CCMAil: December 2004

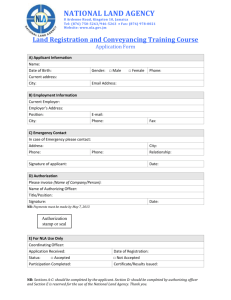

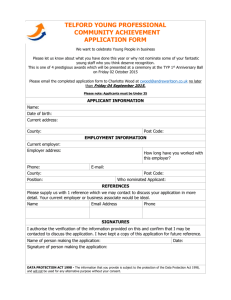

advertisement