Confidentiality, but not at all costs

advertisement

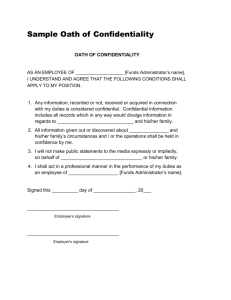

Confidentiality, but not at all costs Supervisors of midwives sometimes need to disclose information about an individual midwife’s practice in order to protect the public, says Kath Mannion Confidentiality is one of the essential elements of midwifery practice and one that every midwife meets on a daily basis – no matter where or what her sphere of practice. As midwives, we regard confidentiality as part and parcel of our job. The same ethos applies to supervisors of midwives and their relationship with the midwives on their caseload. Many would relate confidentiality to how we store and keep information about women. Most women now hold their own notes; we stress that this information is confidential to them, and that if they do not want it revealed to others they must keep the notes in a safe place. However, do we really believe that we keep all information relating to women confidential? Most labour wards have white boards where information relating to each woman present is recorded to a lesser or greater degree. Could this be seen as revealing confidential information, albeit in a controlled area which may only be accessed by staff? The same problems arise within the supervisory relationship. Confidential information may be imparted by the midwife to her supervisor, but how is this kept and might it be revealed at any time? All midwives must have a copy of their annual review, and it is up to the midwife who she discusses this review with. During an investigation into a critical incident, confidential information is gathered by the supervisor of midwives – but to whom may it be revealed? When a midwife is on supervised practice, who knows the details surrounding the decision? Duty rotas reveal, almost like the white board, confidential information relating to a midwife. For example, even though a midwife is written on the rota, the fact that she is supernumerary and working closely with another midwife may signal to others that there may be a problem with her practice. Is there a danger that, by maintaining strict confidentiality among limited numbers of people, repeated incidents might not be linked due to only one or two people knowing the full history? The following information forms the guidance given by the Local Supervising Authorities (LSAs) in England to supervisors of midwives regarding confidentiality within the supervisory relationship, and will hopefully answer the questions posed above. Legislation The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) has set clear guidelines for confidentiality in The Code of Professional Conduct: Standards for Conduct, Performance and Ethics (NMC 2004). Confidentiality of healthcare records is also covered by the Data Protection Act (1998), Caldicott Guardians (NHS Executive 1999), Human Rights Act (1998), NHS Code of Practice (DoH 2003), the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act (1990), Freedom of Information Act (2000) and For the Record: Managing Records in NHS Trusts and Health Authorities (HSC 1999) . Clause 5 of the NMC Code (NMC 2004) states: As a registered nurse or midwife, you must protect confidential information 5.1 You must treat information about patients and clients as confidential and use it only for the purpose for which it was given. (p.8) 5.4 Where there is an issue of child protection, you must act at all times in accordance with national and local policies.(p.9) The code details how confidential information and confidentiality are part of every midwife’s daily working life. The principles within the code apply equally to confidentiality and supervision of midwives. Annual reviews Confidentiality is one of the basics of the supervisory relationship. As such, interaction between the supervisor and midwife may be confidential in full or part, depending on the situation. Disclosure by the midwife to the supervisor may cause a dilemma, especially if the practitioner reveals poor practice which requires remedial action. In facilitating supported or supervised practice, the supervisor is required to maintain a balance between revealing the case to those working with the midwife and keeping details of the midwife’s failings confidential. However, the overriding principle of public protection must be preserved. There is anecdotal evidence that supervisors may have difficulty with confidentiality within the supervisory relationship. Difficulties can arise in determining when confidential information relating to a midwife’s practice must be disclosed. Supervisors have described how, by not sharing confidential information in relation to a midwife’s practice, the supervisory network has been unaware of problems relating to that individual. Several supervisors may have been involved with different issues, but because no one has shared or pooled the information the level of poor practice has not been sufficiently noted and the practitioner appropriately supported. Public safety may also be compromised in this instance when each supervisor has seen the incident or poor practice as a ‘one-off’ and has not had the opportunity to see the full picture. The lessons from the Laming Report (Lord Laming 2003) into the death of Victoria Climbie can equally be applied to supervision. The report found that information silos relating to her case were held by different professionals but there was no overview or sharing of the information. It may be necessary to reveal confidential information to other professionals to ensure proper support for the midwife and public safety. Midwives may reveal to their colleagues some if not all of the facts relating to them. The midwife’s account of her story may be told differently once it has been related to other colleagues. The supervisor may hear a very different story via the informal networks. On no account should the supervisor be tempted to correct details since this is also a breach of confidentiality. Supervisory records Supervisory records must be kept separate from employment/personal records. Guidance on storage of supervisory records is available to all supervisors of midwives and midwives from the LSA Midwifery Officers. The Midwives’ Rules and Standards (NMC 2004) state, in Rule 12: Although these records are confidential between you and your supervisor it is important for you to understand that in certain circumstances they may be disclosed, for example, in a local supervising authority or NMC fitness to practice investigation. In other circumstances, a court order would be required before the disclosure of these records. (p.27-28) Disclosure of information regarding a particular midwife should be on a ‘need-to-know’ basis, and the supervisor must ensure that the midwife understands the concept of confidentiality within supervision. Supervisors of midwives must share issues both for personal support and to achieve professionally optimum outcomes. It is also important to utilise issues as learning experiences and for supervisors to learn from them while maintaining confidentiality within the supervisory framework. Clearly, the midwife must also be made aware that the LSA Midwifery Officer and/or the NMC may also need to be made aware of the information. Discussion Many midwives and supervisors will relate to the above guidelines and have found that confidentiality within the supervisory relationship is maintained even when a serious incident is being investigated. Supervisors must focus on the balance between maintaining confidentiality and protection of the public – not an easy task. Confidential information relating to annual supervisory reviews or investigations may be revealed by the midwife to her friends and colleagues. The midwife needs to be aware that this information is confidential to her, and that by revealing it to others there is a risk that it might be spread among other members of staff to whom she might not wish to impart this information. Supervisors report frustration when they overhear other midwives discussing a case where the information has become skewed, and they are unable to correct this because it would breach confidentiality in relation to the individuals concerned. When dealing with women receiving midwifery care, confidential information may need to be revealed because of overriding concerns – for example, child protection issues. Similarly, issues relating to an individual midwife’s practice may need to be revealed in order to protect the public. Both cases require sensitive handling to achieve the best outcome, and it is essential that supervisors of midwives work alongside their colleagues and discuss the issues in a safe, confidential environment. Advice and guidance can also be sought from the LSA Midwifery Officers. TPM Kath Mannion is Local Supervising Authority Midwifery Officer, Northern Consortium of Local Supervising Authorities. A full listing of contact details for LSA Midwifery Officers in England is available at www.nmc-uk.org References Data Protection Act (1998). London: HMSO. DoH (2003). NHS Code of Practice, London: Department of Health. Freedom of Information Act (2000). London: HMSO. HSC 199/053 (1999). For the Record: Managing Records in NHS Trusts and Health Authorities, London: Public Records Office. Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act (1990). London: HMSO. Human Rights Act (1998). London: HMSO. Lord Laming (2003). The Victoria Climbie Inquiry: the Report of an Inquiry by Lord Laming, London: HMSO. NHS Executive (1999). Protecting and Using Patient Information: a Manual for Caldicott Guardians, London: NHS Executive. NMC (2004). The Code of Professional Conduct: Standards for Conduct, Performance and Ethics, London: NMC. NMC (2004). Midwives’ Rules and Standards, London: NMC.