamped at the Post Office. WATER Diseases can be caught from drinking contaminated water, or swimming in it. Unless you KNOW the water supply is safe where you are staying, ONLY USE (in order of preference) 1. Boiled water 2. Bottled water or canned drinks 3. Water treated by a sterilising agent. This includes ICE CUBES in drinks and water for CLEANING YOUR TEETH. SWIMMING It is safer to swim in water that is well chlorinated. If you are travelling to Africa, South America or some parts of the Caribbean, AVOID SWIMMING in fresh water LAKES and STREAMS. You can catch a parasitic disease called SCHISTOSOMIASIS from such places. This disease is also known as BILHARZIA. It is wise NEVER TO GO BAREFOOT, but to wear protective footwear when out, even on the beach. Other diseases can be caught from sand and soil, particularly wet soil. FOOD Contaminated food is the commonest source of many diseases abroad. You can help prevent it by following these guidelines • ONLY EAT WELL COOKED FRESH FOOD • AVOID LEFTOVERS and REHEATED FOODS • ENSURE MEAT IS THOROUGHLY COOKED • EAT COOKED VEGETABLES, AVOID SALADS • ONLY EAT FRUIT YOU CAN PEEL • NEVER DRINK UNPASTEURISED MILK • AVOID ICE-CREAM and SHELLFISH • AVOID BUYING FOOD FROM STREET VENDOR’S STALLS Another source of calories is ALCOHOL ! If you drink to excess, alcohol could lead you to become carefree and ignore these precautions. Two phrases to help you remember 1. COOK IT, PEEL IT, OR LEAVE IT! 2. WHEN IN DOUBT, LEAVE IT OUT! PERSONAL HYGIENE Many diseases are transmitted by what is known as the ‘faecal-oral’ route. To help prevent this, always wash your hands with soap and clean water after going to the toilet, before eating and before handling food. TRAVELLERS’ DIARRHOEA This the MOST COMMON ILLNESS that you will be exposed to abroad and there is NO VACCINE AGAINST IT! Travellers’ diarrhoea is caused by eating and/or drinking food and water contaminated by bacteria, viruses or parasites. Risk of illness is higher in some countries than others. High risk areas include North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian Subcontinent, S.E. Asia, South America, Mexico and the Middle East. Medium risk areas include the northern Mediterranean, Canary Islands and the Caribbean Islands. Low risk areas include North America, Western Europe and Australia. You can certainly help PREVENT travellers’ diarrhoea in the way you BEHAVE - make sure you follow the food, water and personal hygiene guidelines already given. Travellers’ diarrhoea is 4 or more loose stools in a 24 hour period often accompanied by stomach pain, cramps and vomiting. It usually lasts 2-4 days and whilst it is not a life threatening illness, it can disrupt your trip for several days. The main danger of the illness is DEHYDRATION, and this, if very severe, can kill if it is not treated. TREATMENT is therefore REHYDRATION. In severe cases and particularly in young children and the elderly, commercially prepared re-hydration solution is extremely useful. This can be bought in tablet or sachet form at a chemist shop. There is now a new formula containing rice powder which also helps to relieve the diarrhoea, particularly useful in children. Prepare the re-hydration solutions according to instructions. ANTI DIARRHOEAL TABLETS can be used for adults but should NEVER be USED in children under 4 years of age, and only on prescription for children aged 4 to 12 years. A wide range of products are available over the counter at chemist shops. None of these tablets should ever be used if the person has a temperature or blood in the stool. DO CONTACT MEDICAL HELP IF THE AFFECTED PERSON HAS:• A temperature • Blood in the diarrhoea • Diarrhoea for more than 48 hours (or 24 hours in children) • Becomes confused In very special circumstances, antibiotics are used for diarrhoea, but this decision should only be made by a doctor. (A woman taking the oral contraceptive pill may not have full contraceptive protection if she has had diarrhoea and vomiting. Extra precautions must be used - refer to your ‘pill’ information leaflet. If using condoms, use products with the British Kite Mark.) HEPATITIS B and HIV INFECTION These diseases can be transmitted by 1. Blood transfusion 2. Medical procedures with non sterile equipment 3. Sharing of needles (e.g. tattooing, body piercing, acupuncture and drug abuse) 4. Sexual contact. (Sexually transmitted diseases may also be a risk) ways to protect yourself • Only accept a blood transfusion when essential • If travelling to a developing country, take a sterile medical kit • Avoid procedures e.g. ear, body piercing, tattooing and acupuncture • Avoid casual sex, especially without using condoms REMEMBER - excessive alcohol can make you carefree and lead you to take risks you otherwise would not consider. INSECT BITES Mosquitoes, certain types of flies, ticks and bugs can cause many different diseases. e.g. malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever. Some bite at night, but some during daytime. AVOID BEING BITTEN BY: • Covering up skin as much as possible if going out at night, (mosquitoes that transmit malaria bite from dusk until dawn). Wear light coloured clothes, long sleeves, trousers or long skirts. • Use insect repellents (containing DEET or eucalyptus oil base) on exposed skin, clothes can be sprayed with repellents too. Impregnated wrist and ankle bands are also available. Check suitability for children on the individual products. • If room is not air conditioned, but screened, close shutters early evening and spray room with knockdown insecticide spray. In malarious regions, if camping, or sleeping in unprotected accommodation, always sleep under an mosquito net (impregnated with permethrin). Avoid camping near areas of stagnant water, these are common breeding areas for mosquitoes etc. • Electric insecticide vaporisers are very effective as long as there are no power failures! • Electric buzzers, garlic and vitamin B are ineffective. ANIMAL BITES Rabies is present in many parts of the world. If rabies is not treated, death is 100% certain. There are 3 RULES REGARDING RABIES 1. Do not touch any animal, even dogs and cats 2. If you are licked on broken skin or bitten in a country which has rabies, wash the wound thoroughly with soap and running water for 5 minutes. 3. Seek medical advice IMMEDIATELY, even if you have been previously immunised. ACCIDENTS Major leading causes of death in travellers are due to swimming and traffic accidents. You can help prevent them by taking the following PRECAUTIONARY GUIDELINES • Avoid alcohol and food before swimming • Never dive into water where the depth is uncertain • Only swim in safe water, check currents, sharks, jellyfish etc. • Avoid alcohol when driving, especially at night • Avoid hiring motorcycles and mopeds • If hiring a car, rent a large one if possible, ensure the tyres, brakes and seat belts are in good condition • Use reliable taxi firms, know where emergency facilities are. ADVICE FOR WOMEN TRAVELLERS Contrary to popular opinion, world travel and exploration have never been the sole prerogative of man. However, women have additional problems to overcome as a result of their physiology and gender. Menstruation Emotional upset, exhaustion and travelling through different time zones can all contribute to an upset in the menstrual pattern. Irregular menstruation is a very common problem affecting women travellers, excessive exercise and the stress of travel may cause infrequent periods, if this is the case it may lead to confusion over the timing of oral contraception and great anxiety of unplanned pregnancy. Dysmenorrhoea may also be aggravated by travel. Oral contraception can be used to suppress menstruation This is achieved by taking the pill continuously, without the usual seven-day break in between packets. A reminder to take extra packets to allow for this should be stressed. However, this method is not advisable for women taking biphasic or triphasic pills because the dose in the first seven pills is too low to prevent possible breakthrough bleeding.( See Nurse/Dr for further advice if necessary or ring advice line.). Menstruation can also be suppressed using Norethisterone tablets (a progesterone drug). An appointment with a Doctor is required to receive advice on this drug. Sanitary hygiene Tampons and sanitary towels are unobtainable in parts of Africa, Asia and South America, and they are scarce luxuries in many of the former eastern block countries. Locally made menstrual supplies are usually available although the standard varies. Travelling women should be sensitive to the cultural and religious attitudes towards menstruation. In some countries it is forbidden to enter places of worship while menstruating and some cultures will not allow women to touch or even walk near food. To avoid such situations discreet use of and disposal of sanitary towels and tampons would be advisable. Personal safety and security When travelling, particularly alone, leave an itinerary of your trip with a responsible person contacting them at pre-arranged times and dates. Ostentatious displays of money, jewellery, luggage and dress can encourage the wrong type of attention. When travelling be aware of where your luggage, particularly hand bags, are at all times. Do not leave them unattended or hanging on the back of chairs in restaurants. Choose your accommodation carefully:• try and pick accommodation which is in a safe area i.e. not bang in the middle of the local red light district, • request a room near the lift or stair well, • not on the ground floor, • inspect the door locks and window fasteners, • never open the door to your room until you have identified the caller, • do not identify yourself on the telephone until the caller has done so, • keep your money and valuables close by you at night. Be alert, listen to the advice of locals and fellow travellers, develop a street sense, try not to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. In a confrontational situation a woman traveller is rarely a physical match for a man. The following rules can help: • Don’t turn a scary situation into a dangerous one if you can help it (e.g. it would be unwise to launch into a physical attack if the man confronting you is just after your money – hand it over and avoid finding out what he may do if provoked). • Don’t panic or show fear or let the person confronting you get the upper hand, try to gain psychological advantage throwing him off his balance i.e. compliance. • If you do find yourself in physical dangers try to anticipate the aggressor’s next move and plan ahead for it. As the innocent party in the confrontation you have the advantage of surprise, if you are forced to strike back physically, make sure it is a crippling blow that gives you a chance to escape. • If you are worried about your ability to gauge dangerous situations and to defend yourself then consider joining a women’s self defence course before travelling. Personal safety when travelling alone Insist on inspecting your accommodation before agreeing to stay. If unhappy with the room request a change or where possible move to different accommodation. The lone woman traveller will often be flouting convention simply by her presence. Unfortunately women in the developing world don’t have the independence that their western counterparts take for granted. For this reason, their presence, especially unaccompanied, will generate interest within local people of both genders. Male dominated Muslim countries such as the Middle East, North Africa, Pakistan and parts of India and South America are frequently seen as difficult places for women to visit. How you dress is an easy method of self-preservation and the most immediate symbol of respect. Dress codes differ greatly from country to country and to get them wrong would put you at an immediate disadvantage. A culture’s standard of dress has a lot to do with what parts of the body are considered to be sensuous or provocative. As a general rule tight and skimpy clothes are inappropriate for most countries outside of Europe and North America. Clothing should be conservative and presentable, loose fitting and comfortable. Arms and legs should be covered, especially when visiting places of worship and national monuments. Throughout the Arab world and in other Muslim countries, hair should be covered by a head scarf. When travelling try to be inconspicuous yet confident avoiding confrontational challenging situations with men by adopting an assertive, dismissive manner. Remember many men can see eye contact as a ‘come-on’. The use of dark sunglasses will limit this problem. Be prepared to answer questions about yourself particularly if single and travelling alone. The often-asked questions of your marital status and family, are ones of genuine interest. To avoid the unwanted attentions of some men the use of a few white lies about ‘your husband’ and a fake wedding ring are a useful pretence. (Adapted from ‘Travel Medicine and Migrant Health’ – chapter on Women and Children by Marlene Simpson.) CONTRACEPTION ADVICE FOR TRAVELLERS Women travelling or living for prolonged periods abroad should be advised to find out what contraceptive services are available to them in the country/countries they are visiting. The International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) and the Family Planning Association of Britain can provide extra information. The Combined Oral Contraceptive Pill Stomach upsets and severe diarrhoea reduce absorption and may leave inadequate protection. If vomiting occurs within three hours of taking the Pill a barrier method should be used as well, throughout the stomach upset and for seven days after it has ended i.e. ‘the seven day rule’. Some broad-spectrum antibiotics, e.g. doxycycline, may reduce their efficacy. (This normally only occurs for the first 3 weeks of taking doxycycline.) The Family Planning Association advice is that additional contraceptive precautions should be taken whilst on a short course of broad-spectrum antibiotics and for 7 days after stopping. The Progestogen only Pill (POP) For women taking the progestrogen only Pill the same rules apply as with the combined Pill. It is slightly less effective, 96–98%, and must be taken at the same time each day – this can pose problems when crossing time zones. However, it does have the advantage of not being affected by antibiotics. Injectable methods of contraception (Parenteral progestogen– only contraceptives) Injectable contraception is not affected by time zones, gastrointestinal upsets and antibiotics. Condoms Reliable condoms are often hard to find in the poorer parts of the world. If the condoms carry the British Kite Mark or the new European CE mark it means that they have been tested to a strict safety standard. Rubber perishes with age, and heat, and should be discarded if it displays any signs of being brittle, sticky or discoloured. Diaphragms/caps They should be stored in a cool dry place in an airtight container, severe heat can perish rubber. Spermicides may loose their efficacy if not stored in cool, dry containers. Creams may melt and be difficult to apply and pessaries, which are designed to melt at body temperature, impossible to use. (Adapted from ‘Travel Medicine and Migrant Health’ – chapter on Women and Children by Marlene Simpson.) Advice on air travel (health issues) Dehydration The circulating air in aircraft cabins is kept dry to protect equipment and this can mean passengers may become significantly dehydrated. Alcohol can make this problem worse. Drinking adequate fluids (sufficient to keep the urine pale) is necessary and skin moisturisers can help dry skin. Circulation problems Sitting still for long periods in the inevitably cramped positions in aircraft frequently leads to swollen ankles and sometimes muscle cramps. Venous thrombosis in the legs and occasionally serious pulmonary emboli can occur – some authorities suggest that the anti-adhesive effect of a small dose of aspirin on blood platelets may be helpful in those predisposed such as the elderly, the overweight, those with heart problems and those on oral contraceptives. Regular stretching and mobility exercises should be encouraged and walking around the cabin whenever practicable. Use of surgical support stockings may be beneficial. It is however, important that they are correctly fitted. Jet lag Changes to circadian rhythms These regulate our sleep patterns, need time to adjust to changes in local time (usually about one day per time zone crossed). Westward travel may be better tolerated than eastward travel but problems occur when travelling in both directions. The effects of jet lag include – sleep disturbance, loss of appetite, nausea and sometimes vomiting, bowel changes (e.g. constipation), general malaise, tiredness and poor concentration. • A relaxed flight is important. • Avoid travelling when you are already tired and take rest before departure. • Remember the actual home to destination travelling time will usually be at least twice the actual time spent in the air since it will include waiting in airports and often unexpected delays. • Breaking very long journeys halfway with a stopover can be helpful. • On the flight get maximum sleep aided by a mild hypnotic if necessary. • Stretch and exercise as much as possible to aid circulation and prevent swollen ankles. • Drink plenty of water or soft drinks to counteract the dry cabin atmosphere and remember alcohol in spirits and wine and also caffeine increase dehydration (caffeine is present in coffee, tea, chocolate and cola). Jet lag is made worse by a hangover! • Avoid heavy commitments on the first day. Be prepared for tiredness in the evenings and early waking which can last up to 5 or more days. • Hypnotics (sleeping tablets) have been shown to help sleep and correspondingly alertness during the following day. They do not speed up adjustment the new time zone and therefore may need to be used for several nights. • Some travellers find taking regular melatonin helpful. It may help the body to adjust its circadian rhythms but its effect is scientifically unproven. It is not readily available in Britain but can be purchased in some other countries such as USA and Hong Kong. Infections on air flight Respiratory tract infections There is no convincing evidence that re-circulation of air in aircraft cabins increases the risk of transmitting infections since very effective filters are used to remove bacteria and viruses. However sitting in close proximity for long periods next to passengers who are suffering, for example, from common colds or influenza clearly may increase the chances of a passenger becoming infected. This is why airlines discourage passengers from travelling while unwell with infectious conditions. Tuberculosis The World Health Organization (WHO) advises that, with tuberculosis increasing worldwide, there is a small but real risk of catching the disease during air flights. Transmission has only been recorded in flights lasting over eight hours. The risk is clearly greater when many of those on board are from countries with a high incidence of the disease. Parasitic infections Occasionally head lice and other skin parasites have been passed through contact with aircraft seats when a previous passenger has been infested. Itching and a papularrash, for example, around the neck and occiput can result. Airline flight restrictions Airlines may discourage or not allow passengers with the following conditions to fly. • Pregnancy beyond 36 weeks. • Neonates during the first few days after birth (longer after premature births). • Recent or current middle ear infections or sinusitis. • Unstable psychiatric illness. • Unstable epilepsy. • Previously documented air rage or a record of previously causing disruption during flights (some airlines use a ‘yellow card’ warning system). • Recent myocardial infarction. • Moderate/severe heart failure. • Moderate/severe hypoxic pulmonary disease. • Recent chest, intracranial or abdominal surgery. • Recent pneumothorax. • The presence of a communicable disease. Airlines’ regulations may vary so if in doubt advice should be sought from the medical department of the airline concerned. Fear of flying In Britain an estimated nine million people suffer anxiety about flying and may miss out on professional and personal opportunities. There is no single personality-type prone to fear of flying and there may be a link with problems at work or home. Fear may develop from a bad experience – a rough flight, or after a news report of a highjacking or crash. Panic attacks are common (sudden, intense anxiety, sweating and trembling). The sensation is often so frightening that the sufferer may from then on refuse to fly. Advice for the traveller who is afraid of flying. • Explain that fear of flying is common and emphasize that flying is safer than road or rail travel in most developed countries. • Try distraction by talking with other passengers, watching in-flight films, eating or reading. • Tell the cabin crew. Reassurance about strange sounds can help. • A visit to the doctor prior to travel can provide reassurance about general fitness for air travel. • Consider a tranquillizer before departure. It should be stressed that these drugs do not mix well with alcohol. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Recent research has indicated that “cognitive behaviour therapy” can be helpful for more severe cases. The person identifies what they actually fear, and then learns different ways of overcoming it. Courses and counselling on fear of flying: Aviatours provide courses at Heathrow and Manchester airports (Tel: 01252 793 250). Air rage This term has recently been introduced to describe psychological or physical violence occurring within aircraft. It is of particular concern because of the cramped conditions inside an aircraft and the inevitable involvement of not only the cabin crew but also other passengers. There have been instances where aircraft have had to land prematurely to offload disruptive passengers and legal action taken against those involved. What is air rage? There is often a developing cycle of events, which may include delays, exhaustion due to lack of sleep, excessive use of alcohol sometimes to compensate fear of flying, minor irritations due to behaviour of fellow passengers which elsewhere would largely go unnoticed and sometimes anoxia causing irritability in those with pre-existing hypoxic illnesses. Smoking and alcohol: It has recently been recognised that a common cause of air rage is nicotine withdrawal in heavy smokers on long-distance ‘no smoking’ flights. This has now been introduced by many airlines. Alcohol intoxication can also contribute. Prevention Nicotine gum or a mild tranquilliser may be useful ‘prophylaxis’. Passengers should avoid excessive alcohol consumption and discouraging heavy drinking by their travelling companions. Airlines have the right to refuse to carry those who have previously caused disruption on a flight – warnings may be issued (the equivalent of ‘yellow/red’ card system as used at football matches) Altitude Sickness on arrival Healthy people may travel rapidly to 3500 m above sea level but develop symptoms of acute mountain sickness after arrival (headache, nausea, breathing difficulty, mental confusion). Those with respiratory or cardiac problems may experience symptoms on arrival at even lower levels. A few airports are sited above this level, for example, in the Andes and Himalayas, which can mean symptoms, may present after disembarking. An awareness of the symptoms can be helpful and care to avoid dehydration, aggravated by the dry aircraft cabin atmosphere, is important. Dehydration may worsen symptoms. Rest after arrival with only light activity is recommended because strenuous activity will worsen symptoms. Those with serious pre-existing hypoxic respiratory disease can seek advice prior to departure when an estimate of the degree of hypoxia occurring on exercise may be able to predict whether they will have problems. Advice on mountain sickness High altitude holidays are increasingly popular. In South America they include crossing Andean passes often above 4000 metres. Trekkers in the Himalayas, especially in Nepal, often reach similar heights. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania and Mount Kenya are both more than 5000 metres. Only those healthy and trained should attempt such expeditions, and if in doubt medical advice should be taken. All including the physically fit can get acute mountain sickness during rapid ascent if staying for more than 12 hours above 2500 metres. It affects all ages including children when the symptoms may be more difficult to recognise. The altitude difference undergone in 24 hours is the determining factor. From 3000 metres and higher, the risk increases when the altitude difference between encampments exceeds 300 metres. Signs of mountain sickness Early signs of acute mountain sickness include headache, nausea, anorexia and insomnia. If vertigo, vomiting, apathy, staggering and dyspnoea occur, immediate accompanied descent is essential. Failing to descend may be fatal. Prevention Avoid ascents of greater than 300 metres per day if starting from above 3000 metres. If early signs of mountain sickness appear, rest for a day at the same altitude. If they persist or increase, descend at least 500 metres. Acetazolamide can be used as prophylaxis for mountain sickness when a gradual ascent cannot be guaranteed. It should NOT be used as an alternative to a gradual ascent. It acts on acid-base balance and stimulates respiration. It should be combined with a good fluid intake. It should not normally be used in young children except under close medical supervision. Dose: 250mg bd. for adults. A smaller dose (125mg bd) is probably just as effective and gives less side effects. Treatment Initially simple analgesics (e.g. paracetamol) for headaches. Sleeping pills should be avoided if possible. Acute mountain sickness with cerebral oedema. Immediate evacuation or descent at least 1000 metres; oxygen if available. Dexamethasone (12–20 mg daily) or prednisolone (40 mg daily). High altitude pulmonary oedema Immediate evacuation or descent. If symptoms are acute and/or descent is impossible or delayed consider nifedipine (20 mg tds). A useful address For information sheets available to Doctors/Climbers/Trekkers contact the British Mountaineering Council, 177–179 Burton Road, Manchester, M20 2BB. Tel: 0870 0104 878, Fax: 0161 445 4500, web-site address: www.thebmc.co.uk (Ref: The Rose Cottage Surgery. Jane Chiodoni 02/2002) Greater detail for Travel at altitude Definitions High Altitude Between 2400 m and 3658 m. Cochabamba, Bolivia = 2550 m Bogota, Colombia = 2645 m Quito, Ecuador = 2879 m Cuzco, Peru = 3225 m Very High Altitude Between 3658 m and 5500 m. La Paz, Bolivia = 3658 m Lhasa, Tibet, China = 3685 m Base Camps of Everest = 5500 m Extreme Altitude Between 5500 m and 8848 m (the summit of Mount Everest). Most people feel at least a little unwell if they drive, fly or travel by train from sea level to 3500 m. Headache, fatigue, flu-like symptoms, undue breathlessness on exertion, the sensation of the heart beating forcibly, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, minor swelling of the face, feet and hands, dizziness, difficulty sleeping, frequent awakenings and irregular breathing during sleep are all common complaints. These are symptoms of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) which usually develop during the first 36 hours at altitude but not immediately upon arrival. AMS is common and well over 50% of travellers develop it in some form at 3500 m – almost all do so if they ascend rapidly at 5000 m. There is a wide variation in both the rate of onset and severity of symptoms and also at the height at which they occur. The problems are caused by lack of oxygen which leads to hypoxia. Ears and Air Travel Ear problems are the most common medical complaint of air travellers. It is the middle ear which causes discomfort during air travel. Normally you swallow 5 times every minute and air passes up the back of the nose when you swallow and sometimes enters the Eustachian tube which leads into the middle ear space. The air in the middle ear is constantly being absorbed by its lining so air keeps being replaced via the Eustachian tube. In this way, the air is kept at equal pressure either side of the ear drum allowing it to vibrate when sound enters your ear. If the air pressure on each side of the drum is not equal then your ears will feel blocked. What Causes the Air Pressure to Not Be Equal? The back of the nose can be blocked with wet mucus. The lining at the back of the nose is the same as that in the mouth so if you have a common ‘cold’ lots of stuffy wet secretions collect at the back of the nose and block off the entrance to the Eustachian tube. When you swallow, air cannot get to the opening of the tube and so no air is passed into the middle ear. The air already in the middle ear is absorbed and as no more air can get up the tube a vacuum occurs, sucking the drum inwards. This drum can then not vibrate effectively and sounds become muffled, also because the body does not like a vacuum it draws fluid from the lining of the middle ear in an attempt to overcome the vacuum this causes you to have ‘fluid in the ear’ and feel more blocked. The most common cause of blocking this tube is the common ‘cold’ but another frequent problem is hay fever or nasal allergies. Children up to the age of 8 or 9 years have very small undeveloped Eustachian tubes and consequently when they have stuffy noses they find difficulty getting enough air into their middle ear and this is the reason why many children have middle ear fluid and infections. How Air Travel Causes Problems When there is a change in air pressure outside the ear, the entrance to the Eustachian tube has to be clear so that you are able to get air up the tube when you swallow to equalise the air both sides of the ear drum. Every time the air pressure outside the ear changes you must swallow or yawn again to open the tube and let air in at a similar pressure. The greatest air pressure changes are noticed when an aircraft is coming down for landing. The air pressure is lower while the aircraft is in flight and the air pressure is higher nearer the earth. The changes as the plane descends cause a vacuum to form in the middle ear even faster than normal and there is more need to swallow more frequently and let air enter the middle ear. Some pressure changes are unavoidable especially if there is a sudden descent through hitting an air turbulence. You may have experienced similar problems when travelling by train through a tunnel or when diving or when driving in hilly country. What Will Help? Clearing the back of your nose is the main priority so that when you swallow, air can pass more easily into the Eustachian tube. There are nasal sprays on the market which help clear the nose and these are useful for use an hour or so before descent but beware of making the use of these sprays a habit because after a few days use they may cause the nose to become more congested than before. Use them just to clear the nose prior to descent. When your nose is clear of congestion just keep swallowing during descent, this is helped by chewing mints or gum. Yawning is a stronger activator of the tube opening and will help. Do not sleep during descent as you may not swallow enough to keep up with the pressure changes. Another way to unblock your ears is to force air into the Eustachian tube by pinching your nostrils shut and then swallowing until you feel your ears ‘pop’. Do not use force from your stomach or chest to do this, it is sufficient to use pressure created only by your cheek and throat muscles. Ear plugs – These will protect the outer ear from the sudden pressure changes which in turn means that swallowing frequently is not so much required. These may be helpful for smaller children. Pressure on the outer part of the ear at the front will close off the outer ear canal for a short while which may also help in the short term. Reversed Problem – It is important that the outer ear canal is not completely blocked if there is NO problem with your nose or Eustachian tubes. This will cause a negative pressure in the ear canal and a positive pressure in the middle ear, which again could cause pain and discomfort eg if your ear canal is full or wax or the ear plug fits tightly. If Your Ears Will Not Unblock If these exercises and nasal drops do not help and pain persists you will need to seek medical advice. Ref: 4 APPENDIX – Illnesses that can be vaccinated against in the traveller. Hepatitis A Spread by faecal-oral route, either through contaminated water and food, especially shellfish, or through person to person contact when personal hygiene is poor. Travellers from countries with good hygiene are at risk because few are immune from previous (mostly sub-clinical) infection. Typhoid Mainly by food and drink that has been contaminated with excreta of a human case or carrier (faeces or urine). Hepatitis B This is through infected blood and blood products, sexual intercourse with an infected partner and very importantly from an infected mother to her new born child. It is also spread through 'blood to blood' contacts such as through injuries in playgrounds, contaminated instruments during medical, dental, acupuncture, other body piercing procedures, sharing used intravenous needles and face of head shaving when razors are reused. It is highly infectious when viral replication is present (detected by the presence of viral DNA or more crudely by the presence of e-antigen) - this applies to about 10% of carriers. Rabies Rabies can infect many animals but the dog, fox and vampire bat are those most likely to come in contact with humans. Infection usually occurs as the result of a bite by an infected animal; the virus is transmitted in the animals' saliva, usually by inoculation but occasionally by inhalation. Yellow Fever Jungle yellow fever is transmitted among non-human hosts (mainly monkeys) via forest mosquitoes. Spread to an urban area occurs when an infected monkey carries the virus to an area adjacent to the forest and is then bitten by a species of mosquito living in close association with man, usually Aedes aegypti. Both jungle and urban cases occur in Africa (especially west Africa). Urban cases are rare in the Americas. Meningococcal Meningitis Droplet spread via direct contact from nasal carriers or those in the early stage of illness. Nasal carriage is more common in young children than in adults. Japenese B Encephalitis It is transmitted to man by the bite of an infected Culicine mosquito that normally breeds in rice paddies. Pigs and birds such as the Siberian stork act as intermediate or 'amplifying' hosts and they can become viraemic. There is serological evidence that other animals may also be infected but as 'dead-end' hosts - viraemia is rarely observed. Tick-Borne Encephalitis Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is a flavivirus infection spread by the bite of the ixoxides tick (synonyms: spring-summer meningoencephalitis, central European encephalitis, Far eastern encephalitis, Taiga encephalitis, Russian spring-summer encephalitis). It has been recognised since the 1950's that TBE infection can also (rarely) be transmitted via unpasteurised milk from cows, goats and sheep that are infected with TBE. Diptheria Skin infection causing indolent ulcers is common on the limbs of children in the tropics who go around barefoot - this results in 'natural' immunity. Usually later in life respiratory droplet infection is more common and also through contact with articles soiled by infected persons - these are the more serious infections when toxaemia can occur. Tetanus Tetanus spores are present in soil from contamination with human, animal and bird faeces and enter the body through injuries. Neonatal disease may result from contamination of the umbilical cord or after otitis media when a ruptured tympanic membrane allows contamination of the middle ear. Polio There are 3 serotypes of poliovirus (types 1,2 and 3). Infection is usually through the faecal-oral route from contaminated food or drink, although nasopharyngeal droplets may spread it during an acute illness. In developing countries poliomyelitis has caused much crippling disease but now widespread use of vaccine has virtually eradicated disease. BCG (Tuberculosis) Most commonly spread though infected sputum, either from those with pneumonia or asymptomatic carriers. Can also be spread through infected unpasteurised milk. Long air flights, when a passenger has 'open' pulmonary tuberculosis and is coughing close to fellow passengers may also be a risk. Sometimes we recommend our travellers to visit private travel clinics for specialist vaccines or because it may be quicker for you to be seen if travelling at very short notice and we have no available appointments. Below are a list of available travel clinics: MASTA Travel Clinics countrywide (also in Boots the Chemist) For details of your nearest Travel Clinic please call 01276 685040 or www.masta.org Travel Clinics in London The Hospital for Tropical Diseases Travel Clinic Mortimer Market Caper Street off Tottenham Court Road London WC1E 6AU Appointments Tel : 0207 388 9600 Fax : 0207 383 4817 www.thehtd.org The Royal Free Travel Health Centre Pond Street London NW3 2QG Tel: 020 7830 2885 Fax: 020 7830 2741 www.travel-health.co.uk Trailfinders Travel Clinic 194 Kensington High Street London Tel: 0207 938 3999 Nomad Travellers Store Travel Clinic Russell Square Turnpike Lane London London Tel: 0207 833 4114 Tel: 0208 889 7014 Travel Health books - General reading list It is sometimes very useful to read around the subject of travel health before you travel. Such work will prepare you well in advance to help prevent illness and trauma whilst abroad and on your return home. This is particularly recommended for those travelling for long periods e.g. back packing. Understanding Travel and Holiday Health by Dr Gil Lea and Bernadette Carroll. Family Doctor Publications Ltd. in association with the British Medical Association, 1997 ISBN 1-898205-35-3 Price £2.49. Travellers’ Health - How to stay healthy abroad by Dr Richard Dawood (Ed.) Oxford University Press, 3rd Edition 1992. ISBN 0-19-262247-1 Price £9.50 Bugs Bites and Bowels by Dr Jane Wilson Howarth. Cadogan Books, London 2nd Edition 1999. ISBN 1-86011-914-X Price £7.99 Handbook for Women Travellers by Maggie and Gemma Moss. Piatkus Publishers 1995 ISBN 0-7499-1439-4 Price £8.99 Your Child’s Health Abroad - a manual for travelling parents by Dr Jane Wilson-Howarth and Dr Matthew Ellis. Bradt Publications UK. 1998 ISBN 1898323-63-1 Price £8.95 The Royal Geographical Society Expedition Medicine Edited by David Warrell and Sarah Anderson. Publishers - Profile Books (1998) ISBN 1 86197 040 4 £17.99 Stress-Free Flying by Robert Bor, Jeannette Josse and Stephen Palmer. Quay Books, Mark Allen Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1 85642 167 8 (2000) The Travellers’ Good Health Guide by Ted Lankester, Interhealth. Sheldon Press 1999 £6.99 (from supplies@interhealth.org.uk or 157 Waterloo Road, London Se1 8US The Rough Guide to Travel Health by Dr Nick Jones, Rough Guides Ltd. ISBN 1-85828-570-4 Price £4.99 Everything you need to know before you go - Information and advice for independent travel by Mark Ashton. Abroadsheet Publications 3rd Edition 1998. ISBN 0-9525128-2-3 Price £3.50 References Ref. 1. Ref. 2. www.immunisations.nhs.uk (July 2005) www.dh.gov.uk Green Book (2004) Ref. 3. www.sunsmart.org.uk (June 2003) Ref. 4. www.earcarecentre.com (July 2005) Other information in this advice book has been adapted from TRAVAX for health professionals www.travax.scot.nhs.uk . Travax database is maintained and continually updated by the Travel Medicine Team at the Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health (SCIEH). It aims to help Health Care Professionals who are advising travellers about health risks in overseas countries. SCIEH is part of the Common Services Agency of the Scottish National Health Service. Travax is copyright of the Scottish Executive, Department of Health. Important Notice from Travax. Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information supplied herein, but the providers make no warranty, express or implied, as to accuracy, completeness or usefulness of the information and all liability is excluded save in respect of personal injury or death caused by negligence of the suppliers. It is also important to realise that the best decisions on preventive advice or treatment for a particular traveller can only be reached after a careful consultation and risk assessment and with the traveller’s informed consent. The information from TRAVAX is frequently updated and therefore the web site should be accessed periodically to update the information leaflets within these guidelines as necessary. For the public web site of TRAVAX go to: www.fitfortravel.scot.nhs.uk Other sources used in this book are: ACMP guidelines: www.hpa.org.uk www.nathnac.org.uk