44. The Plight of the Industrial Worker

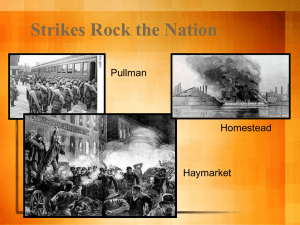

advertisement

The Plight of the Industrial Worker The story of the labor movement is intertwined with the story of immigration in the history of the United States. Immigration picked up just as a demand for labor increased in growing industries. These two dynamics sound as if they should have marched together, fife and drum, alongside the flag-bearing American Dream, but labor strife led to deep dissatisfaction as the 19th century unfolded. Immigrants swelled American cities. 87% of the urban work force of Chicago consisted of immigrants. Detroit and Milwaukee workers were 84% immigrant. Cleveland and New York City came in at 80%. Difficulty in forging a united labor movement resulted from the ethnic, language, and religious barriers created by the variety of homelands from whence urban industrial workers came. This diversity resulting in disunity is only one of the hurdles organized labor had to leap in order to become an accepted institution in American life. The first attempt at widespread organization of labor immediately reveals key themes. Ira Stewart, a Boston machinist, organized the National Labor Union which should make an easy name to remember for the first attempt at a national labor union. Stewart and his compatriots wanted an 8-hour work day. Their willingness to push for this concession was answered by the federal government which instituted an 8-hour day for federal employees in 1868. Watch for this leadership to continue as the labor movement gets rolling, but also keep in mind that if federal employees had reduced hours, more workers would have to be hired to accomplish the same productivity, so opportunities for graft provided an incentive. Don’t forget that the labor movement originated during the Gilded Age. Another key dynamic is revealed in that the National Labor Union enjoyed a membership of 640,000 by 1868, but the Panic of 1873 killed this first attempt. Observe that in times of depression labor unions generally suffer because strikes look silly when a long line of men who have lost their jobs are waiting outside your factory and are willing to work for lower wages than are you. Membership in unions has always been curtailed by economic decline. A look at the severity of the Panic of 1873 is in order. The depression lasted until 1879, and business declined one third with the collapse of Civil War financier Jay Cooke’s fortune. Thousands of American workers lost their jobs. One third of the workers of New York City were unemployed during the winter of 1874-75. Uriah Stephens had begun a more successful national labor union back in 1869. His Knights of Labor organization survived the Panic of 1873, and by 1880 membership of both skilled and unskilled workers soared. The most influential KOL leader was Terence V. Powderly who, ironically, disliked discussions of wages, hours, conditions, job security, and pensions and was reluctant to call strikes. These traditional labor union concerns were less important to Powderly than was the simple fraternity of being organized. He wanted KOL solidarity to improve industrial output within each industry that joined. Three other labor organizations should be observed as they formed during these turbulent times. As the full force of the Panic of 1873 was felt, the Socialist Labor Union was founded in 1874. This radical organization was bent on the overthrow of the US capitalistic system by a revolution and gave rise to a political party which is still around today. Another party clamored for the coinage of silver and the printing of more paper currency to increase inflation to help mainly farmers in ways we will analyze later. The Greenback Labor Party was thus a forerunner of the Populist Party, the most successful third party in US history. The third group of note was a labor organization, also radical, that was associated strictly with Irish coal miners. Irish immigrants transplanted a secret society called the Ancient Order of Hibernians to US coal mines where they were referred to as the Molly Maguires (after a female labor organizer). The Molly Maguires targeted bosses they perceived as unfair and dropped cryptic “coffin notices” in their mail. Some of these bosses started turning up dead. This is a main reason why I don’t have a suggestion box in my classroom any more because when I did we got to the Molly Maguires and “coffin notices” started appearing in my suggestion box—HA! HA! I even got a bullet one day. But, back to Irish terrorists in coal mines. The famous Pinkerton Detective Agency, created by a Civil War intelligence officer named Pinkerton, was called on by the mine owners to infiltrate the Molly Maguires. The Pinkertons did so successfully, and 20 Molly Maguires were hanged. These events are part of the reason labor had such a terrible reputation in American history. The Pinkertons would be called on again. Federal troops would even be called out to put down labor violence by more than one Gilded Age president. Rutherford B. Hayes sent federal troops to intervene in the National Railroad Strike in 1877 (he probably got a phone call about it). Striking railway workers paralyzed railroad traffic. Militia troops were called in to suppress a growing mob and killed 26 when the mob turned on them before escaping with their lives. The mob then destroyed around $5 million dollars worth of railroad property, all because the railroad had cut their wages by 10%. You might be called on to compare and contrast labor strikes with the protests of farmers, so be aware that labor unions always seemed to invite a more sinister reputation. Despite the negative image produced by labor agitation and despite the growth of the American economy, industrial workers had a serious problem. Just like every other economic indicator, their wages rose exponentially 37% from 1890 to 1914. Why would they have a problem then? Because the cost of living during the same time period went up 39%! These workers, they reasoned, helped create the new wealth of the nation, but they sensed (or their labor leaders told them) some rather startling statistics. During the Gilded Age the top 10% of wealthy Americans controlled 34% of the nation’s wealth. The bottom 10% controlled only 3.4% of the wealth. This comparison is easily explained and in some way fitting, but very difficult to present to the bottom 10% (or to anyone in the lower 50%) as just. Labor leaders thus organized strikes, especially when management cut wages. 477 major strikes occurred in 1881 in the US. In 1891 this number jumped to 2,000 and was still at 1,800 in 1900. Now, let’s examine the demise of the Knights of Labor as a telling episode in the labor movement. Remember, Uriah Stephens had founded the KOL in 1869 and remained its president until 1871, but the most influential president was Terence Powderly who ran the KOL through the height of its power from 1879-1890. Powderly tried to keep the KOL a social and fraternal organization like the Grange for farmers, but his organization got more and more involved in strikes and demonstrations. The worst of these was on May 4, 1886 when the KOL led a demonstration at which eight anarchists threw bombs at the police. Seven policemen and four workers were killed. This episode occurred at the Haymarket Square in Chicago and therefore went down in history as the Haymarket Square Riot. The eight anarchists were convicted, and it was proven that they were not a part of the Knights of Labor, but the reputation of the KOL was irrevocably damaged leading to its eventual collapse. Samuel Gompers, an immigrant Jewish cigar maker, rose up as he saw the Knights of Labor slipping and initiated the next step in the progress of the labor movement. Right after the Haymarket Square Riot, Gompers formed the American Federation of Labor, or the AFL. This national labor union had 140,000 members by the end of 1886 and 2 million by 1914. A key strategy was to limit membership in the AFL to skilled laborers. Gompers said skilled and unskilled laborers had nothing in common. The skilled laborers pushed for a shorter day, better wages, safer working conditions, and the removal of children from the workplace. This last point was not out of tender care for youngsters but a reaction to the fact that child workers drove the wages of adults down. Gompers and the AFL were perfectly comfortable striking and laid a permanent foundation for labor unions in the US. The AFL is still active today, although it joined with another organization to become the AFL-CIO. The efforts of all labor unions were hampered by “yellow-dog” contracts where employers exacted promises not to join a union from workers as they were hired, especially in hard times. Owners and managers of factories wanted “open shop” facilities where any workers could be employed. Labor organizers fought to create “closed shop” factories where only union workers could be employed. All the while, factories remained dangerous places to work. By 1913, 25,000 workers were killed in factories and 750,000 seriously injured! The plight of industrial workers remained associated with poor immigrants in America’s growing cities. 1/3 to 1/2 of Gilded Age workers lived in poverty, conditions that remained severe until 1900. Urban improvements began by 1910 to offer a new American Dream, but for city-dwellers it was long in coming. Immigrant workers were pressured to “Americanize” as quickly as possible. Social progress and assimilation meant, at bottom, that immigrant children were alienated from their foreign-born parents through the indoctrination powers of public schools. Children learned English faster than did their parents, and third-generation Americans often did not learn their grandparents’ native tongue at all. Boss politics exploited immigrant workers and the pragmatism and materialism of America made immigrants hungry for consumer goods. The Sears and Roebuck Catalog, first published in 1897, might be the only common experience of immigrant workers. The mail-order company was able to undersell shops and drove prices for consumer goods down, increasing mass production. This growth contributed to an uneven distribution of wealth and prosperity that exacerbated the class and ethnic (and generational) isolation immigrants felt. When national markets were achieved in the US, a new and incredibly wide variety of goods became available, but being a nation was on shaky ground again. Meanwhile, laborers fought to secure decent jobs and for the right to keep them decent using collective bargaining, the fundamental principle behind labor unions. The progress for the labor movement prior to the turn of the century, however, was almost completely undone by the aftermath of two devastating clashes between labor and management (and the government) in the 1890s. These two strikes touched off the worst labor violence in US history and set back the progress for decades. In 1892, Andrew Carnegie had left the country for Scotland and left his Homestead Steel Plant in Pennsylvania in the hands of a manager named Henry Clay Frick. Frick did not inherit the interest in compromise of his namesake. While his boss was away selecting a castle or some such vacation episode, Frick decided to try to break the labor union that had crept into US Steel. He hired a private police force of 300 Pinkerton detectives and then cut the workers wages. When the union struck and took over the plant, Frick sent the Pinkertons in by barge on the river next to the plant. Before the barges even landed shots were fired from the shore. When the Pinkertons did disembark, workers snuck in behind them and burned their barges. The Pinkertons fought for their lives while 7,000 state militia troops were called in to take back the plant. An anarchist tried to assassinate Frick in his office, shooting at him and stabbing him from across Frick’s desk, but failed. When this plot failed, the Homestead Steel Plant of US Steel became an open shop. Carnegie sent a terse congratulatory telegram across the Atlantic which read, “Job well done STOP Life worth living again STOP” The second violent strike in US history was perpetrated by workers for the Pullman Palace Car company. All of Pullman’s workers lived in a town which he had built, and when he cut their wages they felt trapped because he did not lower rents nor prices at his company stores. Rising socialist Eugene V. Debs organized a national strike in 1894 where railroad workers across America refused to hook up Pullman Cars. Grover Cleveland used an injunction, an executive order or a court order, to order workers to hook the cars up and move the nation again. To convince Debs and the socialists to comply, the president sent in federal troops in an assertion of property rights. Remember, every strike robs from the owner of the property whether it is a factory, railroad, or baseball team. The vehemence of the labor movement that spawned the Pullman Strike, as it was called, stemmed from the severity of the Panic of 1893. Again, this depression was the worst the country had ever seen. 500 banks failed, 16,000 businesses went bankrupt, and there was a 20% unemployment rate in winter again. That left 2.5 million workers without jobs. A few hundred men joined a march on Washington (the first I’ve mentioned) led by a man named Jacob Coxey. Coxey proposed an idea that would eventually be the genesis for the ideas behind the New Deal during the Great Depression. Back in the Panic of 1893, Coxey delivered a petition regarding having road improvement funded by the government as a means of providing jobs to unemployed people. The Congress was frightened, however, of what they called Coxey’s Army and feared revolution. Coxey was jailed and his followers dispersed. He exhibited a rather bizarre face to the world in that he named his son Legal Tender Coxey. Stay tuned, however, for plenty of other marches on Washington.