20101005 Reflections on Conflict Sensitivity Approaches in CARE

advertisement

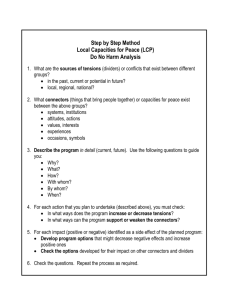

A Reflection on Developing and Implementing Conflict Sensitive Approaches in CARE Burundi April 2010 CARE Burundi’s motivation In 2005 through the CIUK supported Progressing in Peace Initiative (PIP), CARE Burundi began developing a methodology to improve project implementation regarding the social and political conflict context of the country. The CO realized (through field visits and studies) that there was evidence of ‘doing harm’ through certain project activities – in particular those with significant resource allocation. For example, a study conducted in 20051 clearly revealed that food aid projects do impact community power structures and social relations and have both a unifying and divisive effect. The dynamics of food aid to manipulate the social relations for negative results was also clearly indicated through testimonies. Process and achievements In light of these findings, the PIP initiative and the overall post conflict context that Burundi was at the time negotiating, the CO identified Conflict Sensitivity as one of its strategic directions2 in 2006. This strategic direction had the objective of developing conflict sensitive approaches in order to deal with conflict related to the wider context on the one hand, and conflict generated by CARE projects which are implemented in and interact with the wider conflict context. Conflict sensitivity was then defined as a cross-cutting initiative with a goal to build staff and partner capacity in conflict analysis and conflict sensitive approaches to help CARE implement activities with a Do No Harm perspective. The PIP initiative resulted in the development of a participatory methodology to monitor the impact of community development interventions on peace and conflict, as well as to mainstream peace and conflict sensitivity into all projects. This methodology was developed to not only help address issues related to the conflict context overall but to address any problems arising specifically from our initiatives/actions. This methodology was developed to complement the Do No Harm approach. In 2007, CIUK continued to support the CO with the Learning from Peace and Conflict Monitoring (LCPM) initiative, as a follow on to PIP, and more specifically to contribute to the strategic direction of building staff and partner capacity in conflict sensitivity. LPCM aimed to build the capacity of staff and partners (including partner communities and partner agencies) in conflict analysis and conflict sensitive programming. LCPM was to be implemented as a cross-cutting initiative, but focused particularly on two projects SCVM3 and PACTDEV4, as both projects had significant resources attached to their activities and thus perceived as having the most potential to contribute to community level conflicts. At this time the CO employed a Conflict Advisor to manage the LPCM initiative and take responsibility for further developing conflict sensitive approaches for the CO and train project staff and partners through out the mission in Do No Harm and conflict sensitivity. Two rounds of training on The Impact of Food Aid on Community Power Relations and Social Networks: A Case Study of a Hillside in Kirundo Province, Burundi, 2005. 2 “Promote and support reconciliation efforts by conflict-sensitive interventions and an on-going analysis of conflict at different levels (local, national and regional), and to support formal and informal structures in their efforts to strengthen good governance”. 3 SCVM, or the Livelihood Security Project, aimed to improve household economic conditions through the VS&L approach and improving agricultural activities. 4 PACTDEV, the Project of Community Actions for Integrated Development, aimed to lift households out of poverty by supporting the physical rehabilitation of economic and social infrastructure (education, health care, water, food security); strengthen civil society at community level including collaboration with, and capacity building for, decentralized local government structures; address barriers that impede equal access by improving the governance, transparency and administrative efficiency of such services. 1 DNH and Conflict Sensitivity were conducted and as all CARE staff were to benefit from these trainings, it took approximately one year to achieve (all things considered). The rest of time was spent developing tools to use with communities, identifying follow-up strategies and consolidating lessons learnt. The LCPM initiative was funded at £49,865.00 over the span of two years. During the implementation period of LCPM, the Do No Harm manual from the Collaborative for Development Action (CDA) was explored as a resource to help identify and address various challenges, conflict and tensions that were or had the potential to be generated by projects, as well as other relevant resources in the domain of conflict analysis and peacebuilding such as ‘Working on Conflict – skills and strategies for action’ from Responding to Conflict (RTC). The latter resource was exploited much more on the part of conflict analysis that complemented the development of conflict sensitive approaches. The approaches helped significantly in terms of analyzing the conflict context as a whole and how it interacts with project activities; how to deal positively with these interactions between context and interventions; and how to implement projects without contributing to more conflict. CARE Burundi did not use the entire Do No Harm manual; certain themes were chosen as they were most relevant to the context the CO was working in. Some of the themes were explored with our “voisins”5, particularly on identifying peace and conflict indicators and connectors/dividers in order to promote participatory analysis, learning and action. Specific elements taken from the Do No Harm manual entailed: 1. Exploration of Do No Harm as an approach and tool: Here we explored the background of the approach, why and how it was developed and the way its lessons were being integrated thus far in assistance programs, drawing from others experiences. The Conflict Advisor led these reflections and analysis through a series of workshops (each workshop lasting three days) implemented through the LCPM initiative. These workshops were held with key staff in the different regional offices over the course of one year. During these workshops the seven steps of the framework were reviewed and plans made on how best to apply them. 2. A review of the major elements of the framework: This was done in order to see how these elements link with the context analysis so to identify interactions between interventions/activities and the conflict context. At this stage, staff were engaged in ongoing analysis of the impact projects were having on aspects of peace and conflict within the communities where we were working. Specific elements included: understanding the conflict context; analyzing connectors and dividers including factors generating tensions; and analyzing assistance program’s impacts on dividers and connectors. 3. The development of indicators and the identification of connectors and dividers: During this phase, we identified indicators linked to our initiatives and developed some tools that are still being used in the domain of conflict sensitivity. Some examples of connectors / dividers relevant to the Burundi context are: a) the institution of Abashingantahe, a traditional conflict resolution structure that is largely male dominated and embodies traditional values. Although this institution is considered a connector, it can also be considered as a divider when one takes into account the current governance system; until now during the process of decentralization, these traditional structures are not officially recognized. b) The political parties have also always played both roles of either dividing and / or connecting people; an example of extreme division would be those who incite hatred and violence during this 2010 pre-electoral period. 5 Respectful term used by CARE Burundi for referring to beneficiaries – voisins means neighbors. 2 Thus, certain aspects of Do No Harm were integrated in order to help the CO implement projects more effectively, and to assume more responsibility for our actions by holding ourselves accountable for the effects that our initiatives have in aggravating or prolonging conflict, or in reducing and addressing conflict. For example, one important aspect of Do No Harm that CARE Burundi considers essential is the regular examination and analysis of the context. This helps the CO in terms of understanding how the context is evolving and how this affects our interventions, either positively or negatively. The SCVM project experience had shown that there were considerable conflicts and challenges generated or made worse by the project’s actions, and conflict sensitivity was introduced in order to ensure activities were not contributing to negative impacts (including destructive conflict) in the beneficiary communities, in particular between different social groups. For example, there were some people whole stole or ‘deviated’ resources that had been distributed; some cases of corruption are still being dealt with in the local courts. Some tensions have also been observed between members of Solidarity Groups when money is borrow and not paid back, as well as conflicts driven by Solidarity Group leaders who use their power over others to use the money. CARE Burundi has learned that any initiatives which aim to bring positive change in communities should march together with mechanisms to help people deal with issues and conflicts provoked by those changes. Change affects people in different ways and can often create or contribute to other conflicts. The example we can provide here is the case of women that are now resolving land conflicts and domestic violence in their communities. Early on, the response to the role of women as mediators was not accepted and some people felt that culture was being offended and so they opposed women’s involvement; this is still happening in many cases. Existing Peace Clubs actively help people resolve conflicts without asking for anything in return, while there is the traditional conflict resolution body the Bashingantahe and local leaders who still feel ashamed and vehemently oppose women’s participation. The Abatangamuco (male and female change agents) are still misunderstood and opposed by some community members who think that the involvement of men (and husbands and wives together!) is breaking down culture - and it is! What is important to note here is that these change agents, although having increasing positive impact on their communities and families, are also challenging deep rooted traditions and beliefs and as such are shaking things up – contributing to tension and conflict. These transformative processes need to be monitored and supported, as well as protected from any risks associated with challenging the status quo. The DNH approach has helped improve staff sensitivity to negative impacts and destructive conflict that might be generated by our projects. In the past there were frustrations in the communities of people who were not happy with CARE saying that resources were not being administrated in a good (fair) way. After the trainings a new methodology was introduced in order to reduce those frustrations; this is about including community members and leaders in the process of implementing activities. In addition, staff started organising sessions with community members in order to analyse together what was going wrong with interventions,; conflicts around CARE activities, how project activities were impacting on peace and conflict, how projects’ initiatives are affecting community relationship and options to undertake so to improve our initiatives. Staff also requested a simplified tool/guide outlining basic concepts on conflict sensitive approaches and analysis to help themselves in the field; the tool was developed by staff of PACTDEV and some local partners assisted by the Conflict Advisor. We hope the tool can also be shared with other COs since it is being applied at the grassroots level. It was simplified to include aspects of conflict analysis in a way that involve more considerably community members in the learning process. This tool has been elaborated in the local language Kirundi and has been distributed to leaders of Peace Clubs and other Community-based Organizations to help facilitate their mission. 3 The lessons learnt 6 As we are intervening in a complex context and as conflict is dynamic, realities of the context in which we operate can change from time to time because of any new social or political factors which appear and have influence on it. Project / program staff must be skilled in DNH and conflict sensitivity so that they are be able to conduct critical analysis of the context in which activities are implemented. The importance of developing strategies together with community members to ensure there is no corruption during the process of targeting beneficiaries and initiating inclusive community structures that can follow-up activities. As we are operating as facilitators of social change, DNH has proved that any initiative brought into community has always both positive and negative impacts and that there is always interaction (positive and negative) between the context and project activities. For instance, there is always some level of conflict/tension between people who benefit from trainings and sessions organised by CARE and those who have not. Even providing a small amount of transportation money causes problems between those who are invited to attend trainings and those who are not, but who still work with CARE projects - CBOs6 for example. Some leaders of these CBOs have even been marginalized by their neighbours who say: ‘you are no longer ours, you are CARE’s people; everything you are doing is for getting money from CARE’. Other say: ‘Do not bother yourselves, CARE is always there to assist you, etc’. There are also instances when materials such as T-shirt, umbrellas and bicycles are given to CBO leaders to facilitate activity implementation, and other CBO members accuse the project of promoting injustice and favouring some to the detriment of the rest. There have even been some cases of members who have decided to abandon their CBOs because of these misunderstandings. When we skill community’ members in Do No Harm approaches, they become sensitive to other issues in their neighborhoods. For instance, some Peace Club members have told CARE that if we really want to help build sustainable peace, we should reinforce their capacities much more in Good Governance, Human Rights and Advocacy so that they themselves can effectively influence local leadership and governance structures and improve social justice. By exploring DNH and other conflict sensitive approaches, we have discovered that we need to also explore more broadly the interactions between the broader socio political context and the activities being implemented. The context should be explored at the both national and local level since conflict exists at the national level that influences life and relationships at the community level. In this sense, even the activities we are implementing can as well be influenced by the wider context. For instance, when the political context is fragile, those who suffer the most can be found in the communities where we work. For example, during this 2010 electoral period some local politicians are intent on mobilizing people and try to capitalize on meetings of CBOs, including CBOs who consider themselves politically neutral (such as the Peace Clubs). If the governmental institutions are not stable the ones that suffer more from the consequences are the grassroots populations. Briefly, stability and instability at a national (even regional) level affect people from the bottom up to the top. Conducting regular contextual analysis helps us to positively address situations where, for example, some political leaders want to take advantage of CARE activities being implemented in order to achieve their interests. CBOs refer to the Peace Clubs, Solidarity Groups and other community structures working with CARE projects at the grass roots level. 4 The key to success in our context is in valuing first the voisins role in implementation. The more people feel valued, the more they feel ownership of the program and the more likely it is activities will be realized and without harm or conflict. Presently, most of the CBOs / Peace Club members are becoming sensitive to the challenges and issues raised by our interventions and have the capacity to help project staff deal positively with these issues when they arise. Some CBOs have even initiated a new system of dealing with conflict whenever it occurs in their groups. Since they are aware that there might be misunderstandings and problems provoked by our projects, these CBOs have established a small cadre that help to analyze together situations before they involve (if they need to) project staff. For example, CARE aims to equip leaders of Peace Clubs and Solidarity Groups with the skills and methods to resolve arising conflicts within their groups. This ensures ownership of the conflict sensitivity approaches and if necessary CARE staff and partners can assist. If we want to maximise the impact of our programs on promoting and sustaining peace and limiting conflict in the communities we work, CARE must develop strategies to inspire people to keep monitoring peace and conflict indicators, dividers and connectors which constitute opportunities of consolidating their own initiatives of mutual trust amongst the population. Here we refer to what is likely connecting them in their area such as culture, nationality, language, their CBOs, schools, development actions, etc., as connectors and dividers at the same time such as political parties, politics, religions, beliefs, etc. For instance we have peace clubs that decided to build schools and roads in their areas which are certainly connectors. By engaging in this work themselves, they feel connected to and responsible for their own development. Do No Harm has to be explored and implemented together with other concepts such as peacebuilding and conflict transformation so that it becomes effective and practical during program implementation. Conflict Sensitivity and Do No Harm help us to implement activities without exacerbating conflict; by trying to maximise positive impacts. While other transformative approaches of conflict analysis and prevention and peacebuilding and can help us analyse the wider conflict context and how this interacts with our development activities; interactions that may negatively affect our initiatives and stop us from reaching our objectives. Conclusions As CARE Burundi continues to operate in a post-conflict context, it is difficult (if not impossible) for our work to ever be 100% neutral. Although it is clear that development activities are neither the sole cause of nor end to conflict, none the less interventions can be a significant influencing factor in contributing to or reducing conflict. Relief to development interventions will always influence inter-group relations, and can either contribute to or alleviate inter-group conflict. Thus skills in conflict sensitivity, including analysis and developing strategies to manage conflict, are essential for any CO operating in conflict, post conflict and even stable contexts. In this 2010 electoral period, CARE Burundi is particularly sensitive to the context and potential for conflict and is thus promoting and building capacity in other complementing approaches such as conflict transformation, peacebuilding and popularizing conflict sensitive methodologies throughout our programs. Next steps Unfortunately not all project staff and partners have had the opportunity to be trained on these different subjects, as we have new staff and new partners for new projects; this is 5 currently underway with Ntunkumire7 project and will continue into FY11 with other projects / programs. The CO will benefit from refresher training, including exploring new approaches that complement the ones already used such as Reflective on Peace Practices8. CIUK is currently supporting a ‘real time’ evaluation of Peace Clubs in Burundi and the impact of their work on peacebuilding – at community and national level. Stay tuned for the final report and video documentary for sharing and learning! For more information contact CARE Burundi’s Conflict Advisor Chartier Niyungeko Chartier.Niyungeko@co.care.org 7 8 Ntunkumire means Don’t Exclude Me: This project aims to promote good governance and space for expression of the voiceless. RPP: Reflecting on Peace Practices, a CDA resource which complements the Do No Harm manual. 6