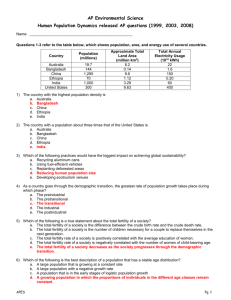

Population Policy in the Philippines, 1969-2002

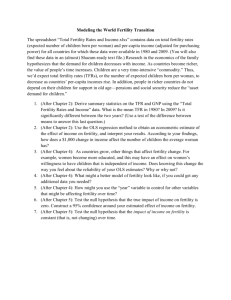

advertisement