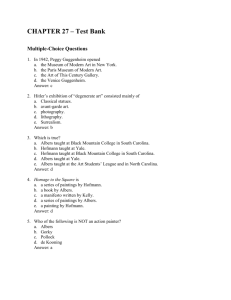

A Biography of Moura Boudberg

advertisement

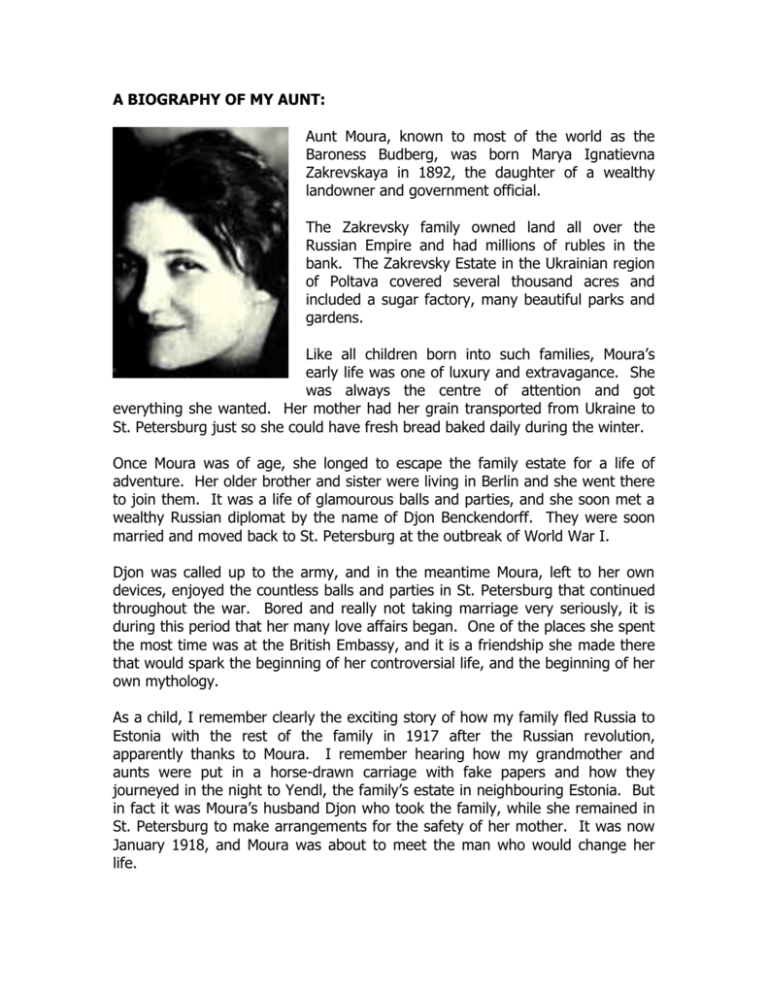

A BIOGRAPHY OF MY AUNT: Aunt Moura, known to most of the world as the Baroness Budberg, was born Marya Ignatievna Zakrevskaya in 1892, the daughter of a wealthy landowner and government official. The Zakrevsky family owned land all over the Russian Empire and had millions of rubles in the bank. The Zakrevsky Estate in the Ukrainian region of Poltava covered several thousand acres and included a sugar factory, many beautiful parks and gardens. Like all children born into such families, Moura’s early life was one of luxury and extravagance. She was always the centre of attention and got everything she wanted. Her mother had her grain transported from Ukraine to St. Petersburg just so she could have fresh bread baked daily during the winter. Once Moura was of age, she longed to escape the family estate for a life of adventure. Her older brother and sister were living in Berlin and she went there to join them. It was a life of glamourous balls and parties, and she soon met a wealthy Russian diplomat by the name of Djon Benckendorff. They were soon married and moved back to St. Petersburg at the outbreak of World War I. Djon was called up to the army, and in the meantime Moura, left to her own devices, enjoyed the countless balls and parties in St. Petersburg that continued throughout the war. Bored and really not taking marriage very seriously, it is during this period that her many love affairs began. One of the places she spent the most time was at the British Embassy, and it is a friendship she made there that would spark the beginning of her controversial life, and the beginning of her own mythology. As a child, I remember clearly the exciting story of how my family fled Russia to Estonia with the rest of the family in 1917 after the Russian revolution, apparently thanks to Moura. I remember hearing how my grandmother and aunts were put in a horse-drawn carriage with fake papers and how they journeyed in the night to Yendl, the family’s estate in neighbouring Estonia. But in fact it was Moura’s husband Djon who took the family, while she remained in St. Petersburg to make arrangements for the safety of her mother. It was now January 1918, and Moura was about to meet the man who would change her life. Robert Bruce Lockhart had been the Consul General at the British Embassy. After the revolution, the British Prime Minister charged him with a mission of the utmost importance. Lockhart was to befriend the new Bolshevik government and convince them to carry on the war against the Germans. Lockhart, who had leftist sympathies, had initially encouraged the British government to do business with the Bolsheviks and had become close to Trotsky. But he soon changed his mind, and began arguing for an Allied intervention to overthrow the Bolshevik government. A colleague at the British Embassy introduced him to Moura in March 1918 and before long a passionate love affair began. Under the pretext of looking after her mother, Moura decided to stay in Russia to continue her affair and she moved into Lockhart’s flat in Moscow, to be near the new Bolshevik government. Months passed and Moura discovered she was pregnant by Lockhart. They made a pact, that they would divorce their respective spouse, and leave their families to be together. But in August 1918, the most important event in their lives took place. A Socialist Revolutionary named Dora Kaplan carried out an attempt on Lenin’s as he was leaving a rally at a factory. He was hit by two bullets and appeared to be fatally wounded. The Bolshevik government immediately launched an investigation. They believed the attack was the result of a conspiracy, and the Secret Police, the CHEKA, began their search for suspects about rounding up suspects. For a while now they had been suspicious of Lockhart and his mission in Moscow. So they went to his flat and broke down the door. Inside they found Lockhart and his entourage and they were immediately placed under arrest. One of those arrested was my aunt Moura. Now the mystery begins: Lockhart is released within days of his arrest. Out of captivity, one of his first acts is to ask after his beloved Moura. He discovers that she is in fact still in custody. Concerned, he goes to see her in prison. Upon arrival, however, Lockhart is re-arrested. This time, he is accused of being behind an imperialist plot to overthrow the Bolshevik government and impose a military dictatorship under Allied control. The charges are serious and there is talk of the death penalty. Soon after, Moura is released. What had happened in the interim for Lockhart to be re-arrested? Why was Moura released so soon, and apparently without charge? Did she do a deal with the Soviets? Many believe that Moura was given her freedom on condition that she become an informant for the Soviet Secret services – in effect, a spy. She then, the theory goes, gave them information to make Lockhart sound guilty. My family, of course, have continuously denied this. Only the archives of the KGB could shed light on the truth, and I intend to gain access to them, to put an end to 80 years of speculation as to whether or not Moura was a spy. Thankfully, Lenin recovered from the assassination attempt and within a month a deal had been done for Lockhart’s release. He was returned to Britain in exchange for the Bolshevik representative in London. Moura was said to be have been devastated by Lockhart’s departure. Judging from the letters she wrote, she desperately loved him. She was terrified he would leave her. She had lost his baby to a miscarriage but still clung to their pact that they would meet in Stockholm at the earliest opportunity and run away together. Lockhart received her letters, but soon he stopped replying. Now the next mystery began. Moura, hopelessly in love, lived for this meeting in Stockholm. She did not want to return to Estonia for she hoped that the meeting would happen soon. She hung on for two whole years in Moscow waiting for word from Lockhart but word never came. Only in 1921 did Lockhart send her a letter in which he, in very cold terms, informed her that he had another child by his wife and that the affair was over. As a child I believed Moura had stayed in Moscow for love and for her mother, but there are other, darker rumours that still abound: that she stayed to repay her debt for being freed during the Lockhart affair, and worked as a KGB informant, giving information on her next lover, the great novelist and Socialist visionary, Maxim Gorky. Zinoviev, the Bolshevik revolutionary who hated Gorky, was said to be behind this plot. Again, only the KGB archives could she light on this mystery. One thing is for sure, she did not idly wait for her beloved Lockhart to write to her, she busied herself with her next conquest. Whether she spied for the Soviets or not, there is no doubt that after Lockhart left Moscow, Moura returned to St. Petersburg and looked after her mother in the last months of her life. Moura was still only 27 years old and she began to reinvent herself, all of her friends having fled the country or been killed. The fact that she was an aristocrat meant it was amazing she managed to survive. She had, however, come to see the revolution as being inevitable and had developed a leftist, communist mode of thinking: perhaps by conviction, or perhaps because it helped her to survive. Moura the aristocrat was now penniless, so she tried to get money any way she could: she pawned her dresses and borrowed money from whoever would lend it. One of her few friends from the old Russia was the former interpreter at the British Ebmassy, Korney Chukovsky. He was working on a publishing venture with Maxim Gorky. They were publishing the English classics and Moura, having learnt English as a child, was employed as a translator. Gorky was instantly captivated by her and thus began an affair that would span nearly 20 years. It wasn’t long Moura moved into Gorky’s flat on Kronverskaya Prospekt. I have always believed that she fell in love with him too, but there are those who believe that she seduced him on KGB orders, and that she informed on him through out their relationship. Gorky’s flat was a bohemian abode full of artists, writers and painters. Moura hung out with the great novelists and poets of the day, like Alexander Blok and Evgeny Zamyatin. She also met countless foreign writers of world renown. The most notable of those arrived with his son Gip in 1920. That man was H.G. Wells. Gorky asked Moura, the only English speaker in the flat, to interpret for him and Moura accompanied Wells everywhere. Wells immediately fell in love with her, writing in his memoirs of how she snuck out of her room one night into his embraces, and their love affair began then and there. But conspiracy theorists say that Moura was charged, again by Zinoviev, to shadow Wells’ visit, even accompanying him on his visit to Moscow to meet Lenin. Again, this part of the story is still shrouded in mystery. By the end of 1920, Gorky was gravely ill. His health was so bad that he agreed with Lenin that he should leave Russia to get better healthcare abroad. Moura knew that it could be dangerous for her to remain in Russia after Gorky left. He was her protector by now and things could turn bad for her without him there. Not having an exit visa, she decided to leave in secret. At that time, people smugglers would sneak people across the frozen Navora River over to Finland for a fee, and Moura paid for them to take her. From Finland Moura intended to go to her family in Estonia. They left in the middle of the night, but were caught by Soviet border guards. She spent several weeks in prison, but somehow avoided being executed, which is what happened to most aristocrats who were caught trying to escape the Soviet Union. She always told the story of how it was Gorky who intervened on her behalf, and who convinced the head of the CHEKA, Felix Dzerzhinsky, to let her go. But is this the true story? Did Gorky hold this kind of sway? Or was another kind of deal done, not by Gorky but by Moura? Could she have been recruited? Whatever the truth, Moura was not only released but given an exit visa to leave Russia (again, she would claim this was thanks to Gorky). So in the Spring of 1930 she left for Estonia where she would see her children for the first time in 3 years. While Moura had been in Leningrad, her husband had been shot dead in the woods near the little summer house where the family now lived, since their land had been confiscated by the new Estonian government. She was now a widow, and a widow without a passport. She soon re-married, to a gambler and penniless aristocrat called Baron Nikolai Budberg. She would acquire his name and, more importantly, a passport. For this, she repaid much of his debts – with Gorky’s money. It was this return from Russia where suspicion began that she was working for the Soviets. The Baltic aristocracy did not accept the legitimacy of the Bolshevik government and they condemned anyone who, like Moura, had dealings with them. She was not even allowed to see her children until she had explained herself and she was put in front of a so-called ‘Court of Honour’ in which members of the Baltic nobility would judge if she had committed a breach of ethics, or, a breach of the law. She lied about much of her time in Russia, telling them that she had been there to nurse her sick mother and mentioning nothing about Lockhart or Gorky. It is only when Lockhart published his memoirs that much of the family discovered the shocking truth about their love affair. After her marriage, Moura contacted Gorky and his entourage once again. They were based in Germany now, and as German was Moura’s second language and Budberg was also fluent, they decided to move to Berlin. Before long, Baron Budberg and Moura separated and she stayed on in Germany, working as Gorky’s secretary at his new home in Heringsdorf on the Baltic coast. They became lovers once more, and lived in separate quarters from the rest of the household. In 1924, with Gorky’s health going from bad to worse, he was invited by the Italian government to come and live in Italy. Gorky was delighted and brought Moura with him, setting himself up in a villa called Il Sorrito, near Sorrento. The villa soon became open house for Russian and Western intellectuals. People came, talked to the great man, worked and stayed for days, weeks, and sometimes months. My grandmother spent two months there with Moura. Gorky had by this time fallen out somewhat by the Soviet authorities. The question is: was Moura using her time there to inform on him and his meetings to the Soviet authorities? She would certainly have been the perfect person to do so. One of the visitors to the villa was H.G. Wells, who came partly to see Gorky but partly also to see Moura. They saw each other occasionally also on her brief visits to England, where through Gorky she had also become well known to the literary community. In 1927, Gorky began visiting the Soviet Union for the first time in years. Stalin was asking for the USSR’s great literary hero to come home and his wife Ekaterina Pavlovna, now living in Moscow, was also hopeful for his return. He was also, in actual fact, running out of money in Italy and Moura knew that his departure was inevitable. So she started making plans for a life without Gorky, and for this she looked to H.G. Wells. Moura soon moved back to Berlin where she acted as Gorky’s literary agent in the Europe. She was still only thirty five and began to spend more and more time in England, courting the literary community on Gorky’s behalf. As National Socialism gradually took hold in Germany, England seemed the obvious place to move, where she would also be able to continue her sporadic love affair with H.G. Wells. In 1931, she moved over for good, bringing my grandmother with her, who had been living with her in Berlin. From that year on, H.G. Wells began to take over more and more of her life. He was fascinated by Russia, and by 1932 was pressuring Moura to marry him. But she was still carrying on her affair with Gorky, and was playing both men off against each other. She carried on this double game for years. For instance when she heard that Gorky was moving back to Russia for good in 1933, she was on holiday with Wells at the time. She made up an excuse like a family bereavement and travelled to Istanbul to meet Gorky one more time before he got on a boat to the USSR. It was the many lies that Moura told which first aroused H.G. Wells’ suspicion that she was a spy. She lied to him about her affair with Gorky, saying they were simply friends and that she was his secretary. She also lied to her about her many trips to Russia after Gorky’s return there. She told him she could never go back to Russia for fear of being sent to a prison camp. In reality, she went at least once a year until Gorky’s death in 1936. Humiliatingly, Wells found out about these lies when he went to Moscow in 1934. There he met many friends of Gorky who told him how she had visited them at home only a few weeks before. Wells confronted Moura on a trip to Estonia in 1934 shortly afterwards. She denied his accusations vociferously despite the fact that so many people had attested to having had dinner with her in Moscow. Such was her force of personality that Wells believed her, or pretended to believe her, but it seemed that aside from anger and humiliation he was wondering what else she had been doing during all those trips. Was Gorky really still powerful enough to get her a visa to Russia, or did she have other backers? Was she passing information to Russia about Wells and other British figures to the Soviets? Wells was suspicious. He wrote to his friend Lady Aberconway: ‘Faint aroma of espionage in Moura’s world in Berlin, Paris and Knightsbridge. I’m bored by a Moura who… rambles round corners and for all I know is a spy. I’m not going to be trailed.’ In the book by his illegitimate son Anthony West, Wells apparently confronted Moura about her spying and she confessed to him ‘her full involvement with the Russian secret services’. Is this true? If so, the great writer omitted it from his autobiography. It may be that he wanted to protect her, for despite Moura’s lies and fabrications, Wells remained devoted to her, and she to him, until his death. Moura’s trips to Russia came to an end after Gorky died in 1936. Moura was by his bedside when he passed away and is said to have stood next to Stalin at his funeral. This has led to sinister conspiracy theories: Russian writers and historians have claimed that Moura had been entrusted with Gorky’s sensitive archive of correspondence before his return to Russia in the early 30s. According to them, shortly before Gorky’s death Moura received a visit from KGB agents at her home in London. They told her that Stalin himself wanted to see the archive, and that she must come to Russia at once. If she did not deliver the archive to Stalin, the agents told her she would never see Gorky again. Moura, knowing that Gorky was gravely ill and might not live much longer, is said to have agreed. She allegedly handed the archive to Stalin, providing him with mountains of evidence against his enemies which he would use to send people to their deaths during the Great Terror of 1937. Her reward was to see Gorky before he died. Some of the allegations are worse still. There are those that believe that Stalin, disliking Gorky’s idealism, ordered his death. He is said to have been poisoned, the dose having been administered by Moura Budberg. Again, we must examine the evidence and meet the Russian writers and historians who hold this view. With Gorky dead, Moura settled fully in England. She became the friend of the great and the good, and her nightly vodka and cheese parties were attended by anyone who was anyone. She courted left wing thinkers, actors, and even met the likes of Anthony Eden, Winston Churchill and, during the War, Charles de Gaulle. Her visits to Russia stopped, but the rumours about her spying continued, and MI5 continued to observe her for 25 years, but never to any avail. During the war, Moura worked for a French journal called La France Libre and thanks to her many of the greatest thinkers in Europe contributed to it. But in France, it was thought that she used to job to glean secrets vital to French national security, and the secret service there also opened a file on her. Wells’ death in 1943 marked the end of an era for Moura, but she continued her life as British society’s Russian Grande Dame. She began working in the movie business, first as assistant to the film director Alexander Korda. She went on to be an advisor on all things Russian, giving tips to the likes of Michael Redgrave and Lawrence Olivier on how to play Chekhov. She even played a small part in Carol Reed’s film The Accident, and her romance with Robert Bruce Lockhart became the subject of a film by Michael Curtiz called British Agent. This made the myth of Moura’s life even more colourful and she encouraged this. It was difficult for anyone to know what Moura was really like, but everyone agreed that she lied about everything. Her ‘easy way with fact’, as H.G. Wells put it, means that it was always difficult to separate truth from fiction. This would certainly be the perfect qualifications for a spy. She even encouraged the espionage stories about her because they made her sound more interesting. To me, the accusations of spying have always been the most exciting thing about the Moura legend. But over the years I have been overwhelmed by the desire to unpick that legend. Moura was determined go down in history, and to make sure that her history was one that would keep people guessing. Agent Moura will be a historical detective story, a journey through time and space aiming the many dots of incredible life together; to put to sleep age old legends, and to find out if I really do have a spy in the family.