Report on being a Research Assistant in Madagascar with The

advertisement

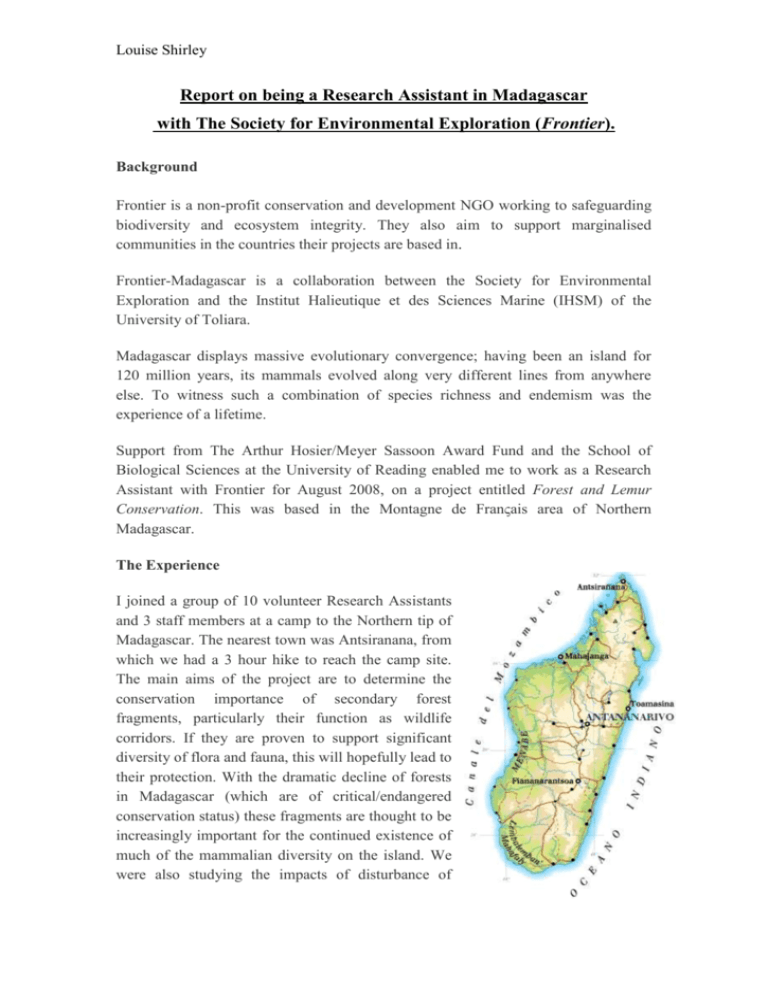

Louise Shirley Report on being a Research Assistant in Madagascar with The Society for Environmental Exploration (Frontier). Background Frontier is a non-profit conservation and development NGO working to safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystem integrity. They also aim to support marginalised communities in the countries their projects are based in. Frontier-Madagascar is a collaboration between the Society for Environmental Exploration and the Institut Halieutique et des Sciences Marine (IHSM) of the University of Toliara. Madagascar displays massive evolutionary convergence; having been an island for 120 million years, its mammals evolved along very different lines from anywhere else. To witness such a combination of species richness and endemism was the experience of a lifetime. Support from The Arthur Hosier/Meyer Sassoon Award Fund and the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Reading enabled me to work as a Research Assistant with Frontier for August 2008, on a project entitled Forest and Lemur Conservation. This was based in the Montagne de Franςais area of Northern Madagascar. The Experience I joined a group of 10 volunteer Research Assistants and 3 staff members at a camp to the Northern tip of Madagascar. The nearest town was Antsiranana, from which we had a 3 hour hike to reach the camp site. The main aims of the project are to determine the conservation importance of secondary forest fragments, particularly their function as wildlife corridors. If they are proven to support significant diversity of flora and fauna, this will hopefully lead to their protection. With the dramatic decline of forests in Madagascar (which are of critical/endangered conservation status) these fragments are thought to be increasingly important for the continued existence of much of the mammalian diversity on the island. We were also studying the impacts of disturbance of Louise Shirley different species. Each day we conducted abundance and distribution surveys in the surrounding forest using a range of techniques. We mapped vegetation, disturbance and resource-use in the area. We also set pitfall and Sherman traps, did sweep-netting for butterflies and dragonflies, bat monitoring, bird watches, active searches (usually at night) for amphibians and reptiles, and measured and recorded everything we found to form a comprehensive database. I had limited knowledge of herpetology, so this was an invaluable opportunity to gain experience. This was supported by a collection of science journals and specialist reference books which were very useful for identification. I found Melantis ledahelena, a species of butterfly which had never been recorded in the area before. We also studied mammal populations. Malagasy native land animals are predominately forest dwellers. Lemurs lived beside our camp and most nights I went to sleep, under a blanket of stars, to the sound of them grunting above my hammock. They tend to be very primitive animals but one night, a lemur climbed down one of the jackfruit trees until he reached head height, two meters away from me. We stared at each other for a long time. It was very moving, and absolutely unforgettable. We were also involved with the nearest village and explained our work to them. We learnt some Malagasy and I taught a few lessons at the school, covering subjects such as food chains and forest ecology. The children and many of the adults were surprised to hear that lemurs are endemic to Madagascar. I now appreciate our education system- in England it’s a right, and it tends to be taken for granted. In Madagascar it’s very different; the school had one teacher, and no books, but the children seemed to appreciate their classes. We also held ‘Environment Day’, a fête in their schoolyard to raise awareness of various environmental issues. The entire village was invited. We made posters, games, a model to demonstrate the water cycle, and others to Louise Shirley communicate the impacts of overpopulation, river pollution and deforestation. We also built the village beehives so that they can produce, and hopefully sell, their own honey. I spoke to students of Diego University, who told me about their culture and beliefs which was very interesting. Camp life was very basic; we baked bread for breakfast and ate rice and beans for lunch and dinner every day. We collected drinking water from a local stream. This experience has lent me a more realistic view of several conservation issues. Deforestation is a massive problem in Madagascar, which I witness first-hand. An area we had been studying one day had been cleared by the time we re-visited it the following week. Flying over the country, the landscape looked incredibly barren. It looked like African plains, but without the wildlife. Only 10% of original forest cover remains and it was a haunting sight (see photo below); I also saw the great quantity of wood required to sustain a family. Seeing all of these things has made me appreciate the complexity of the issues conservationists face. Overpopulation is a root problem, but one that is very difficult to address. Working in Madagascar has confirmed for me that I want to work in conservation. I also feel that it has made me a more focused and observant person. I have come away with many practical skills and a deeper understanding I would not otherwise have had. It has also made me truly appreciate the standard of living and education in England. Closing comments Louise Shirley I would like to express deep gratitude to the Selection Committee for awarding me the Arthur Hosier/Meyer Sassoon Award, without which my trip would not have been possible. I also really appreciate the support from The School of Biological Sciences, specifically Professor Nick Battey and Dr. Mark Fellowes. Madagascar has the greatest number of critically endangered primates of any country in the World, and to have an opportunity to join the effort to protect them was a great honour. My time there altered my perspective on life, and my future career plans, dramatically.