Chapter 1 Getting Started This chapter covers the need for filing

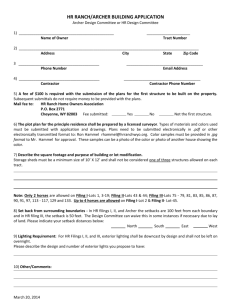

advertisement