Unit One (pp 18-21) Language Of Literature The Anglo

advertisement

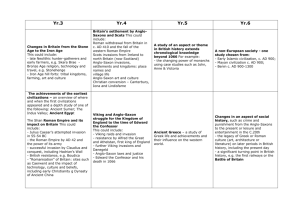

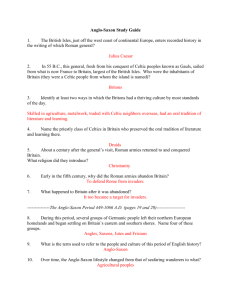

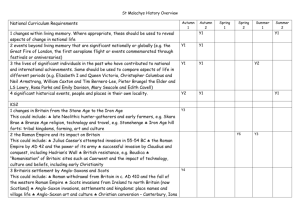

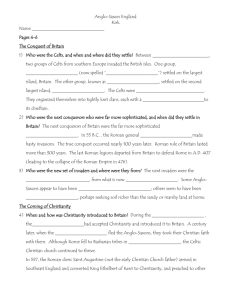

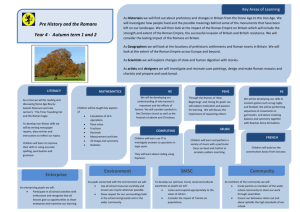

Unit One (pp 18-21) Language Of Literature The Anglo-Saxon Period, 449–1066 The British Isles, just off the west coast of continental Europe, enter recorded history in the writings of the Roman general Julius Caesar. In 55 B.C., fresh from his conquest of Celtic peoples known as Gauls, Caesar sailed from what is now France to Britain, largest of the British Isles, to assert Rome's authority over it. There he encountered a Celtic people called the Britons, from whom the island takes its name. Also living on Britain were Picts, remnants of a pre-Celtic civilization, and farther west, on Ireland (the next-largest British island) was another group of Celtic speakers, the Gaels. The Britons had a thriving culture by most standards of the day. They were skilled in agriculture and metalwork, traded with their Celtic neighbors overseas, and had an oral tradition of literature and learning preserved by a priestly class known as druids. They were, however, no match for the Romans. About a century after Caesar's visit, Roman armies returned to Britain to make good his claim. Despite resistance, they rapidly conquered the Britons and drove the warlike Illustration by John Sandford. Picts northward to what is now Scotland. Britain became a province of the great Roman Empire, and the Romans introduced cities, fine stone roads, written scholarship, and eventually Christianity to the island. As they adapted to a more urban way of life, the "Romanized" Britons came to depend on the Roman military for protection; but early in the fifth century, with much of their empire being overrun by invaders, the Roman armies abandoned Britain to defend the city of Rome. It was not long before Britain too became the target of invasion. The Anglo-Saxon Period, 449-1066 In an invasion traditionally assigned to the year A.D. 449 but actually taking place over several decades, Angles, Saxons, and other Germanic peoples (such as Jutes and Frisians) left their northern European homelands and began settling on Britain's eastern and southern shores. The Britons—perhaps led by a Christian commander named Arthur—fought a series of legendary battles in an effort to stop the invasion. Eventually, however, they were driven to seek refuge in Cornwall and Wales on the western fringes of the island; in the northern area now called Scotland, where Gaels from Ireland were also settling; and in an area on the west coast of continental Europe that would come to be known as Britanny. In southern and central Britain, Celtic culture all but disappeared. The Germanic tribes eventually organized themselves into a confederation of seven kingdoms called the Heptarchy. In the southeast was Kent, kingdom of the Jutes. Further west were the Saxon kingdoms of Sussex, Essex, and Wessex. To the north were the kingdoms of the Angles—East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria. Perhaps because the Angles were dominant in the early history of the Heptarchy, the area of Germanic settlement became known as Angle-land, or England, and its people came to be called the English. Modern scholars, however, usually employ the term Anglo-Saxon to refer to the people and culture of this period of English history. Like all cultures, that of the Anglo-Saxons changed over time. The early invaders were seafaring wanderers whose lives were bleak, violent, and short. With them, they brought their pagan religion— marked by a strong belief in wyrd, or fate—and their admiration for heroic warriors whose wyrd it was to prevail in battle. As they settled into their new land, however, the Anglo-Saxons became an agricultural people—less violent, more secure, more civilized. One of the most important civilizing forces was the Christianity they began accepting late in the sixth century. The Growth of Christianity Despite the collapse of Roman power there, Christianity had never completely died out in the British Isles. Early in the fifth century a Romanized Briton named Patrick had converted Ireland's Gaels to Christianity. When the Gaels began colonizing Scotland, they brought Christianity in their wake. From the isle of Iona off the Scottish coast, missionaries spread the faith among the Picts and Angles in the north. Later, in 597, a Roman missionary named Augustine arrived in the kingdom of Kent, where he established a monastery at Canterbury. From there, Christianity spread so rapidly that by 690 all of Britain was at least nominally Christian. The Danish Invasions In the 790s, a new group of northern European invaders—the Danes, also known as the Vikings— began to devastate Northumbria's flourishing culture. Coming at first to loot monasteries, the Danes in time gained control of much of northern and eastern England. They were less successful in the south, where their advance was halted by a powerful king of Wessex, Alfred the Great. After inflicting defeats on the Danes in 878 and 886, Alfred forced them to agree to a truce and to accept Christianity. Although Alfred's reign was a high point in Anglo-Saxon civilization, the tug-of-war with the Danes resumed after his death. In 1016 a Dane named Canute even managed to become king of all England; he proved a successful ruler and won the support of many Anglo-Saxon noblemen. Less successful was the deeply religious Edward the Confessor, who came to the throne in 1042. Edward, who had no children, had once sworn an oath making William, duke of Normandy, his heir—or so William claimed. Later, Edward was persuaded to name Harold, earl of Wessex, as his heir. When Edward died in 1066, the English witan (an advisory council of nobles and church officials) supported Harold's claim. Incensed, William led his Normans in what was to be the last successful invasion of the island of Britain: the Norman Conquest. Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings, and on Christmas Day of 1066, a triumphant William—who would go down in history as William the Conqueror—was crowned king of England. Literary History The spread of Christianity in Britain was accompanied by a spread of literacy and by the introduction of the Roman alphabet in place of the runic alphabet. Though poetry remained primarily an oral art, poems were now more likely to get written down. In this age before printing, however, the only books were manuscripts that scribes copied by hand. Thus, only a fraction of Anglo-Saxon poetry has survived, in manuscripts produced centuries after the poems were composed. The most famous survivor is the epic Beowulf about a legendary hero of the northern European past. A manuscript known as the Exeter Book contains many of the surviving Anglo-Saxon lyrics, including "The Seafarer," "The Wife's Lament," and over 90 riddles. Most Old English poems are anonymous. One of the few poets known by name is a monk called Caedmon, described by the Venerable Bede in his famous eighth-century history of England. Like most scholars of his day, Bede wrote in Latin, the language of the church. It was not until the reign of Alfred the Great that writing in English began to be widespread. In 891, Alfred initiated the compiling of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a historic record in poetry and prose that was added to, on and off, until early Norman times. He also encouraged English translations of portions of the Bible and other Latin works.