Part One: Fundamental Concepts of Landlord

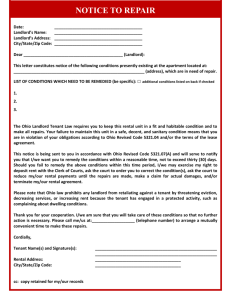

advertisement