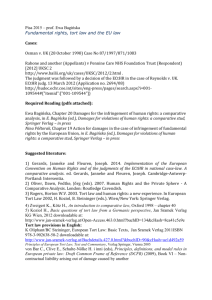

Tort Litigation Between Spouses - Harvard Negotiation Law Review

advertisement